Since the dawn of anthropology, sociology and psychology, religion has been an object of fascination. Founding figures such as Sigmund Freud, Émile Durkheim and Max Weber all attempted to dissect it, taxonomise it, and explore its psychological and social functions. And long before the advent of the modern social sciences, philosophers such as Xenophanes, Lucretius, David Hume and Ludwig Feuerbach have pondered the origins of religion.

In the century since the founding of the social sciences, interest in religion has not waned – but confidence in grand theorising about it has. Few would now endorse Freud’s insistence that the origins of religion are entwined with Oedipal sexual desires towards mothers. Weber’s linkage of a Protestant work ethic and the origins of capitalism might remain influential, but his broader comparisons between the religion and culture of the occidental and oriental worlds are now rightly regarded as historically inaccurate and deeply Euro-centric.

Today, such sweeping claims about religion are looked upon skeptically, and a circumscribed relativism has instead become the norm. However, a new empirical approach to examining religion – dubbed the cognitive science of religion (CSR) – has recently perturbed the ghosts of theoretical grandeur by offering explanations for religious beliefs and practices that are informed by theories of evolution and therefore involve cognitive processes thought to be prevalent, if not universal, among human beings.

This approach, like its Victorian predecessors, offers the possibility of discovering universal commonalities among the many idiosyncracies in religious concepts, beliefs and practices found across history and culture. But unlike previous efforts, modern researchers largely eschew any attempt to provide a single monocausal explanation for religion, arguing that to do so is as meaningless as searching for a single explanation for art or science. These categories are just too broad for such an analysis. Instead, as the cognitive anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse at the University of Oxford puts it, a scientific study of religion must begin by ‘fractionating’ the concept of religion, breaking down the category into specific features that can be individually explored and explained, such as the belief in moralistic High Gods or participation in collective rituals.

For critics of the cognitive science of religion, this approach repeats the mistakes of the old grand theorists, just dressed up in trendy theoretical garb. The charge is that researchers are guilty of reifying the concept of religion as a universal, an ethnocentric approach that fails to appreciate the cultural diversity of the real world. Perhaps ironically, it is scholars in the Study of Religions discipline that now express the most skepticism about the usefulness of the term ‘religion’. They argue that it is inextricably Western and therefore loaded with assumptions related to the Abrahamic religious institutions that dominate in the West. For instance, the religious studies scholar Russell McCutcheon at the University of Alabama argues in Manufacturing Religion (1997) that scholars treating religion as a natural category have produced analyses that are ‘ahistorical, apolitical [and] fetishised’.

There is much that is valid in such critiques. It is important to highlight the tendency of North American and European scholars to associate religion with the endorsement of professed beliefs, regular participation in religious services, hierarchical institutions and exclusive membership. All of these are features of Abrahamic traditions, but none are essential to religious belief and practice worldwide.

