Imagine you’re the manager of a café. It stays open late and the neighbourhood has gone quiet by the time you lock the doors. You put the evening’s earnings into a bank bag, tuck that into your backpack, and head home. It’s a short walk through a poorly lit park. And there, next to the pond, you realise you’ve been hearing footsteps behind you. Before you can turn around, a man sprints up and stabs you in the stomach. When you fall to the ground, he kicks you, grabs your backpack, and runs off. Fortunately a bystander calls an ambulance which takes you, bleeding and shaken, to the nearest hospital.

The emergency room physician stitches you up and tells you that, aside from the pain and a bit of blood loss, you’re in good shape. Then she sits down and looks you in the eye. She tells you that people who live through a traumatic event like yours often develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The condition can be debilitating, resulting in flashbacks that prompt you to relive the trauma over and over. It can cause irritation, anxiety, angry outbursts and a magnified fear response. But she has a pill you can take right now that will decrease your recall of the night’s events – and thus the fear and other emotions associated with it – and guard against the potential effects of PTSD without completely erasing the memory itself.

Would you like to try it?

When Elizabeth Loftus, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, asked nearly 1,000 people a similar question, more than 80 per cent said: ‘No.’ They would rather retain all memory and emotion of that day, even if it came with a price. More striking was the fact that 46 per cent of them didn’t believe people should be allowed to have such a choice in the first place.

Every day, science is ushering us closer to the kind of memory erasure that, until recently, was more the province of Philip K Dick. Studies now show that some medications, including a blood-pressure drug called propranolol, might have the ability to do just what the ER doctor described – not just for new traumas, but past ones too.

Granted, that future is not yet here. Most of the time, we’re still better at subconsciously editing our own recollections than any new technology is. But with researchers working on techniques that can chisel, reconstruct and purge life’s memories, it becomes crucial to ask: do we need our real memories? What makes us believe that memory is so sacrosanct? And do memories really make us who we are?

Many would argue that humans are driven by their stories. We create our own narratives based on the memories we retain and those we choose to discard. We use memories to build an understanding of self. We lean on them to make decisions and direct our lives.

But what happens to our sense of self if we purge the most distasteful memories and cherry-pick the good ones? When some things are hard to think about, or so injurious to our self-image, are we better off creating a history in which they no longer exist? And if we do, are we doomed to repeat our mistakes without learning from them, doomed to fight the same wars? By finding ways to erase our memories, are we erasing ourselves?

Our memories aren’t fixed. We already edit them: sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. Sometimes by ourselves, and sometimes when other people’s recollections filter into our own. We forget. We ‘remember’ incorrectly. We can even train our brains to remember facts and moments with greater acumen.

Think about your first kiss. No, go back further, to the first time you rode a bike. How clear is that memory? Is it picture-perfect or has it acquired a sepia tint and become a bit tattered around the edges?

The first time I balanced on a two-wheeler was in front of our little ranch-style house on a quiet street in northern California. I was perched proudly, if hesitantly, on the flowered banana seat of a shiny purple Schwinn that my father had just separated from its training wheels. ‘Don’t let go,’ I told my mom before we pushed off. She nodded and I started peddling as she grasped the rounded chrome handle on the back of the seat. ‘Don’t let go!’ I yelled again, and glanced back to find that she had, in fact, let go and was now half a block away, laughing and looking oh-so proud. I promptly fell. And then, because I’d scraped my knees, I started to cry. She came running up and I screamed at her, feeling betrayed.

At least, I think that’s what happened. Thirty-five years later I’m not so sure. Perhaps adult-me has re-interpreted what five-year-old me was feeling. Or perhaps, over the years, every time I pulled this memory up to the surface and told the story, I changed it ever so slightly, until what I remember now is more fiction than fact.

For decades, most memory researchers compared memories to photographs, and our brains to albums or filing cabinets stuffed full of them. They believed that each photo required an initial development period – much the way that pictures are processed in a darkroom – and then was filed away for future reference.

But in the past few decades, scientists have discovered that memory is far more plastic than that. It doesn’t just fade like a photograph tucked away in an album. The details subtly morph and shift. It’s malleable. And some research suggests it might be erasable.

Memories overlap and intertwine and connect and diverge like the tangled branches of an old lilac tree

Individual neurons communicate using chemicals called neurotransmitters, which flow from one neuron to the next across synapses – small gaps between the nerve cells. When memories are formed, protein changes at the nerve synapses must be consolidated and translated into long-term circuits in the brain. If consolidation is interrupted, the memory dissolves.

