‘If you’re running for president as a Republican, chances are good that you are wearing cowboy boots,’ noted Ryan Teague Beckwith in a photo essay published by Time magazine in 2015. Beckwith’s assertion came with receipts: photographs showing cowboy-booted Republicans from nearly every corner of the nation, from Sarah Palin of Alaska, to Tim Pawlenty of Minnesota, to Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, to Mike Huckabee of Arkansas, to Rick Perry and Ted Cruz of Texas. Wearing cowboy boots, it seems, signals Republican fealty to an ostensibly traditional, more conservative United States.

The cowboy boot fetish, suggested Beckwith, began with Ronald Reagan, the hobby rancher, cowboy actor, and US president from 1981-89. Reagan, however, was a latecomer. The prototype for the cowboy conservative was Barry Goldwater, the senator from Arizona, who won the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1964. Goldwater joined West and South against the moderate, ‘Eastern establishment’, Rockefeller wing of the Republican Party, creating what the California governor Pat Brown called ‘the stench of fascism’. In her recent book How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America (2020) – currently, Amazon’s top seller in the political history category – the historian Heather Cox Richardson expands and modifies Brown’s observation, arguing that Goldwater’s ‘Movement Conservatism’ – meaning vehement opposition to civil rights bills, communism, labour unions and social spending – solidified a neo-Confederate alliance between West and South that permanently transformed the Republican Party.

In Richardson’s telling, the Reagan/Goldwater cowboy persona evolved out of literary myths manufactured in the late 19th century specifically to counter Reconstruction era racial reforms, myths that 20th-century reactionaries used in their battle against civil rights. The anti-civil rights, anti-government alliance between South and West that began in the late 19th century, she argues, continued with early 20th-century opposition to anti-lynching bills before spawning Movement Conservatism in the 1960s.

What I’d like to offer here is a counter-history. To the degree that progressives formed successful constituencies in the 20th century – in economic, gender, racial and even foreign policy matters – the West was key. What I’ll further argue is that the Western ‘cowboy myth’ often lent support to progressive politics. Contrary to what many modern progressives imagine, the conservative monopoly on the cowboy myth is as much a commentary on the Democratic Party’s drift toward a ‘professional middle-class’ constituency as it is a commentary on Republican reaction.

To make those arguments, let me begin with some family memoir. I was born in Arizona, where I lived, at different times, with my Republican maternal grandmother in suburban Tucson and with my paternal grandparents – both Democrats – in the heart of Phoenix. Their very different experiences and politics offer a window into how and why the inland West often tilted in progressive directions in the first half of the 20th century, then tilted conservative in the second half.

My paternal grandparents – the Phoenix grandparents – had come from Arkansas in the 1920s as part of a larger movement from a region extending to Oklahoma and Texas where economic decline preceded the Great Depression. A short time after arriving in Arizona, they enrolled in the final election campaign of one George W P Hunt, who had already served seven two-year terms (having first been elected in 1911, the year before Arizona became a state).

Though a Democrat, Hunt was heir to a Western tradition of populism that resonated into the 20th century. In concert with Arizona’s powerful labour movement, Hunt helped write the ‘People’s Constitution’, which barred corporations from blacklisting strikers, funding political campaigns, and employing armed bodies of men. He also favoured women’s suffrage (which Arizona passed by initiative in 1912) and lobbied for the abolition of capital punishment (yielding another successful initiative in 1916, though voters overturned it a few years later). He went so far as to spend nights in the penitentiary to understand what prisoners experienced.

