I was in the last days of a family vacation in a house on a lake in northern Vermont when I got the news that Seamus Heaney had died. It was 30 August, not in the ‘dead of winter’, as when W B Yeats, his predecessor as greatest living Irish poet, had died, also at age 74. In his great poem on that loss, W H Auden had written ‘Let the Irish vessel lie/ Emptied of its poetry.’ Yeats died in January of 1939. Heaney was born in April of that year and, remarkably, the vessel was refilled. Now we await another elegist as great as Auden.

I was vacationing, away from cities, and had not really expected to have an internet connection — had, indeed, been looking forward to not having it — but wires go everywhere these days, and the will to cut oneself off voluntarily is weak. I was the first one awake. The hour was early morning, the lake was still misted over. I had started the coffee and was taking a few minutes to catch up on screen business. There was something from my poet-friend Peter. I noted the subject heading ‘Seamus Heaney at 74’, but thought nothing of it. No, that’s not quite true. I unthinkingly assumed this was news of some commemoration, a birthday salute — though I knew, we all did, that his birthday was in April, that he shared his date with Samuel Beckett. When I opened the email and saw that there was no message, just a link, I clicked. And then all at once I was awake and trying to take in what I was reading. Seamus Heaney was dead. Seamus was dead.

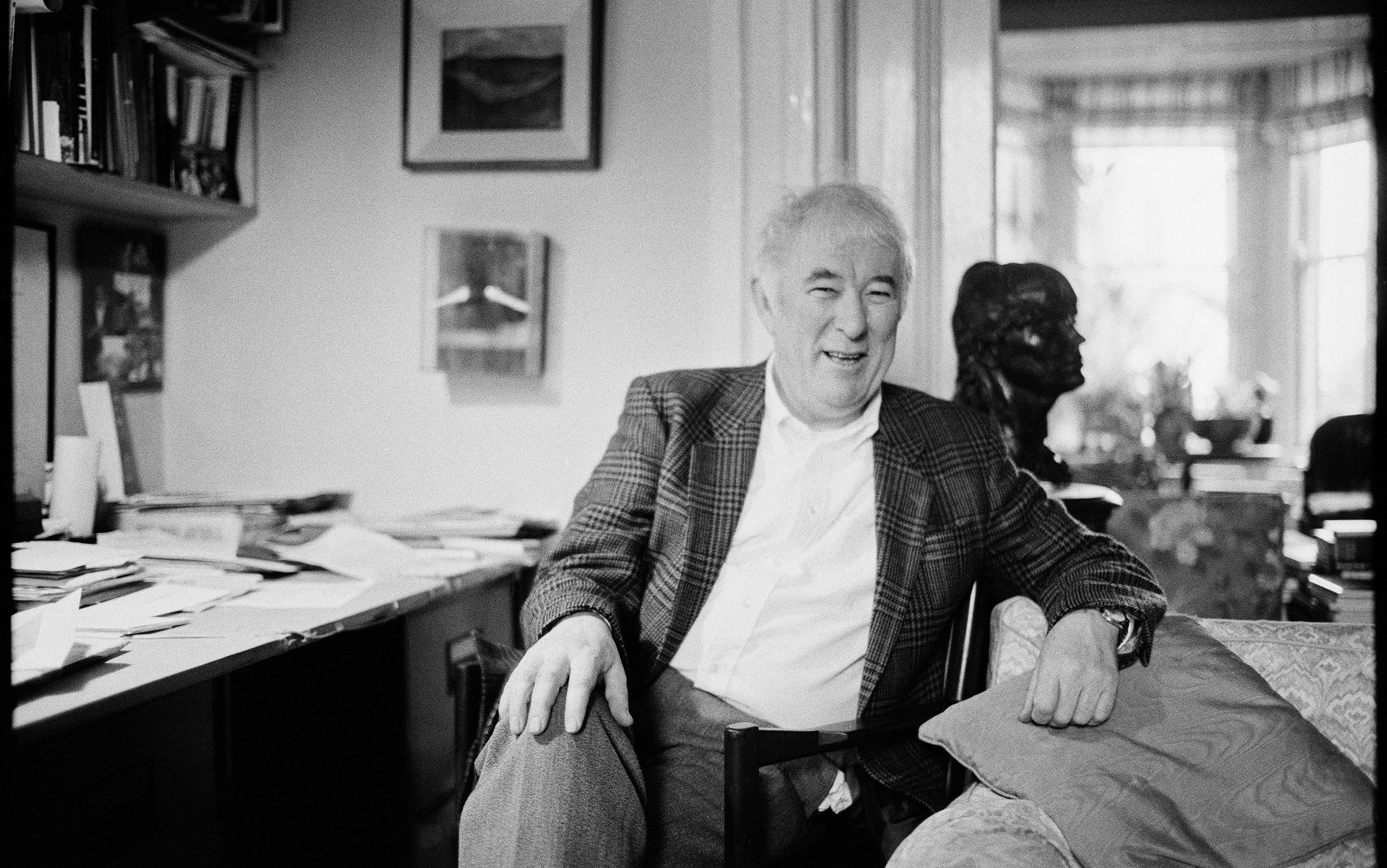

I use the first name because we were friends. Not best friends — he had his various true intimates — but real friends. That’s what I tell myself. We had met at a poetry reading in Cambridge back in the early 1980s, soon after he started his once-a-year teaching job at Harvard. He was approachable, easy to have a drink with, and soon enough a circle of friends had fastened around him. There were dinners, long evenings, at our house and other houses. Seamus, his wife Marie when she was over for a visit, poets of his acquaintance. It was all very gregarious — we were 30 years younger then. Later, after he had stopped teaching at Harvard, there were still visits, in Cambridge, in Dublin, more long evenings. But also less contact. I knew Seamus had had a stroke a few years ago. I’d seen him several times since and had noted its effects. A presence massively solid had been shaken. But the spirit was mighty and it was unthinkable that he would not go on and on.

‘Seamus Heaney at 74.’ I had not seen the poet-friend who’d sent the link for some months, but I remembered that the last time we’d spoken it had been about Seamus. Last winter I had been invited to the college where he teaches to give a talk — on reading in the age of the internet. I had paced up and down before a hall filled with undergraduates, voicing my sense of urgency while trying hard not to give off the antediluvian vibration that renders all such postulation ridiculous. I’m not sure if I managed it. Peter seemed to think it had gone well, that my scenarios of digital saturation had struck the necessary nerve. But we let the subject go. The next morning, before I drove back to Boston, we mainly talked about Seamus, our mutual friend. For it was Seamus who had decided decades ago, for whatever reason, that we ought to know one another. We talked much about his kindness and his canny intuitions. He was a person whom it feels good to talk about.

