On 5 August 2014, a celebrated Japanese scientist was found dead, hanging by his neck at his workplace, his shoes politely removed and placed on the landing of the stairs. Yoshiki Sasai, 52, was a legendary stem-cell expert, widely regarded as an exceptional scientist, who worked at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe. Seven months before he killed himself, Sasai and colleagues in Japan and Boston announced a stupefying research breakthrough in two papers in Nature. They claimed that ordinary mouse blood cells could be transformed into powerful stem cells – the holy grail of regenerative medicine – by simply bathing them in a mildly acidic solution (called STAP, for stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency).

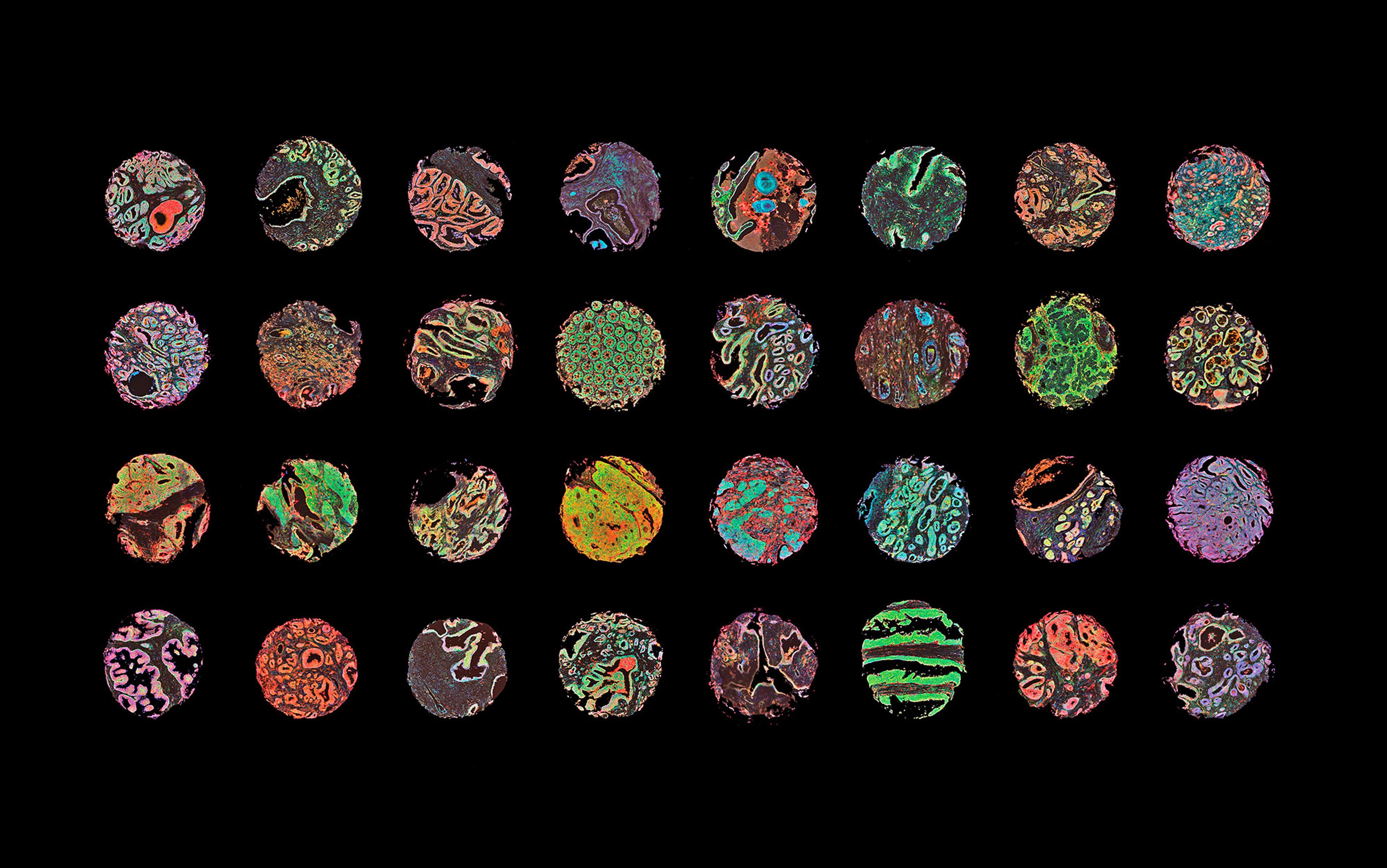

Almost instantly, the work was called into question. Accusations surfaced in the science blogosphere that images in the papers had been duplicated or altered, and at least eight scientists announced that they were unable to reproduce the experiment. In February 2014, RIKEN launched an internal investigation, and found the 30-year-old lead author, Haruko Obokata, guilty of scientific misconduct (which includes falsification, fabrication, or plagiarism). She had been Sasai’s protégé.

