In September 1961, Richard Feynman gave the first in a series of lectures on basic physics at the California Institute of Technology. At the start of the first day of class, he described the foundations of his subject to almost 200 aspiring scientists (and more than a few of his colleagues): ‘The principle of science, the definition, almost, is the following: The test of all knowledge is experiment.’ This, he declared, ‘is the sole judge of scientific “truth”.’

Over the next two years, Feynman distilled more than two centuries of knowledge into his lectures. He was a better physicist than he was either a mentor or a man (Feynman was wretched to women and disdainful of his students), yet he remains the greatest teacher most physicists never had. And though he taught his introductory course only once, the magisterial book that derived from it, The Feynman Lectures on Physics (1963-65), still cultivates physicists today.

When I was an aspiring physicist, decades later and more than half a continent away, I too appreciated the basics from The Feynman Lectures on Physics during my first year of college. But it was only during my final year that I began to understand what he had told the class about experiments on the first day. That fall, in a laboratory course required of all students majoring in physics, three experiments became the sole test of my knowledge, too.

With other students, I designed circuits to count flickers of light inside a flask. These were the flashes from a dense liquid struck by antiparticles, whose arrival among cosmic rays signalled the relativity of time and Albert Einstein’s equivalence of energy and substance. Next, we measured the speed of sound in a vat of helium as it cooled from a gas to a liquid. At two degrees above absolute zero, we witnessed helium molecules abruptly huddle into a quantum whole greater than its parts. This placid superfluid then transitioned into a fountain as the molecules charged from their confines, moved as if by collective will. Finally, we communicated all at once with billions upon billions of protons swarming in water. We nudged these particles into resonance, using a radio wave tuned to their spins, as one might excite children to twirl in unison with a song. We then listened for an echo, a collective response to our call, to glean their magnetic resonance – a technique physicians used to image the soft tissue in our aqueous bodies.

We were learning to be the authors of experiments, not just the readers. But even the simplest plots of physics were so bizarre that they were too difficult to recount in words. We learned that, to extract any sense from matter, we had to contrive intricate machines and derive byzantine equations.

Twice a week, after leaving the experiments in that shabby lab, I hustled across campus to study the opposite. In a neo-gothic hall, I learned how to tease meaning from experiments with the immaterial – with prose and the imagination. In a course required of all students in my second major, Spanish Literature, I read the most important works from 16th- and 17th-century Spain. And I entered a whole other world, far from the antiparticles and quantum wholes across the way.

Here, I learned how the anonymous author who wrote La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), The Life of Little Lázaro of Tormes, invented the picaresque form of storytelling through the adventures of an antihero, little Lázaro. This rogue appeared centuries before such characters came to dominate the shows on our screens. Next, we read Don Quixote (1605-15) and realised that its author, Miguel de Cervantes, had not only written the first modern novel, he had also frisked our modern notions of truth and reality. Cervantes had created a character who is more certain of the chivalrous world inside his head than of the actual world outside – the result is a comedy of self-contradiction so original it outwits our expectations even today. Finally, we discovered that, not long after the publication of Don Quixote, Tirso de Molina was the first author to stage the legend of Don Juan, in El Burlador de Sevilla y Convidado de Piedra (The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest). Molina used his dark comedy to reinvent the anti-romantic figure, satirising the still-impossible ideals of chastity and free will.

I loved those bygone tales. I related to their characters instinctively, even though I had never inhabited their worlds. They moved me. But no matter how authentic they seemed, how true to life, they would always remain figments, unlike the imperceptible particles I detected in the laboratory. I could never empathise with protons, electrons and other particles, but they remained more real than the complex protagonists of Spanish literature.

When I graduated, my two worlds could not have seemed more dissimilar. Fiction wielded an intimate imaginary. Physics plied the unrelatable real. I was not sure I would ever reconcile the two.

You almost certainly believe, as I did, that there is little overlap between the routines and aspirations of fiction writers and physicists. You are, as I was, almost certainly wrong. Both are the purveyors of real and imagined worlds. Both are interrogators of the intangible, posing some of our broodiest questions about existence. Both are persistent experimenters, putting human knowledge to the test.