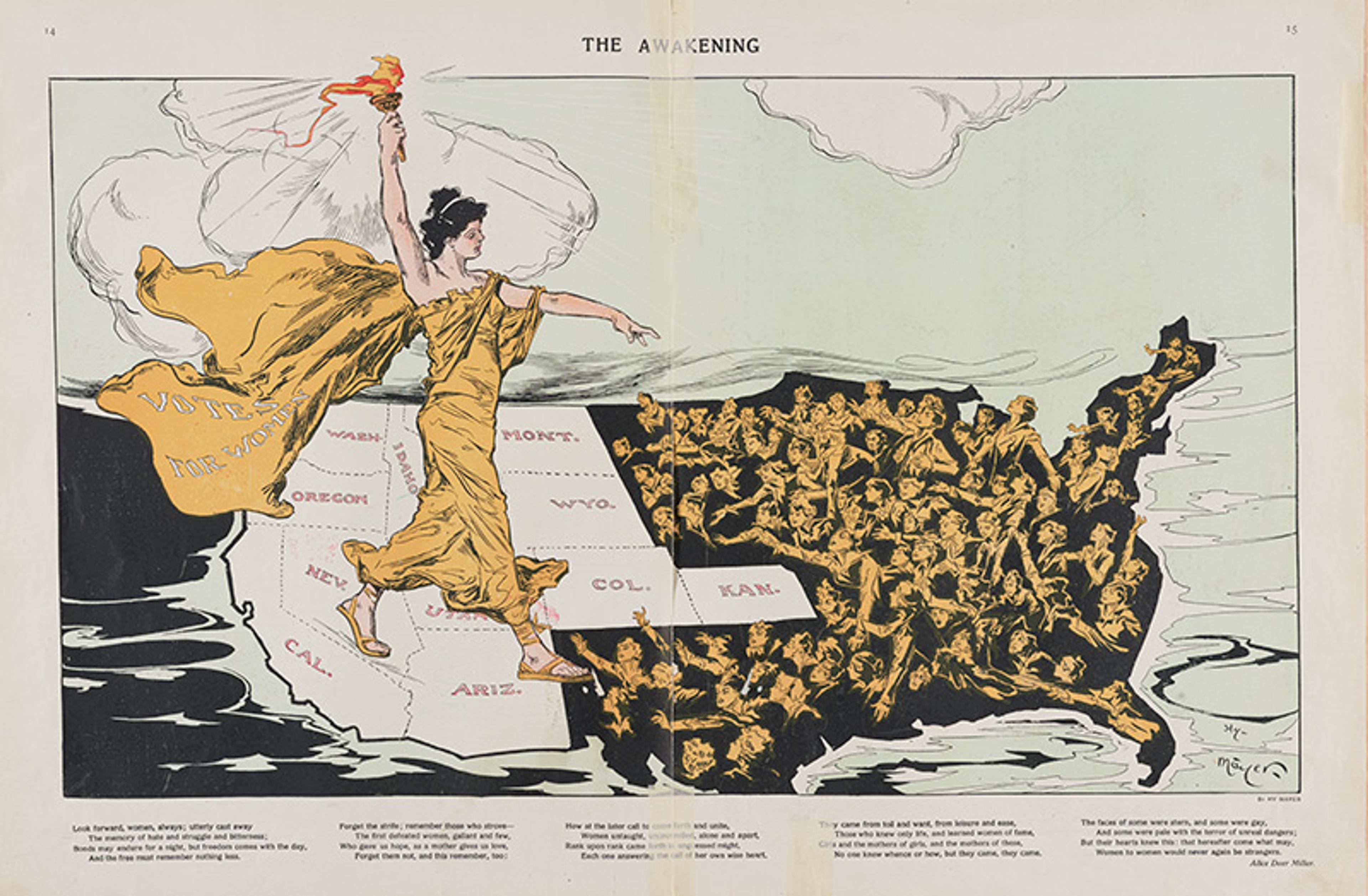

The Awakening (1915), by Henry Mayer. Women of the eastern states reach out towards a torch bearer from the West where states had already granted women the right to vote. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Hunt was the sort of politician whom we might call an ‘economic progressive’, a sort of early 20th-century incarnation of Bernie Sanders. Hunt’s politics, however, could be decidedly racist. During the framing of the state’s ‘People’s Constitution’, for example, he voted to segregate the state’s schools (that particular provision failed, but the constitution nonetheless allowed local and state authorities to enact subsequent segregation statutes, which they did). Hunt also refused to oppose the initiative that created Arizona’s ‘80 per cent law’ – mandating that any given company’s workforce had to comprise at least 80 per cent native-born or naturalised Americans – and supported a literacy test intended to deter Mexican Americans from voting.

11 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, Arizona Democrats put civil rights on their political map

It would be a mistake, however, to view Hunt’s politics as invariably racist. In 1915, he vehemently opposed the death sentences meted out to four Mexican citizens and a Mexican American. With the help of the secretary of state William Jennings Bryan, Hunt prevailed on the parole board to grant clemency. A year later, he risked his political career by actively supporting Mexican American miners in a bitter copper strike.