Different types of memories are stored in different places in the brain, and each memory has a dedicated network of neurons. Short-term memories such as a grocery list or an address live, briefly, in the pre-frontal cortex – the foremost area of the folded grey matter that encases the brain. Fear and other intensely emotional memories exist in the amygdala, while facts and autobiographical events are located in the hippocampus. But memories aren’t isolated in these different areas – they overlap and intertwine and connect and diverge like the tangled branches of an old lilac tree. Even when a factual memory fades it can leave an emotional trace behind, much the way that the lilac flower still knows how to open once it’s been snipped from the tree. Much the way the flower’s scent instantly transports you to a particular place and time, even if you can’t remember what you were doing or why you were there.

In 2000, two neuroscientists at New York University, Karim Nader and Joseph LeDoux were studying memory in rats when they discovered that the very act of recalling a memory puts it at risk of being altered or possibly erased. When a rat is afraid, it freezes in its tracks. Nader trained his rats to associate a particular tone with a mild electrical shock – every time he played it for them, they froze. As much as a year later, they still froze whenever they heard it, proof that the memory had consolidated and remained intact. Then, he injected a drug that blocked protein formation into each rat’s amygdala, the brain’s emotional strongbox, and played them the same sound but this time without the shock. The next day, the animals had no reaction at all to the tone.

The results were the first to prove how it might be possible to alter a memory that had already been stored, says Nader, who’s now at McGill University in Montreal. ‘We showed that just by recalling a year-old memory, a circuit can go back to being unstored and has to be stored again.’ With each recall, the memory was being reconsolidated – a process akin to pulling a picture out of that album, telling a story about it, then trying to reposition it exactly as it was. But the drug disrupted that process, as though someone had closed the album and spirited it away before the photo could be replaced. Now, with nothing to reinforce the rats’ memories upon recall, the memories appeared to evaporate as though they had never existed.

Upon hearing about Nader’s research, one of his colleagues at McGill, the psychologist Alain Brunet, began looking into whether the finding could be applied to people with PTSD. This condition is less a problem of remembering and more of not-forgetting, when the mind repeatedly plays back a disturbing chain of events, each time prompting the same feelings of fear and distress that were present the moment it happened.

The drug that Nader injected into his rats isn’t approved for most uses in humans. But another one that blocks protein formation in the amygdala is inexpensive, safe, and readily available: the blood pressure-lowering drug, propranolol.

Brunet has now performed a number of trials in people with PTSD – with as few as one session and as many as six – and seen some intriguing results. By administering the pill, waiting an hour, then asking his subjects to write down the traumatic story in as much detail as they could remember, Brunet found that some who had suffered PTSD for years began to look back at the event and remember most of the details while feeling… well, not much at all.

Scientists think it might work like this: norepinephrine is a stress hormone, a neurotransmitter that enhances emotional learning in the brain. Propranolol blocks its effects, preventing its involvement in reconsolidation of the retrieved memory. ‘The reconsolidation blockade has potential to become a universal treatment for PTSD. And PTSD is a universal problem,’ Brunet told me.

Other researchers have tried to repeat Brunet’s work, with greater or lesser success. In two separate studies, led by Brunet and the Harvard psychiatrist Roger Pitman, ER patients who took propranolol within six hours after a trauma appeared protected from experiencing intensely physical reactions when they recalled the event a few months later. It was these studies that Loftus referenced when she created her thought experiment – and that her subjects believed should not be allowed to go any further.

Because propranolol can seemingly erase emotional fear without affecting factual memory, it also holds promise for other anxiety-related disorders. Last year, Merel Kindt, a psychology researcher at the University of Amsterdam, used the drug to help people with arachnophobia to overcome their fear of spiders. Although they clearly remembered being afraid, Kindt’s subjects could now touch and even hold a tarantula.

New studies continue to reveal ways in which memory reconsolidation might be helpful, and multiple mechanisms that could be exploited for memory editing. By disassociating addicts’ memories of being high from their fond feelings toward the experience, scientists have looked at the potential of propranolol to cure alcohol addiction in people, and have even tested it for treating heroin and cocaine addiction in rats. Others are interested in a different drug, called Blebb, to slice out methamphetamine-related memories.