There are surprisingly deep consonances between the experiments in physics and in fiction, particularly literature written in Spanish. Some of the greatest experiments in the Spanish language, which are some of the greatest experiments in any literature, were either undertaken by former physicists or leased from physical principles. These works, I eventually realised, may even help us understand what it means for experiments to be ‘the test of all knowledge’.

There is no singular method to experiments in the sciences. We do not observe superfluidity as we track ocean currents. Quantum field theory cannot be confirmed through field work. There are simply too many genres of science to generalise all its experiments.

That has never stopped people from trying. Scientists still enumerate a method that has anywhere from three to a dozen steps. Some philosophers generalise experiments further as ‘interventions’: each is a connection between some instrument and an object, visible or not, that humans wish to understand. In their accounting, an experiment is the intermediary between the physical world and human minds. It is the handmaiden to perceptions. At best, it is a programme for discovering ourselves and the impersonal world.

Novelists don’t merely gaze inward to create new forms. They look outward, too

That is not how most people understand experiments in fiction. But experiments in fiction defy simple characterisation as those in science do. There is no unique fictional mode, just as there is no method singular to science. Each experiment is novel, each novel an experiment.

During the 1980s, Gerald Prince, an eminent professor of French literature, did try to define ‘experimental fiction’. The words for ‘experiment’ in each of the Romance languages remain synonyms for the term’s original sense: an experience. But Prince immediately rejected this definition as too generic; surely every novelist wrote from experience. He also rejected the denotation, from Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, that an experiment is a test or a trial to demonstrate truth – experiments in fiction did more than put truth to the test. Prince even rejected the gimmicky literary experiments of postmodernism and the avant-garde, but he briefly entertained the notion that experiments in fiction could be like those in science. He thought especially of Émile Zola’s empiricism in The Experimental Novel (1880), and he weighed the rigorous work of Raymond Queneau and other writers and mathematicians who were members of the literary collective Oulipo. These authors, at least, adhered to some method, or ‘recipe’ as Prince called it.

But Prince eventually enumerated just three traits common to literary experiments. They pique through form or structure rather than plot. Their concerns are interior to the text, not exterior. They tease or twist language systematically. They are, in other words, self-referential, even recursive. In sum, they are exercises in manipulation and control.

These are not the only experiments that novelists undertake with fiction. Novelists do not merely gaze inward to create new forms or invent new ways of saying. They look outward, too. They direct their experiments toward the greater patterns of the world. They also stretch space and time, and quiz the substance of reality.

Novelists can experiment like physicists do, yet Feynman hinted that the inverse was also true. Scientific experiments required much more than rote method to derive knowledge. As he told his class at Caltech on the first day: ‘Also needed is imagination.’ Only by experimenting with the possibilities of the world could physicists make guesses about its ‘wonderful, simple, but very strange patterns’.

During my final semester of college, I proposed writing an honours thesis with a professor who was an expert on the mingling of reality and fiction in medieval Spanish texts. I was drawn to this mingling but wanted to research a more modern subject – one related to my other major. My professor asked if I might consider why Gabriel García Márquez set so many of the One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) inside a laboratory, the original site for his magical realism. I demurred. I wanted to do more than reinterpret a lab as the setting for fictional experiments.

I wanted, instead, to understand two Latin American writers who had also studied physics: Nicanor Parra and Ernesto Sábato. I wanted to alloy my two worlds, as I believed they had. My professor agreed to supervise this stubborn idea, but she further recommended the short fictions of Jorge Luis Borges, especially those that alluded to science. I would read Parra’s Poemas y Antipoemas (1954), Sábato’s El Túnel (1948) and Ficciones by Borges (1944).

Parra was born aside the Andes Mountains of central Chile in 1914. Although he wrote poetry as a young man, he would study physics and mathematics at university, both at home and abroad. Beginning in the late 1940s, while learning cosmology at the University of Oxford, Parra developed the irreverent style that would come to define his ‘antipoems’. His ironic works are laden with slang and infused with fantasy; they are a poetry for everyone, in any frame of reference. He would continue to pursue this style after returning to Chile, while teaching physics for 40 years.