It might be too much to suggest that the Democratic jackass of Hunt’s day was moving – haltingly and grudgingly, as jackasses are wont to do – toward ‘racial progressivism’. If that was the route that Arizona Democrats were taking, they showed little actual progress for another 30 years. By the 1940s, however – thanks to the labour movement’s increasing support for civil rights, the influence of Mexican American voters, and the larger renunciation of Hitlerian racial hierarchies – Arizona Democrats began to combine a vision of racial inclusion with their longstanding economic progressivism.

Hunt lost the 1934 gubernatorial election and died soon after. My grandfather, just 26 that year, subsequently rose through the ranks of the county and state highway departments, becoming shop superintendent and later director of the state highway department. He also became a political ally and friend of Sidney P Osborn, Arizona’s popular Second World War-era governor. Osborn’s constituency, like Hunt’s, consisted of organised labour along with ranchers, farmers, and women. In 1944, he convened his core supporters in the ‘Arizona Labor Victory Committee’ (ALVC) – a committee comprised of union leaders, women’s groups, and delegates from ‘minority’ groups – in order to hammer out a progressive platform, including a plan to desegregate schools. Though Osborn made no public comment on the ALVC’s desegregation plan, my 94-year-old father recalls that Osborn’s wife, Gladys, gave talks to women’s groups in support of it. Though Osborn’s enemies widely circulated a flier decrying him as an integrationist, he carried every county in the 1944 election.

Three years before Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier in baseball, four years before President Harry Truman desegregated the US Army, 10 years before the Brown vs Board of Education decision, and 11 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, Arizona Democrats put civil rights on their political map. Osborn, to be sure, didn’t press forward on the racial front, but other Democrats did.

In 1948, Mexican American leaders and white progressives joined forces in Alianza Hispano-Americana and the Arizona Council for Civic Unity. Though their antisegregation initiative failed in 1950, they subsequently won several state court cases that abolished segregation in schools and public facilities. The court cases weren’t Arizona’s only civil rights successes. In 1955, the Democratic governor Ernest McFarland signed into law the Equal Public Employment Opportunities Act, which barred discrimination in state hiring. McFarland was also the first Arizona governor to hire a Black secretary.

None of this suggests that white Democrats of my grandfather’s day were civil rights warriors. It does suggest that Arizona wasn’t an extension of the Deep South, where Democratic governors ferociously opposed desegregation. Even as Democrats formed cross-racial constituencies, however, other political forces pushed in conservative directions, leading to the election of Goldwater to the Senate in 1952.

To understand why Arizona (along with the Mountain West as a whole) trended Republican in the second half of the 20th century, that 1952 Senate election – wherein Goldwater ran against McFarland (the same man who would later serve as governor) – is key. Neither McFarland, a two-term New Dealer and ‘father of the GI Bill’, nor Goldwater, a one-term Phoenix city council member, played the cowboy, though both benefited to a limited degree from the ‘myth of the West’. Gene Autry, the world’s foremost cowboy singer, appeared for McFarland. Goldwater, meanwhile, had gained notoriety from his photography of Arizona peoples and places, his documentary video of running the Colorado River, and his experience as a fighter pilot. Goldwater also got help from Dwight Eisenhower and Joseph McCarthy – author of the anti-communist hysteria known as McCarthyism – who visited the state on his behalf.

The returns tell a fascinating story. McFarland remained popular among older, rural voters, workers and ‘pinto Democrats’ – farmers and ranchers – who gave him majorities in nine of 12 rural counties. Goldwater, however, prevailed in both of the urban counties (Maricopa, home to Phoenix, and Pima, home to Tucson). His 17,056-vote majority in the urban counties exceeded McFarland’s 10,331-vote rural majority, allowing Goldwater to eke out a victory.

Ruralites tilted Rightward because urban business elites increasingly set Arizona’s economic tempo

When McFarland examined the election data, he found that ‘it was not the people who knew me that had caused me to lose, but the new people who had come into the state.’ Since the Second World War, prosperous newcomers – most of them from the Midwest – had flooded Phoenix and Tucson, bringing their Republican politics. Though progressive Democrats (including McFarland) still won state-wide elections now and again in the 1950s and ’60s, they no longer dominated the state. Like Atlantis of old, ‘labour Arizona’ disappeared beneath the seas.

