The smile is the most easily recognised facial expression at a distance in human interactions. It is also an easier expression to make than most others. Other facial expressions denoting emotion – such as fear, anger or distress – require up to four muscles. The smile needs only a single muscle to produce: the zygomaticus major at the corner of the mouth (though a simultaneous twitching of the eyelid’s orbicularis oculi muscle is required for a sincere and joyful smile). As well as being easy to make and to recognise, the smile is also highly versatile. It may denote sensory pleasure and delight, gaiety and amusement, satisfaction, contentment, affection, seduction, relief, stress, nervousness, annoyance, anger, shame, aggression, fear and contempt. You name it, the smile does it.

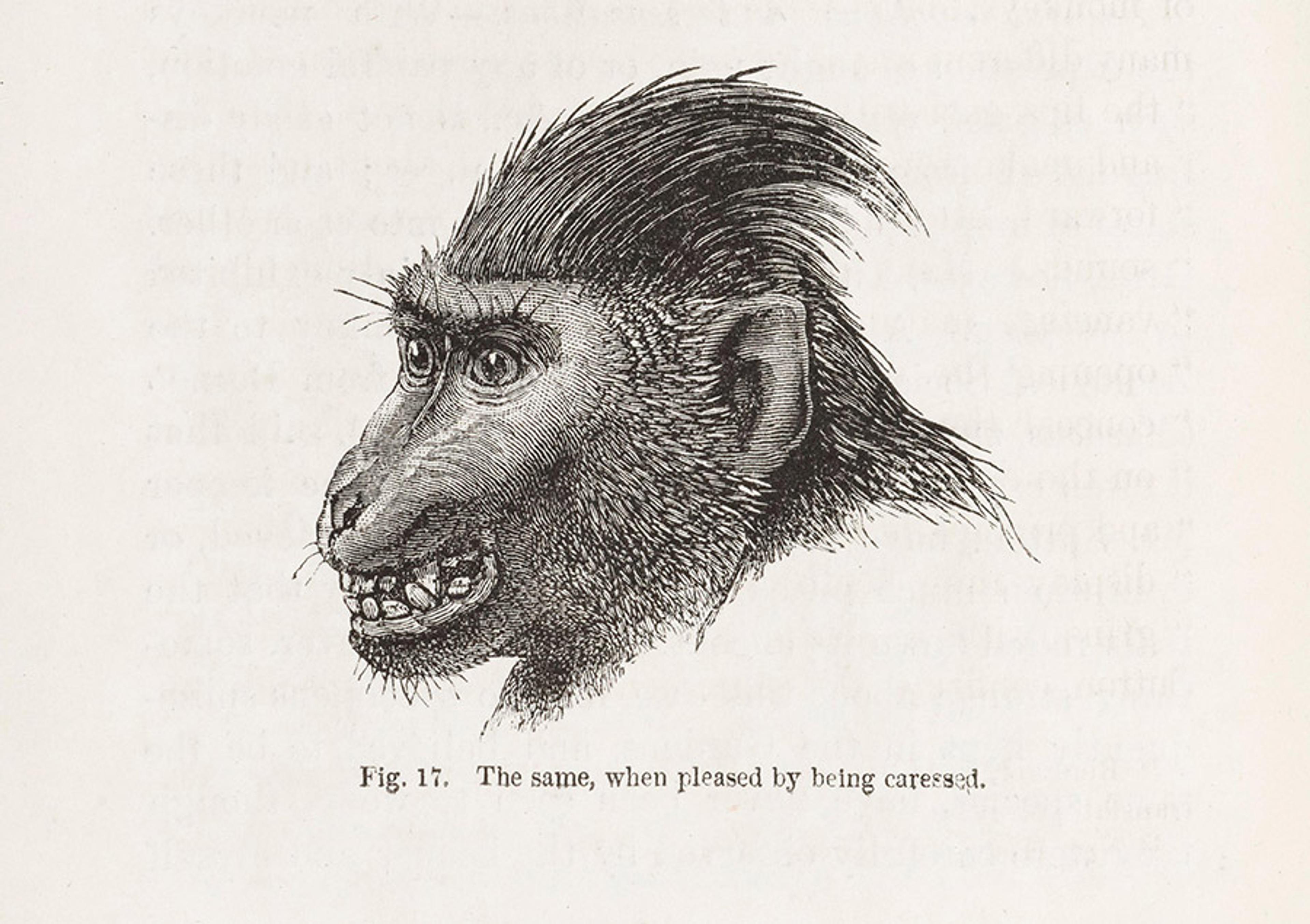

The smile comes easy to human beings. The facial muscles required to smile are in fact present in the womb, ready for early deployment to anxious parents. The smile may even predate the human species. Many great apes are known to produce them, suggesting that the smile first appeared on the face of a common ancestor well before the existence of Homo sapiens. It was Charles Darwin, in his classic The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), who gave the first scientific demonstration of a great ape smiling. He also showed that the great apes’ smile has something of the gesture’s polyvalence among humans: it can denote pleasure (notably under tickling) but also aggressive self-defence.

From The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) by Charles Darwin. Courtesy the Wellcome Collection, London

The smile has always been with us then, and it would appear it’s always been the same. It seems only one step further to claim that the smile has no history. But this would be far from the truth. In fact, the smile has a fascinating, if much-neglected past. In order to access it, we need first to take on board more general cultural factors. The ubiquity and polyvalence of the smile means that, in social circumstances, for example, it is not enough to see someone smiling. One has to know what the smile intends. The expression needs untangling, deciphering, decoding. In this, it resembles the wink. As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz pointed out in 1973, the wink is physiologically identical to the involuntary eyelid twitch we call a blink. For a wink to be understood as a wink rather than a blink, winker and winked-at need to understand the cultural codes in play. And these, of course, can differ very markedly.

In the West, we tend to acknowledge the variability of codes in terms of space and diversity: there is a sense that Western smiling culture differs from that to be found, for example, in Japanese and Chinese societies. Yet the smile shows chronological as well as spatial differentiation. In the ‘archaic smile’ that is seen in certain ancient Greek sculptures, for example, the lips are formed into a smile. Yet classicists are sceptical that this does in fact represent the expression as we know it. It may just be intended to evoke general health and contentment. In other words, the smile existed, but we don’t know what it meant.