A famous compatriot, Roberto Bolaño, once said that Parra writes ‘as if tomorrow he will be electrocuted’. There is a certain gallows humour to Parra’s poems. Angels are commanded to get run over by trains, the names of great loves are forgotten. His ‘Ode to Some Doves’ ridicules those peaceful birds, his poetic ‘Epitaph’ pokes fun at his own appearance. In ‘Self-Portrait’, Parra asks us to look upon him in his usual setting, the classroom. He is a professor of physics who has lost his voice droning on for 40 hours a week. His eyes are ruined, his hair scarce, his nose whitewashed with chalk. He inspires, he says, little more than shame. Gone are the beautiful ideals of his youth; he now hallucinates strange forms and hears unaccountable sounds. ‘Life makes no sense,’ he writes at the end of his collection of antipoems.

Sábato played with time and reality through the unrealities of love and obsession

Parra’s witty antipoems are to traditional poems what antimatter is to matter. In fact, Parra referred to his poems as particles: they are characterised by great energies and speeds because they are so quaint and weightless. Yet in his particulate poems:

The world is what it is

and not what a son-of-a-bitch named Einstein

says it is.

Sábato was born three years before Parra, on the flats of Argentina, and he, too, studied physics at home and abroad. In 1938, after completing a dissertation on his experiments with quantum mechanics, he left for the Institut du Radium, founded by Marie Curie in Paris. While experimenting there with radiation, he befriended Surrealists in cafés and began to paint and write. He escaped France during the war and, after studying cosmic rays in the United States, returned home to teach physics. He eventually left science to write a series of essays, Uno y el universo (1945), One and the Universe, before moving into a cabin to finish his first novel, El Túnel (The Tunnel), in 1948. The work was one of the first examples of existentialist fiction, what Jean-Paul Sartre would deem an ‘anti-novel’.

In El Túnel, Sábato played with time and reality through the unrealities of love and obsession. A painter named Juan Pablo Castel is consumed with a married woman, María, across overlapping timelines. He craves her and her inaccessible thoughts so thoroughly that, even after they are together, he invents a pretence to murder her. The story fragments as his mind does, drawing us into his tortured thoughts. Castel is mad with his inability to know María completely – mad with the inaccessibility of the world outside our minds:

[T]here were nightmares in which I was walking on the roof of a cathedral. I also remember waking up in my room in the dark with the horrifying sensation that the walls had expanded to infinity, and no matter how hard I ran, I would never reach them.

In my thesis, I suggested that the literary experiments of Parra and Sábato derived from their physics, but I was still unsure what exactly experiments were.

The previous summer, I had joined a lab to design experiments on the human perception of sound. Surrounded by racks of electronics, I learned to control the pitch and frequency of pure tones, to witness their precise, viridescent waves filling a fluorescent screen. I paid volunteers to don headphones and listen for the slightest variations between two white noises, played for one ear then the other. I verified that each listener had perfect pitch through a battery of tests in an anechoic room. I controlled for as many variables as I could. I still could not account for what the participants heard.

Each time the sound shifted from one ear to the other, the phase between the two white noises shifted randomly but imperceptibly. And, with each shift, listeners reported hearing an illusory pitch, a sound that never registered in our instruments. And all the participants perceived the same fictitious pitch. Although I could neither explain nor understand what the listeners heard, the result was exactly as predicted. I heard it, too.

It was a note from the illusive world inside our heads.

In physics, reality is not defined by what humans experience. Physicists know how delicate and contrary experiences can be. Reality is, instead, the substratum of objects with properties that are independent of our observations. It is the catalogue of physical possibilities beyond all humanity. Reality is the sturdy net beneath us as we inch the tightrope between birth and death.

Physics is often called a natural science, but that descriptor owes more to the discipline’s history than to current practice. Modern physicists often require as much artifice as fiction writers do. Just as novelists describe artificial worlds that help us understand the real, physicists also require artificial settings – their accelerators, detectors and models – to reveal scientific ‘truth’. When a physicist performs experiments with a cloud chamber, in which the tracks of invisible particles are revealed through a mist, they are using atmospheric conditions that have never been met under our skies.

