Fibonacci Blue/Flickr

Like many native white Southerners, I have ancestors who owned slaves and fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. I first learned about my ancestors from my maternal grandparents, whom I idolised. Although they died 20 years ago, I still sometimes have the urge to pick up the phone and call them. I carry their house key and I talk to my children about them. It is sometimes hard to distinguish between my love for them, my yearning to honour their memory, and how I think about the South. I love the South and much of its history because I associate it with my family, to whom of course I will always be devoted.

Still, I regret – even feel ashamed – that many of my ancestors were slave-owners. One of them was even a leading pro-slavery legal scholar, who, in 1858, wrote one of the most important pro-slavery treatises.

If you had asked me about Confederate monuments five years ago, I would have argued for the display of Confederate symbols partly on the basis of Proverbs 22.28: ‘Do not move the ancient landmark that your fathers have set.’

I have come to see the issue differently. Two things have changed my mind. First, I’ve spent time reading Frederick Douglass, W E B Du Bois, Carter Woodson and other African-American writers; and I’ve built relationships with scholars of African-American history such as Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Edward Carson, Keisha Blain and others in the African American Intellectual History Society. Second, I began to see the issue as a matter of Christian freedom and neighbour-love. For example, Christ said in Matthew 7:12: ‘In everything, therefore, treat people the same way you want them to treat you, for this is the Law and the Prophets.’

In my former home in Charlottesville in Virginia, there stands an equestrian statue of the Confederate general Robert E Lee. It’s stood in the city square since 1924 and it is impressive. Lee Park, where it stands, is beautiful. Recently, a 15-year-old Charlottesville High School student started a petition to have the statue removed. The city council took up the issue and will decide on it soon. Predictably, the question of what to do with the statue of Lee is enormously controversial.

As a Southerner and a Christian, I am left to ask – who exactly is requesting that the statue be removed? Are they outsiders? Or are they full-fledged members of the community? In other words, are the signers of the petition Virginians? Charlottesvillians? Neighbours?

If they are fully vested in the community, then those who disagree should take them seriously.

Consider a historical parallel. During the 1770s and 1780s, American patriots removed statues of King George III. They did so because they objected to what he symbolised. At the very least, he no longer served as a unifying symbol. Not everyone wanted to remove the statues. The situation in Charlottesville now is not a perfect analogy, of course. But it demonstrates that black people who want to see Lee’s statue removed have a legitimate basis for their argument.

Advocates for keeping Lee’s statue often say that taking it down would be ‘removing history’ or ‘re-writing history’. But the statue is not history, nor does it teach history. To think historically, it is necessary to think about the country and Charlottesville in 1924, when the statue was erected. Back then, Lee and the Civil War signified very different things to most Americans than they do today. In the 1920s, Lost Cause and Dunning School historiography advanced the idea that secession was noble, that slavery was benevolent, and that Reconstruction demonstrated the inferiority of black people. Those attitudes are no longer acceptable.

Many of my friends want to keep the statue of Lee. First, I say to them, I am one of you. My Confederate heritage credentials are unimpeachable. My great-great-great grandfather was Thomas R R Cobb, member of the Confederate Constitutional drafting committee; veteran of the battles of Seven Days, Second Manassas, and Antietam; brigadier general under Longstreet at Fredericksburg where he was killed in action after hurling back the main Federal assault six times from the Sunken Road. My great-great-great uncle Howell Cobb was president of the Provisional Confederate Congress and as a Confederate major general was overall commander of Georgia state troops.

Second, we who love our Southern heritage need to honestly reflect on the impact our ancestors’ actions had on black people. We must ask, why does the pain of slavery endure after all these years? What would we think about Confederate memorials if seven-eighths of our time on this continent since 1619 was defined by slavery and state-sponsored apartheid? Do we value the past (or ‘heritage’) more than black people?

If black people are Americans, does it not make sense that those Americans would recoil from commemorating the enemy of their country?

We who have emotional attachments to the Southern Confederacy can honour our ancestors’ memory without continuing to ignore and marginalise the historical experiences of fellow citizens who are African American. We can honour our ancestors’ memories, remembering that they were not gods, but sinful men and women. In honouring them, we must apply honesty and humility when we remember the meaning of their lives’ work, work that was not always performed for the flourishing of all people. I know that my grandparents would not want me to deify them, but to remember them with honesty. I like to think that my 19th-century ancestors would want the same.

