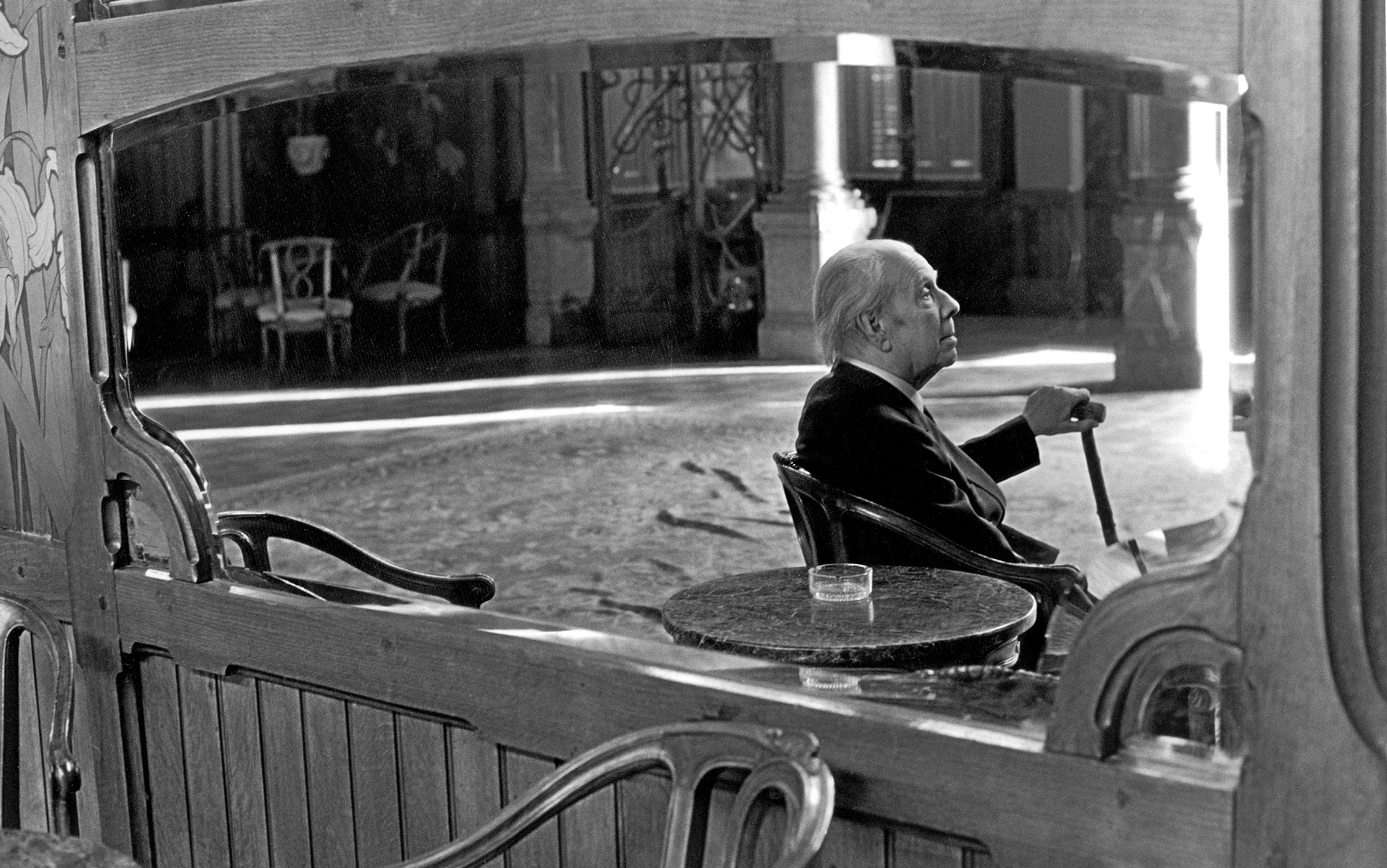

As history’s bloodiest war metastasised from Europe outward, two men – a world apart from each other, and coming from profoundly different disciplines – converged on one fundamentally similar idea. One of the men was a poet and short-fiction writer with middling success in his own country but virtually unknown outside its borders. The other man had already won the Nobel Prize for work he had done around 15 years earlier and would soon top the Allies’ most-wanted list for the work they suspected he had done in Germany’s unsuccessful atomic weapons programme.

