In the winter of 1886, William Alexander Hammond – a famed neurologist and the former Surgeon General of the United States Army – took an enormous amount of cocaine. A reporter from the New York paper The Sun who interviewed him waggishly observed that the doctor had been ‘on a terrific spree for science’. Hammond had experimentally worked his way through as many different ways of taking the drug in as many different quantities as he could devise: he tried fluid extracts of coca (the plant from which pure cocaine is extracted), mixed grains of cocaine hydrochloride into purified wines, and eventually began injecting the drug hypodermically. The injections, he said, gave him ‘a delightful, undulating thrill’. On cocaine, everything felt ‘refined’ and ‘softened’. Hammond became intensely talkative: when he was alone, he would talk to himself at great length. ‘I became,’ he said, ‘rather sentimental and said nice things to everybody. The world was going very well, and I had a favourable opinion of my fellow men and women … I enjoyed myself hugely.’

William Alexander Hammond, c1860-65. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Hammond went on taking the drug in increasing amounts until ‘the sensations became rather painful than agreeable.’ He eventually pushed his tests as high as 18 grains (just over 1 gram) in a single dose, which caused him to become ‘oblivious’ to his own actions. He woke up in bed the next day with no memory of how he got there, and quickly discovered that he had, at some point in the night, decided to thoroughly wreck his own library. After this (and after recovering from a ‘most preposterous headache that lasted two days’) he called a halt to the examination.

He might have been unusually enthusiastic in his experiments, but Hammond’s fascination with cocaine was far from uncommon for a medical professional of his time. In early 1885, The Lancet laconically observed that ‘The medical press is full of cocaine just now.’ By the end of the year, the sheer volume of publications dealing with the substance had become ‘so extensive and so many sided that it is difficult to deal with it summarily’. Cocaine had been chemically isolated decades before, but it had mostly been seen as a scientific curiosity – an ‘obscure’ and ‘useless alkaloid’, as one medical journalist later put it. The substance’s sudden ascent from near-total obscurity to worldwide celebrity was due to a single, remarkable innovation: the discovery that cocaine was the world’s first local anaesthetic.

Thanks to cocaine, it became possible for the first time to eliminate pain without resorting to more powerful (and dangerous) general anaesthetics like chloroform. This sudden breakthrough captivated the public imagination in a way that few substances have, before or since. For many, cocaine seemed to convey the promise of the modern, technologically dynamic 19th century: a quickening new age of scientific revelations, new inventions and marvels on an industrial scale. The story of cocaine between the end of the 19th century and the start of 20th is the story of a slow change from technological wonder to dangerous drug of addiction. It is also a story that illustrates the ways in which individual substances can become loaded with ideological meanings, how those meanings can change as they spread through society, and how our perceptions of particular drugs are intimately bound up with our feelings about the people who use them.

Karl Koller was never to become as personally famous as his friend Sigmund Freud, but he did manage to make cocaine very famous indeed. In 1884, Koller was 27 years old and working as an intern in the eye surgery department of Vienna General Hospital. He was professionally ambitious and hoped that an important-enough discovery might allow him to apply for a position at one of the city’s large and prestigious eye clinics. To this end, he began doing laboratory work on experimental anaesthetics. Both ether and chloroform (the two anaesthetics primarily in use at the time) had side-effects that made them awkward to employ in eye surgery, and Koller hoped that he might make his name by finding a better alternative. It was Freud who introduced Koller to cocaine. Freud – then a similarly young and ambitious medical man – had been ‘toying’ with the idea of using the alkaloid as a stimulant and a treatment for ‘heart disease’ and ‘nervous exhaustion’. He asked his colleague to help him with his experiments, so Freud and Koller began ‘taking the drug by mouth’ and recording its various effects.

