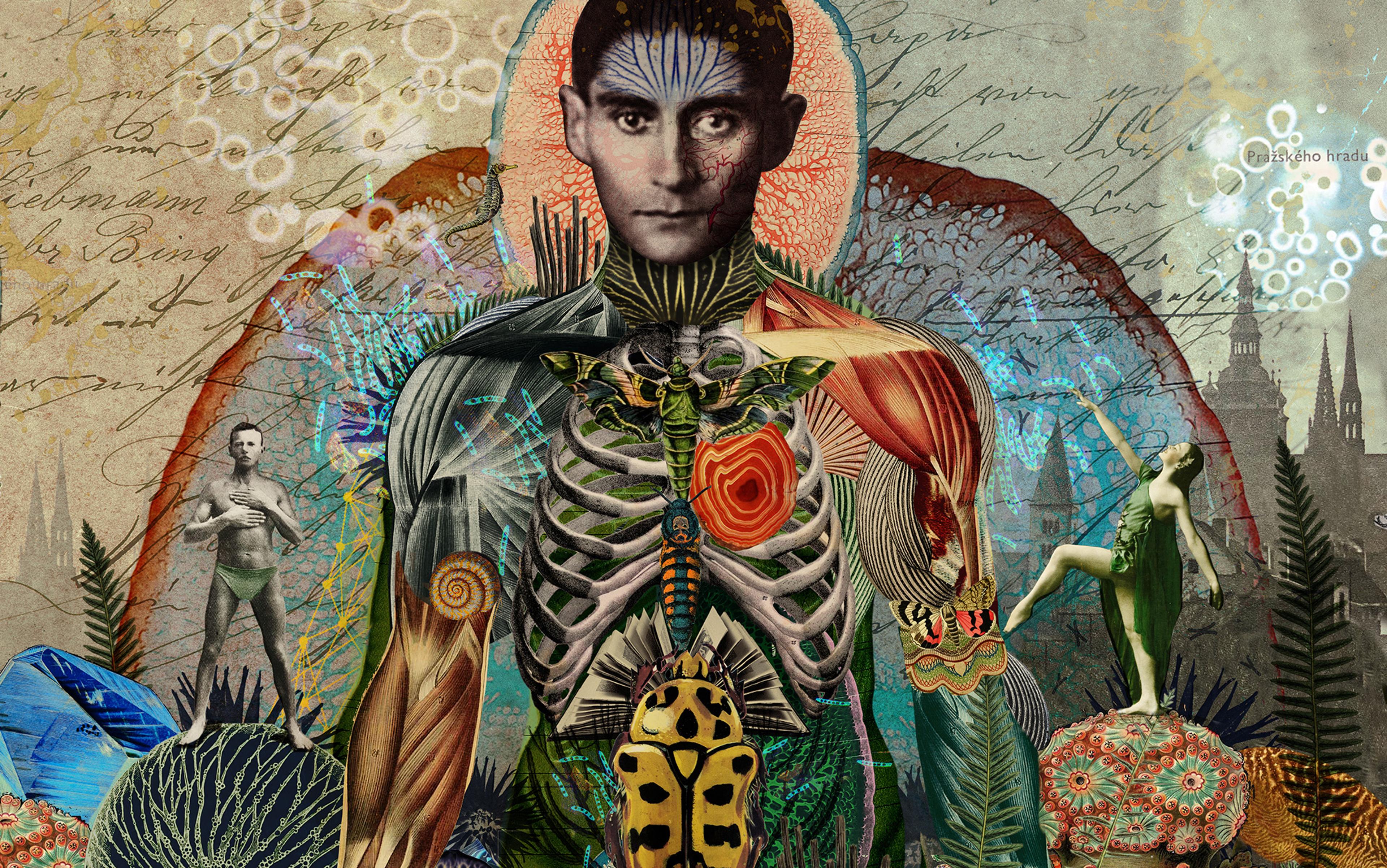

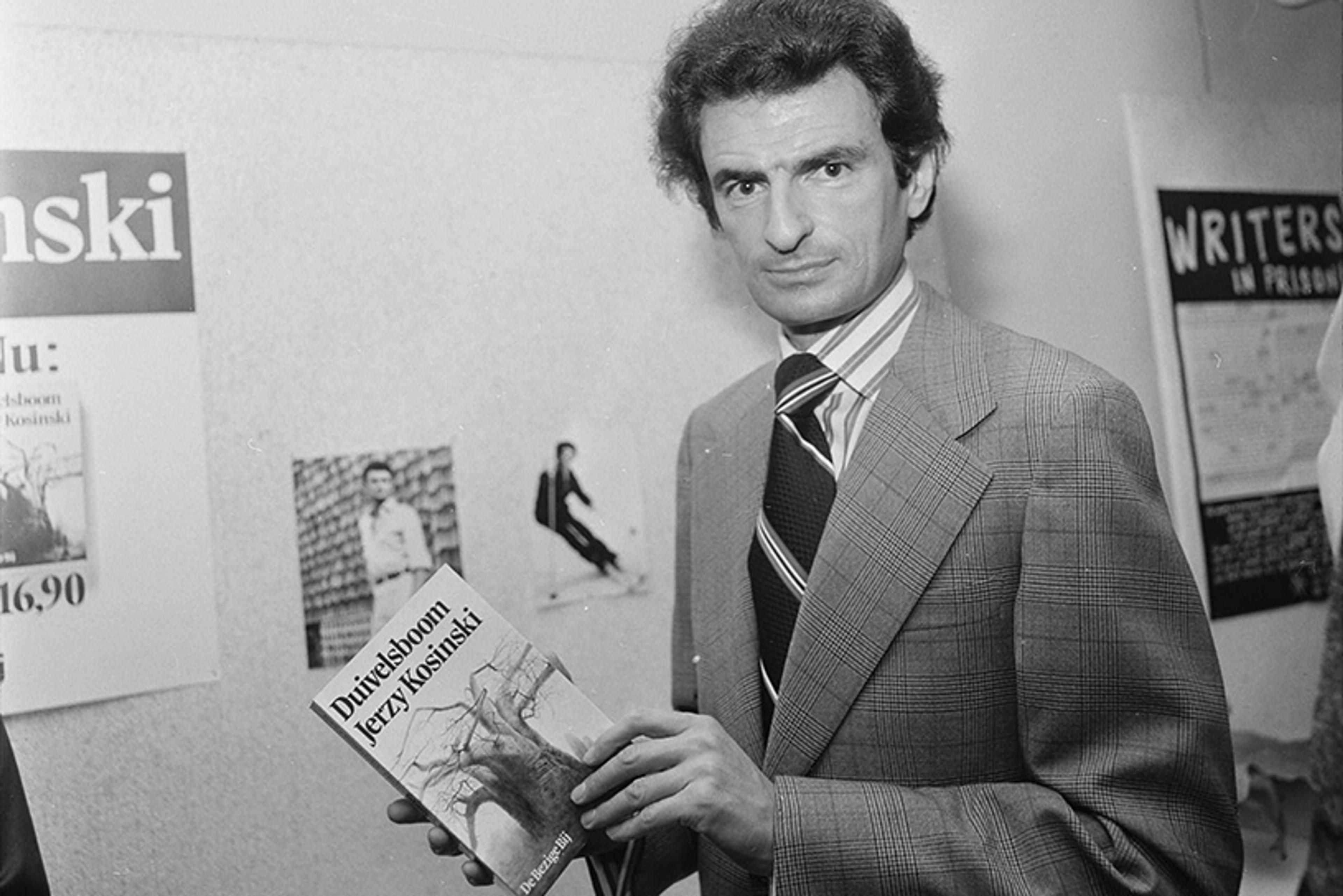

On a cold November evening in 1984, I was sitting on a stepstool in the ‘H’ section of the Coliseum bookstore near Central Park in Manhattan, cradling a volume of Ernest Hemingway’s short stories in my lap. Busy imagining myself on the hot plains of Africa in sight of snow-capped Kilimanjaro, my thoughts were interrupted when a pair of brown safari boots edged into view beside the page. I glanced up. The man leaning over me was the writer Jerzy Kosinski, author of The Painted Bird (1965), a terrifying novel about an abandoned, mute boy who drifts alone through a bleak, dangerous countryside, alternately sheltered or abused by the local peasants in what readers assumed was war-torn Poland during the Holocaust.

Polish American author Jerzy Kosinski in 1973. Photo courtesy National Archives

Kosinski was a man in trouble when we chanced upon each other. Two years earlier, with tens of millions of copies of his novels in print, Village Voice reporters charged him with literary fraud. Based more on innuendo than fact, their article derailed his literary career. Those details were not on my mind as he leaned over my shoulder, stretching out his arm to tap the spines of each of his novels as if he were counting. I tried to make it seem like I hadn’t noticed him, but all I was thinking was that certain books leave fingerprints on the mind, ready to be dusted with the memories of one’s life. The Painted Bird felt like a desperate note sent in a glass bottle that broke in my hands and made me bleed. It was almost three years after I’d read it, but I still could not shake the feeling that a private emotion lurked beneath the text, a leviathan of grief.