Physicists do not study the world as they experience it. They do not seek to model what they might observe on a hike. Rather, they fashion simulacra then twist them in a lab. They try to exceed the natural, building clouds from possibilities rather than actualities, rendering wisps of the unseen. They, too, are novelists, crafting narratives of the real from their experiments.

In this library of innumerable possibilities, physicists continue to hunt for one true story

I mean this literally. Physicists even have their own genre of fiction, the thought experiment, in which they reimagine the world’s structure through prose. Erwin Schrödinger once imperilled a non-existent cat while trying to resolve possibilities into certainties. Werner Heisenberg peered through an imaginary microscope to set limits on the certainty of knowledge. Einstein narrated an impossible elevator ride to contemplate space and time.

In this way, physicists fret the nature of their measurements and cast doubts on facile notions of realism. Some quantum physicists go even further. They deny the existence of objects with definite properties, they deny the sturdy net beneath the tightrope we walk between life and death. Without interventions, without experiments in laboratories, the quantum world thus consists of little more than possibilities.

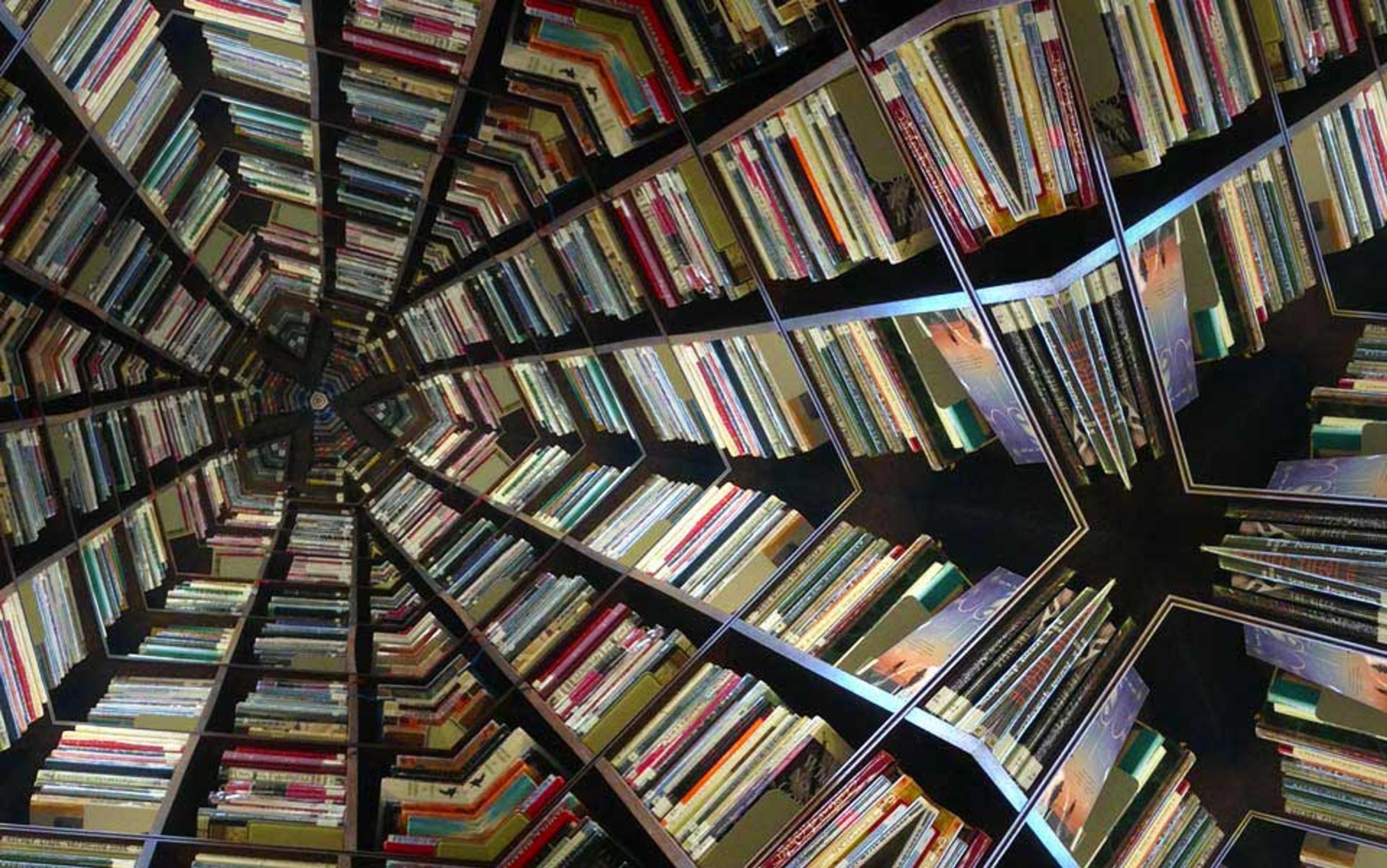

Quantum physicists and string theorists have further liberated their equations from a strict realism by crafting the fictions of other worlds. They have found a space for every story, impossible or not, inside the idea of a multiverse. But in this library of innumerable possibilities, physicists continue to hunt for one true story: a sole account of our reality.

The French writer Stendhal claimed in The Red and the Black (1830) that ‘a novel is a mirror carried along a high road’, which reflects the world as we observe it. He neglected the funhouse inside our heads, the surreal physics of experience and the imaginative limitlessness of the multiverse.

Novelists, too, manipulate imagined worlds and refract our reality through others unlike it. They prolong or compress events, they bridge time and space as wormholes might. They entangle individuals across vast distances, treating them as if they were fundamental particles. They deny the world is merely as we perceive it. The properties of such fictional worlds are not always circumscribed. They can shift, based on the whims and interactions of objects and characters – like the properties of objects in quantum mechanics.

In other words, each novel abides by its own laws, as does each world in the multiverse.

In physics, we play with what is feasible, regardless of how unimaginable it might be. In fiction, we play with the impossible, however real it seems. I wondered where the two might meet.

