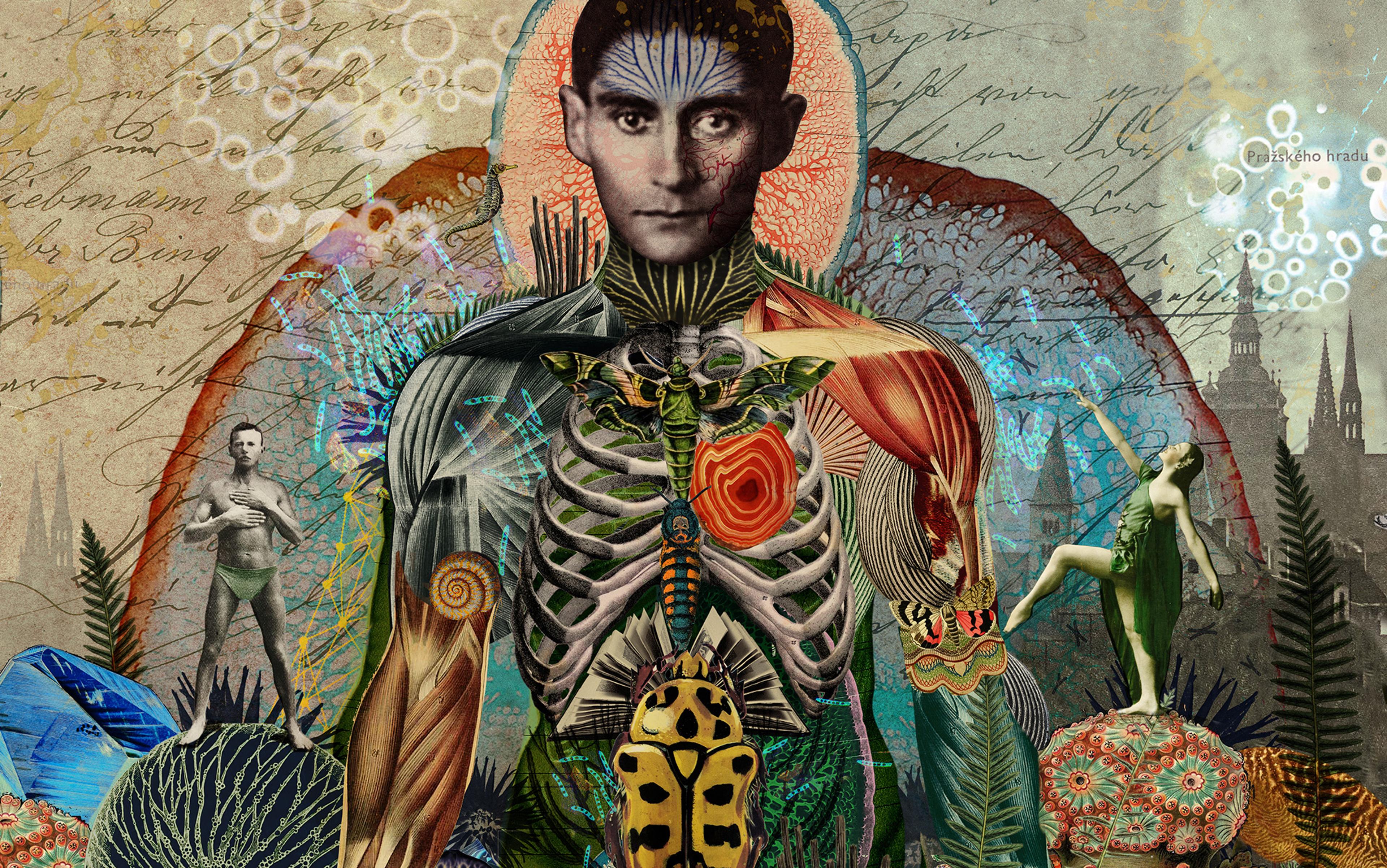

A few months before he died, Franz Kafka wrote one of his finest and saddest tales. In ‘The Burrow’, a solitary, mole-like creature has dedicated its life to building an elaborate underground home in order to protect itself from outsiders. ‘I have completed the construction of my burrow and it seems to be successful,’ the protagonist notes at the outset. Quickly, however, the creature’s confidence begins to wane: how can it know if its defences are working? How can it be certain?