But now it was the end of summer, and Peter was sending the impossible news, and my first reaction, alongside complete disbelief, was not the grave sense of the loss of my friend, but something else, a feeling that was strangely collective. Auden wrote of the moment of Yeats’s death that ‘he became his admirers’, and I had the strongest feeling just then of what he meant. I conjured all at once, if this is possible, the idea, the emotional image, of all of those who knew and loved Seamus, or knew and loved his work — or both — and I felt inside the ghostly trace of a circuitry. That in this one moment all over the world, and of course most densely in Ireland, in Dublin, and most overwhelmingly on his own home ground in Sandymount, this same shock of incomprehension — not yet bereavement — was being registered. I pictured one person after another, dozens perhaps, and these were only the people who I knew who had a connection. Of course there were hundreds, many hundreds more.

When I drove down to the general store the next morning to get The New York Times and The Boston Globe, that sense was confirmed. There was massive front-page coverage everywhere — the biggest I’d ever seen for the death of a writer.

I had not thought until recently that these two occasions — my visiting Peter’s campus to talk about the transformations of the reading culture, and his later notifying me of Seamus’s death — belonged together in an essay, but I see now that they do. Not easily or obviously, not in tongue-and-groove fashion, but more broadly, thematically, with all the allowances of essayistic elasticity. If I pose for myself the two big questions that I am forever asking, that were, in effect, the basis of my talk — namely, what is the transformation that is taking place? And what is it that I fear the loss of? — then the connection starts to come clear.

It is dangerous, I know, to have a person stand for something, be ‘representative’ in the sense that the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson had it in 1850. That one individual could in any way ‘embody’ the spirit of a historical period seems archaic, as does the notion that a period could have a spirit. Our cultural mantra is plurality, complex polyvalence, and the intensifying deluge of information ensures more of the same. Character itself is a contested concept.

Yet when Heaney died in August, in the days and weeks that followed, there was a sense, throughout the literary world, but in the larger culture as well, that a singular and — I will risk the word — representative greatness had been taken from our midst. Many thousands of people were mourning not just the loss of a buoyant personality and an artist of rarest verbal gifts, but something more. Obituaries and reminiscences the world over testified to qualities Heaney was felt to stand for. Maybe this was a kind of wishful thinking, a matter of projection, yet in another way that’s beside the point. Our wishes and projections are real and powerfully telling; they are us.