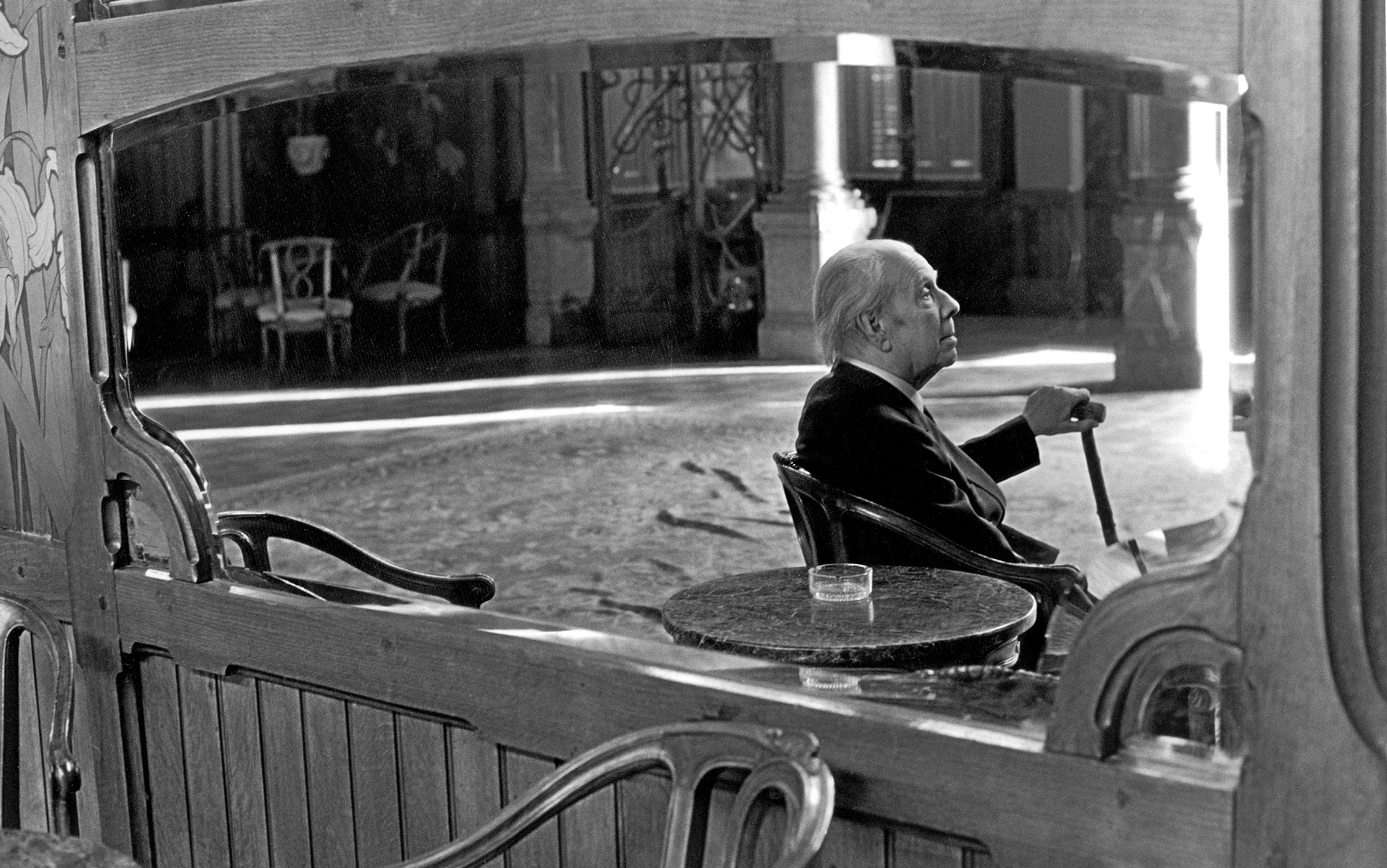

While I scuffled to find the physics in texts by Parra and Sábato, I read Ficciones by Borges. This collection of short stories is one of the most bountiful works of the 20th century. In each tale, Borges detailed fantastic impossibilities, stretching characters and environments beyond their temporal, spatial or psychological limits. There were labyrinths of every possible book, a man weighted with perfect memories, a writer who reproduced the novel Don Quixote, word for word, after immersing himself in its world.

I spent my evenings more baffled by these experiments than by the literary works of those former physicists, Parra and Sábato. Borges’s stories were even more confounding than my problem sets in quantum mechanics. In a page or two, frequently less, Borges could elicit paradoxes of time, space and reality that I might spend a lifetime misunderstanding.

I was not the only physicist under his sway. Sábato, too, had read Ficciones, after he quit physics for fiction. He had even borrowed the idea of overlapping timelines from Borges for El Túnel. Although Sábato taught relativity, Borges introduced him to fictional modes of time.

In my undergraduate ignorance, I translated Ficciones into English, not knowing other translations existed, not wanting to know because I wanted Borges to myself. I unravelled the short fictions of Borges, learning how he rarefied his prose – through unnatural infinities and impossibilities passed off as real. I still lost myself in his mirrors, labyrinths and curvatures of space and time.

Through this story, Borges had prefigured the Many-Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics

Through his work, I entered ‘La biblioteca de Babel’ (1941), ‘The Library of Babel’, in which Borges shelved all the possible texts in every language. The sum was not infinite as described; I calculated the number to be far greater than all the possible atoms in the Universe, yet finite. I later navigated a map as large as the world, a perfect representation of its terrain, in the single-paragraph story ‘Del rigor en la ciencia’ (1946), ‘On Exactitude in Science’. The story begins:

… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.

I even walked ‘El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan’ (1941), ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’, a story in which a writer does not have to choose among the countless alternatives for his protagonist. Instead, he writes them all, at every moment, and the character lives them all. At each subsequent moment, still more paths open to the protagonist. She inhabits the everywhere all at once. Through this story, Borges had prefigured the Many-Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, which the American physicist Hugh Everett proposed in his doctoral thesis in 1957. When the Argentine physicist Alberto Rojo later asked Borges about this foreshadowing, the author chuckled: ‘How imaginative are physicists!’

I read every Borges story I could, revelling especially in the dreamy fables of El Hacedor (1960), The Maker. At the time, I lived next door to a philosophy student from Mexico who said that, if I liked forking paths, if I liked authors who experimented with reality, I would love Rayuela (1963) by Julio Cortázar, later translated into English as Hopscotch.

Borges and Cortázar were not only compatriots; Borges inspired the younger writer and had published one of his first stories. From the start, they shared the concerns of most experimenters: reality, space and time.