Kafka’s protagonist wants nothing less than complete security, so nothing can be left out of its calculations. In the small world of its burrow, every detail is significant, a possible ‘sign’ of a looming attack. Eventually, the creature begins to hear a noise it believes to be that of an invader. The noise is equally loud wherever it happens to be standing. It would appear, then, to originate within the creature’s own body: the sound, perhaps, of its own heart beating, its own frantic breathing; life happening and ebbing away, while the creature is worrying about something else.

‘The Burrow’ seems to serve as a retrospective commentary upon Kafka’s own life. By the time he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of 34, Kafka had already spent two decades worrying about disease. He took his holidays at convalescent spas, while letters to friends and lovers often amounted to little more than catalogues of symptoms. Kafka attributed all this to what he frequently called his ‘hypochondria’, a condition that, he believed, consigned him to the monastic life of a writer.

Kafka had inherited the view, popular since the Romantic era, that a certain sickliness becomes a writer – an idea that can be traced back as far as Robert Burton, who explained in his compendious (and never-completed) Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) that ‘windy Hypochondriacal Melancholy’ was an ailment of students and scholars. ‘I am taciturn, unsociable, morose, selfish, a hypochondriac, and actually in poor health,’ Kafka wrote in 1913 to Carl Bauer, the father of his fiancée, Felice. What is more, he added, ‘I deplore none of this.’

On the morning that he wrote these words to Herr Bauer, Kafka had been reading the letters of Søren Kierkegaard. He was seeking inspiration for the persona he was cultivating for himself, a holy, invalid litterateur. Hypochondria was inevitable, Kafka explained, for a person whose ‘whole being is directed toward literature’. It was a bombastic claim for a young civil servant employed at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague – one who, at that time, had published only one book: a slim volume of stories that failed to sell more than a few hundred copies. To Felice, he was bolder still: ‘I am made of literature, I am nothing else.’

But Kafka’s hypochondria had a more surprising dimension: his parallel investment in ideologies of physical fitness and wellbeing, with many similarities to the modern cult of ‘wellness’. Throughout his life, Kafka maintained a commitment to the principles of Lebensreform, a cultural movement that was popular among the German-speaking bourgeoisie. Along with an embrace of the virtues of purity and nature, Lebensreformists promoted vegetarianism, abstention from alcohol and tobacco, naturopathic medicines, simple dress, and exposure to sunlight and fresh air. For a person who took these views as seriously as Kafka, Lebensreform informed every aspect of a person’s life: no detail could be spared one’s attention.

On the night of 22 September 1912, Kafka enjoyed what he considered to be his first literary success. In a single sitting, one week after his father Hermann’s 60th birthday celebrations, he composed ‘The Judgment’, a masterpiece of paternal ambivalence. In the dissociative, happy hours that followed, he noted in his diary that writing requires a ‘complete opening out of the body and the soul’. Kafka’s scrupulous attention to his body can offer us insight into his subsequent practice as a writer, the distinctive way he transformed his suffering into literature. For Kafka, hypochondria was not just a state of mind, but a fundamental disposition towards the world, a way of subjecting one’s life and relationships to endless dissection and interpretation.

Ever since he was a boy, Kafka had harboured insecurities about his body. Back then, trips to the swimming baths could be ruined by the sight of his father Hermann’s imposing physique. Kafka’s self-image was confirmed when, as a young man, he was spared military service ‘on account of weakness’.