All that may seem straightforward enough, and yet it also suggests a mystery. Modern progressives tend to do well in urban areas, whereas modern conservatives perform best in rural areas (at least those with white-majority populations). The pattern is ubiquitous in the US, no matter the region (with suburban districts acting as swing voters). In 1950s Arizona, however – and elsewhere in the Mountain West – progressive Democrats did well in rural areas, partly due to their historic support for Social Security, reclamation, electrification and the GI Bill. Rural Westerners weren’t outspoken racial progressives, but they often proved willing to vote for candidates who supported civil rights legislation, so long as that candidate served their economic interests.

That’s not to say that those rural voters were yellow dog Democrats (so called because they would vote for a yellow dog if one ran as a Democrat). Even in the 1952 McFarland-Goldwater election, rural voters had begun tilting Rightward, though not necessarily because of Democrats’ support for civil rights (which wasn’t an election issue), and much less because of later culture war issues such as abortion and guns. Ruralites tilted Rightward – slightly – because urban business elites increasingly set Arizona’s economic tempo. Yes, Arizona had thrived due to government spending – particularly on defence, highways and reclamation – but that very success empowered conservative power brokers, particularly those in the Valley National Bank, author of tens of thousands of Arizona home loans, and the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce.

Thus the pro-labour, pro-civil rights Democratic West of my Phoenix grandparents became the anti-labour, anti-civil rights Republican West of my Tucson grandmother, who had made her fortune in the construction business in Kansas City before retiring to Arizona. The same sort of demographic and political shift occurred throughout the Mountain West in the postwar decades, though the change was neither seamless nor immediate. Indeed, the Mountain West states elected influential progressive US senators into the 1980s.

To get a fuller understanding the Mountain West’s political trajectory – and how the cowboy myth could sustain a progressive vision – we would do well to examine a tall tale of a man named Glen Taylor, son of a Texas Ranger turned hellfire evangelist who had homesteaded in Idaho in the early 20th century. Taylor – who, in his youth, was literally a barefoot sheepherder – followed a thespian sibling into a theatrical troupe. After marrying and having a son, he moved his family back to Idaho, where the threesome landed a radio gig singing Western music. Impressed by Idaho’s popular ‘cowboy governor’, a New Dealer named C Ben Ross, Taylor jumped into politics. After three unsuccessful primary runs, Taylor – who rode a horse across the state to publicise his candidacy – managed to win one of Idaho’s US Senate seats in 1944.