As Cortázar noted in the ‘Table of Instructions’ to his novel, Hopscotch was not one book but many. There were dislocations in space and time, between Paris and Argentina, but the reader was also asked to choose her own adventure, hopping among chapters or following a variation Córtazar had chalked out. Sequence and chronology, causality and locality, need not exist in fiction. Each reader built their own reality, made their own rules. They, too, could explore every possibility for the characters, as Borges described.

In a lecture that Cortázar gave about fictional time while visiting Berkeley in 1980, he would admit his ignorance of relativity, yet he insisted that the elasticity of space and time was the source of the fantastic in all stories. Afterward, a student asked about his references to Heisenberg in Hopscotch. Cortázar explained that, while living in Paris, he had read about the Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in the science supplement to Le Monde. When he learned that physicists reasoned with the fundamental limits to their knowledge, he was dumbstruck. He told the student: ‘[I]t’s exactly the same process that occurs in certain literature and poetry: just when you reach the limits of expression.’

Uncertainty not only motivated fiction, fiction was the greatest uncertainty. It was the beautiful unknowing that remained whenever we tried to know the physical world. It was what would always remain after our guesses about the ‘wonderful, simple, but very strange patterns’ behind reality. Fiction, in other words, was the sublime complement to science, the other experiments we would need to understand the world.

Sábato once complained: ‘Given my scientific training, no one thought it possible that I might dedicate myself seriously to literature … How was I to defend myself when my best antecedents were in the future?’

His greatest antecedent to come – the true heir to Parra, the beneficiary of Borges and Cortázar – was and would be Agustín Fernández Mallo, a Spanish physicist who inspired a generation of novelists, much as Hopscotch lit one of the matches that ignited what critics later called the ‘boom’ in Latin American literature.

During the mid-1980s, while Mallo was studying physics at the University of Santiago de Compostela, in the north of Spain, a classmate handed him a book with a Möbius strip on its cover: El Hacedor by Borges. Reading this book of poetic impressions, Mallo thought Borges had captured the ineffable logic of physics within fiction; he had written the literary complement to science, the anti-science.

Whenever matter and antimatter meet, they transform into energy and light. Mallo thereafter would write poems alongside the equations in his notebooks, and the two became one. Both compressed elegance into something far-reaching, albeit obscure.

Mallo wanted a new experiment, a scientific poetry equal to humanity

After Mallo graduated, he moved to Palma de Mallorca where, for nearly two decades, he wielded beams of particles against tumours in a hospital basement. During his time underground, he wrote poetic equations and eventually released them to the world in four collections.

Literature had long meddled with time and reality, as relativity and quantum mechanics did. But those sciences prevailed on inhuman scales, the minuscule and the immense. Mallo wanted a new experiment, a scientific poetry equal to humanity. He wanted to mingle the impossible with the real.

In 2003, an editor asked Mallo to explain the relationship between literature and physics. Mallo outlined a theory in his book of essays Postpoesia: Hacia un nuevo paradigma (2009), or Postpoetry: Toward a New Paradigm. His poetry was ‘the next logical step in the line of parallelisms that Nicanor Parra established when he equated poetry up to the 19th century with the Newtonian physics and vanguard poetry with the relativistic and quantum physics of the early 20th century’ (my translation). Mallo was writing a postpoetry built from the patterns and chaos of complex systems rather than the mechanics of inhuman particles.

Literature could be as real and indeterministic as the weather. It could be a semantic web of intimate but random associations, between disparate objects and characters, from real and imagined sources. Order could arise from disorder. A text could be a constellation, a smattering of stars in whose links people located meaning. It could become a superfluid charging from its confines.

During the summer of 2004, Mallo undertook his next experiment: a novel. In a newspaper, he had read an article about a cottonwood tree that shaded the loneliest road in Nevada, where people hung their shoes as an impromptu display of humanity in the desert. Around the same time, he found a quote by W B Yeats printed on a sugar packet, which reminded him of a punk song, about a chocolate-hazelnut spread, ‘Nocilla, ¡Qué merendilla!’ (‘Nocilla, what a snack!’) Convalescing from a broken hip in Thailand, these seemingly unrelated events propelled him into his first novel, Nocilla Dream (2006).