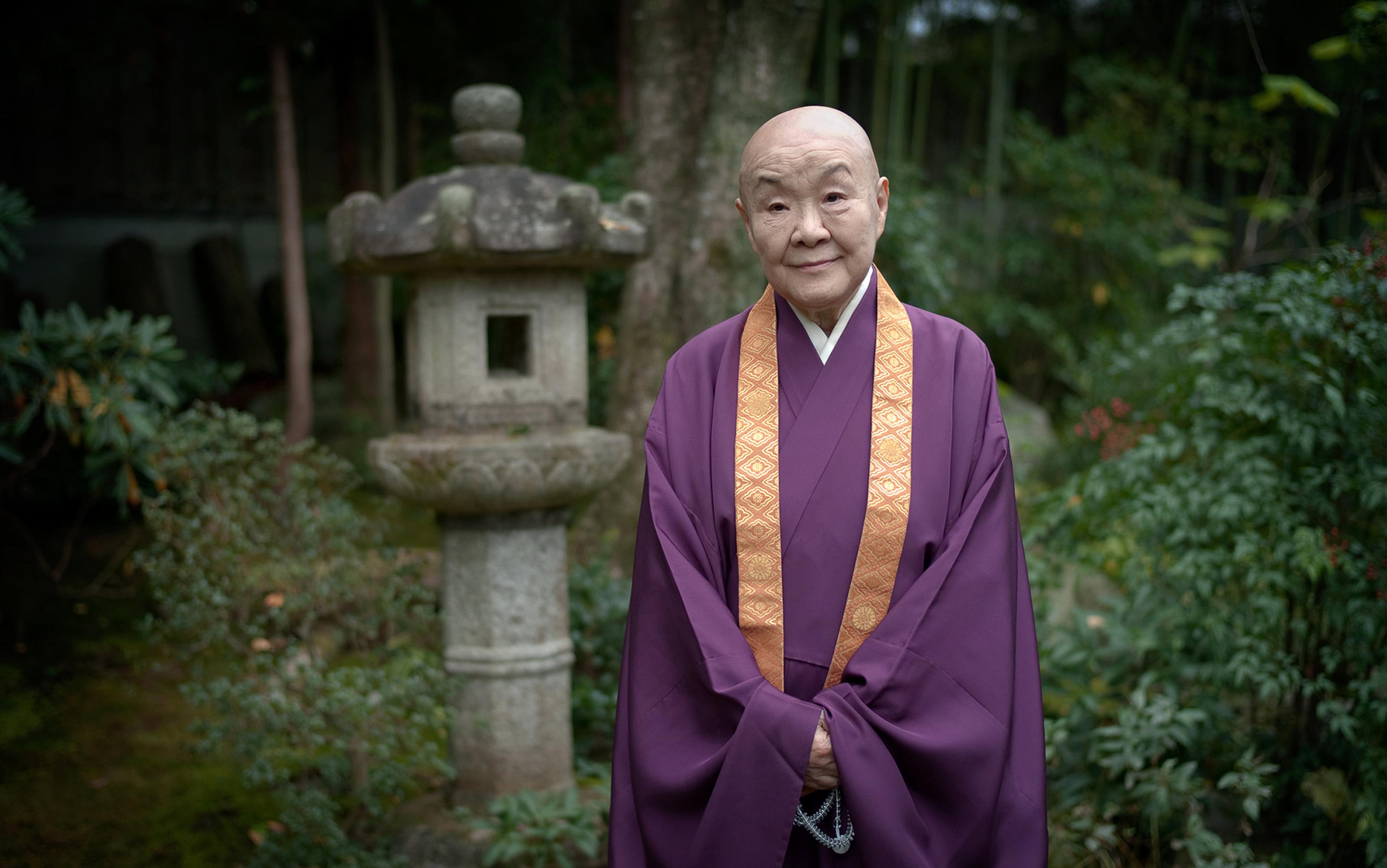

To demonstrate the limitations with the dominant Western concepts of religion, we must examine religion in a non-Western context; for example, in Japan, where I have lived for the past four years, conducting research on collective rituals and bonding. The vast majority of the Japanese population profess to have no strong religious beliefs, and there are few who regularly attend religious services. Regardless, many people happily partake in events and festivals arranged by multiple religious traditions. Indeed for many Japanese, the decision to marry in a Shinto or a Christian ceremony is not made according to religious beliefs but instead by the bride’s preference for wearing a traditional kimono or a white wedding gown (my own wedding experience in Japan involved both).

So is Japan just a non-religious society, like many surveys and some scholars claim? Or do we instead need to broaden our assumptions about what, in fact, constitutes religion?

As snow falls in the small town of Kikonai in northern Japan, a crowd gathers in the courtyard of a Shinto shrine. They are focused on the entrance of the shrine building, which is nestled picturesquely against the side of a mountain. Soon, four stone-faced young men emerge, standing with their arms folded across their chests. In defiance of the cold they are naked save for bright white loin cloths and thin cloth hats. They bite down on rolled-up pieces of cloth to prevent their teeth from chattering. After a pause, the men march down the stone steps of the shrine and climb onto a raised platform of straw. Facing the crowd, each takes turns kneeling, while the most senior of their group launches freezing water against their exposed backs.

The procedure is repeated three times, and for the final bout, water is slowly trickled onto their heads. After the sequence is complete, the men silently ascend back into the shrine building, steam rising from their flushed red backs. But this is not the end for them: they will return in just over two hours to begin the entire ordeal again, and this pattern will repeat every few hours for two days. Each performer has also pledged to repeat the two-day performance for four consecutive years, a promise that nobody in the 150-year history of the event has ever broken.