But while Jorge Luis Borges knew nothing of the advances of quantum mechanics, and while Werner Heisenberg wouldn’t have encountered the work of a man among whose books was one that sold a mere 37 copies on the other side of the world in Argentina, around the year 1942 they were each obsessed with the same question: how does language both enable and interfere with our grasp of reality?

After the resounding failure of History of Eternity (1936), the book that sold only 37 copies in a year and garnered almost no critical attention, Borges slipped into a bog of depression. That book’s philosophical themes, however, continued to percolate and eventually emerged in an entirely different form in a series of stories called Artifices (1944). In that collection’s opening story, Borges describes a man who loses his ability to forget.

The man goes by the names Ireneo Funes. When the narrator of the story meets him, he is still a young man and known in his village for his quirky ability to tell the time whenever he is asked, although he never wears a watch. Two years later, upon his return to the town, the narrator learns that Funes has suffered an accident and is entirely paralysed, confined to his house on the edge of town. The narrator goes to visit him and finds him alone, smoking a cigarette on a cot in the dark. Astonished and saddened by Funes’s change of fortunes, the narrator is even more surprised to learn that the young man doesn’t perceive his condition as a disability, but as a gift. Funes believes the accident has endowed him with perfect memory.

The young man, who has never studied Latin, borrows a Latin dictionary and a copy of Pliny’s Naturalis historia from the narrator. He then greets him on his return by reciting, verbatim, the first paragraph of the 24th chapter of the tome’s seventh book: a passage about memory. However, though his ability to recall is astounding, Funes’s gift extends beyond mere memory. His immersion in the present is so profound, so perfect, that nothing to which his senses are exposed escapes his attention. In a poetic passage, Borges describes Funes’s abilities:

With one quick look, you and I perceive three wineglasses on a table; Funes perceived every grape that had been pressed into the wine and all the stalks and tendrils of its vineyard. He knew the forms of the clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memory with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once, or with the feathers of spray lifted by an oar on the Rio Negro on the eve of the Battle of Quebracho.

– from Collected Fictions (1998) by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley

While Funes insists that his abilities make his former life seem, in comparison, like that of a blind man, the narrator at once begins to glean the limitations of his condition. As Borges goes on to write:

[Funes] was able to reconstruct every dream, every daydream he had ever had. Two or three times he had reconstructed an entire day; he had never once erred or faltered, but each reconstruction had itself taken an entire day.

The man who perceives and remembers flawlessly the perception of everything around him is saturated in the immediacy of his memories. The very intensity with which he experiences the world interferes with that experience. For, if it takes an entire day to reconstruct the memory of a day, what has happened to that new day? And is it surprising that a man who experiences the world in such a way feels the need to wall himself off in a dark room to avoid being consumed by the converging floodwaters of memory and sense perception?

He lives in a world of individuals, and requires a representative system that honours that individuality

As Borges’s narrator starts to realise, the paradoxes of Funes’s affliction express themselves in his struggles with language. Emblematic of this struggle is how Funes deals with numbers. Rather than seeing them as elements of a general system, Funes feels the need to create an individual name and identity for every number. His numerical lexicon has, by the time of his conversation with Borges’s narrator, surpassed 24,000. As Borges, writes:

Instead of seven thousand thirteen (7013), he would say, for instance, ‘Máximo Pérez’; instead of seven thousand fourteen (7014), ‘the railroad’; other numbers were ‘Luis Melián Lafinur,’ ‘Olimar,’ ‘sulfur,’ ‘clubs,’ ‘the whale,’ ‘gas,’ ‘a stewpot,’ ‘Napoleon,’ ‘Agustín de Vedia.’ Instead of five hundred (500), he said ‘nine.’

Aside from being hilarious, the idea of Funes using one numeral to designate another captures the enormous disability that his superpower entails. Borges’s narrator notes this as well, pointing out that he tried to impress upon Funes that his system entirely misses the point of numbers, but to no avail. Funes isn’t capable of generalisation, of taking one sign as a stand-in for more than one thing. He lives in a world entirely populated by individuals, and requires a representative system that honours that individuality.