In June, Science reported that earlier versions of the STAP work had been rejected by three top journals: Cell, Science and even Nature itself. Science quoted RIKEN’s report, where peer reviewers raised many troubling questions. ‘This is such an extraordinary claim that a very high level of proof is required,’ wrote one. Another said the paper was ‘simply not credible’. Scientists once again took to the blogosphere asking why Nature had published flawed work and whether journals today value hype over substantive science.

In July, Nature retracted both papers – essentially stamping them with a scarlet letter. Retraction lofted the scandal to worldwide infamy. One evening, when Obokata left work in a taxi, a reporter on a motorcycle started following her. She stopped at a hotel, but was pursued up the escalator and into the bathroom by five journalists, including a cameraman, and sprained her right elbow trying to get away.

Then, in August, Sasai killed himself. This was in spite of the fact that he’d been cleared of fraud, and his share of responsibility was linked to lack of proper oversight. In a suicide note to his family, he wrote that he was ‘worn out by the unjust bashing in the mass media’. His brokenhearted family simply said: ‘We feel crushed by a deep sorrow… we see nothing but despair.’

That same month, RIKEN also announced it was conducting a second investigation into possible laboratory contamination during the experiments. The institution’s reputation was still so damaged that in late October six top administrators volunteered to atone by returning between one and three months of their salary.

Based on this narrative, one might conclude that retraction is a near-perfect guillotine, heartless perhaps, but an alarmingly potent tool for self-correction in science.

That is not the case. The STAP story is a tale of all that’s troubled in the scientific enterprise today: scientists seeking demigod status and flying too close to the sun with their claims; journals smitten with a potential blockbuster finding, and overlooking vexing questions ahead of publication; retractions on the rise, entering mainstream awareness, and leaving an entire scientific community frightened of the resulting stigma.

Retraction was meant to be a corrective for any mistakes or occasional misconduct in science but it has, at times, taken on a superhero persona instead. Like Superman, retraction can be too powerful, wiping out whole careers with a single blow. Yet it is also like Clark Kent, so mild it can be ignored while fraudsters continue publishing and receiving grants. The process is so wrought that just 5 per cent of scientific misconduct ever results in retraction, leaving an abundance of error in play to obfuscate the facts.

Scientists are increasingly aware of the amount of bad science out there – the word ‘reproducibility’ has become a kind of rallying cry for those who would reform science today. How can we ensure that studies are sound and can be reproduced by other scientists in separate labs?

The edifice upon which science is built is self-correction. And self-correction generally works. Scientists make mistakes, and science corrects those mistakes. This happens when results cannot be reproduced, and the original work is found in error. An erratum is issued when errors are relatively minor, and do not invalidate the basic assumptions and conclusions of the study as a whole. A retraction is issued when the study is no longer valid. A retraction withdraws, refutes or reverses the entire scientific finding.

It is the infamous retractions that mesmerise us, of course. The stem-cell scandals – not just STAP, but also the South Korean researcher Hwang Woo-suk, found guilty in 2009 of embezzlement and bioethical violations after making false claims that he had cloned human embryos and generated cloned stem cells. Or the tumble from grace in 2011 of the prominent Dutch social psychologist Diederik Stapel, who faked data on at least 55 papers on topics such as the human tendency to stereotype or discriminate. Or the infamous 1998 paper in The Lancet by the British researcher Andrew Wakefield and others that linked autism and vaccines, and influenced many thousands of parents on both sides of the Atlantic to stop vaccinating their children.

Woo-suk, who bowed to the judgment, was fired, sentenced to a two-year, suspended prison sentence, and barred from further stem-cell research (though he currently works at another institute). Admitting his error, Stapel lost his job and his PhD. Wakefield lost his UK medical licence, though he defends his research to this day. Most retractions are not as notorious, but studies do show that highly cited papers – those eye-catching findings that the scientific community notices – are more likely to be retracted.