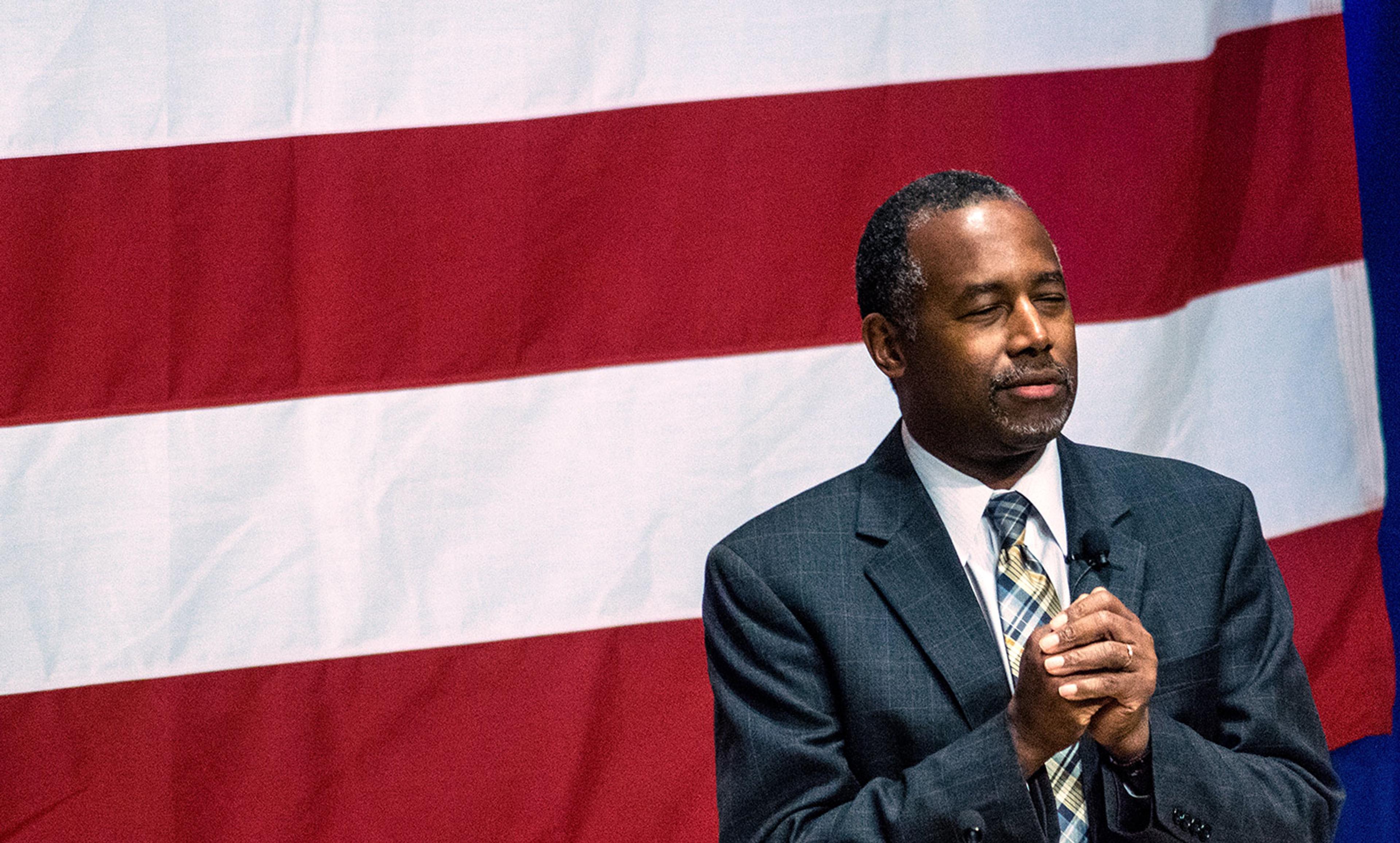

A fellow conservative recently accused me of being politically correct because I said that there are valuable aspects to the Black Lives Matter movement. Well, whatever the movement represents, the key issue seems to be the human personhood of black people. The statement ‘black lives matter’ is pregnant with meaning given that US society in general has not historically taken it seriously.

It is tragic that African Americans often think they must make the statement at all. It is also sad that more Christians do not rise up in solidarity with black folks who see its necessity.

Count me in as a white Southern conservative Christian who stands in solidarity with African Americans. Black lives matter.