This feat of endurance is part of a Shinto water-purification ritual known as a misogi and is the central performance of a popular local festival in Kikonai. This particular event is unusual for the severity of the ritual performance involved but in most other respects it is entirely typical of the kinds of festival celebrations (called matsuri) found throughout Japan. Famous matsuri in large cities can attract millions of onlookers, and in remote villages these local festivals are among the most important community events of the year.

Are these matsuri merely community and cultural events – or are they specifically religious? Such an interpretation relies on erecting an artificial barrier between culture and religion, and also ignores a host of inconvenient facts. Most matsuri are performed in shrines or temples, they are organised by priests and affiliated volunteers, involve religious symbolism and devotional prayers, and rely on theological or metaphysical concepts such as purification. There are also straightforwardly secular rituals in Japan, such as the Yosakoi Soran dance festivals in which teams compete using choreographed dances, and this makes the religiosity of misogi matsuri and similar festivals that much more salient. In what sense, then, is Japan non-religious, if such intense religious rituals are part of its cultural fabric?

The two dominant religious traditions in Japan are Shintoism, an indigenous religion focused on deities or spirits called kami, and Buddhism, which spread to Japan from Korea and China roughly 1,500 years ago. Both traditions are involved with matsuri since most festivals are associated with specific shrines or temples and are timed to coincide with religious holidays, such as Obon (a Buddhist festival honouring ancestors) and Shōgatsu (New Year celebrations). Nevertheless, it is also true that few matsuri attendees are aware of the doctrinal details, including the particular deities that an event is dedicated towards. Despite the popularity of religious festivals and the prevalence of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples throughout Japan, is it accurate to characterise Japan as a secular country with little interest in religion?

Large-scale cross-cultural surveys seem to support this. For example, in the 2010-2014 wave of the World Values survey, conducted across 61 countries, 87.1 per cent of Japanese respondents stated that they were ‘not a member’ of a church or religious organisation, and only 20.9 per cent self-identified themselves as ‘religious’, independent of their attendance at religious services. Those results ranked Japan as the second least religious country in the world, behind only mainland China and Hong Kong.

a Japanese person can go to a Shinto shrine to receive blessings as a young child, get married in a Christian service, and eventually have a Buddhist funeral

This was not an isolated result. Similar patterns have been replicated across other surveys. WinGallup’s 2014 End of Year survey, for instance, found that only 13 per cent of Japanese respondents indicated they were religious, and in an online survey I conducted just last year, from more than 1,000 Japanese respondents, only 10 per cent self-identified as religious. Such results seem to provide strong support for claims that Japan is a non-religious country. The reality, however, is more complex.

In contrast to the figures just stated, the most recent official statistics from the Japanese government’s Statistical Yearbook report that there is an abundance of ‘religious organisations’ registered in Japan, including 81,097 Shinto shrines and 75,922 Buddhist temples. The figures also indicate that approximately 72 per cent of the Japanese population are adherents to Shintoism, while 68 per cent are followers of Buddhism. Though the combined total of these two figures is greater than 100 per cent, this is not a calculation error. The figures show that religious affiliation is not a mutually exclusive affair in Japan. Many people are being counted twice: once as a Shinto adherent and once as a Buddhist adherent. Japanese people are highly syncretic, incorporating and blending various elements from each tradition together.

Ian Reader, a sociologist and professor emeritus at the University of Manchester, has spent decades researching religion in Japan. He notes that the long-term co-existence of Shintoism and Buddhism has resulted in a complementary ‘division of labour’ among the prominent religious traditions. Shinto celebrations are broadly used at the beginning of life and for seasonal celebration. Buddhism is primarily concerned with death and ancestor rites. Meanwhile, Christianity, to which only 1-2 per cent of the population adheres, is associated with weddings. As a result, it is entirely unremarkable for a Japanese person to be taken to a Shinto shrine to receive blessings as a young child, get married in a Christian service, and eventually have a Buddhist funeral. Religious pluralism is not merely tolerated – it is a fundamental feature of the Japanese religious environment.

