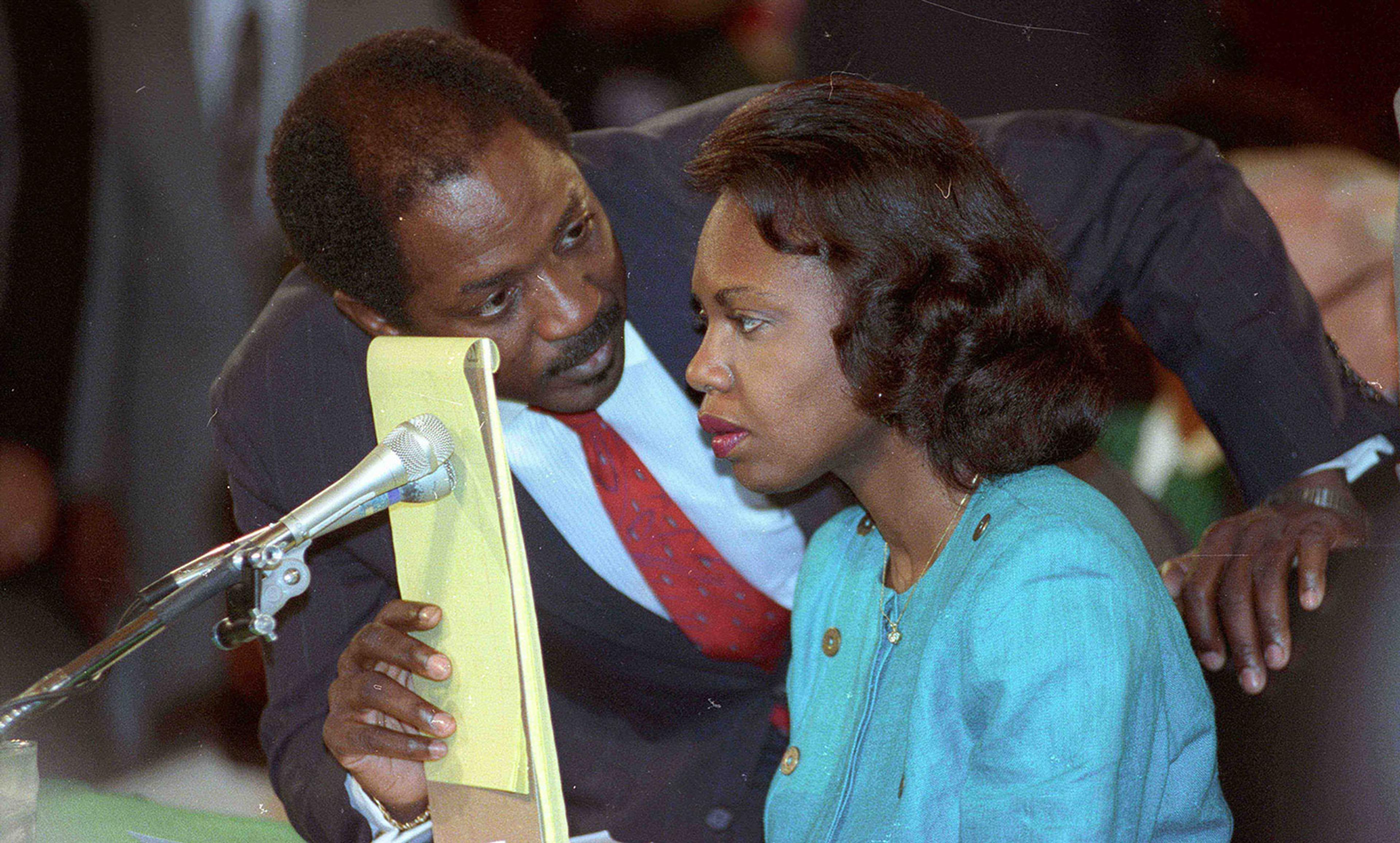

Counsel Charles Ogletree advises the law professor Anita Hill during her testimony on 11 October 1991. Photo by Rick Wilking/Reuters

As decades-old sexual assault allegations increase, so does the question: why didn’t women report it sooner? Shame, fear of reprisals and the unfortunately common belief that they are responsible for provoking the offender are just a few of the many reasons why women choose not to report a threat, harassment or assault.

Of course, individual women will have their own unique reasons but, as a group, Black women are the least likely to report. Surveys point in part to cultural reasons, ranging from pressure to protect Black men to not putting personal business in the street. Notably, however, Black women also say that they don’t think anything good will result from reporting. What we are or aren’t able to imagine after we’ve been victimised matters because the action we take will be the one that we can imagine bringing the desired outcome – and if we can’t imagine it, we won’t act on it. Black women don’t report at the same rates as other women because Black women can’t imagine being treated justly.