Back home, I wrote him a letter. I was a Wall Street analyst at the time, and accustomed to scrutinising business documents of publicly traded companies, examining them for the obvious story their CEOs and CFOs were intent on telling investors but also probing for the story they tried to hide. Oddly, this skill turned out to be useful when reading Kosinski’s novels.

Months later, in March 1985, he telephoned and invited me to dinner at an Italian restaurant near his apartment. For 90 minutes, we traded stories and laughter. Everything was fine until I asked a series of questions that startled him.

Naming his first novel, The Painted Bird, and his third, Being There (1971) – about a naive, reclusive gardener called Chance who finds himself suddenly thrust into the modern world where everyone mistakes his silence for wisdom – I set down my fork and said: ‘They both feel as if there’s a subtext, a hidden story beneath the surface.’ I wondered out loud if it was one of his writerly strategies to hide wartime details in female characters. The question made him so upset that he leapt from his seat as if to flee the restaurant. I grabbed his wrist and held on till he sat down again. Five or 10 minutes of absolute silence followed while, heads down, we both pecked at the remnants of broiled fish and potatoes on our plates.

To my surprise, when we were saying goodbye afterwards, he asked to meet again. I promised myself to tell no one what had happened that night. Memories of my maternal grandmother were surfacing – how she concealed her Jewish identity when she came to the United States, how she helped raise me as a Catholic on the outside with a hidden Jewish self. Not the same as living in Nazi-controlled Europe, but I understood something about hiding. Already the secret keeper for my grandmother, I felt compelled to keep Kosinski’s secret too. He may not have used words to answer my question about hiding childhood experiences in female characters, but his outsized reaction at the table felt like a confirmation.

Survival involved a combination of luck, planning, and the ability to live behind a wall of psychological silence

While Kosinski was alive, I didn’t fully grasp how our dinner encounter connected to the broader story of hidden Jewish children during the Holocaust. Kosinski was one of perhaps 5,000 Jewish children in Poland (out of almost a million) who made it through the war by hiding. The dinner had felt like a game of hide-and-seek with him, but his life taught him only the rules for hide-or-die.

At the time, the only other hidden child I knew about was Anne Frank. She and her family lived in a set of secret rooms in Amsterdam before being turned over to the Gestapo by unknown informants. Inside the Secret Annex, she wrote in her diary with the freedom of someone able to consider her Jewish identity and write truthfully about her family’s situation. Circumstances were markedly different for children in open hiding who attempted to live unnoticed among the non-Jewish population. Once the decision was made for them to go into open hiding, they had to forget the past overnight, masking themselves as faux Christians, and never – by a glance, an accent or a social mistake – reveal their original ethnic identity. Survival in this manner involved a combination of luck, planning, and the ability to live behind a wall of psychological silence.

By 1991, Kosinski had died and I’d left Wall Street for graduate school. I began researching the Holocaust’s hidden child survivors. That’s when I discovered AMCHA, the Israeli Center for Mental Health and Social Support of Holocaust Survivors and the Second Generation. Yvonne Tauber, who treated many formerly hidden children at the Center, coined the term ‘compound personality’ to describe how these people presented in therapy: a single individual with an external, age-appropriate self, concealing a suppressed, traumatised-child self from wartime.

The more I learned about the psychological dynamics that followed such children into their adult lives, the more I came to wonder how the suppressed child would express themselves in the grown-up texts they produced. Would their books involve dual perspectives, a split viewpoint that incorporated the child’s experience in hiding, with the adult reflecting on it? Memory for this group came in traumatic fragments, so would I find that too? Would the inner, suppressed self ever act up and perform a secret action? Yes, to all.

It was not hard to find adult writers expressing such a reality. The historian Saul Friëdlander, for example, wrote in his memoir When Memory Comes (1978) about his childhood-in-hiding at a Catholic boarding school in France:

I am the one who now preserves, in the very depths of myself, certain disparate, incompatible fragments of existence, cut off from all reality, with no continuity whatsoever, like those shards of steel that survivors of great battles … carry about inside their bodies.

This seemed true for Kosinski, too. In The Devil Tree (1973), his novel about a rich young man’s search for meaning within the corrupt world of the superrich, he wrote this description of his young alter-ego:

My real self is antisocial – a lunatic chained in a basement, grunting and pounding on the floor while the rest of my family, the respectable ones, sit upstairs ignoring the tumult. I don’t know what to do about my lunatic – destroy him, keep him locked in the cellar, or set him free.