The archaic smile of the kouros (c530 BCE, or modern forgery). Courtesy the Getty Museum, LA

Ancient Romans showed another variant. If we take their vocabulary at face value, they did not distinguish between a smile and a laugh, contenting themselves with a single Latin verb – ridere – for both. Only towards the end of the Roman Empire did a diminutive – subridere – enter the language. This came with the derived noun sub-risus (later, surrisus) a ‘sub-laugh’– a little or low laugh – associated with mockery. It retained this lesser status and this diminutive form, distinguishing it from the laugh as it entered the Romance languages in the High Middle Ages. Around 1300, for example, French contained words for laughing (rire) and laughter (le rire or le ris) and smile (sourire, from sous-rire).

At roughly the same times and in a similar manner, Italian adopted ridere and sorridere, Spanish reir and sonreir, Portuguese rir and sorrir, and Provençal rire and sobsrire. A specific word for ‘smile’ emerged in Celtic and Slavic languages around then too, but using a non-Latinate term: the Danes got smile and the Swedes, smila. English finally got its ‘smile’ from a High German or Scandinavian source. Revealingly, it was at much the same moment that the smile entered the Western art tradition, in the form of the famous ‘smiling angel’, created between 1236 and 1246, that adorns the west front of the great cathedral in Reims in northeastern France. Historians have hailed this delightful and very modern-looking expression as marking the advent of new civilisational values in Western culture.

There are certainly examples of open mouths and teeth, but they are invariably negative in their associations

The smile as we know it was thus out and about in the Western world from the 13th century onwards. Literature demonstrates that, in the centuries that followed, it evoked much of the range of feelings that we attach to it in our own culture. Petrarch dreamed of ‘the brightness of the angelic smile’ of his lover, and while this kind of gentle lyricism can also be found in William Shakespeare’s sonnets, the Bard knew that ‘one may smile, and smile, and be a villain’. Renaissance painting welcomed and adopted the smile, too. Its meaning was not always, however, crystal clear: witness the legendary if infuriatingly ambiguous smile playing on the lips of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503-17).

Yet if the smile was alive and well in Western culture, it was not yet our own. In Western art, it differed in one highly significant respect: the smiling mouth was almost always closed. Teeth appear in facial representations extremely rarely. One can scan drawings, paintings and sculptures from before the 19th century in art galleries and museums the world over without finding a single example of a tooth-baring smile of the kind that is so common in our own day. There are certainly examples of open mouths and teeth, but they are invariably negative in their associations.