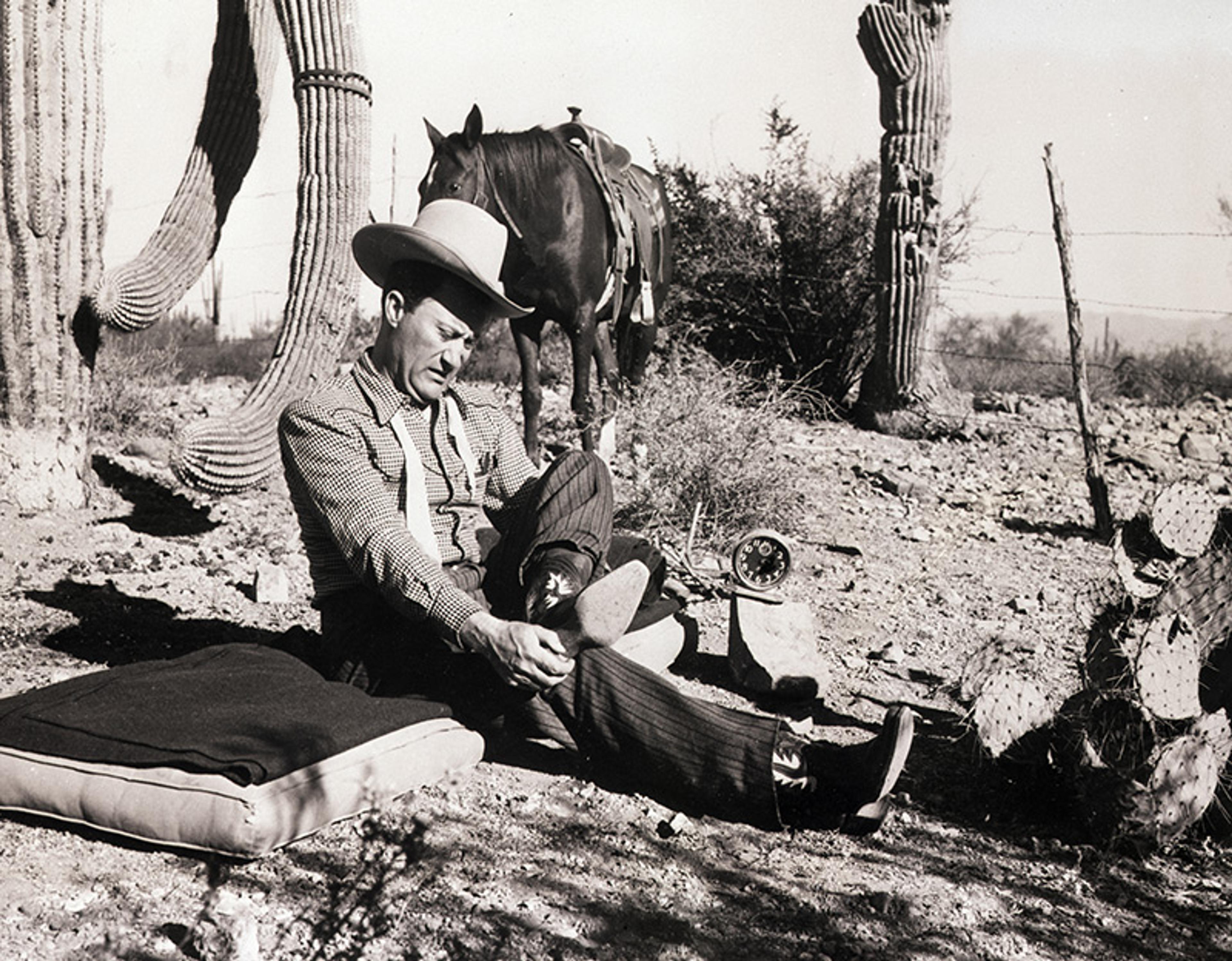

The Democrat Senator for Idaho, Glen H Taylor, taking a break near Tucson on 30 October 1947 during his trip from the West Coast to Washington, DC. Photo by Bettmann/Getty

He promptly made himself ‘one of the most useful Senators the country has’, according to the journalist John Gunther. Beyond supporting reclamation, price controls and unions, Taylor – like many Arizona Democrats – was moving toward a progressive vision that included a commitment to racial justice. In 1947, he rose in the Senate to challenge the seating of the Mississippi senator Theodore Bilbo, who had advocated the use of violence to stop Black people from voting. Taylor’s motion succeeded. Despite having developed a warm friendship with Harry Truman, meanwhile, Taylor began to criticise him for his weakness on civil rights issues and his hawkishness (which, argued Taylor, made tensions with the Soviets worse). As he had once done in Idaho, Taylor donned his Stetson and rode a horse across the country in order to decry Cold War brinksmanship. A year later – in 1948 – Taylor accepted the Progressive Party’s nomination for vice president.

Taylor’s decision to join Henry Wallace’s ticket was an enormous mistake – Cold War hysteria gripped the country. Despite promising early polls, the ticket received only 2.4 per cent of the vote. Taylor’s focus, however, was not solely on winning. He sought to use his candidacy to promote the causes dear to him, particularly civil rights (arguably, he and Wallace succeeded in that endeavour by pushing Truman to take a stronger stand). His first campaign stop was at a Birmingham church, where Bull Connor’s police arrested him and gave him a beating for attempting to enter through a ‘coloured only’ door. Not surprisingly, Taylor lost the 1950 Idaho Senate primary; voters were in no mood to re-elect a ‘communist’. In 1956, Taylor ran again, losing the primary by the thinnest of whiskers. The victor who went on to win the general election, however, wasn’t any John Birch Society racial reactionary. He was another ardent progressive, Frank Church.