Karl Koller, c1900. Courtesy Wikipedia

Towards the middle of the year, Freud left on a month-long visit to see his fiancée while Koller continued the work on his own. He noticed that cocaine had a numbing effect when applied directly to the tongue, and it occurred to him that it might work similarly on the surface of the eye. After successfully anaesthetising first the eye of a frog, then a guinea pig, and then finally his own eye, Koller wrote up an account of his results and handed them to a colleague to present at an upcoming conference in Heidelberg (since Koller was too poor to afford the trip there himself). The public reaction was electric. Decades later, Koller recalled that ‘knowledge of the new remedy spread quickly, and in looking over the medical and the lay press of the time, one will encounter a perfect flood of communications on cocaine and local anaesthesia.’ On hearing the news, one of the presidents of the British Medical Association asserted that: ‘In the discovery of cocaine, a new era seems to have dawned.’

Freud had jokingly invested his friend with the nickname ‘Coca Koller’

As for Koller, though he certainly achieved international renown from his discovery, the dawn of cocaine’s new era coincided with the arrival of a less fortunate interval in his own career. In January 1885, while medical papers were still full of news of his success, he got into an argument with a man named Friedrich Zinner, another surgical intern at Vienna General. Beginning with a technical disagreement over a patient’s injured finger, matters escalated until Zinner called Koller an ‘impudent Jew’ (or possibly a ‘Jewish swine’ according to Freud’s recollection) and Koller replied by punching Zinner in the face. Both men were medical lieutenants in the army reserve, so Zinner challenged Koller to a duel. When they met five days later, Koller emerged from the duel unharmed, but he left his opponent with two deep wounds. The Vienna public prosecutor was obliged to bring charges against both men, and a criminal case meant that Koller was bound to resign his position at the hospital. He spent the next few years living in the Netherlands before emigrating to New York in 1888. In the US, he had better luck capitalising on his renown, opening a thriving ophthalmological practice and becoming the first winner of the Lucien Howe Medal for outstanding achievements in eye medicine.