His description seemed to be saying that no matter how successful survivors became in their new American lives, they carried a broken, internal self that suffered, even decades after the war.

Trying to sort out fragmented memories of his childhood, Perec developing a writing style that circled around voids

When starting my doctoral dissertation research, I first encountered the Parisian-born Georges Perec on a rainy afternoon in my university library. As I turned the pages of A Void (1969), a story about a group of friends searching for their missing companion named Anton Vowl, I realised he had written an entire novel without using the letter ‘e’. Running my finger down the paragraphs, I could almost feel their phantom presence. Without ‘e’, the author could not write père (father) and mère (mother) in his native French. This unusual writing technique even meant that the ‘e’ disappeared from his name, like members of his family vanishing one by one.

Georges Perec pictured at home in Paris, 23 November 1965. Photo by Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match/Getty Images

As I browsed other volumes on the shelves by or about Perec, his story gradually unfolded. Picturing a young boy in Paris, I imagined him clutching his mother’s hand before being loaded onto a Red Cross convoy to escape incoming German troops. His father was already gone, killed in the first year of fighting against the Nazis. His mother must have kissed him when she said goodbye, fervently hoping she would see him again. Instead, she was deported to Auschwitz, and he, like Friëdlander, was sent to hide in the French countryside. After the war, he was adopted by his paternal aunt and uncle. Perec spent the rest of his life trying to sort out fragmented memories of his childhood, developing a writing style that circled relentlessly around voids and disappearances.

Back home with an armful of his books, I opened his memoir, W, or the Memory of Childhood (1975). In this unusual book, I found myself travelling back and forth between two seemingly separate journeys – autobiographical chapters in Roman type alternated with italicised chapters of fiction. In the autobiographical thread, it seemed that Perec was acting out Henri Raczymow’s idea of mémoire trouée, a ‘memory shot through with holes’, that is to say, he might make a statement in one place and then deny it in another. For instance, he describes his father in military uniform with a ‘greatcoat [that] comes down very low’. Yet, a footnote at the end of that chapter asserts: ‘No, in fact, my father’s greatcoat does not come very low …’ Meanwhile, the fictional thread tells a tale about W, an island dedicated to extreme sports where losers pay for a loss with their lives. In this storyline, the adult Gaspard is sent in search of the young, deaf-mute Gaspard, who’d been shipwrecked with his mother and presumably swallowed up in W’s sporting culture. Reading these separate narrative threads felt like watching train tracks running parallel, never seeming to meet except at the horizon, an image not unlike the tracks approaching Auschwitz. Yet somewhere in the space between those tracks lay the paradox of Perec’s experience, hiding in plain sight.

The surprising point of convergence is a single page between Part 1 and Part 2 of Perec’s book. Following the established rhythm of a chapter in italic font (fiction) being followed by a chapter in Roman font (autobiography), I would have expected an autobiographical passage about his mother’s death at Auschwitz to follow on from the narrative about the shipwrecked boy. Instead, what appears is a page that’s blank, save for an ellipsis in brackets: ‘(…)’. Here, in five keystrokes, was the soundless wail of the repressed-child self in Perec that so many other hidden child survivors experienced. The ellipsis, the missing letters, the alternating chapters, the elaborate patterns. These weren’t just literary games but ways of approaching what couldn’t be confronted directly: something was there, something was gone. In that ellipsis, I recognised the faces of the parents he had lost, now only a parenthesis holding the family together, and sensed a traumatic grief so terrible that it swallowed language, even for a professional writer.

After Perec, I learned about Sarah Kofman, a French professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne. Throughout most of her life, Kofman held firm to the notion that her academic books were all that was needed to showcase her life’s story. She changed her mind in her late 50s and wrote Rue Ordener, Rue Labat (1994), a memoir whose title lists two addresses: one, the site of her family’s original home; the other, the street where she later lived in hiding. Together, these addresses represent the divided self she carried throughout her life.

Here, for the first time, Kofman described the cataclysmic events that overtook her family during the Second World War. Like Perec’s parents, Kofman’s mother and father had fled Polish pogroms and settled in Paris in the 1920s. Sarah was born there in 1934, the third of six children. Their childhood was shattered on 16 July 1942, when French gendarmes arrested their father, Rabbi Bereck Kofman. After the war, a survivor from Auschwitz told the family that Bereck had been buried alive at the camp for refusing to work on the Sabbath.