Retraction matters so much because the scientific enterprise is key to our survival

Nobody knows exactly when the first retraction appeared, though Galileo is unforgettable for being ordered to recant his theory that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the centre of the Universe. He was placed under house arrest for life. In modern times, retractions began to trickle out in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that the numbers actually started rising.

By the early 2000s, about 30 papers a year were retracted. In 2014, more than 400 retracted papers will be indexed by the Web of Science, an online database of science publications. The many scarlet Rs have triggered soul-searching essays in big-name journals, such as an essay in this October’s Nature, suggesting that this surge highlights weaknesses in the scientific endeavour itself.

Retraction matters so much to so many because the scientific enterprise is key to our survival, and so that enterprise must be sound. Retraction is today’s ‘window into the scientific process’, to quote the tagline of one of the most-read blogs in science, Retraction Watch (15 million page views in a mere four years, and 125,000 unique visitors a month). The site’s weekly round-up of news and commentary on scientific fraud and error can be as gripping as the latest episode of the TV crime drama CSI.

Yet the system is flawed, in part because retraction carries a terrible sting. In 2008, Joshua Klopper, an endocrinologist at the University of Colorado, briefly considered leaving academia when he was threatened with retraction for reporting an honest error using a misidentified cell culture (a melanoma that was mislabelled as thyroid cancer at labs around the world). He informed the journal, Clinical Cancer Research, and offered an erratum. The editors threatened him with retraction and, according to Klopper, told him that he could file a formal complaint about any other scientists who had published on the same misidentified line. Klopper said: ‘Throw my colleagues under the bus or be the only one slapped with a retraction? This kind of response sets a precedent where nobody who has made a mistake will want to come forward to correct an error.’ Ultimately, the journal relented and, a year later, published an erratum. Klopper told me: ‘It is now one of my prouder moments. I did the right thing.’

If scientists shun retraction, then journal editors willingly follow in their footsteps. ‘Honesty should be a badge of honour for scientists and journals alike,’ says the UK medical editor Elizabeth Wager, who helped draft the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) Code of Conduct. But in a review of the trouble with retractions, Wager and a colleague found journal editors reluctant to retract. And even when they do, they might be vague, as a courtesy to the scientists. When in 2011 Wager and her colleague Peter Williams reviewed 312 retractions from 1998 to 2008, they found that some journals actually omit the reason for the retraction, while others use ambiguous wording or euphemisms. ‘It’s incredibly important that the journals make it clear why an article was retracted,’ said Wager.

Journals are no longer stodgy stuffings in the stacks of libraries: they are slick and beautiful, with arresting headlines that garner major media attention. Top journals compete for submissions by top scientists. A metric called the ‘impact factor’ (which reports the average number of citations of articles a journal receives in a given year) is as potent a calling card as the bestseller list or the top 10 hit songs. The largest academic publishing conglomerates boast fat profit margins of 35 per cent. Losing star contributors could rock the empire.

Wager also thinks journals fear retractions because of potential litigation, and for good reason. Lawyering-up is an increasingly common response to the potential damage inflicted by retraction. In July 2014, Guangwen Tang, a rice researcher at Tufts University in Boston, sued both Tufts and the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, which had announced its intention to retract a paper of hers. She claimed the retraction constituted defamation; the paper still stands.

In October 2014, the Wayne State University pathologist Fazlul Sarkar, recipient of $13 million in grants from the US National Institutes of Health, initiated a lawsuit against a site called PubPeer, which allows anonymous ‘post‑publication’ peer review in the form of comments on a paper. Sometimes such comments have led to retractions. Sarkar’s lawsuit claimed he lost a substantial job offer from the University of Mississippi because of questions raised on the site about his work.

The medical scientist Paul Brookes, a whistleblower from the University of Rochester in New York, ran a blog called Science Fraud for six months. The blog cited 274 papers with apparent problems, leading to 16 retractions and 47 corrections. But in 2013, Brookes had to shut it down under threat of lawsuits.

We need to change the unparalleled power of the published paper

When all is said and done, even retracting a paper might not be enough to kill it. In the world of science, such papers can rise from the grave like zombies, and even receive positive citations. Just take a glance at these depressing numbers: a 1999 study found that 235 papers retracted between 1966 and 1996 received more than 2,000 post-retraction citations but fewer than 8 per cent of those citations acknowledged the retraction. The rest cited the papers as valid.