Funes requires the kind of language some early modern philosophers, such as John Locke, had postulated, one with a term for every being in existence. But, as the narrator goes on to speculate, if Locke rejected such a language for being so specific as to be useless, Funes rejects it because even that would be too general for him. This is because Funes is incapable of the basic function underlying and enabling all thinking – abstraction. Consequently, the way other humans use language inevitably dissatisfies him. The narrator tells us:

Not only was it difficult for him to see that the generic symbol ‘dog’ took in all the dissimilar individuals of all shapes and sizes, it irritated him that the ‘dog’ of three-fourteen in the afternoon, seen in profile, should be indicated by the same noun as the dog of three-fifteen, seen frontally. His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.

For Funes, human language is limited precisely by its slipperiness, and yet – and here is the brilliance and philosophical umph of Borges’s exploration – behind Funes’s claims for perfect perception and perfect recall, a paradox lurks. Funes would have us believe that each and every impression he has of the world is so overwhelmingly specific that our use of the same word for a dog in two different moments of spacetime is inadequate; he would have us believe he feels surprise each time he sees his own reflection.

But both his surprise and his irritation belie the very claim he is making; for, in order to be surprised at his own reflection, in order to be irritated by the generality of the word ‘dog’, Funes must himself also be able to generalise between the various impressions his face in the mirror or the dog at 3:14pm and at 3:15pm make. It is – and this is the whole point of Borges’s reflection – utterly impossible to be as immersed in the present as Funes claims to be and also to be aware enough of the generality of language to criticise it. Funes is having his proverbial cake – by experiencing the generality of language that allows it to identify different aspects of a thing – and eating it, too – by being so immersed in the present that such generality is ostensibly inconceivable.