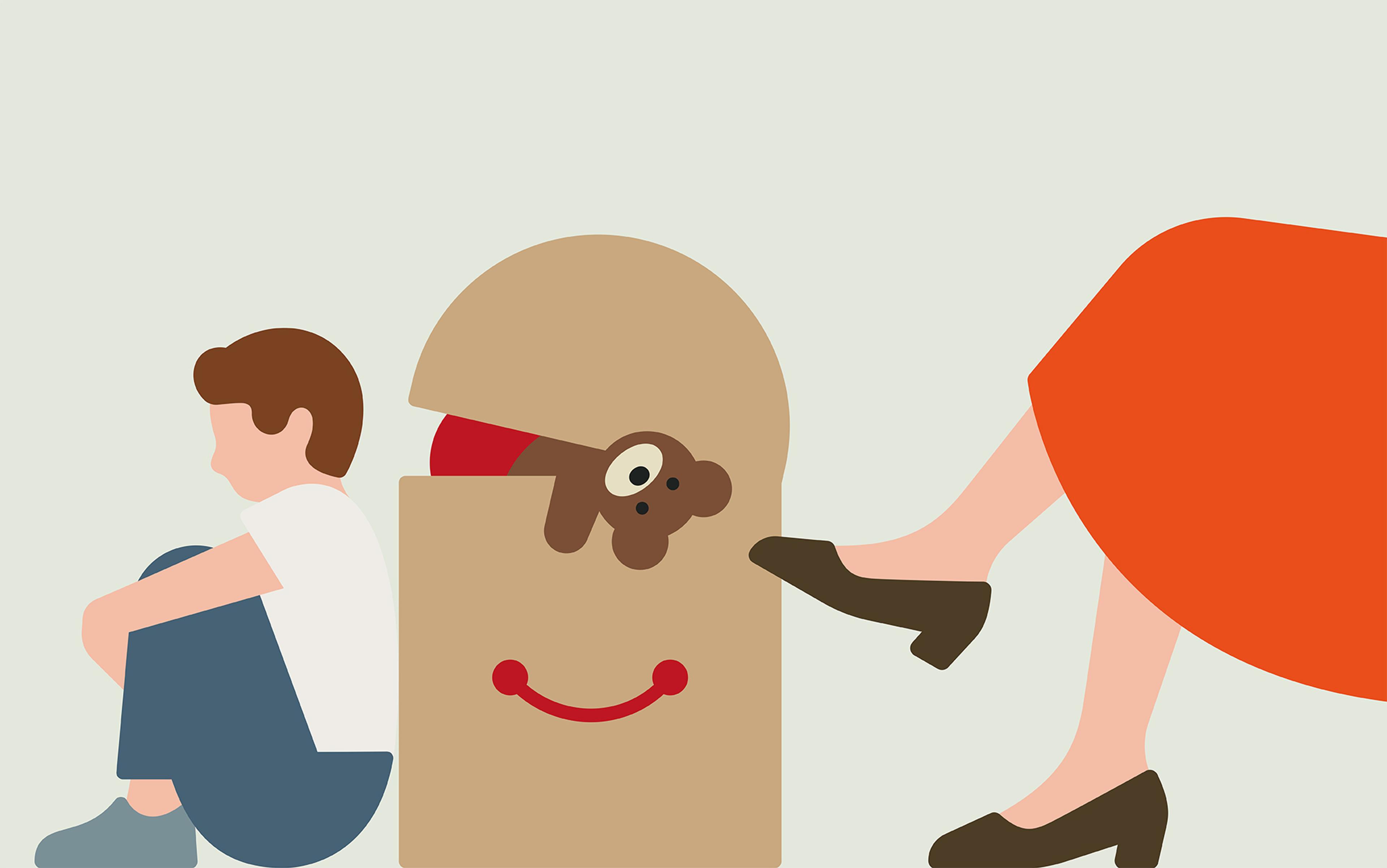

As the Gestapo’s actions became more frequent, Kofman’s mother found hiding places for all her children. However, the trauma of losing her father triggered severe anxiety in the eight-year-old Sarah. When separated from her mother, she would vomit and prove hard to handle. Fearful of harbouring a Jewish child, an action punishable by death, families who had agreed to hide her kept returning her to her mother. In February 1943, after a Gestapo raid that they just managed to escape, Sarah and her mother fled to the Rue Labat apartment of Claire Chemitre, a friendly Christian woman they knew from the neighbourhood, who might be willing to risk her life to shelter them.