A 2012 study of 1,779 retracted articles published between 1973 and 2010 found that they continue to be cited as sound many years after retraction notices had been issued. A remarkable 2010 study of Stephen Breuning – formerly a psychologist at the University of Pittsburgh, who had 24 of 25 published articles discredited by the National Institutes of Mental Health, and who in 1988 was convicted of scientific misconduct by a federal judge – found that his papers still received positive citations all the way through to 2006. In fact, an upsurge of positive citations for Breuning started in the year 2000 – as if time had washed away the negatives, replenishing a lost reputation. So although citations of a retracted paper, and of scientist’s work overall, do fall after a retraction, the scientific literature does not purge itself the way it should.

Even more astonishing are the second lives of some retracted papers. Just as one man’s poison is another man’s medicine, one journal’s retraction can be another’s prestigious publication. A 2012 study demonstrating that rats exposed to genetically engineered maize were more likely to develop tumours and die earlier was quickly retracted by Food and Chemical Toxicology after an uproar from other scientists. In 2014, the paper was essentially republished by Environmental Sciences Europe. It was based on the same data, and contained only minor rephrasing.

Despite this kind of snafu, a relentless storm is reshaping the way science is conveyed and received today. Fraud and error are harder to hide, because of the democratising influence of technology and the world wide web. Plagiarism-detecting software, which can scan a paper and give a report within minutes, is widely available. Replication or manipulation of images is easier to sleuth out, because most papers are now widely available in digital versions viewable from any computer. The rise of online post-publication peer review is also reshaping the scientific endeavour before our very eyes.

If all the reforms already available were widely adopted, routine corrections might become commonplace. But these reforms aren’t being widely adopted, yet. The geneticist Roderick MacLeod, of the German bio-bank DSMZ, says: ‘There is a malignant inertia out there. The status quo exerts great power over us, and we tend to do what we always did.’

It is still not mandatory for every scientist to upload raw data to a hosting site (a common one is Figshare), even though online storage is now essentially infinite and cheap or free. Many journals have policies that data should be deposited and freely available, but most do not enforce those policies. And it’s nearly impossible to investigate suspected fraud without access to the raw data. Wager tells of journal editors complaining that authors had conveniently lost data in ‘lab fires, floods, catastrophic computer crashes, or more bizarrely, attacks by termites’.

Science needs to be nudged back to its humble but glorious beginnings, when discovery itself was the means and the end

The pathobiologist Kenneth Witwer of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore found that fewer than 40 per cent of the 127 studies in his specialty field (microRNA) actually submitted raw data. Is reluctance to share data linked with low study quality? Nobody knows. If other scientists – some of whom are superb data sleuths – have access to your raw data, it’s a deterrent to fraud. And it makes sense to store data safely, freely and publicly, even if there’s no misconduct.

Post-publication peer review, taking place entirely online, is another tsunami reshaping the scientific landscape. The largest database of archived peer-reviewed abstracts, PubMed, now allows comments on its PubMed Commons by the scientific community. Any scientist who has had an article published and archived on PubMed can register and comment. Numerous blogs and sites serve as informal reviews, especially of image duplication or fabrication. The whistleblower Brookes recently published a study on internet publicity and corrective action. Although his study was small, it found that papers which received public discussion had a sevenfold greater correction or retraction rate.

Another potential game-changer is a service called CrossMark. For journals that subscribe to CrossMark, every paper is stamped with a digital logo, and any researcher can, at any time, even years hence, click on the logo to see if a paper has been cited, corrected, updated or retracted. This could be a tremendous help to researchers who download their own treasure trove of significant papers, numbering in the thousands – all the while unaware of subsequent changes in a given paper’s status. Unfortunately, CrossMark, which is a relatively new service, has not been widely adopted. In a similar vein, the MacArthur Foundation has funded the first freely available database of online retractions under the auspices of a new group called the Center for Scientific Integrity, created by Retraction Watch to house its efforts.

There’s no doubt that widespread change is underway. But ultimately, for retraction to lose its stigma, and for reforms to be widely adopted, the culture of science itself needs to shift. Ivan Oransky, the co-founder of Retraction Watch, says: ‘We need to change the unparalleled power of the published paper.’