So how are we to reconcile the seemingly paradoxical situation of a society that is at once avowedly non-religious and yet simultaneously appears to support an abundance of religious institutions, celebrating thousands of matsuri every year? How do we make sense of people who self-identify as non-religious and yet are also recorded as Buddhist and Shinto adherents?

First off, the statistics are less contradictory than they appear. Official figures are based on estimates of affiliation supplied by the various shrines and temples, and therefore do not relate to personal beliefs or assess individual self-identity (and are likely to be inflated). Additionally, since the mainstream religious traditions in Japan do not require regular attendance at services, affiliation tends to relate to archaic mandatory registration systems or funeral services. Also, for many the idea of endorsing personal membership of a religion in Japan has negative connotations associated with uncomfortable proselytising and fanatical cults, as the infamous sarin-gas attack by the millennial cult Aum Shinrikyo on the Tokyo subway in 1995 continues to resonate in the public imagination.

So we shouldn’t pay too much attention to religious membership as an indicator of religion. For instance, although the World Values survey found only 11.8 per cent of Japanese respondents self-identified as a member of a religion, 40.8 per cent of the same respondents stated that they believe in God(s). Similarly, in the study I conducted last year, despite only 10 per cent self-identifying as religious, 43.5 per cent agreed that there was ‘a spiritual realm beyond the physical one’, 30.2 per cent agreed that ‘spiritual beings (such as angels and demons) exist’ and 36.5 per cent endorsed that ‘there is some kind of life after death’. These results indicate that religious affiliation in Japan is a separate issue from holding various supernatural beliefs and that personal beliefs are not taken into consideration by the official statistics on membership.

Yet it would still be a mistake to interpret these findings as demonstrating that Japan is a country where strong personal religious beliefs are central to religious practices. In contrast to the United States, where 48.8 per cent reported that God is very important to their life, only 6.1 per cent chose this option in Japan. Strong beliefs, I argue, are not an essential feature of religion in Japan. Rather, they are better understood as a feature of the particular monotheistic religions that happen to be dominant in the West. In many societies, supernatural beliefs are not regarded as requiring endorsement but are instead treated as self-evident truths or, as in the case of Japan, are given much less attention than practice. The endorsement of strong beliefs is not a necessary part of religion.

After the misogi in Kikonai, my research team and I met with the four young men at a celebratory dinner after the festival. We asked them what they thought of their experience. They framed their participation not in terms of beliefs or religious devotion, but instead talked about their respect for traditions, social connections, obligations and the possible blessings for the community. Similarly, when I asked them about the rituals’ potential role as a local rite-of-passage (the performers must be unmarried), none of them regarded it as particularly significant. One joked that his participation wasn’t likely to attract women in Tokyo, where he had moved for work.

The disparity between common Japanese religious practices and belief-centric views of religion was again brought into relief when a prominent psychology professor from the US, who was temporarily visiting my lab in Japan, encountered the domestic co-existence of Buddhist and Shinto altars. Most traditional family homes in Japan house both a Buddhist altar to honour deceased relatives (butsudan) and a Shinto altar, called a god-shelf (kami-dana), to bring blessings. This pluralistic practice goes largely unremarked upon by Japanese people, but it can be striking for those from more exclusive religious backgrounds. When the US professor learned of the practice, he turned to a Japanese colleague and asked if he had two altars in his home. Yes, at his family’s house, he answered. The professor asked in astonishment which of the two systems, if either, was the one that he really believed in. My Japanese colleague was puzzled. ‘Neither,’ he said, and then clarified: ‘…or maybe both!’ He had never really thought much about whether he believed in altars before, he explained.

Practice, in the Japanese religious environment, is given prominence over belief. This accords with the views about the Japanese expressed in Practically Religious (1998) by Reader and George Tanabe, another prominent researcher of Japanese religion. The authors’ core thesis is that Japanese religion is not primarily about endorsing specific beliefs or traditions in order to gain salvation in the next life but instead is orientated towards the attaining of practical benefits in this current life (genze riyaku) through the performance of various activities, such as visiting shrines and temples, purchasing amulets and charms, and saying prayers.