‘I am the thinnest person I know,’ he told Felice a few years later. That was saying something, he added, for he was ‘no stranger to sanatoria’. In a moment of optimism, Kafka once bought Strength and How to Obtain It (1897) by Eugen Sandow, the founder of modern bodybuilding. Sandow was a source of encouragement to skinny and dumpy males across the continent, with a readership that included Fernando Pessoa, W B Yeats and T S Eliot.

Throughout his life, Kafka was seduced by a variety of different teachers and ideologies of wellbeing. At times, he subsisted off only nuts and berries. He chewed each mouthful of food for several minutes, according to the instructions of one Horace Fletcher. On advice from several disreputable authorities, Kafka went about the cold Prague winter in shirtsleeves, hoping to acquire natural immunity to disease, and he refused to heat his bedroom.

But it was the holistic regime of the Danish fitness guru Jørgen Peter Müller that truly resonated with Kafka. Müller is poorly remembered now, but in the early part of the 20th century he was a global celebrity. His bestselling book was My System: 15 Minutes’ Work a Day for Health’s Sake (1904), a copy of which Kafka kept open at his bedside. My own copy is a reissue from the 1930s, by which time Müller could boast of having sold 1.5 million books, in 26 languages, while having gained the patronage of the Prince of Wales. By 1912, Müller was able to relocate to London, where he opened a high-class fitness institute, first near Piccadilly and then in Trafalgar Square (the building is now home to a Waterstones bookshop).

Most important of all were cleanliness and purity: windows were kept open to disperse ‘pestilential vapours’

Müller was an unlikely role model for Kafka. A pioneer of the modern publicity stunt, he once had a volunteer pull a wheelbarrow full of rocks across his stomach in front of a large crowd. In photographs, he is frequently depicted skiing in his underwear or else submerged in frozen lakes. Müller’s ‘system’ comprised a series of exercises that were mostly aimed at strengthening the abdominal muscles, as well as advice covering virtually every aspect of physical health. Kafka began ‘Müllerising’ (as it was called) sometime around 1910, and followed it for the best part of a decade.

Müller disdained those who believed that ‘sickly looks are an infallible index of an aesthetic and soulful nature’. In fact, Müller directly addressed himself to ‘Literary and Scientific Men and Artists’, urging those who occupy the ‘higher spheres’ not to neglect their physical bodies. In seeming contradiction with the deliberate cultivation of a neurasthenic persona, Kafka also internalised Müller’s message. ‘My mode of life is devised solely for … fitting in better with my writing,’ he told Felice early on in their relationship, as he explained the rationale behind his Müllerising: ‘time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle manoeuvres.’

According to Müller, physical strength was only one aspect of a more complex concept of health. His book advised Kafka on matters such as diet, sleep, dress, temperature control, as well as the proper care of one’s teeth, mouth, throat, hair and feet. Most important of all were cleanliness and purity: windows were to be kept open to disperse ‘pestilential vapours’, and the prescribed ‘15 Minutes’ Work’ included several minutes of bathing and scrubbing (‘skin gymnastics’). According to Müller, the skin was the body’s most important ‘organ’, the threshold between outside and in, and failure to immediately remove the poisonous excretions that accrue there was tantamount to suicide. For Müller, health was not a one-off choice: it was an ongoing task that required constant attention to every aspect of one’s body and environment.

Inspired by Müller, Kafka’s daily routine consisted of waking up and arriving at his office by 8am, before returning home to eat a late lunch and take a nap. He would then do 10 minutes of exercises – ‘naked, by an open window’, as prescribed by Müller – before taking an evening constitutional and eating dinner. Around 10pm, he’d begin his real day’s work: sitting down to write until the early hours of the morning. ‘Then again exercises, as above, but of course avoiding all exertions, a wash, and then, usually with a slight pain in my heart and twitching stomach muscles, to bed.’