It is tempting to ascribe this state of affairs to the unhygienic state of mouth. But, in fact, skeletal remains from late medieval cemeteries suggest that teeth were then less affected by cavities than they would become from the 18th century onwards, with the mass advent of sugar into Western diets. The reason for the tight-lipped primness of the smile in the period inaugurated by the smiling angel of Reims seems to have owed everything to cultural values rather than biological deficiencies.

Three factors operated to minimise representation of the expression. First, there was a close association between the open mouth and the lower orders. Opening the mouth invariably to reveal inner horrors was something only plebeians did. This artistic convention reflected social norms current in polite or patrician society that were set out in the early 16th century by two highly influential writings: the Mantuan diplomat Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (1528) and the Dutch humanist Erasmus’s On Civility in Children (1530). Both strongly advised against opening the mouth for all but fulfilling the basic biological needs: to do so in any other way marked one down. Laugh if one must, was the message, but do so silently and with one’s mouth buttoned up in a seemly, decorous and polite way. Frans Hals’s Laughing Cavalier (1624), for example, may have a broad grin, as the title suggests: but his lips are sealed. Were they not, he would be as good as denying his status as a gentleman.

The two seminal texts were frequently re-edited over the next few centuries and translated into many languages. Erasmus first appeared in English in 1532 and Castiglione in 1561 (the version seemingly known to Shakespeare). Though addressed to courtiers and schoolchildren respectively, the texts reached far wider audiences, particularly through the Renaissance genre of the conduct book, which purported to show readers how polite people behaved in every facet of their lives. These texts formed part of what the German sociologist Norbert Elias in 1939 called ‘the civilising process’, a kind of behavioural revolution, one of whose key features was control of bodily orifices, particularly in public spaces. Mouths should be kept closed when eating, for example, spitting was taboo, noses should remain unpicked, ears were not to be probed in public, and eyes should not stare. And there should be no farting.

The Shrimp Girl (c1740-45) by William Hogarth. Courtesy the National Gallery, London

Doubtless, in real life, these were rules there to be broken. But breaking them revealed one’s low character. Or – and this was the second factor in play, in art as in life – it betrayed a loss of reason. The mouth lolling open was an accepted way of depicting the insane, but it went further than that, and encompassed the representation of individuals whose rational faculties had been placed in abeyance, by passions or base appetites. This was one reason why some of the tiny number of portraits showing white-tooth smiles are of children – William Hogarth’s The Shrimp Girl (c1740-45) is a good example. By definition, she had not reached the age of reason and learnt how to be polite. (Or maybe she was from the lower orders and would never know better.)

When the soul was calm and tranquil, the face was perfectly at rest

The third factor explaining the absence of positive depictions of open mouths in Western art related to what were known as ‘history paintings’ depicting scenes from ancient history or scripture. Individuals in such scenes are often shown as in the grip of a strong emotion such as terror, fear, despair, rage or ecstasy (whether spiritual or fleshly). In the 17th century, Louis XIV’s premier painter, Charles Le Brun, sought to codify conventions concerning the representation of the passions in history painting. He drew on implicit norms that he had detected within Western art dating back to antiquity, but also sought confirmation of his ideas in the cutting-edge physiology of the philosopher René Descartes.

Descartes argued that the pineal gland was the ‘seat of the soul’, located within the head, between the eyes and behind the bridge of the nose. The gland was where thought and sensation were formed, and this influenced, Descartes argued, the flow of animal spirits to the muscles – including, importantly, the muscles of the face. For Le Brun, it followed that, when the soul was calm and tranquil, the face was perfectly at rest. Conversely, when the soul was agitated, this expressed itself on the face – particularly around the eyebrows, the facial feature located closest to the pineal gland. The more extreme the passion, the more contorted the muscles in the upper part of the face – and the more the lower part of the face came to be affected, too. It needed very extreme emotions for the mouth to open widely.

Le Brun’s theories were widely diffused in Europe from the late 17th century. Even though the Cartesian view of the soul subsequently declined, the facial drawings with which Le Brun had illustrated them remained highly popular. Indeed, throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th, copying his gallery of expressions became a standard way that amateur artists learned how to draw and paint faces. The expressions also found themselves appearing in other types of paintings. Dutch genre painting showed inebriated figures lolling around in inns and taverns laughing uproariously or caught up in violent dispute. Teeth also appeared in some self-portraits by artists presenting themselves in a sardonic manner – a tradition that went back to Rembrandt and beyond. But the regular portrait stayed loyal to the courtly shut-lipped tradition of Castiglione, the Mona Lisa and the Laughing Cavalier.