Practices that are claimed to offer healing, grant luck or other benefits are common in almost all religious systems, but Reader and Tanabe argue that in Japan these are not just some peripheral aspects of religion but instead ‘lie at the very heart of the Japanese religious world’; they represent the ‘common religion’ of Japan. Such worldly services are also endorsed both doctrinally and institutionally, with temples and shrines marketing themselves based on the various benefits they can provide. There are shrines and temples that cater for almost every conceivable desire, including improving success in romantic endeavours, passing exams, and more prosaic goals such as curing haemorrhoids or maintaining good dental hygiene.

This can occasionally generate tension, when popular worldly practices appear to contradict official doctrinal messages of renunciation, but such ambiguity is widely tolerated. Consider, for instance, the contemporary prevalence of marriage among Shinto and Buddhist priests in Japan. In contradiction to the popular Western image of Japanese religion as being populated by ascetic monks meditating in mountains, meditation halls are largely absent from most temples and shrines. Instead, priests are busy providing various religious services for fees. Indeed, the potentially lucrative nature of Buddhist funerals has contributed to a general aura of suspicion in Japan that many Buddhist priests are too focused on accumulating personal wealth.

Religion is not a category of human activity that is always and everywhere clearly distinguishable from other spheres of human life

The combination of worldly concerns with religion is not unique to Japan, of course. However, the discussion above highlights several clear discrepancies between religion in Japan and the typical associations derived from Western monotheistic traditions. So does the word religion describe what we find in Japan? Yes it does, but with one important qualification: for the concept of religion to remain a useful cross-cultural category it must be shorn of its Abrahamic assumptions and understood to refer to a range of concepts and traditions that not only cluster around supernatural beliefs, but also practices, like rituals and festivals.

Some disagree with this view, such as the religious studies scholar Jason Ananda Josephson at Williams College in Massachusetts who explained to me via email that ‘the word “religion” is a fundamentally Eurocentric term that always functions, no matter how well-disguised, to describe a perceived similarity to European Christianity’. Josephson elaborated on this perspective in his well-received book The Invention of Religion in Japan (2012), which details the various negotiations and political struggles involved in deciding what constituted religion in the country during the Meiji era. He highlights that the present-day translation for ‘religion’ in Japanese – shūkyō – is a ‘Meiji neologism’ that ‘transformed the things classified under it and the things excluded from membership’, and also explains that a big problem he has with the term ‘religion’ is that ‘it has a multiplicity of incompatible meanings’.

When I raised these points in a discussion with Ian Reader, he said that although he admires Josephson’s work, he strongly disagrees with his assessment that we should ‘jettison a term in the 21st century which has developed a set of meanings in that context because of its possible mid-19th century derivation’. He also explained that in Japan ‘there is an intellectual and political tradition that accords weight to the notion of “religion” as a category… [and this] indicated clearly that [it] is not some Western structure arbitrarily imposed… by colonial-style powers’. Reader also said that while the term can be vague, he still believes that the concept serves as a ‘viable framework of discussion and interpretation for scholars that enables them to engage… with scholars studying similar issues elsewhere’. This accords with my own experiences as a cognitive anthropologist working on large inter-disciplinary and cross-cultural projects that were only possible because we utilize a shared terminology that includes a nuanced definition of religion.

Religion is not a category of human activity that is always and everywhere clearly distinguishable from other spheres of human life. And it is also true that what would be referred to as ‘religion’ varies across eras and locations. Yet this does not make the term semantically incoherent, nor is it the case that modern usage of the term must cling to usages of the past.

The grand theories of old failed because they conceived of religion as a monolithic phenomenon that evolved linearly over time. Modern approaches do not need to endorse such assumptions. Instead, as with the definitions of religion which are currently favoured in the cognitive science of religion field, it is possible to recognise that religion does not refer to any single thing but rather to a family of related concepts that serve to identify a meaningful and circumscribed field of inquiry. We have no greater cause to abandon the term religion for its inherent fuzziness than we do to abandon other broad terms, like politics or kinship. Ultimately, we must step back from such academic minutiae and return to exploring what we find in the world by putting to use our always-imperfect analytical tools.