If this same memory-dampening pill could be used to help addicts, would Loftus’s subjects feel differently about its value? Could a judge ethically order this kind of therapy for chronically troubled addicts? When is memory expendable for the good of an individual or of society? And why is it less tolerable to use medication to erase or suppress a memory than it is to rely on our own brains to do the work?

‘Dealing with trauma is like strengthening a muscle. If you’ve done your bicep curls, the next time you have to lift a heavy box you can do it more easily’

The human brain is remarkably flexible. Its ability to selectively prune our memories’ errant branches is a necessary adaptation. If we remembered every moment of every day, most of us would get too bogged down in our own minds to be functional. Psychologists believe that the human brain has evolved to forget the trivial stuff and highlight important episodes, especially negative ones, so that we might better predict future events and know how to handle them.

That can make trauma harder to expunge, perhaps for good reason. ‘Traumatic experiences give you an opportunity to think about who you are in the moment that life really disrupts you. They make you ask: “What kind of person am I? How did I get out of it?”’ says Kate McLean, a psychologist who specialises in narrative identity at Western Washington University in Bellingham.

‘Dealing with trauma is like strengthening a muscle. If you’ve done your bicep curls, the next time you have to lift a heavy box you can do it more easily,’ she says. ‘People who don’t deal with or who forget [trauma] are not necessarily less happy, but will they be able to deal with the challenges that come next?’ She postulates that they might. But, she says, they could also discover that this kind of temporary coping strategy has consequences up the road.

I have no need to remember what I had for lunch last Wednesday, nor what I wore to that REM concert in 1995 (and I probably don’t want to). I do, however, clearly remember how I lost my footing at the top of the 57th Street subway entrance and bumped down a flight of stairs to land in a wet, embarrassed heap. I will never again forget that metal stair treads get slippery in the rain.

As mortified as I felt, however, the experience doesn’t seem like something I’d want to erase from my memory. Even the most red-faced, shameful moments of my life aren’t something I want to forget: they make me who I am. They are my cautionary tales, my forehead wrinkles. They help me navigate relationships more tactfully and better predict potential outcomes.

If someone were to ask me how I felt about scrubbing away emotional memories, I’d advise them to think hard about it. After all, that’s what I did, and I might never forgive myself.

I am one of the people McLean’s warning is meant for, one of those people who at some point made a conscious decision not to deal with one of life’s challenges. I have a gaping hole in my memory where my father should be, the result of a particularly effective attempt at not dealing by my adolescent brain.

My father had multiple sclerosis. It wasn’t something I thought much about growing up, other than dedicating a sixth-grade science-fair project to describing the disease. It’s an autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system, in which damage to the protective nerve sheaths disrupts neural signalling. It can cause everything from vision problems to paralysis. For my dad, at first, it mostly meant bouts of dizziness and occasional weakness.

One January afternoon when I was 12, however, I walked in after school to see both of my working parents at home in the middle of the day. Something was clearly wrong. My father had caused a car accident that morning and, while both he and the person he’d hit were uninjured, he had no memory of how he got there – a neighbourhood in the opposite direction from his office – and remained confused about the gender of the other driver. It was our first clue that his disease was about to take a rare, devastating turn, and steal not only his mobility but his mind.

In a way, it stole my mind, too.

Within six months, my father – a toxicologist and epidemiologist with a PhD in biochemistry – was spending his workdays staring vacantly out of his office window. He went from a sharp and quick-witted (if occasionally acerbic) debate partner to someone who was dull and vacuous (if mostly pleasant). He displayed all the joy and petulance of a four-year-old and had trouble holding up his end of anything but the simplest conversations.

Despite 12 years of family trips, despite nightly reading The Hobbit together before bed, I do not remember what my dad was like before he lost his mind

His body soon followed. The medications he took to help him walk caused terrible convulsions that left him shaking on the floor. A lifelong smoker, he’d light a cigarette and then forget he was holding it, sometimes singeing the tips of his fingers or, once, dropping it in the bathroom where it melted a hole in the linoleum. Within months, he progressed from cane to walker to wheelchair, and eventually had so much trouble swallowing he required a gastric feeding tube for nutrition and a Styrofoam cup to spit into so he wouldn’t choke on his own saliva.