Gene Autry was a ‘New Deal cowboy’ who made movies and sang music to popularise Roosevelt’s policies

Modern Democrats might be forgiven for scratching their heads at the idea of a cowboy super-progressive from Idaho. Scholars have painted the cowboy not just as a ‘get-the-government-out-of-my-business’ icon of Movement Conservatism, but also as an icon of imperialism, racism and misogyny. Taylor, however, wasn’t the only cowboy progressive of the first half of the 20th century. As Greg Grandin points out in The End of the Myth (2019), quite a few ‘cowboy radicals’ found homes in the Industrial Workers of the World, most notably Big Bill Haywood, who fled to the Soviet Union in 1921 to escape prosecution under the Espionage Act. Though less radical than Haywood, other cowboy politicians in Mountain West states endorsed activist government. The most successful of them included Taylor’s fellow Idahoan, C Ben Ross; Wyoming governor and senator, John B Kendrick; and Arizona senator Henry Ashurst (‘Silver-Tongued Sunbeam of the Painted Desert’). In Texas, meanwhile, an even more powerful cowboy politician and civil rights supporter, Lyndon Johnson, rose to prominence.

Cowboy progressives also shaped popular culture. Will Rogers, the cowboy humorist from the Cherokee Nation, became the nation’s most popular ‘philosopher’ in the years leading up to the Great Depression. According to his biographer, he ‘possibly did more than any other American to convince the public to accept the overall New Deal’. Rogers was helped in that endeavour by Gene Autry, the nation’s leading cowboy singer from the 1930s until his retirement in 1962. Autry was a self-proclaimed ‘New Deal cowboy’ who made movies and sang music intended to popularise Roosevelt’s policies. He also wrote the ‘Ten Cowboy Commandments’, which demanded that the cowboy ‘must not advocate or possess racially or religiously intolerant ideas’. Though he turned conservative in his later years (trailing his herd of fabulous riches), he made appearances for progressive Democrats into the 1950s, including both McFarland and Lyndon Johnson. Another friend of Johnson, the great cowboy folklorist J Frank Dobie, stood even further to the Left. In the 1940s – at the time Arizona Democrats put civil rights on their political map – Dobie spoke alongside civil rights leaders in Texas and wrote anti-monopoly screeds that the FBI deemed communistic.

Despite the plenitude of cowboy progressives, the cowboy-as-reactionary remains ubiquitous in the annals of scholarship. The history of cowboy progressives has yet to be written. Scholars who may wish to pursue that task would do well to follow the lead of the historian Jack Weston, author of the monograph The Real American Cowboy (1985). Weston carefully appraised – and denounced – the racism among both real cowboys and their mythic counterparts. Weston, however, argued that the cowboy myth – despite its racist freight – was created not as a weapon against Reconstruction era racial reforms, but as compensation for the alienation that Americans experienced in the Gilded Age: their separation from nature, their diminished power to control their fate, their need for ‘a fantasy of a preindustrial, rural society’. The chronology of the cowboy hero supports his thesis. The first cowboy novel to achieve notable commercial success – Prentiss Ingraham’s Buck Taylor, King of the Cowboys (1887) – appeared fully 10 years after the Compromise of 1877 ended the Reconstruction era.

None of which is to say that Weston viewed the ‘cowboy myth’ as homogeneous: he distinguished between Horatio Alger-style cowboys of ‘property westerns’ like Owen Wister’s novel The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains (1902) and ‘community-saving’ cowboys of dime novels, Police Gazette tales, and B westerns. The community-savers, argued Weston, remained staples in popular culture into the 1950s, when property-saving cowboys – like John Wayne in Red River (1948) – crowded them out.

Arguably, cowboy progressives like Glen Taylor adopted the ethos of the community-savers. Behind that ethos, or perhaps alongside it, stood the old populist resistance to monopolies, economic imperialism, and the ‘Eastern establishment’. Even if the West didn’t always elect cowboy figures, the progressives whom they did elect reflected populist sensibilities.