Until, that is, 1787. For it was in that year in Paris that Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (related by marriage to Louis XIV’s court painter) exhibited a self-portrait in the annual Salon in the Louvre (where the painting remains). With her daughter at her knee, she graciously looks out at the viewer and smiles with decorous charm, revealing her white teeth.

Madame Vigée Le Brun and her daughter, Jeanne-Lucie-Louise, called ‘Julie’ (1786) by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. Photo courtesy RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)/Michel Urtado

The art world went into a state of shock. ‘One element of which artists, people of good taste and collectors all disapprove,’ wrote one critic, ‘and of which there is no precedent stretching back to Antiquity, is that as she laughs she shows her teeth…’ In late 18th-century Paris, a new phenomenon had marked its arrival in Western culture, transgressing all the norms and conventions of Western art. The modern smile was born.

Mme Vigée Le Brun may have been initiating something of an artistic revolution on the cusp of the more famous political revolution of 1789. But there is evidence that her painted smile reflected changes already taking place within French society more generally. People were, it seems, smiling more and seeing new positivity about the gesture. Paris was in the vanguard of this development. The French capital had established itself as a kind of influencer avant la lettre, which set trends that the rest of Europe followed as regards fashionable behaviour and commodities. The kind of stiff gravitas, conventionality and facial immobility prized at the royal court at Versailles lost its attraction for the livelier, more dynamic metropolitan culture emerging in the French capital. In salons, coffee-houses, theatres, shops and the like, more relaxed and unstuffy behaviour was the norm.

The white-tooth smile, moreover, was invested with new prestige by the cult of sensibility that swept through Europe at mid-century, encouraged by the bestselling novels of Samuel Richardson (Pamela, Clarissa) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, Émile). Modern readers of these novels are usually struck by the huge amount of weeping and sobbing that goes on in them, as their protagonists’ virtue is placed under cruel assault. But the characters prevail, significantly, with a sublime smile on their lips.

This was important as these novels and others like them generated a wish among their readers to model their own behaviour on the fictional characters’. This trend resembles the impact of Hollywood stars and social media influencers in more recent times. The virtuous and transcendent smile showcasing healthy white teeth in the novels became a model for the Parisian social elite in real life. It became not only acceptable but even desirable to manifest one’s natural feelings among one’s peers. English travellers expressed amazement at how frequently Parisians exchanged smiles in everyday encounters. The city had become the world’s smile capital.

If the cult of sensibility gave novel readers the wish to smile in this fashionable way, Parisians were also lucky enough to have technical assistance at hand. The French capital had become a renowned centre for dental hygiene. Across Europe and indeed the wider world prior to the early 18th century, mouth care had been a clumsy combination of strategic tooth-picking, pain-relieving opiates and indiscriminate tooth-pulling. Now, a new kind of mouth-care expert emerged in Paris, replacing the fairground tooth-pullers of yore: the dentist.

Under the Reign of Terror, smiles had to stay beneath the parapet for political reasons

The term was coined in Paris in the 1720s and entered the English language at mid-century. It denoted a specialist with surgical and anatomical training who deployed artful instrumentation on dental care. The new dentists could clean, whiten, align, fill, replace and even transplant teeth so as to produce a mouth that was cleaner, healthier and – in smiling – attractive. European gentlemen undertaking their Grand Tour would drop in to Paris to get their teeth fixed. Parisian newspapers were crammed full of publicity vaunting mouth cosmetics and instruments of every description. Alongside toothpicks, tongue-scrapers, breath-sweeteners, tooth-whiteners and lipsticks was found the toothbrush – a sure harbinger of a smiling modernity, which was invented at this very moment. The perfection of the invention of porcelain dentures in the late 1780s by the Parisian entrepreneur Nicolas Dubois de Chémant presaged a booming new industry in false teeth. It meant that one could perform the new white-tooth smile without a tooth of one’s own in one’s head.

In this context, we can see the Vigée Le Brun as a kind of high-art advertisement for Parisian preventive and cosmetic dentistry and fashion. The public showing of the portrait in the Salon ensured a widespread impact: viewers took the new smile with them to their homes across the world. A radiant future looked assured.