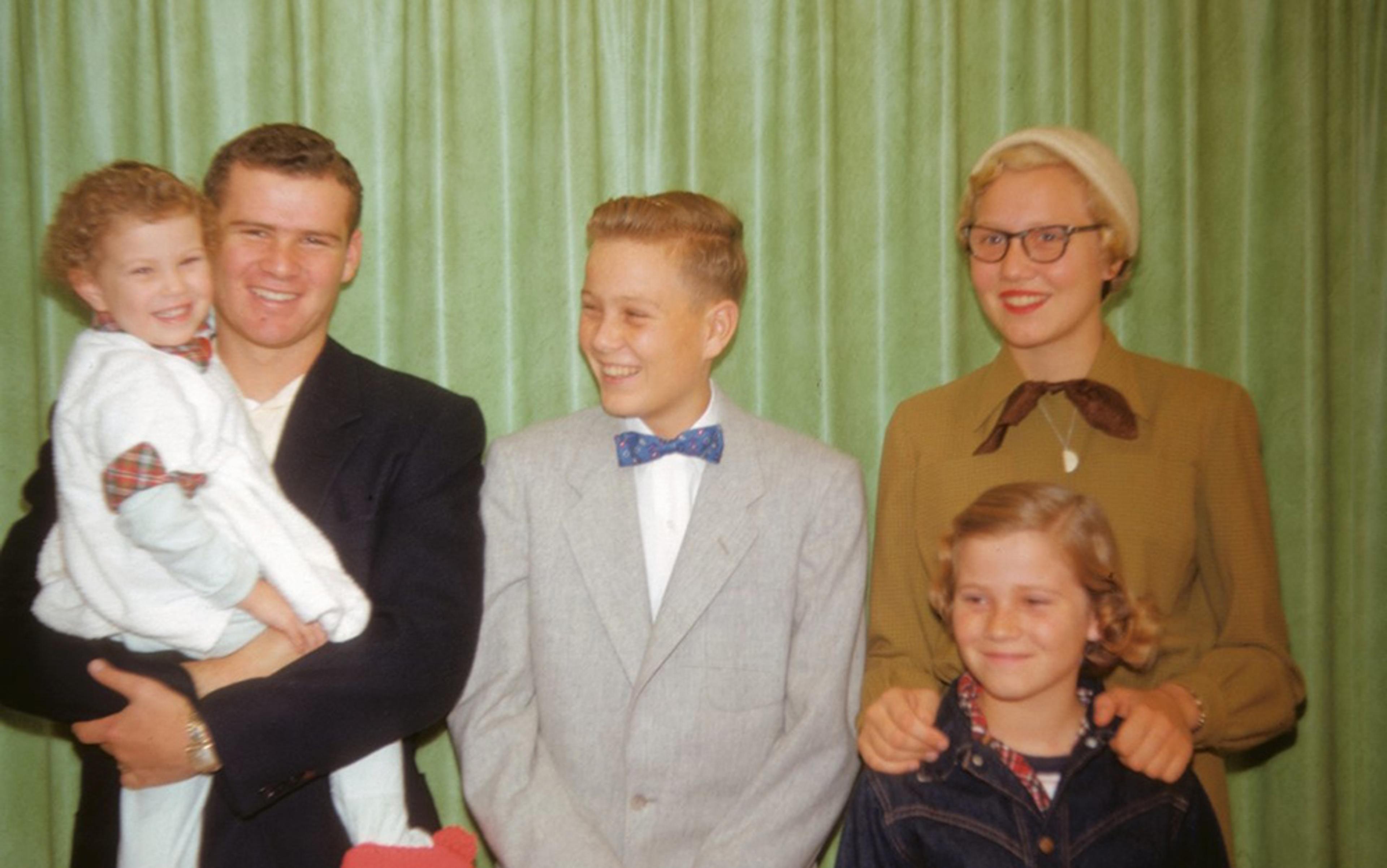

I remember all of this quite clearly. I remember that damned Styrofoam cup, the shiny blue of his wheelchair, the glassy look in his eyes. I remember how he hardly recognised me but how he lit up with the purest smile when my mother entered the room. And despite the fact that I was almost a teenager when the disease began to ravage my father, despite 12 years of prior history dense with family trips and holidays, despite a nightly tradition reading The Hobbit and other books aloud together before bed, I do not remember what my dad was like before he lost his mind.

It’s not that I don’t remember doing all those things – I do. I just can’t remember him. On the day of that first bike ride, even though he had just taken the training wheels off my purple Schwinn, I have no idea if he was standing next to my mother when I fell or if he was even there at all. It’s as if I have taken a scissor to my memories and sliced him right out of the photographs.