Mallo explained afterward: ‘[S]ome stories and characters have been taken directly from this “collective fiction” we communally refer to as “reality”.’ He linked vignettes about love and physics, about salmon factories, micro-nations, manhole covers, sex workers, and airports, with vague interrelations between characters and scenes. There was also self-reference – a character expounding a theory of literature identical to his own. The character reads ‘On Exactitude in Science’ by Borges every day at noon. Mallo was trying to map the entire world.

After three months, Mallo awoke from his Nocilla Dream. Weeks later, he started a second novel, Nocilla Experience (2008). Months after that, he wrote a third, Nocilla Lab (2010). In the finale to his trilogy, there is a resounding cameo, in graphic form, from Enrique Vila-Matas, the Spanish writer who once asked but could not answer: ‘Does reality really exist?’

In an endnote, about an echo of mathematics from Bolaño’s work in his own, Mallo would describe ‘the hidden threads of a literature that is beyond our control’. In his prose, those threads are thick. Strange parallels and repetitions are so frequent, one is tempted to map them, to represent the world of their making. That would be impossible. Its map would be bigger than the world.

He, too, heard a note from the illusive world inside our heads

Mallo quit physics thereafter to focus on literary experiments. In 2018, he published the novel Trilogía de la Guerra (translated as The Things We’ve Seen). The former physicist still hunted the interstices between the random and the surreal, a space he believed we all inhabited on the internet. We each read and create more fictions every day, it seemed, in the unreality we curate online than have ever existed.

In the first part of his second trilogy, Mallo follows an author who creates a residency on the abandoned island of San Simón before he begins to hear sounds he cannot account for. The author realises ‘the ringing in my ears had nothing to do with literature, was not a mirror for anything or a representation either, it was just a thing that was happening.’ He, too, heard a note from the illusive world inside our heads.

Other writers have also turned to physics in listening for this sound. Lina Meruane wrote an elegiac novel, Sistema nervioso (2018), or Nervous System, about black holes, family, and the gravity of the past. Jorge Volpi wrote a bestseller about the nature of truth and lies, En busca de Klingsor (1999), or In Search of Klingsor, told through the life of a physicist who resembles Heisenberg. Volpi even has a forthcoming book about the nature of reality in fiction and science. Benjamín Labatut has written several renowned novels about real physicists. These are closer to autobiographies, however, with glosses of well-trodden physics and slight fabrications, rather than heady experiments. None of these authors toys with reality as fluently as Mallo does.

‘The phrase “science fiction” is superfluous,’ Mallo once wrote, ‘because all science is fiction.’ His novels are, indeed, experiments to corroborate his theory of fictional complexity, a map of our world alongside every other, impossible or not. He blends fiction and science, the unreal with reality, the possible with the impossible, to understand all that it means to be human. His prose is a maze of funhouse mirrors, in which we may see ourselves or get lost.

At its worst, Mallo’s fiction resembles a conspiracist’s pegboard, where the associations between pushpins are nothing more than twine. At its best, his fictions cohere to a novel physics. They are a magnetic resonance, what physicists developed to peer inside living bodies, an echo of what lies hidden within.

The goal of physics is to understand the Universe at every scale, to know the vast but finite potential of all that we and our instruments may observe. The method of physics is to contort what is materially possible until we can shape it no more.

To know the world is to enumerate its possibilities. Physics thus demarcates the impossible, the infinite potential of universes not our own.

Fiction is our laboratory for the impossibilities that exceed our Universe, the infinity that casts limited reality in greater relief. Such impossibilities are also of the world because they are within us, because they move us, because they embolden or cower us. We never experience them directly, not really, not physically, but they enlarge humanity nonetheless. We may be confined by the possible, but we are citizens of the unreal.

Physics asks simple questions: it asks the possible. Fiction asks the hardest from us, the impossible. To know the world, we need both.

Experimentation, in both physics and fiction, is the asking of questions. It is not, however, the answering. No experiment can decide knowledge once and for all. Uncertainty always remains. There can be, in other words, no end to our experiments, no end to our imaginations, in either fiction or physics.