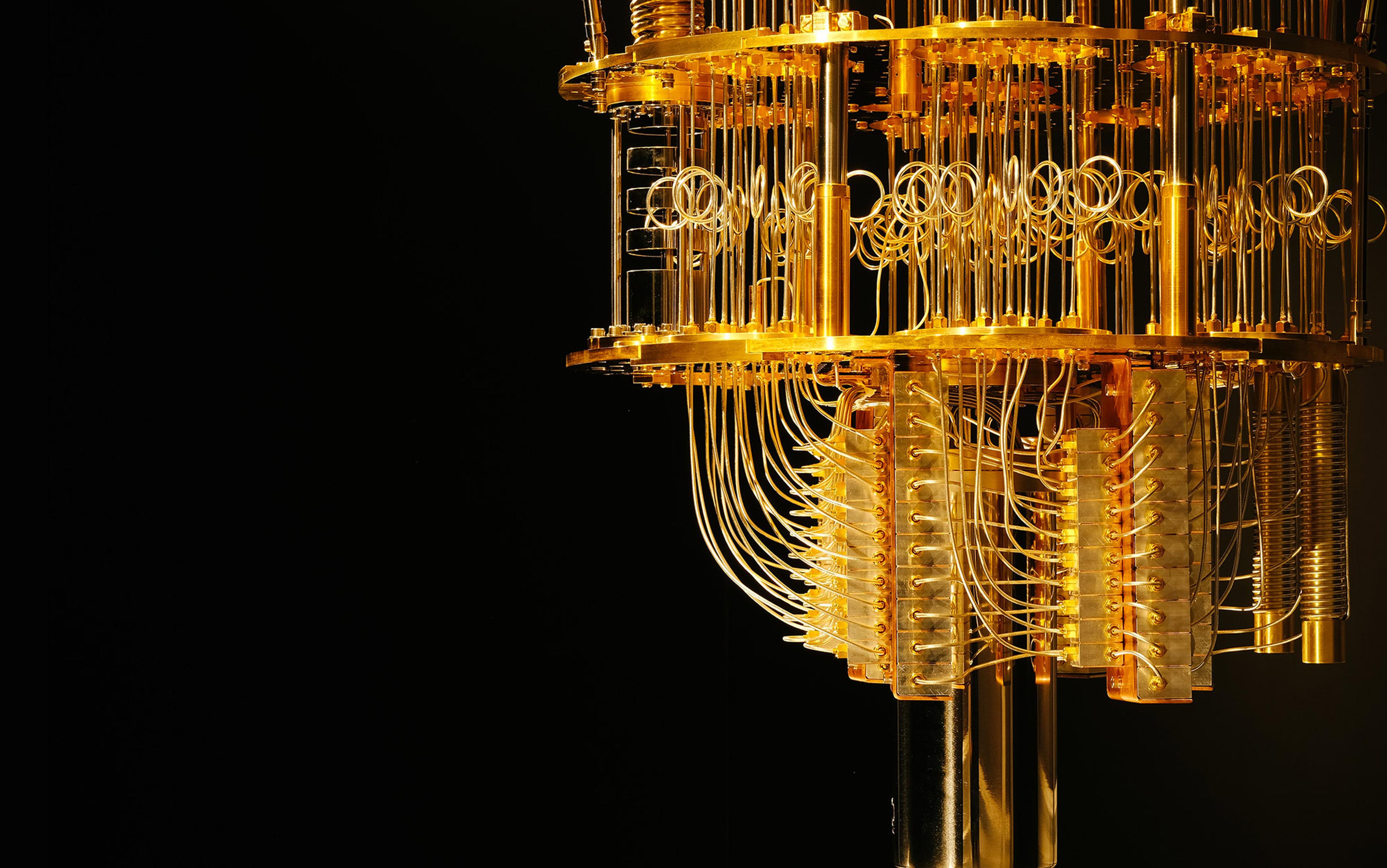

Meanwhile, as war raged around him, and as he worked to produce (or to hinder the production of, we may never know for sure) an atomic weapon for Germany, Heisenberg was secretly working on a philosophical book. The ‘Manuscript of 1942’ would be named not for the year it was published, which wouldn’t be until long after his death, but for the year he finished and circulated it among close friends. From that work, it would seem that what really interested Heisenberg during the time he was supposed to be working on Germany’s weapons programme was the mystery of our relation to and knowledge of reality. The issue, he believed, came down to language.

For Heisenberg, science translates reality into thought. Humans, in turn, require language in order to think. Language, however, depends on the same limitations that Heisenberg’s work from the 1920s showed held for our knowledge of nature. Language can home in on the world to a highly objective degree, where it becomes well defined and useful for scientists who study the natural world. But, when it is so focused and finely honed, language loses its other essential aspect, one we need in order to be able to think. Specifically, our words lose their ability to have meanings that change depending on their context.

Heisenberg calls the first kind of language use static, and the second dynamic. Humans use language in a variety of ways that span the spectrum between the mostly static and mostly dynamic. On one extreme, there are physicists, who strive to link their words as closely as possible to a single phenomenon. On the other side are poets, whose use of language depends on its ability to have multiple meanings. While scientists use the static quality of words so as to pin down observations under very specific conditions, they do so at a cost. As Heisenberg writes:

What is sacrificed in ‘static’ description is that infinitely complex association among words and concepts without which we would lack any sense at all that we have understood anything of the infinite abundance of reality.

Because of this trade-off, insofar as thinking about the world depends on coordinating both the static and dynamic aspects of language, ‘a complete and exact depiction of reality can never be achieved.’

Perceiving an object as it changes requires us to forget the minute difference between two different moments

We can see in Heisenberg’s theory of how language works parallels with Funes’s struggle. With Heisenberg, Borges’s poetic creation becomes the ideal example of an internal check on our knowledge, for the very perfection of Funes’s memory and the intensity of his perceptive abilities turn out to be a hindrance to his ability to understand or to distinguish perceptions from recollections. Imagine Funes as a physicist in his laboratory. He distinguishes every observation as sui generis, unrelated to anything else. His perfection of perception allows him to discern, in Borges’s words, ‘not only every leaf of every tree in every patch of forest, but every time he had perceived or imagined that leaf.’ Give him a cloud chamber, and he distinguishes not only each bead of condensation left by an errant electron, but the particle itself; and not only the particle, but each and every moment in the infinite sequence of moments that defines its trajectory.

But, of course, he cannot do this. He cannot because the very nature of perceiving an object, a particle, as it changes over time requires the perceiver to forget, ever so slightly, the minute difference between two different moments in spacetime. Without this minuscule blurring, this holding on to a moment of time so as to register its infinitesimal alteration in the next moment, all Funes the physicist would experience is an eternal now. A dog of 3:14pm, seen frontally, never to earn the name ‘dog’, never to be recognised, never to be observed at all.