All the Kofman children and their mother ended up surviving and were reunited after the Nazis’ defeat, but that period at Rue Labat came at profound psychological cost. To survive, Sarah had to inhabit two distinct identities. At Rue Ordener, she was a poor child in a traditional Jewish household where French was rarely spoken. At Rue Labat, Mémé, her new ‘grandmother’, renamed her ‘Suzanne’, fed her non-kosher food, taught her French, and educated her in typical French subjects, all things outside the realm of Sarah’s biological mother. Mémé recognised Sarah’s intellectual potential and cultivated it, much to the girl’s delight. Meanwhile, because there was nowhere else to hide, Mme Kofman was powerless to fight the hold Mémé maintained over her daughter. In fact, she’d been ordered early on not to leave her assigned bedroom, not even for meals, while Sarah/Suzanne ate with Mémé at the dining-room table. Sarah’s memoir reveals that Mémé even asked her to sleep in her bed. Much to her mother’s consternation, the young girl had happily obliged.

A reader may be left confused. What is fact? What is imagination? What is faulty memory?

This is how Sarah found herself torn between two women representing incompatible worlds. Wearing the mask of Suzanne kept her safe from arrest and death. Yet, accepting life as a kind of adopted daughter to a Christian Frenchwoman meant betraying her Jewish identity and abandoning her past. The childhood lesson that survival depended on concealing her true self shaped Sarah Kofman’s entire adult life.

After the war, this protective lesson evolved into a professional mask. Philosophy became Kofman’s refuge, allowing her to speak in the language of thought rather than to engage the emotions of her traumatic childhood. She published extensively without ever addressing her Jewish identity, Holocaust survival or personal history.

For decades, this philosophical mask successfully repressed feelings about her early life. A crack developed in 1987 when she attempted to reconcile her academic and personal worlds by publishing a book that posed ethical questions about how a writer could responsibly represent the Holocaust. In Paroles Suffoquées, later translated as Smothered Words (1998), Kofman also addressed her connection to the Holocaust and her father’s murder in Auschwitz.

This work unsettled her enough that she performed a secret action in 1987 when Mémé was ill and living in a hospice. Quietly, without publicising her action, Kofman let her hidden child speak and nominated Mémé for recognition as ‘Righteous Among the Nations’ at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust remembrance centre. Her application portrayed Mémé as a stranger who had heroically rushed to the Rue Ordener apartment to save her and her mother, rather than as a known community figure who sometimes came to light the Kofman’s stove on the Sabbath when Jewish law forbade such activity.

Yet, in her 1994 memoir, Kofman would later claim that an unnamed man from the neighbourhood was the person who’d come to warn her and her mother about the approaching officers. Knowing from local encounters that Mme Chemitre admired her blonde children, Mme Kofman took her daughter to Mémé’s apartment and convinced the woman to shelter them both.

In the story divulged only to Yad Vashem, Mémé was the star who brought Sarah and her mother to the safety of her apartment. But, in the later memoir, it was her biological mother who acted quickly and courageously, taking a calculated risk that she and her daughter would find safety with a local, non-Jewish neighbour. A reader may be left confused. What is fact? What is imagination? What is faulty memory? Perhaps the discrepancy illustrates Yvonne Tauber’s concept of compound personality in action.

Like Sarah Kofman, Jerzy Kosinski left childhood with a tremendous need to maintain a psychological hiding place similar to the one that had helped him survive the war. Successfully hiding became a lifelong compulsion: he would hide from guests in his apartment; he told me at our dinner that he could hide anywhere in the restaurant without being found. This need to hide helped him choose his life’s motto. His biographer James Park Sloan pointed out that Kosinski adopted René Descartes’s phrase ‘larvatus prodeo’ (meaning ‘I go forward masked’) – as his guiding ideal. The expression left a mark in his writing. For example, his protagonist in Cockpit (1975), a novel about a man who deliberately erases his past as a way of gaining freedom in new encounters, explains that the purpose of a mask was not to lie. ‘It is the witness who deceives himself,’ he says, ‘allowing his eyes to give my character credibility and authenticity. I do not fool him; he either accepts or rejects my altered truth.’ This approach was the exact one a hidden Jew needed during the Holocaust. To stay alive meant one had to disappear inside the blind spots of other people’s expectations.

That is what went wrong during our dinner. By wondering out loud if he was hiding traumatic material in female characters, I’d expressed an idea about something under the mask.