If Kafka’s testimony is to be believed, this daily rhythm was essential to his remarkable productivity in this period. In the space of a few weeks at the end of 1912, he wrote the short story ‘The Judgment’, several chapters of the novel Amerika, and then, between November and December, ‘The Metamorphosis’ – among other things, a remarkable story of bodily transformation. The idea for it came to Kafka while he was lying in bed during a period of intense insomnia. He had, he said, ‘an overwhelming desire to pour myself into it’.

His health was ‘deceptive’, Kafka once complained; ‘it deceives even me’

At the beginning of ‘The Metamorphosis’, the travelling salesman Gregor Samsa fails to show up for work. He is understandably preoccupied, having been transformed overnight into an insect. Nevertheless, Gregor fears the arrival of the chief clerk and the insurance doctor, who he knows will accuse him of malingering. According to Gregor’s employers, the sick are ‘workshy’ and ‘simply have to overcome’ their imaginary ailments ‘because of business considerations’.

Similarly, Müller believed that ‘illness is generally one’s own fault’, and wrote about the exorbitant cost to employers and to society of workers who, having paid no heed to their own wellbeing, are taken to spells of absence due to self-inflicted illnesses. The sick were guilty of ‘fraud’.

Kafka knew how pernicious that worldview could be, having witnessed the suffering of workers at the hands of unscrupulous bosses in his role as an insurance official. Nonetheless, the idea that responsibility could yield freedom appealed to him: if physical illness was a choice, then one could simply say ‘no’. His health was ‘deceptive’, Kafka once complained; ‘it deceives even me.’ Müller’s book promised nothing less than a metamorphosis: if Kafka followed its principles, his body would be ‘transformed from a fidgety, hypochondriacal master, to an efficient and obedient servant.’

Kafka’s obsessive dedication to physical wellbeing seemed to go hand in hand with a solitary disposition. But in the summer of 1912, he met Felice at the apartment of their mutual friend Max Brod, the man would go on to become his literary executor.

Felice was an ambitious young secretary who lived in Berlin. A distant relative of the Brods, she was visiting the family en route to her sister in Budapest. Five weeks after their initial encounter, Kafka wrote to her, beginning a long and often frantic exchange of letters. ‘Every one of your letters, no matter how short, is for me endless,’ he wrote to her. ‘I read it down to the signature, then start again, and so it goes around and around in circles.’

Kafka proposed, in writing, the following summer. It was a strange letter, for the most part a litany of reasons why Felice ought to reject him. In place of the ‘incalculable losses’ she would suffer at his side, she stood only to gain a ‘sick, weak, unsociable, taciturn, gloomy, stiff, almost hopeless man.’ Nevertheless, Felice accepted.

He offered to buy Felice a screen so that they could exercise together in the prescribed way

For Kafka, this initiated a period of crisis. He truly did wish to marry Felice. The problem was that he also wished not to marry her, and that these two options were incompatible. For as long as these desires were private, their incommensurability could be contained. Now, ambivalence spilled over into panic. The same relentless attention he brought to his bodily wellbeing became a neverending self-interrogation about his engagement. ‘Everything immediately gives me pause,’ he wrote – every little thing setting off a chain of doubts that went around in circles.

Taking to his diary, he wrote a ‘Summary of all the arguments for and against my marriage,’ weighing his ‘inability to endure life alone’ against his suspicion that the happiness of a shared life would come ‘at the expense of my writing’.

From the earliest days of their courtship, Kafka’s anxieties frequently extended beyond his own body to that of Felice. He would constantly ask about her headaches and chastise her for not taking them seriously enough, as well as for her ‘nerve-wracking’ lifestyle. Kafka implored Felice to begin Müllerising, offering to buy her a screen so that they could exercise together in the prescribed way; days before he sought to break off their engagement, he wrote to tell her about the vegetarian household they would be keeping. By enlisting her into his regimes, Kafka was inviting Felice to enter his little burrow where he hoped that, living together but entirely on his own terms, he would be able to enjoy all the benefits of solitude and companionship.