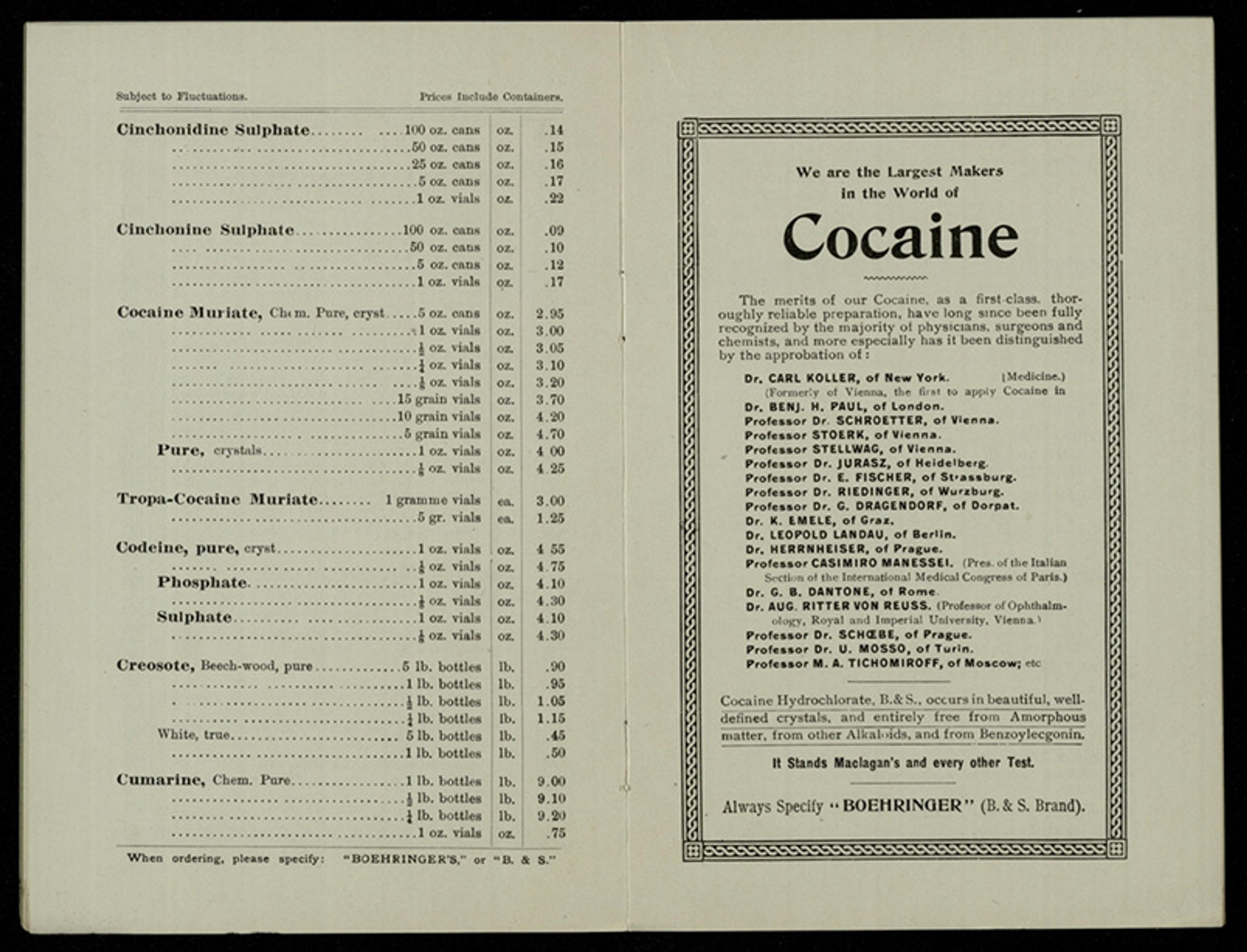

Advertising pamphlet for the Boehringer company, 1897. Courtesy the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia

When news of Koller’s discovery had first begun to spread, Freud had jokingly invested his friend with the nickname ‘Coca Koller’. As the 19th century wore on towards the 20th, however, cocaine was destined to dramatically outgrow both its discoverer and the relatively specialised applications he had envisioned for it.

Part of the reason cocaine captured the Victorian imagination so vividly was because of how well it performed in comparison with existing anaesthetics. Chloroform had been in use for almost 40 years by the time that cocaine appeared, but doctors and patients alike were still ambivalent about its use in surgery. Accidents and deaths under general anaesthesia were comparatively rare but consistent enough that, as one practitioner observed: ‘There are many people who dread chloroform so much, that they decline to take it, unless practically coerced.’

Cocaine looked like an obvious answer to this problem, at first. ‘With a solution of cocaine at hand,’ wrote the St James’s Gazette excitedly, ‘chloroform and ether may be dispensed with.’ In this light, cocaine appeared to be the ‘ideal anaesthetic’ – safe, effortless and effective. The discovery of the drug came to be seen as almost epoch-making: it appeared to mark the advent of a new age where modern, technological medicine would sweep away pain and poor health altogether. Reporting on the discovery, Chambers’s Journal called cocaine ‘a wonder of the age’. The paper wrote: ‘Cocaine has flashed like a meteor before the eyes of the medical world, but, unlike a meteor, its impressions have proved to be enduring.’

As cocaine’s meteoric ascent continued, its price also began to rise. The more that enterprising medical practitioners rushed to obtain samples of the alkaloid, the more demand began to outstrip supply until, in late 1884, the value of cocaine reached £32 an ounce (around £3,300 or $3,680 an ounce today). In the US, some suppliers in major cities could ask as much as $300 an ounce. For a while, the white powder was more valuable than gold.

In making tattooing painless, cocaine had also managed to make it seem refined enough for polite society

Once supply caught up with demand and the cost of the drug levelled off, cocaine quickly found itself applied to all manner of uses, both exotic and everyday. Outside the operating room, the most common use of cocaine was as a cold and flu remedy. By the 1890s, Burroughs, Wellcome & Co supplied a portable cocaine nasal spray for congestion that was ‘so small as to be easily carried in the waistcoat pocket’. For those who preferred to mix their cold medicines at home, newspapers provided recipes compounded of cocaine, ground coffee, menthol and powdered sugar, which were finely ground together and ‘used like an ordinary snuff’. Cocaine lozenges were regularly advertised as the best thing an anxious traveller could get for seasickness. The same lozenges were also frequently touted as the ideal treatment for ‘the sickness of pregnancy’. Hay fever and tickly coughs also yielded to tablets of cocaine, while tubes of cocaine toothpaste promised to remedy the pain of toothache and bleeding gums. And for those who suffered from less definitively physical maladies, there were products like ‘Neurogene’: a ‘compound syrup of cocaine’ that offered relief to ‘Speakers, Singers, Athletes, Business Men, and all who suffer from Brain Fag, or Nervous Debility’ – price 2 shillings and 9 pence, or just over £11 ($15) today.

Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

One unforeseen consequence of cocaine was to accelerate the fashion for tattoos. Both Edward VII and the future George V had been tattooed on overseas visits to Jerusalem and Japan respectively, and this had sparked off something of a craze for the practice among the British public. Tattooing was a somewhat fraught process by the standards of the time, though. The willingness to endure pain in the interest of nothing more substantial than personal decoration was often thought to betray something coarse – even brutal – in the temperament of the tattooed. But cocaine offered an effective solution to this issue. One paper covering the trend wrote: ‘Some years ago [tattooing] was a very painful operation, but the discovery of cocaine has made it a painless one.’ In making tattooing painless, cocaine had also managed to make it seem refined enough for polite society.

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, by Carlo Pellegrini, 1873. Courtesy and © the National Portrait Gallery London

Armed with cocaine, a new breed of celebrity tattoo artists began to emerge. One of the most famous was Sutherland MacDonald of Jermyn Street in London, who – when a journalist asked if his clients were required to suffer much pain in the execution of his designs – confidently responded: ‘Not at all, because I inject cocaine under the skin at the part upon which I am going to operate, and use more cocaine directly the effects of the first injection have passed away.’ For those desirous of learning the art themselves, it was possible to purchase a full home tattooing kit, comprising ‘a complete set of tattooing instruments, needles mounted in ivory handles, non-poisonous inks of various colures, and a tiny bottle of cocaine to render the operation painless’, all neatly enclosed in a handsome ‘Russia leather case’.

In the years after Koller’s discovery, cocaine had become well established in its role as both a technological and fashionable drug à la mode. The substance was encircled with an aura of newness and transformative potential. Journalists rhapsodised over the way in which the drug seemed – like a modern Athena – to have ‘sprung into existence fully armed’: it was at once a vital tool in ‘the armoury of the modern scientific surgeon’ and ‘the prized possession of millions’.

Cocaine even found its way into the hands of one of the most famous fictional characters of the age: Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. The Sign of Four (1890), the second of the Holmes novels, begins with its hero rolling up his shirt sleeve and injecting himself with a ‘seven per-cent solution’ of cocaine. Doyle had trained as a doctor himself and was well aware of cocaine’s popular associations with modernity and innovation. For Doyle, giving his character a cocaine habit was a way to quickly convey to his readers that Holmes was a thoroughly modern man – energetic, specialised and scientifically knowledgeable. Strange as it might seem to us now, more than a century after cocaine’s criminalisation, the first Victorian reviewers were fascinated by this facet of Holmes’s personality. The Graphic newspaper thrilled at the detective’s ‘genius and energy’. Holmes was, the reviewer enthused, a ‘first-class’ detective, ‘who must either be engaged in unravelling a first-class mystery, or in consoling himself for the want of one with cocaine.’

Doyle decided to dispense with Holmes’s cocaine habit for good

As time wore on, however, and Doyle’s detective became ever more popular, his cocaine use was to become a focus for new anxieties building around the drug. In 1901, John Wyllie, a professor at Doyle’s old medical school, the University of Edinburgh, described how he had one day been called to see a sick young man. As Wyllie entered the house, his patient’s sister ran to him, crying pitifully that: ‘It’s all that horrid book!’ Wyllie went on: ‘Inquiry elicited the fact that the patient’s favourite reading was Sherlock Holmes. The young man was in a very low state, and his tell-tale arm was dotted with hypodermic punctures. His admiration for the most popular of paper detectives had betrayed him into the cocaine habit.’ Wyllie’s experiences were published in both popular and medical papers. The British Medical Journal’s report wound up with the vague but nevertheless pointed suggestion that authors who cavalierly encouraged their readers into the ‘baleful spell’ of the drug habit might have ‘much to answer for’.