In hindsight, I realise that, three years after our dinner, Kosinski gave me an opportunity to hear an explanation of what had disturbed him then. It was late June 1988. Kosinski had just published his final novel, The Hermit of 69th Street, a story about a writer who ends up flung into a river by two assailants. A 527-page behemoth of a book, festooned on nearly every page with different typesetting fonts, as well as quotes from more than 500 other authors, Hermit came into the literary world with fanfare. At the same moment, however, Kosinski hid from his wider reading public a short story he’d written for a very small-circulation literary journal called Confrontation, published at a university near my home.

‘Chantal’ felt like a hand grenade lobbed at me. I changed my number so Kosinski couldn’t call me anymore

On a quiet Saturday afternoon that June, I rode down the elevator at my Greenwich Village co-op to get the mail. As soon as I saw an envelope with his return address, my hands started to tremble. The envelope had arrived the week after I’d last seen him, on the night of his 55th birthday, at one of his public lectures. Because we’d argued in public then, his angry words were still ringing in my ears.

Back upstairs, I locked the apartment door and sat down on my bed. Inside the envelope was ‘Chantal’, the only short story he ever published, the only fiction he named for a woman.

The story follows a female fan who has written to an author, Samuel Kramer, who is visiting her country. Kramer contacts her and invites her to his hotel. They agree to talk while strolling through a nearby forest. In one clearing, they sit together as she explains how artists in her country create female characters only to destroy them in the end. In a second clearing, the author and his fan encounter a group of mercenaries. Chantal verbally provokes them. There, the plot splits – in one thread, Chantal and Kramer are killed by a hidden landmine; in another thread, Chantal is attacked by the soldiers. Yet, either way, at the end of the piece, Chantal emerges physically unscathed.

Both endings were frightening, so ‘Chantal’ felt like a hand grenade lobbed at me. On Monday morning, I changed my phone number so Kosinski couldn’t call me anymore.

Two decades later, while beginning my doctoral dissertation about hidden children, I sought advice from a trusted individual with experience treating Holocaust survivors. I wrote to the psychoanalyst Henry Krystal, a former inmate at Auschwitz and other camps who had done groundbreaking work on PTSD among Holocaust survivors. He had met Kosinski in person and recorded his own video lecture on the author – ‘Jerzy Kosinski: The Ravages of Childhood Trauma’.

When we talked on the phone, Krystal focused on a paragraph in ‘Chantal’ that comes just before the violence with the mercenaries erupts. Kramer is focused on a nearby dragonfly, his way of ‘distancing himself from imminent reality’, Kosinski wrote, ‘by disconnecting his imminent narrative focus’. Krystal suggested this sounded like an act of dissociation, a moment where terror is so great that someone’s consciousness seems to jump across the room, allowing the person to watch what is happening to themselves as if it is happening to someone else.

This interpretation made sense. Slipping some of his traumatic memories into the character of Chantal when the soldiers attacked her would have helped him describe violence that happened to him in childhood while keeping an emotional distance.

What better place to hide autobiographical information than in a fictional female?

The notion of a gender disguise is strengthened by the penultimate line of Hermit, Kosinski’s novel that was published in the same season as ‘Chantal’. In Hermit, Kosinski asks readers to imagine the book’s male protagonist as ‘the unsinkable Lotus Man disguised as the American Unsinkable Molly Brown.’

In September 1988, a few months after the story had been published, the gossip columnist Cindy Adams from the New York Post asked Kosinski if his personal life was the template for the male lead in a play he was trying to get produced. His reply? ‘No, I am the woman.’ He had trained readers from the outset to connect his male protagonists with himself, so what better place to hide autobiographical information than in a fictional female?

I stopped writing to Kosinski in 1988 but, just before his suicide in May 1991, he wrote to me twice. I always wondered why, until I discovered that, during those weeks, he’d arranged to publish ‘Chantal’ in a Canadian magazine without telling the editors it had already been published in America. Perhaps he’d thought of me because of the confrontation we’d had on his 55th birthday, and that made him mail ‘Chantal’ to me. Perhaps he still wanted to know what I thought of the story.