If he was an etymologist, it was never as a scholar looking for derivations, but as a poet looking to expose the living pulses of the past through words

Heaney was seen as the man of place, as a sensibility tuned at once to the immediacies of the world around him — his poetry bristles with ‘thingness’, the felt presence of the real — and to the intimations of spirit, the idea that experience is charged with a higher, if not readily nameable, significance. He was at the same time a poet of profound historical imagination, alert not only to the ongoing factional struggles of his native Ireland and their roots in complex age-old division, but also to what might be called our tribal memory. Reading Heaney, we feel the truth of the French philosopher Simone Weil’s obvious but elusive assertion that ‘time is real’. It is, manifestly. Heaney wrote of bog people exhumed from the peat, but also of the ancient gods, their survival in epiphanic occasions of the spirit; he translated Sophocles and brought Beowulf into the context of the present, and did so through a prodigious feat of linguistic resuscitation.

Heaney fused in his work a power of unmediated attentiveness, of focus, and an ear attuned to the highly nuanced layerings of language. If he was an etymologist, it was never as a scholar looking for derivations, but as a poet looking to expose the living pulses of the past through words.

In the early poem ‘Personal Helicon’ (1966), Heaney describes himself as a child fascinated by the mysterious depths of wells. He writes: ‘I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells/Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss.’ And, later: ‘Others had echoes, gave back your own call/With a clean new music in it.’ He concludes:

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

The poem is a kind of credo, one of several in his first collection Death of a Naturalist (1966). Another such, deeply memorable — now canonical — is that book’s very first poem, ‘Digging’, in which he invokes the image of himself at his desk while his father works with a spade outside his window. The poet thinks of the years of work — field work — and exclaims: ‘By God, the old man could handle a spade/Just like his old man.’ Generations in a place, traditions going back. He will be the one to break the chain, admitting ‘I’ve no spade to follow men like them.’ But then adding: ‘Between my finger and my thumb/The squat pen rests./ I’ll dig with it.’

That verb ‘dig’ at first seems self-mocking, and maybe at the very outset of Heaney’s career, such an attitude was apt. But in the light of the decades of work that came after, the line can be read almost as prophecy. For what Heaney did was just that: he went down into the layers — of personal past, cultural past, tribal or mythic past, linguistic past — and he excavated. How much of this was by way of stubborn intent, and how much just a matter of disposition, is unknown. But in practice and in stance he set himself counter. In a world going swiftly neural and lateral, he stayed vertical, dug in. Not to strike a posture, however, or register a protest. But because, for him, imagination was primary — it was the source of meaning and making — and he knew that imagination, and its requirement of attention, cannot be sustained where the signals flash too distractingly.

These signals flash too distractingly everywhere now — their flashing, streaming, pulsing is the new norm, our common cognitive environment, and we are so completely wrapped in all of it that we can’t even see the extent. Unless — until — the moment of the outage. The shock of the sudden cessation. Which does sometimes happen: the wind snaps the great branch, the wet snow hauls down the whole support system. There, in the dead of winter, it quits on us.

We had a version of this here at home just two weeks ago. The box in the basement that feeds us our bundled services — internet, telephone, TV — went, in that beautiful 1950s locution, ‘on the fritz’. As it happened, our connections were down for five days. Five days during which we were all allowed to see, as in a woodcut where the background surface has been carved away, the clear outline of our dependence.

At first, there was outrage. This was impossible! That the system on which everything runs should have abruptly, absurdly, gone flat. I experienced an initial sense of impotence, trying this or that fix, always finding the same notification: no internet connection. It seemed to go against nature. At the very same time, though — magical thinking — I had the crazy irrational certainty that in a moment all would be well. Someone somewhere would throw a switch, mend a cable, whereupon the screen would light up, the phone would ring, and the accumulation of all those important messages would be there for the having.

I was just a man in a room. A man who, shuffling through his non-digital options, finds that he actually has quite a few

I had to ask myself what I imagined I was not seeing or responding to, why I was so antsy. When I thought about it rationally, there was not that much, not really. Far more, I realised, was the feeling of aborted potentiality, the great ‘What if?’ that underwrites so much of our screen obsession. It’s not so much about what’s there, but what might be. And when the connection is dead, that impending futurity fizzles down to nothing. Nothing might be.