In June 1914, Kafka and Felice were officially engaged. It was a whole-family affair: the Kafkas and the Bauers together in Berlin. Kafka’s mood that day was funereal. ‘Was tied hand and foot like a criminal,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘Had they sat me down in a corner bound in real chains, … it could not have been worse. And that was my engagement; everybody made an effort to bring me to life, and when they couldn’t, to put up with me as I was.’

The final straw came when he and Felice went shopping for furniture: Kafka was appalled by the fussy, middle-class tastes of his fiancée, which conflicted with the minimalist principles of Lebensreform. ‘The sideboard in particular … oppressed me,’ he recalled two years later; it was like a ‘tombstone’. In fact, hadn’t he heard a threatening noise as they walked into the furniture shop, the toll of a funeral bell?

Kafka was uncompromising: like everything else, furnishing a home was a matter of principle. Nothing ought to be surplus to requirements; his watchword, as ever, was purity. Sideboards, photographs, bedlinen, aspidistras and rugs – to Kafka, all this amounted not simply to clutter, but ‘dirt’.

Kafka’s ‘hypochondria’ was something far more than a fear of illness

A fortnight after these festivities, Kafka wrote a letter to Felice’s friend Grete Bloch, attempting to explain his strange behaviour and ‘obstinacy’. ‘I have to refer everything to my lack of health,’ he explained. ‘If I were healthier and stronger, all difficulties would have been overcome.’ In that case, he would be ‘sure’ of his relationship with Felice; indeed, he would be ‘sure of the whole world’. As it stood, however, he was certain of only one thing: ‘Undoubtedly,’ he suffered from ‘an enormous hypochondria, which however has struck so many and such deep roots within me that I stand or fall with it.’

As this statement makes clear, Kafka’s ‘hypochondria’ was something far more than a fear of illness. It was the way his entire world was made meaningful, every detail significant. Nothing could be taken for granted; everything had to be weighed, viewed from every angle. Big or small, everything was material for the interpretations of a consciousness that was both expansive and pedantic.

Soon after he’d written to Grete, Kafka was summoned back to Berlin. It seems that Felice and Grete had spoken. Felice decided to put an end to things and, alongside her sister and Grete, Felice confronted Kafka in a suite at the Askanische Hof Hotel. Kafka experienced this as a painful humiliation, a blow from which it was difficult to recover. In his diary he would characterise the encounter as a ‘tribunal’.

Back in Prague, Kafka moved into the apartment that had been abandoned by his sister and her husband. The First World War had erupted in Europe the day before. For the very first time in his life, he was living alone. He had achieved ‘complete solitude’, save for a noise: the endless chatter of his neighbours. In his diary, Kafka wrote: ‘In one month I was to have been married. The saying hurts: you’ve made your bed, now lie in it.’

As it happened, over the coming months, Kafka would spend more time at his desk than in bed. In this cold and solitary apartment, burrowed away from a world that was falling apart, he continued the long work of retrospection. Sitting at his desk until five, six, seven o’clock in the morning, he began work on a novel that would become The Trial (though, like ‘The Burrow’, it remained incomplete, and was edited and published by Brod only after Kafka’s death in 1924).

The Trial is the story of a man, Josef K., who is accused of an unnamed crime. He is ruthlessly persecuted and eventually executed by an unknown authority, while being kept in ignorance of his guilt. What he finds unbearable, above all, is this enforced ignorance, and hence the senselessness of the accusation against him: what is K. supposed to have done?

His real hope is that he will find the crime that could make sense of the punishment

It is all too much to bear; as a result, K. turns to writing. Late in the novel, he decides he will produce a written document examining ‘every tiny action and event from the whole of his life, looking at them from all sides and checking and reconsidering them.’ K. knows this will be a long process, ‘an almost endless amount of work’. And so if, ‘as was very likely, he could find no time to do it in the office he would have to do it at home at night.’ In fact, one did not have to be ‘of an anxious disposition’ to view this task with a certain resignation, to suspect that ‘it was impossible to ever finish it.’ Nevertheless, with all this in mind, he begins the endless work of self-examination.