Like Borges, as he strove to imagine what the world must be like for someone who perceives perfectly, what Heisenberg grasped was that to simultaneously observe a particle’s position and momentum with exactitude would require the observer’s co-presence with the particle in a single instant of spacetime, a requirement that contradicts the very possibility of observing anything at all. Not because of some spooky quality of the world of fundamental materials, but because the very nature of an observation is to synthesise at least two distinct moments in spacetime. As the great Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant had put it more than 100 years earlier, any observation requires distinguishing ‘the time in the succession of impressions on one another’. Observation undermines perfect being in the present because the observation injects space and time into what is being observed. A particle captured in a singular moment of spacetime is by definition unperceivable because, in Kant’s words, ‘as contained in one moment no representation can ever be anything other than absolute unity’ – an infinitely thin sliver of spacetime, with no before, no after, and hence nothing to observe.

Kant thought it was vital to understand this fundamental limit on human knowledge in order to ensure that science not fall into error. Heisenberg believed the same. As he writes in his manuscript, when science makes a new discovery:

[Its] sphere of validity appears to be pushed yet one more step into an impenetrable darkness that lies behind the ideas language is able to express. This feeling determines the direction of our thinking, but part of the essence of thinking is that the complex relationship it seeks to explore cannot be contained in words.

We need to be on the lookout for a barrier to our knowing, not one out there in the Universe but one we create when we impose our image of reality on the perpetually receding limit of our future discoveries. In Heisenberg’s words again:

The ability of human beings to understand is without limit. About the ultimate things we cannot speak.

Or, to put it another way, by presuming to speak of ultimate things, we put restraints on our ability to understand.

In the same year that Heisenberg finished and circulated his manuscript among a small circle of friends – to avoid the scrutiny of a regime that had labelled the brand of physics he was known for as ‘Jewish science’ and targeted him personally as a ‘white Jew’ – Borges published a curious essay in the magazine La Nación. The essay ostensibly reviewed the contributions made by John Wilkins, the 17th-century natural philosopher and co-founder of the Royal Society, to the search to create a language that would not suffer from the deficiencies and mutations that plague natural languages.