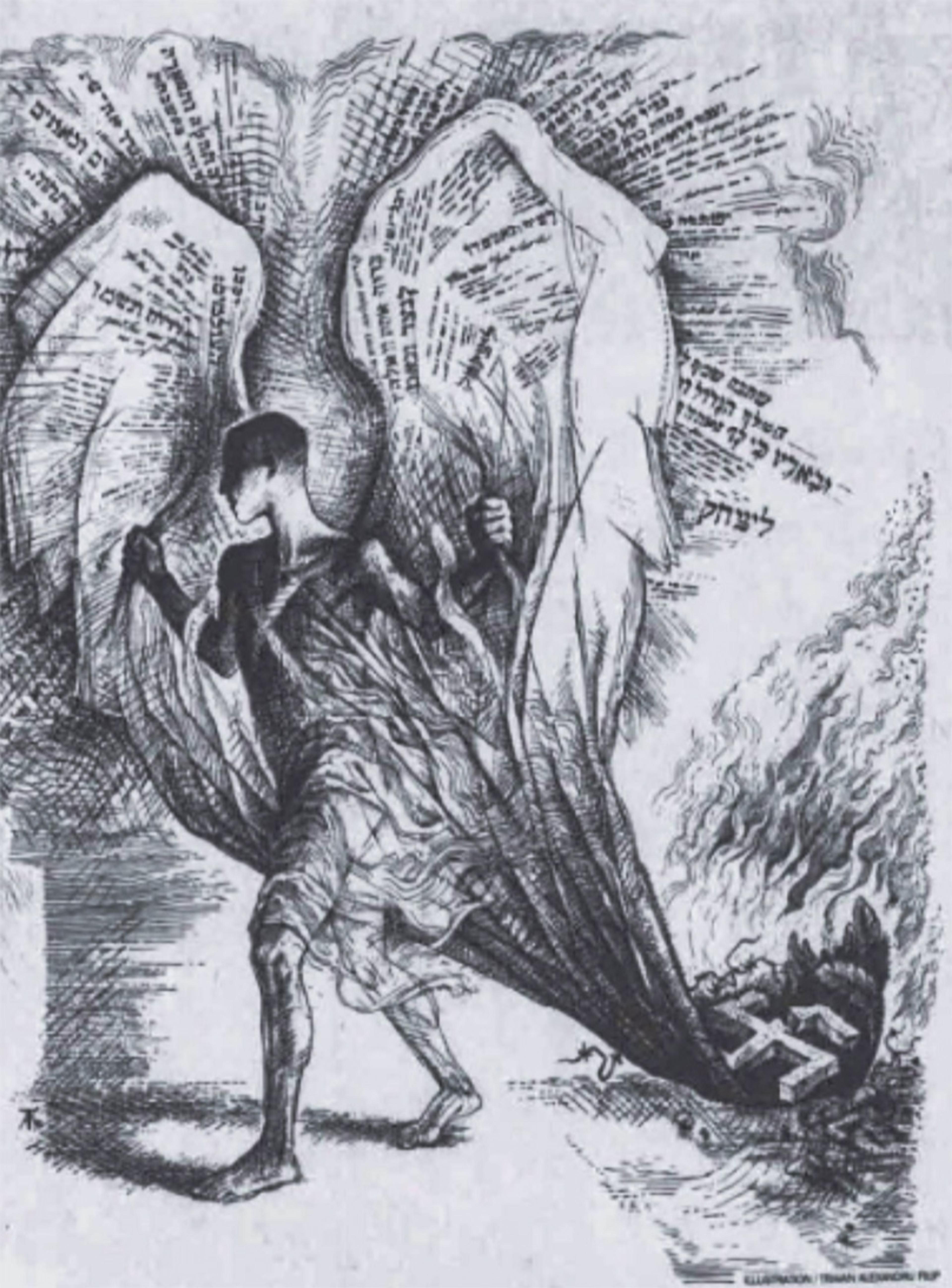

The last envelope came days before his death. This time, no handwritten message, just a photocopy of an essay he had published in The Boston Globe suggesting that Americans should concentrate less on the Holocaust and more on Jewish cultural achievements. It took a long time to realise that what he probably wanted to communicate was not the essay itself, but the accompanying pen-and-ink illustration. The Romanian artist Traian Alexandru Filip had drawn a striding angel/man, walking off the page. His trailing wings are on fire, weighed down by a swastika as though the conflagration had caught him and he couldn’t escape. That, it seemed, was what Kosinski wanted to tell me. Like Kofman, he couldn’t break free.

Illustration by Traian Alexandru Filip that accompanied Kosinski’s article ‘The Second Holocaust’ in The Boston Globe. November 4, 1990. With gratitude to the Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe

I regret not understanding enough at the time to apologise to him for my questions at dinner.

What these three writers taught me is that traumatic grief can overwhelm an individual even years later. No one can deny the suffering that occurred in places like Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, but the writings of children whose identities were suffocated so that their bodies might survive also show a kind of suffering that even success cannot heal.

What I learned from the man who leaned over me in the Coliseum bookstore changed my life.