But then time passed, another day, two days. The nature of the problem had been clarified and now there was just the long weekend to get through — and with the waning of that expectation of sudden restoration came a certain relaxation. Where formerly I obsessed about all the contact I might be missing, now I found myself also harking to the little freedoms that our situation brought. I could take a nap without any of the sub-threshold neural flutters about incoming this or imminent that. And though it was temporary, and illusory, I was not feeling in arrears to anything. I was just a man in a room. A man who, shuffling through his non-digital options, finds that he actually has quite a few.

Indeed, I realised that I had all of the things that had defined my days for so many years. I had my books, my music, what the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas called ‘my five and country senses’. The experience recalled to me a conversation I’d had years ago with an old friend. She had been telling me the story of her father, a long-term alcoholic, finally quitting the drink. ‘When you finally get past an addiction,’ she said, ‘you get back the self you had before.’ Is this regression? I don’t know what the experts would say, but I took her meaning that weekend.

This is not, however, another story of a primal recovery. After one more day of forced abstinence, we were back in business, all of us inclining forward in front of our laptops, harvesting our data. But something also had stuck. I took certain things further in my mind, I extrapolated, I projected the singular upon the collective. I contemplated this idea of regression. I found myself thinking of the novel by the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, The Lost Steps (1953), which chronicles a musicologist’s journey up the Orinoco river, how at every deeper penetration of the forest he discovers a native culture more isolated, more primitive, but also somehow more sensorily present, more vigorous. So very Romantic, so Rousseau-like (both Henri and Jean-Jacques), but a vision not to be utterly dismissed.

Not only does our digital living condition us profoundly, and by the stealthiest increments — so that with every new upgrade, every app, we are not only further empowered, but also more deeply reliant — but it also creates in us an estrangement, a sense of void. We gain in so many ways, pulling the info-world around us like a wire-woven cowl, creating planes of lateral linkage, giving and receiving messages — most of them tokens of ersatz connection — through a switchboard of disseminated impulses. We take the old limited one-self and refract it in every direction, and all around us people are doing the same, confirming us in our impulse. How easy it is to move in that direction — enabled flow — and how hard to move even slightly back the other way. If it’s so easy, it must be right.

But those gains are not without their sacrifices — though, as I observed, it gets harder and harder to see what those might be. Still, we do mark them, sometimes obliquely, by proxy. With, for example, the force of our sadness for a great man who has died, a poet with the rarest access to how things were, to the time and space of the old dispensation. T S Eliot’s ‘still point of the turning world’. We mourn the poet, but are we not also mourning the loss of what he had in his keeping? A language that mapped a way of living that served us for aeons, that we are now exchanging for other ways. We don’t regret our progress, not for the most part. But there is a tug. And in contemplating a poet such as Heaney, we understand what it is that still exerts that pull.

In Heaney, then, in the poetry and the image of the man, are distilled certain essential qualities — understandings, ways of relating to the world — that could be said to be under threat. His extraordinary physical immediacy comes through as unmediated, as opposed to the unquiet, fidgety, ever-impending now in which we live, his poems give us the felt, articulated sense of the past. Our sense of ambient ubiquity yields, in line after line, to evocations of place utterly granular, palpable in syllable and sound.

But enough now of my attributions and projections. Surely the point has been made. It only remains to wonder, how it was that the poet kept himself so focused, how he avoided being swept away by the essential, the indispensable gadgets? Did he really manage, living in the new millennium, to stay clear of the screens and circuits and the dissipating pull of it all? I don’t want to sanctify the man. It cannot have been easy.

I studied Seamus enough to know that he was a sly self-preservationist, wily in his pretences of technological ineptitude. To put it about that he felt too old-fashioned for the internet — that was a ploy. The man knew damn well that if he ever made himself available in that realm, he would have no time to call his own. Wisely, discreetly, he employed a proxy — an assistant who filtered messages sent to her name, and who responded on his behalf. What he did have, and used, apparently with great deftness, was a cellphone. I was shocked to learn this. A friend of his, a fellow Irish poet, confided to me that he and Seamus had great sport texting one another. Seamus, texting.

Indeed, the poet’s last communication was a text, according to his son. From the hospital bed, intending them for his wife, he dictated two words in Latin: noli timere. ‘Be not afraid.’ It was an extraordinary and heartening consolation, but also very much a private one. If there was a glimmer of something for the rest of us, it was maybe there in the way the timeline was folded back on itself — words from the old dead language flashing up on the screen not long before the end, or else the momentous transit.