For K., exoneration is not the point. His real hope is that he will find the crime that could make sense of the punishment, and, in making it meaningful, make it bearable. He never reaches this state of enlightenment, however. Kafka’s heroes never do. At the end of the novel, he dies senselessly, ‘like a dog’.

Kafka paused the writing of The Trial to produce a short story on a similar theme, ‘In the Penal Colony’. Here, so-called ‘criminals’ are selected for execution at random, and die by being placed into a machine in which their crimes are etched, repeatedly, into their skin. The officer overseeing this procedure believes that a condemned man ‘deciphers’ his guilt ‘with his wounds’, and therefore dies in a terrible but delectable state of enlightenment. However, putting himself into the machine, the officer does not achieve this meaningful death; only ‘murder, pure and simple’.

After a period of estrangement from Felice, Kafka eventually resumed the relationship at a low simmer. The two became engaged again. Then, in 1917, Kafka had his first attack of tuberculosis. It was an awful scene: one evening he went to bed, only to wake in the middle of the night choking on his own blood. He stumbled to the basin, and then to the window, from where it was possible to see the castle up on the hill. But the blood continued to flow.

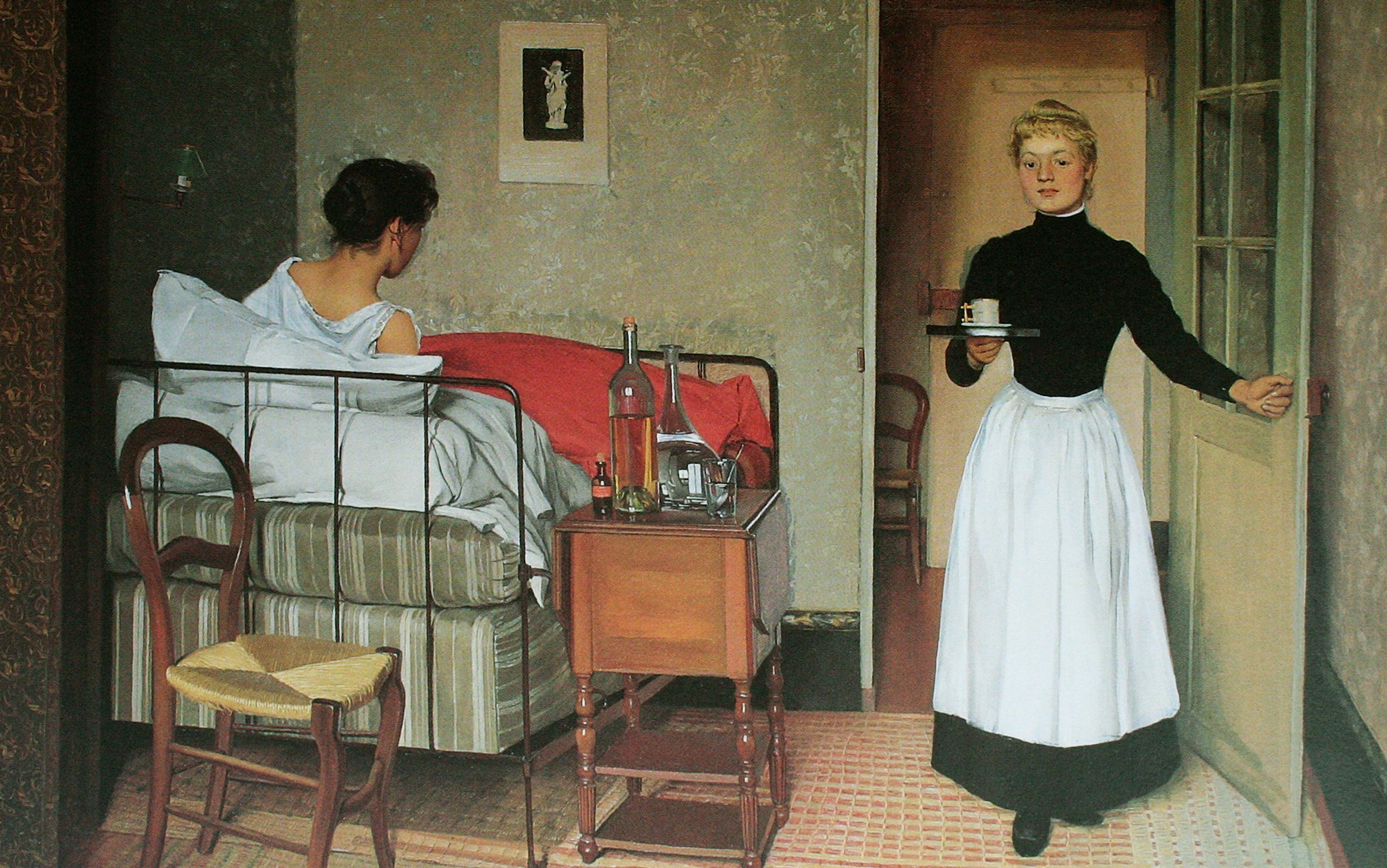

The sun was rising when Kafka finally returned to bed – not unusual for him. Less expected was the fact that he had no trouble falling asleep. Later, the maid appeared and, seeing the mess, offered an unsolicited prognosis: ‘Herr Doktor, you won’t last much longer.’ But for the first time in months, Kafka was calm. He had slept better than ever. Shortly afterwards, he finished things with Felice, putting an end to five years of indecision. But before long he would be engaged once more, having now enlisted a tubercular patient named Julie Wohryzek into his neverending efforts to understand what he wanted.