Montanans in particular elected a series of progressives to the US Senate between the 1940s and ’70s – James Murray, Mike Mansfield, Lee Metcalf – all of whom served multiple terms. The man who defeated Taylor in Idaho’s 1956 primary and went on to win the general election, Frank Church, was yet another ardent progressive who held disdain for the ‘Eastern establishment’. Church won election three more times before losing by less than 1 per cent in the Reagan landslide of 1980 (he may well have prevailed had not Jimmy Carter conceded before the polls closed in Western states). Other progressives from the Mountain West joined their ranks: Frank Moss of Utah; Gale McGee of Wyoming; Howard Cannon and Alan Bible of Nevada; Joseph Montoya of New Mexico. Their voices melded in the Senate with progressives from the prairie West: George McGovern of South Dakota; Quentin Burdick of North Dakota; Ralph Yarborough of Texas.

A Western, ‘cowboy’ president led the country into Vietnam, and Western senators vociferously opposed

Lest we imagine that such men were economic populists but racial reactionaries, we might want to examine Senate voting patterns. It was Mansfield who, as senate majority leader, found the votes necessary to end debate after a two-month filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by pro-segregation Southern Democrats. His colleague Lee Metcalf played a key role in ending the filibuster, too, while serving as the Senate’s president pro tempore. Nor were they alone among Western progressives who supported civil rights legislation. If we examine Senate vote totals on the five most important civil rights bills of the 1950s-60s – the Civil Rights bills of 1957, 1960, 1964 and 1968, along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – we find that senators from the eight Mountain West states (Montana, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico) collectively voted in favour of them by a margin of 66-4 (compared with a collective vote in the entire Senate of 364-102). Not a single Mountain West Democrat voted nay.

The only Western state whose Congressional representatives frequently voted against those bills was Texas, which partook of both Dixie’s traditional racism and the West’s nascent racial progressivism. Even as Texas congressmen often (but not always) voted against civil rights, however, Texas’s Democratic senator Ralph Yarborough voted yea on all five key civil rights measures. Its other Democratic senator, Lyndon Johnson, pushed through the 1957 bill, strongly supported the 1960 bill, and, as US president, signed into law the others.

Johnson’s great failing, of course, was the Cold War imperialism that Glen Taylor deplored. If a Western, ‘cowboy’ president led the country into Vietnam, however, it was also Western senators who were among the first – and the most vociferous – in opposition. Foremost among those voices were Mansfield, Metcalf, Church and McGovern. ‘Do we think,’ asked Church, ‘that a white nation is going to be upheld in fashioning the destiny of Asia?’ As the historian Robert David Johnson reminds us, an even earlier generation of Western progressives – including William Borah of Idaho, Burton Wheeler of Montana and George Norris of Nebraska – had developed a ‘blistering critique of American military interventionism’ (including intervention in Latin America) during the 1920s and ’30s. Their ‘radical anti-imperialism,’ writes Johnson, ‘was unique in its consistency and forcefulness in the annals of congressional dissent.’ It was Borah who inspired Church, who not only criticised imperialist foreign policy but also led the Senate investigation that revealed the CIA’s rampant abuses undertaken in the cause of Cold War imperialism.

It was Western progressives, moreover, who sponsored the Indian Reorganisation Act of 1934 (which sought to end the erosion of tribal lands and strengthen tribal governments) and who passed the first state-level old age pensions, setting the precedent for Social Security. It was Western states, too, that first extended full suffrage to women. To be sure, the desire to enlarge the electorate to counter newly enfranchised people of colour played a role in the Western suffrage movement, as did maternalism (meaning men’s approval of women as wives and mothers whose moral voice deserved a hearing). Recognising those phenomena, however, doesn’t negate the fact that Western states struck a blow against patriarchy years before the rest of the country did. Consider the chronology: Wyoming granted full suffrage to women in 1890 (its territorial legislature having granted suffrage in 1869); Colorado in 1893; Utah and Idaho in 1896; Washington in 1910; California in 1911; Arizona, Kansas and Oregon in 1912; Montana and Nevada in 1914. Not a single state outside the West enacted full women’s suffrage until New York did so in 1917.

Given that the Mountain West often led the country in progressive reform, why did so much of it become a bastion of conservatism, particularly in the 1980s and ’90s? A host of scholars have analysed the rise of Movement Conservatism in the West and South between the 1950s and ’90s. But what no historian has done, so far as I know, is to analyse how Western Democrats changed in those same decades. The simple answer, of course, is that culture wars – battles over gun control and abortion rights, primarily – turned Western ruralites into ardent conservatives. Also, more than a few Westerners viewed people of colour as shiftless dependents who forever sought ‘special favours’ from government. The reasons for the West’s Rightward shift, however, transcend any simple racial explanation.