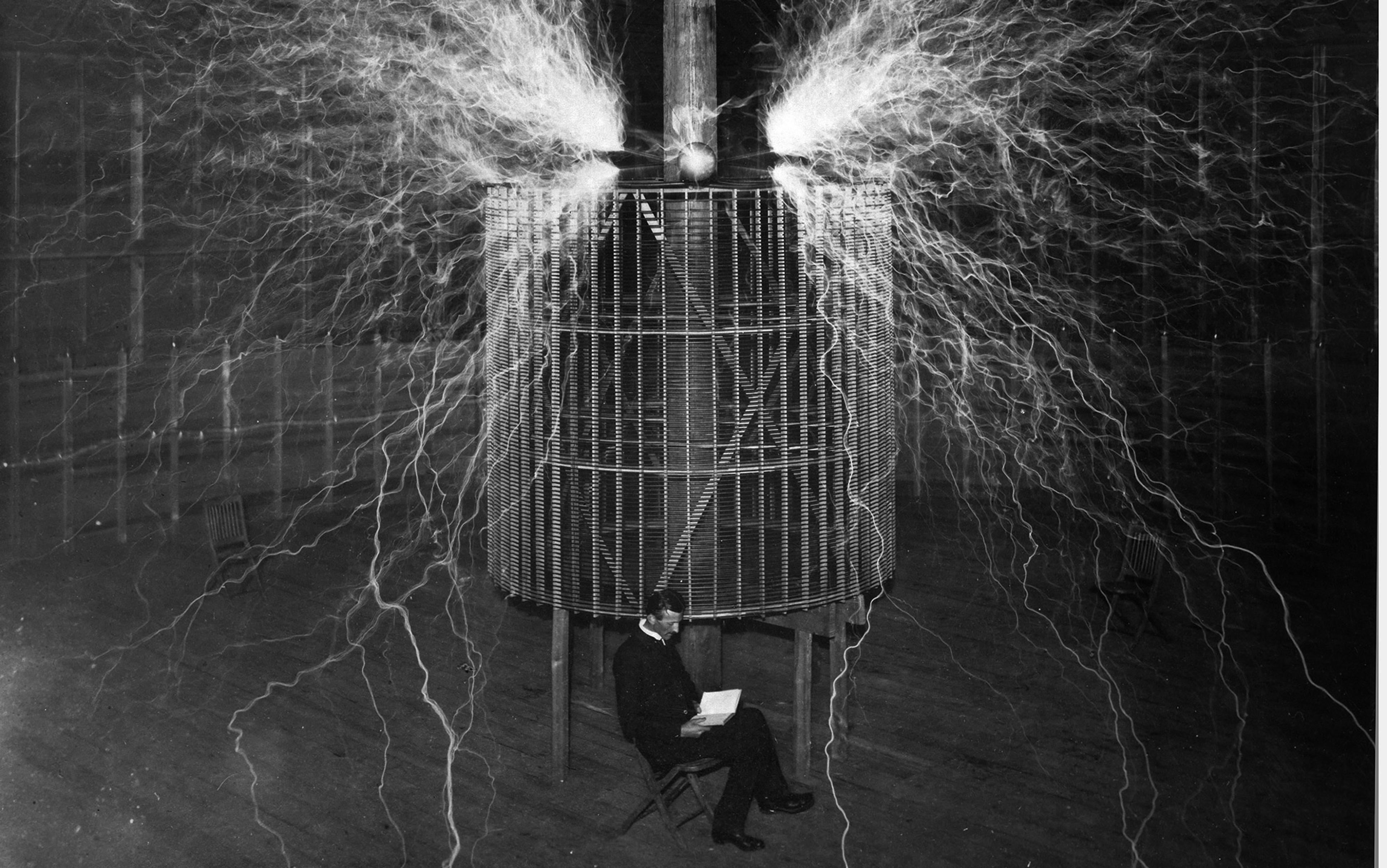

A single paper published in Nature, Cell, Science or other elite journals can set a scientist’s entire career on secure high ground. And a researcher with a grand string of such publication pearls, as well as prestigious grants, ascends to the scientific equivalent of a rock star. This leads to extreme competition for the precious few slots, and harms collaborative science. As Ferric Fang, the editor-in-chief of the journal Infection and Immunity, said: ‘In the end, what matters are the joys of discovery and the innumerable contributions both large and small that we all make through contact with other scientists.’

Science needs to be nudged back to its humble but glorious beginnings, when discovery itself was the means and the end. Retraction can then take its place in a pantheon of data-sharing, open commentary, proper citation of papers, willingness to correct mistakes, and the greater good of all.