For those who have been labelled ‘hypochondriac’, the moment of actual diagnosis tends to be an exoneration, the occasion that proves that one was never a hypochondriac to begin with (‘I told you I was sick’). For some people, a diagnosis – however terrible – can thus come as something of a relief, since it heralds the end of the hypochondriac’s endless cycle of interpretation. When Alice James (sister of the philosopher William and the author Henry) was diagnosed with breast cancer, she responded by calling it ‘the most supremely interesting moment in life, the only one in fact, when living seems life.’

It was the lesson he had learned from Müller: illness is one’s own fault

But this was not the reason for Kafka’s calm. His pulmonary haemorrhage had initiated a metamorphosis in him, from le malade imaginare into a bona fide patient. Yet, even now, he continued to refer to himself as a hypochondriac. He explained that years of imaginary ailments had intensified by ‘innumerable gradations’ until ‘it finally ended with a real illness.’ This ‘disease of the lung’, he said, was ‘nothing but an overflowing of my mental disease.’

Some years earlier, Kafka had told Felice that people who got headaches must avoid seeking pain relief. Instead, you had to study your entire life ‘so as to understand where the origins of your headaches are hidden.’ It was the lesson he had learned from Müller: illness is one’s own fault. As he lay in a sanatorium atop the Tatra Mountains, Kafka looked back over his whole life to find the hidden origins of his tuberculosis. The punishment was clear enough. It only remained to find the crime.

Kafka had several theories about the source of his illness, but his favourite was that his tuberculosis had been caused by half a decade of uncertainty about committing to Felice: ‘“Things can’t go on this way,” said the brain, and after five years the lungs said they were ready to help.’ Kafka’s imaginary ailments and his real ailments existed on a single interpretative plane: both were symbolic manifestations of his spiritual condition, and therefore could be subjected to interpretation. Perhaps this is what he meant when he declared: ‘I am made of literature.’ For Kafka, illness was always a metaphor; even as he lay dying, the hypochondriac work of reading body and soul remained forever incomplete.

To read more on wellbeing and creativity, visit Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophy and the arts.