The 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume said that ‘nothing is more free’ than the human imagination. Perhaps. But for some of us, imagination is overwhelmed by dehumanising experience. As a result, we are paralysed, and the kind of imagining involved in taking action is undermined. The range of imaginable outcomes directly impacts the range of possible courses of action that the imagination presents to the mind. Depending on what we imagine as an outcome, we might decide to alert the authorities – or, alternatively, we might decide not to tell anyone, let alone the authorities. What we imagine as a desirable, realistic outcome will guide us to the action that we imagine will bring it about. What we imagine will depend on what we’ve experienced, and if we can’t imagine an action bringing about the desired outcome, we won’t take that action.

As a Black woman, I hold affirming beliefs about myself balanced against the reality that society doesn’t share them. This is what the sociologist W E B Du Bois in 1903 called double consciousness – seeing myself in one way, while simultaneously aware that oppressive society sees me in another – and it truncates the faculty of imagination. It takes the mind on a wild, dizzying ride that dead-ends in a paltry selection of actions to bring a desirable outcome. Black women navigate life doubly, even triply conscious at the intersections of gender, race and sexuality, polluted with traffic and noise. Our situation is unique.

This September, Christine Blasey Ford gave her testimony of sexual assault before Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the US Supreme Court. Writing an op-ed in The New York Times in response, the legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw reflected on lessons still unlearned since Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas before his own Supreme Court nomination in 1991: ‘We are still ignoring the unique vulnerability of black women.’ Those of us who are, like Hill, multiply marginalised have to contend with the power of intersecting negative outcomes from everywhere – including ‘our people’. Sandwiched between antiracist groups who sided with Thomas and ignored Hill’s gender, and feminist groups who ignored her race, Hill was subsequently split in two – with neither group caring about the wellbeing of the woman they were busy cleaving. Under these continuing circumstances, what Black woman readily imagines being taken seriously, being seen as someone worthy of protection, and receiving justice as a realistic outcome?

In those brief moments between a harassment, assault or threat, and imagining what to do, our imagination presents us with an array of possible actions we can take. Those precious moments are crucial to our wellbeing. If our imagination is full of the ugly ways that the authorities interact with people like us, if it is cluttered with the doubt and distrust we know we are likely to face from people who don’t know us (and some who do), we might be unable even to conceive of doing anything more than disclosing to a person we trust, let alone turning to an authority.

In 2015, I received a letter via snail mail from a man who – credibly – threatened to come to the campus where I work and ‘teach me a lesson’. He was enraged by an op-ed I wrote for The Washington Post after I visited Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Virginia. In the article, I wrote that, during my tour, many white visitors chose to visit only the house, bypassing the slave quarters. I said that it shouldn’t be an option to avoid confronting something so critical to US history, given that slavery’s legacy continues to this day. I received more than 700 online comments. Of the comments I read, most were nasty, ad hominem attacks on my gender, race and sexual orientation. To them, I wrote a response. I didn’t know what to do about the threatening letter.

Someone unlike me in the ways that matter would have immediately contacted campus security, but that never occurred to me. I couldn’t imagine that I would be seen as someone worth protecting. I also did not imagine calling the police when I was the victim of an attempted sexual assault at the age of 19. I didn’t consider reporting it – it simply never came to mind.

My life matters to me, but I’m aware that it doesn’t matter – or doesn’t matter much – to many others, precisely because it is a black life. There wouldn’t be a Black Lives Matter movement if this were not so. Expecting Black women who have been harassed, sexually assaulted or threatened to report it is asking them to do something Herculean: override an overwhelming number of experiences in which they have been doubted, disbelieved, ignored, treated unjustly by the police, and told to keep silent to protect ‘our’ men by people we trust. Black women are squarely in a vortex of contradiction, leaving our imagination blunted – and a void where justice should be.

Ironically, while our imaginations fail, the privileged ones’ imaginations are impoverished. The ones who navigate the world virtually free from the experience of repeatedly being doubted and disbelieved, the ones whose experience with denial is to refuse it, will be unable to imagine what it is like to be us, or to have to search through a sea of negative outcomes to locate a couple of positive ones – if our imaginations let us – that we then often discard. They will refuse to try to imagine what it is like to be the prey of predatory men in a racist rape culture.

Let us hope that as more women disclose, report and pursue justice, our collective imagination will coax justice out of fantasy and into reality. As for me, I was lucky that nothing came of that threat. I was lucky that the sexual assault wasn’t ‘completed’. And it’s a good thing, too, because I can only imagine what would have happened if it had.