William Gillette as the title role in Sherlock Holmes (1899) on Broadway at the Garrick Theatre, New York City. Courtesy the Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library

With the coming of the 20th century, popular perceptions of cocaine began to shift in subtle but important ways. With the passage of the years, cocaine was still seen as a technological triumph, but this was balanced against a wider sense of the dangers that might come from its overuse. Writers who had at first been intrigued and excited by Holmes’s ‘seven per-cent solution’ were increasingly cautious of being seen to advocate for a ‘dangerous drug’. Doyle decided to dispense with Holmes’s cocaine habit for good. ‘The Adventure of the Missing Three Quarter’ (1904) begins with Watson recalling how he had worked ‘for years’ to gradually wean his friend off the ‘drug mania which had threatened once to check his remarkable career.’ This passage marks the final word on cocaine in the Holmes canon. Henceforward, the drug was to be emphatically relegated to the detective’s past – a tragic and dangerous misadventure from which he had been rescued by Watson’s conscientious intervention.

Doyle’s reframing of Holmes’s cocaine use illustrates the ways in which perceptions of cocaine were changing in the early years of the new century. When Doyle had first conceived of his detective, cocaine had been regarded as a ‘modern panacea’ – a tangible proof that science could better the human condition – and its use marked Holmes as a modern, technologically engaged individual. By the early 20th century, though, these associations had begun to shift as the substance became much more directly tied to the threat of addiction and degradation.

Legislative controls on cocaine first started to appear in the 1910s. In Britain, the Defence of the Realm Act was introduced in response to the demands of the First World War, and in 1916 it was used to restrict the sale of the drug to specific ‘authorised persons’ such as doctors, surgeons and dentists. Under the act, cocaine could now be obtained by members of the public only with a doctor’s prescription. These restrictions remained in place until after the war, when they were permanently codified into law through the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920. In part, these laws were a response to the genuine dangers of cocaine addiction – to the risks that cocaine might pose to naive or over-enthusiastic individuals like Wyllie’s unfortunate patient. But they also reflected the broader social and racist prejudices of their time.

As cocaine use became more widespread, it began to permeate out of the relatively closed circle of the affluent, white middle and upper classes. For a white, wealthy, socially established man like William A Hammond to experiment with cocaine and its pleasures was acceptable. At worst, it might be a little comical. The same experiences could be made to seem much more threatening when they were taken up by the poor, by women or by people of colour.

A double standard developed around cocaine in the period leading up to its criminalisation

In 1914, The Lancet and various popular newspapers in the UK republished an article by the doctor Edward Huntington Williams on cocaine in the southern US. Williams claimed that any Black man who took up the cocaine habit was ‘absolutely beyond redemption. His whole nature is changed by the habit. Sexual desires are increased and perverted; peaceful men become quarrelsome and timid ones courageous.’ Sidney Felstead, author of The Underworld of London (1923), claimed to be similarly appalled by how often ‘some pleasure-sated girl dies from an overdose of cocaine or morphia, supplied to her by of some black or yellow parasite.’

These remarks illustrate the double standard that developed around cocaine in the period leading up to its criminalisation. The sense of newness, of transcendent modernity that cocaine imparted to William A Hammond or to Sherlock Holmes was not extended to everyone. The stigmatisation of the drug as an agent of danger and perversity reflected already-existing prejudices against those minorities, and the laws that were enacted to control it reflected (at least in part) the desire to control those same people.

Over the decades, cocaine had transitioned from a wonder of the newly technological and industrial Victorian age to a frightening and corrupting source of addiction. The story of cocaine illustrates not only how much our perceptions of specific drugs can shift over time but how readily drugs can capture and condense our emotions. Cocaine was always a drug peculiarly surrounded by fantasies: hopes, fears, optimism and anxiety. Describing its history reveals the degree to which our fantasies and fears about drugs shape, and are shaped by, our fantasies about their users.