In the event, the triumph of the Parisian open-mouthed smile was both localised and short-lived. It would have to wait more than a century before it established its sway worldwide. Even – and perhaps especially – in Paris, the impact of the Vigée Le Brun smile was short-circuited by the French Revolution two years later and the diffusion of a political culture that found this kind of smile problematic. Even before the Revolution, the cult of sensibility was being challenged by neo-classical taste. The epic paintings of Jacques-Louis David, for example, were all about jutting jaws, facial rigidity, stiff upper lips and quasi-operatic bodily gestures. This style of representation prevailed after 1789. Indeed, under the Reign of Terror (1793-94), smiles had to stay beneath the parapet for political reasons. To ardent revolutionaries, smiling seemed to hark back to the dolce vita scandalously enjoyed by pampered aristocrats under the Ancien Régime. True patriotism had no time for a gesture that seemed to mock republican seriousness.

Furthermore, the open mouth that people increasingly associated with the French revolutionaries had gothic, ghoulish and melodramatic associations. The facial mutilations of victims by angry mobs, for example, often focused on the mouth: the state official Joseph-François Foullon de Doué – who in 1789 was held to have urged the people of Paris to eat grass if they could not afford the price of bread – had his comeuppance when his severed head was paraded around the city on the end of a pike, with straw stuffed into its mouth. Goya depicted the revolutionaries as the god Saturn devouring his children, according to one interpretation of his haunting painting. English political cartoonists doubled down on this, presenting the Parisian popular classes as slavering cannibals. Even the porcelain dentures that Dubois de Chémant had bestowed on humanity became the object of the sarcastic mockery of the English caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson. Such images lingered in European imaginations, crowding out memories of more innocent times.

A French Dentist Shewing a Specimen of His Artificial Teeth and False Palates (1811) by Thomas Rowlandson. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

If in Paris the Vigée Le Brun smile had lost its allure and been consigned to the dustbin of history, this owed something also to a crisis in medical services. Revolutionary legislation closed the niche within the medical system that dentists had occupied, and there was no provision for training in dental surgery. For a century, dentists had no institutional status, and soon found themselves back in a situation where they were competing for customers with the charlatan tooth-pullers of old.

The smile went into hibernation as a public gesture in the West for more than a century. It was only in the early 20th century that it re-emerged under the influence of a range of factors. Better dentistry was a significant part of the story, and the world leader was not Paris but the United States, which had been among the earliest countries to professionalise dental training from the early 19th century onwards. Yet, as in the 18th century, the triumph of the smile owed as much to cultural trends as to the supply of dental expertise and proficiency. Highly visual advertising practices, Hollywood star image-making and snapshot photography also played a role. As anyone with family photograph albums going back that far will discover, it was from the 1920s and ’30s that smiles appear for the first time – precisely the period when individuals began to say ‘cheese’ when confronted with a camera. Portraiture had become democratised – and smilified.

From the turn of the 21st century, iPhone photography and social media confirmed the preferred individual expression of social identity was through smiling. The technologies also worked to erode barriers with global smiling cultures that had formerly been less reflective of Western practices. One in every five of the more than 500 million Twitter messages sent each day, it has been calculated, contains an emoji. It is the lingua franca of the globalised mass culture of the electronic age. The most utilised of all the 3,000-plus available emojis is the ‘smile with tears of joy’, an upgraded version of the original smiley.

In 2019, the long march of the modern (Western) smile received a severe jolt, with the appearance of COVID-19. Suddenly, that expression retreated behind a surgical mask. It is true that the perceptive among us may have been aware that a genuine and sincere smile causes a detectable crinkling of muscles around the eyes. But then we are not all so perceptive. And who smiles only sincerely anyway? The emoji registered the hit. Though the ‘smile with tears of joy’ maintained the top spot in global usage, another emoji surged dramatically: the surgically masked face. The popularity of the masked-face emoji became so intense that when, in November 2020, Apple released its annual additions to the range, it was thought wise to tweak the mask emoji, adding colour to the cheeks and a meaningful creasing around the eyes so as to give the appearance of smiling under the mask. The smile, it seemed, was fighting back. And indeed it looks unlikely to lose its iconic cultural value and global appeal. A receding pandemic status across the world gives everyone something to smile about.