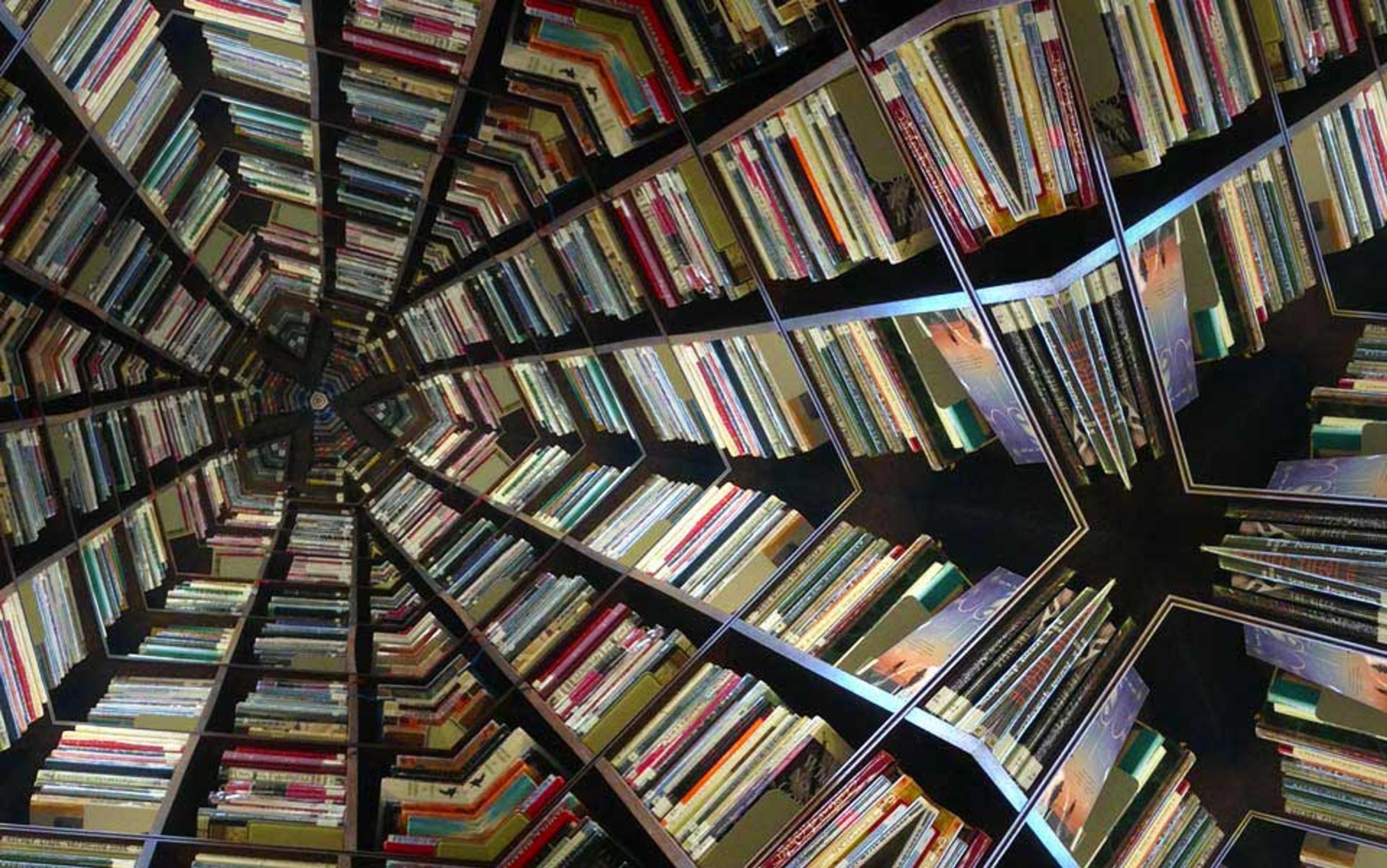

The essay’s most famous sentences come from its concluding paragraphs, in which Borges compares the redundancies and inconsistencies he sees in Wilkins’s rational language to a system of categorisation he claims to have found in ‘a certain Chinese encyclopaedia entitled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge’, in which:

the animals are divided into (a) those that belong to the Emperor, (b) embalmed ones, (c) those that are trained, (d) suckling pigs, (e) mermaids, (f) fabulous ones, (g) stray dogs, (h) those that are included in this classification, (i) those that tremble as if they were mad, (j) innumerable ones, (k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s hair brush, (l) others, (m) those that have just broken a flower vase, (n) those that resemble flies from a distance.

Michel Foucault memorably begins his book The Order of Things (1966) by recalling his reaction when first reading Borges’s list. But whereas Foucault’s reaction was astonishment – the alienating wonderment provoked by an entirely different, arbitrary and seemingly contradictory classification system – Borges’s fictive encyclopaedia is meant to undermine a confidence we tend to share with Wilkins, and one that his rational language is built on.

A language designed to account for everything that exists founders on the shoals of its own completeness

Communication is slippery because the words in natural languages are, in Ferdinand de Saussure’s assessment, unmotivated. Different words in different languages dissect the world in different ways. But a truly rational language would avoid such discomfort. The vicissitudes of translation would forever be banished. Wilkins aimed at a system of classification akin to the Linnaean taxonomy but which would apply to everything that can be expressed in language. Every letter in a word would be meaningful and add to its distinctness. As Borges explains it:

For example, de means element; deb, the first of the elements, fire; deba, a portion of the element of fire, a flame.

But far from rational, perfect communicability, Wilkins’s system devolves into a dumpster fire of contradictions, redundancies and tautologies. It turns out that a language designed to account for everything that exists founders on the shoals of its own completeness. Wilkins didn’t aim to produce a work of comedy, but his lists are every bit as absurd as those of the Celestial Emporium. The reason for this, however, has nothing to do with the choices Wilkins makes. Any similar attempt, Borges implies, would quickly rack up such inanities. For the very idea of a representational system that categorises being on a one-to-one level, like Locke’s abandoned hope or Funes’s ridiculous numerical grid, imports a false idea of reality: that it is out there, broken into bite-sized chunks, just waiting to be corresponded to. But, as Borges goes on to write:

[O]bviously there is no classification of the universe that is not arbitrary and conjectural. The reason is very simple: we do not know what the universe is.

More than that, he continues:

[W]e must suspect that there is no universe in the organic, unifying sense inherent in that ambitious word.

However, the Universe, in that organic, unifying sense, is what underlay generations of presuppositions regarding the nature of space and time, the independence of reality from our measurements of it, and the ability of science to know that reality down to its most intimate core. It was precisely such a universe – a universe in which a particle would have the decency to have both a position and momentum to be measured with perfect accuracy, the very hope and presumption of science – that Heisenberg’s discovery demolished.