First, much of the rural West – like the Rust Belt – experienced a series of economic shocks in the 1970s and ’80s. The lumber industry went into decline along with the mines. Farmers in the Plains and in parts of the Mountain West, moreover, experienced a devastating bust – followed by a spate of suicides – thanks to falling crop prices and Jimmy Carter’s decision to embargo grain sales to the Soviet Union. Meanwhile Democrats began touting environmental politics. Again and again, they made carving out ‘wilderness areas’ high priorities, notwithstanding opposition from ruralites who depended on resource extraction for jobs. They often modified their economic politics, too, by supporting free-trade agreements, outsourcing and investment banks.

It would be foolhardy to suggest that rural, Western communities had once been stalwart progressives. They had voted progressive largely out of economic self-interest (agricultural price supports; infrastructure development; Social Security; the GI Bill). When Democrats began to cater more to the interests of affluent urbanites, those in the countryside (and some in suburbia) changed allegiances. Though Democrats continued to speak the language of class – they never entirely ignored ruralites – they more often spoke on behalf of the prosperous and educated.

There will likely never be another Glen Taylor, singing his way across Idaho

And therein lies a stunning irony: the West gradually turned Republican between the 1950s and ’80s as its residents became ‘higher paid, less unionised, better educated, more professional and increasingly middle to upper class’, as Arthur H Miller put it in 1987. (In other words, the West became more conservative not because it was captive to any cowboy myth, but because it became prosperous.) And yet the Mountain West – which now has nine Democratic senators and only seven Republicans – has shifted back to Democrats in recent years for pretty much the same reasons (even as some of its poorest counties have often shifted Rightward). ‘Class is not dead,’ declared a team of social scientists in 2007, ‘it has been buried alive under the increasing weight of cultural voting, systematically misinterpreted as a decline in class voting.’ What is true of the West is true for the rest of the country: 26 of the nation’s 27 richest Congressional districts are represented by Democrats. The bluest island in Wyoming is what Justin Farrell calls a ‘billionaire wilderness’ full of well-meaning environmentalists who are equally dedicated to neoliberal economics, whence their wealth derives.

There will likely never be another Glen Taylor, singing his way across Idaho, bringing ruralites into his progressive, pro-civil rights constituency. To the degree they still exist, cowboy politicians have become a phenomenon of the Right, as Beckwith’s aforementioned Time photo essay suggests. Democrats might field the occasional wealthy Montana candidate with a ranching background, but they have trouble speaking to white rural and blue-collar constituencies. In those fallow fields grows the weed of Trumpism.

US historians, meanwhile, abandoned the new labour history at roughly the same time that Democrats began to turn away from rural and labour constituencies. Interest in the history of Western populism, or Western anti-imperialism, or Western progressivism, for that matter, has plummeted. What both historians and modern progressives embrace instead is a theory of permanent Western depravity epitomised in the idea of what one historian in 2019 termed a ‘belt of white supremacy’ (roughly encompassing Texas and the Mountain West, minus Colorado and New Mexico) and the continuation of the Confederacy.

That sort of thinking isn’t about understanding history. It’s about cementing current constituencies. It’s about drawing Manichaean lines between ‘us’ and ‘them’ that white supremacists – real ones, not ‘everyone who votes Republican’ – have long desired. It’s probably not going to lead to civil war, but neither will it bring progressive advance.

Is it possible to escape that political impasse? Can cowboy progressives – or some modern equivalent – make a comeback? Can Western Democrats, or Democrats nationally, find a way to blend New Deal-style economic progressivism with racial and gender progressivism and thus win back enough rural and blue-collar whites to prevail in elections? Or will cowboy-booted Republican cultural warriors (think Josh Hawley of Missouri) fashion an economically progressive message of their own that resonates among both whites and people of colour? Both parties have the capacity to do that, but institutional inertia and the power of donors will likely block them, unless the country becomes locked in a deep recession. Unless and until there is a crisis, stasis will likely prevail.

A longer version of this essay appeared in the ‘Western Historical Quarterly’, vol 53, No 1 (Spring 2022).