At the time, I did it quite intentionally. Every time my mother started to ask: ‘Do you remember when your father…’ I would cut her off abruptly. ‘I don’t want to talk about it,’ I’d say. Then I’d force my brain to bounce past it like a stone skipping off a pond and focus instead on something less painful, usually the man he had become. Rather than dwelling on the father I’d lost, my teenage brain lessened the heartbreak by replacing him with the man who sat in that blue wheelchair. Decades later, I can’t remember him as anything else, no matter how hard I’ve tried.

According to Michael Anderson, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge, I did something called ‘retrieval suppression’, in which someone intentionally takes mental action to prevent remembering something unpleasant – a process facilitated by the prefrontal cortex. So far, the emotional stronghold of the amygdala is what researchers understand best when it comes to memory suppression. Yet it’s my hippocampus, the area where factual memory lies, that seems to have the (figurative) holes. Intentional suppression works because we engage the brain’s prefrontal cortex to help us temporarily interrupt hippocampal function, briefly preventing it from encoding or consolidating memories.

Psychologists have long suggested that this kind of memory suppression takes a toll. According to Freud, memories pushed deep into the subconscious mind continue to influence a person’s thoughts and actions long into the future.

But Anderson has found that suppressing a memory also suppresses its subconscious effect on behaviour. He uses a procedure dubbed ‘think/no-think’ to better understand suppression in his study volunteers: first he shows them a picture or a word, then he directs them to either think about it or to intentionally shut down the retrieval process. To look specifically at its effect on behaviour, he and his colleagues asked volunteers to learn a set of word-picture pairs so that a word would prompt them to think of the coupled object (be it a motorcycle or a potted plant). But if the word itself was in red, they told participants to intentionally suppress any thought of the associated object when it popped to mind. When the researchers later showed them pictures of the objects, their subjects had a slightly harder time identifying them.

Some clinicians take the stance that memory suppression can be unhealthy, but this may be based on false assumptions, Anderson says. ‘Maybe it’s not a bad idea to suppress them after all. By giving unwanted memories undue attention, you could ensure they continue to stick around.’

Earlier this year, using the same think/no-think technique, he found that intentional suppression creates what he calls an ‘amnesic shadow’, one that spreads beyond the unwanted memory like a tree pruned a bit too enthusiastically. Participants in Anderson’s trial found that not only were they unable to remember objects they were trying to suppress, they were also less likely to remember objects they learned shortly before or after one they tamped down. It’s a finding that helps explain why people who experience harrowing car crashes and other distressing events often can’t remember what immediately preceded the trauma. It could also help explain why I have so few memories of doing anything at all with my father.

My sliced-up memories define my understanding of myself and have become part of a narrative I no longer want to change

Those memories might not be gone forever. A recent study in the neurologically simple sea slug indicates that interrupting reconsolidation might not be erasing memories but instead simply blocking our access to them. David Glanzman, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, has found that when neurons of the sea hare known as Aplysia californica are transferred to a petri dish, they can be trained much like Nader’s shocked rats. And as with those rats, when Glanzman and his colleagues triggered a memory of the shock and then dosed them with a drug that blocks protein formation, a number of synapses disappeared. But the synapses that dissolved appeared to be random – they weren’t necessarily those associated with the shock. When the researchers went back to the intact animals to see if they could reinstate the shock memory, they found that just a few shocks were enough to restore memories that should have been completely erased. This told them that the memory was located outside the synapses; they traced it to the cell’s nucleus, a part of the neuron that remains intact even as synapses come and go. Deep within the brain, or at least in the brain cells of a sea hare, memories persist.

Yet knowing this, knowing someone could one day tell me that they had found a way to grant me access to my memories of my father, I’m no longer certain I would try.

I spent years trying to find those memories. I asked relatives and friends for stories. I stared at faded family pictures trying to infuse them with the personality and warmth that comes only from the act of reminiscing. But perhaps all this time I’ve been looking for the wrong thing. Perhaps it’s okay to let the memories go. Over time, my sliced-up memories have defined my personal understanding of self and have, ever so gradually, become part of a narrative I’m no longer sure I want to change.

Yes, my over-pruned tree is missing some branches and appears rather lopsided. Its flowers don’t always open the way they should. But it’s also sprouting new leaves in places I never expected, and its crooked visage is simply part of who I am. Rather than trying to fill those empty holes, I can now look at the negative space and see it – all of it – as a part of me.