When I met the retired ballerina Toni Bentley at a reception in 2008, and she found out that I am a historian and philosopher of anatomy, she told me enthusiastically about how she had boiled her hip bone in a soup pot. Well, bones, really. The surgeon who had replaced Bentley’s dance-scarred, arthritic right hip with an artificial one had taken it out in pieces, as removal requires. In advance of the procedure, Bentley had convinced him to give her back the parts. The surgeon thought the request strange, but Bentley later recalled: ‘I suppose I thought that in keeping the bone after it was removed I was losing less somehow.’

Once Bentley got the chunks home, floating in a Tupperware container of fluid, she had to get the fleshy bits off, and dry out the skeletal remains; she wanted to be able to lay out her bones in the plain air. Not sure how to do this, she dialled a local taxidermist. He explained in a cheery voice that this was an easy DIY project. At his instructions, she boiled her bones in water for an hour, drained them in a colander, soaked them in cold water for half an hour, drained them again, immersed them in a solution of bleach and water, and then let them dry in the sun.

As someone who has spent a fair bit of time hanging out in anatomy museums, I found Bentley’s tale perfectly delightful. I sensed that the third person standing with us at that reception didn’t. Perhaps it was because a waitress kept coming around to offer us bits of meat on a toothpick.

For my part, I could very well understand Bentley’s instinct to keep this relic of her days as a ballerina – her ‘battle wound’, as she has called it. It reminded me of how, after a particularly harrowing series of tooth extractions, my son would occasionally gaze into the plastic bag of blood-stained shards given to us by his oral surgeon. Or how Inga Duncan Thornell, an astrologer and hypnotherapist in Seattle, opted to incorporate her double mastectomy scars into a lush bra-shaped tattoo reminiscent of a Tiffany window. What is a good scar but proof of survival? What is a rich life but an album of wounds?

Indeed, Bentley’s story recalled that of Daniel E Sickles, known to legal historians for temporarily losing his mind, but known to us medical historians for permanently losing his leg. In 1859, Sickles killed his wife’s lover in a fit of jealous rage but convinced a jury to acquit him on the grounds of ‘temporary insanity’ – the first successful use of this legal device. Four years later, Sickles found himself serving as a major general in the Union Army at the Battle of Gettysburg. There, his lower right leg was shattered by a cannonball. Immediately after the injury, Sickles is said to have calmed the horse that he was riding, and then also his troops. He was taken off the field smoking a cigar.

To save Sickles’s life, medics applied a tourniquet and then amputated the wounded leg just above the knee. The mangled limb was then sent on to the Army Medical Museum, an institution established only the year before. The mission of the museum was to have army medics collecting and sending back from the field ‘specimens of morbid anatomy together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed’. Presumably, the museum staff prepared the bones in a similar fashion to Bentley, and Sickles’s leg bones ended up displayed next to a cannonball. For years afterwards, on the anniversary of Gettysburg, the major general visited his leg.

Sickles’s story is historically exceptional, and not just in the obvious way: most people whose parts or whose family members (or whose family members’ members) have landed in anatomy museums have not been aware of where they went. When I worked at Northwestern University’s medical school in Chicago, we scholars in the medical humanities and bioethics programme, together with the anatomy faculty, struggled with the fact that most of the foetal and newborn specimens in our school’s private collection were probably taken and preserved without their mothers’ knowledge or consent.

There was one particularly disturbing story attached to a baby born in 1945 with one eye, a ‘cyclops’. After the baby’s death, a medical student was sent to get the body by his mentor and, while transporting it back, the student supposedly dropped it on the El train. Now we had the body at Northwestern in a jar.

These kinds of stories were why I was more than a little worried when Deb Costandine, a Minnesotan visual artist, asked me to help her figure out what her stillborn conjoined twins had looked like when they had emerged from her, three decades earlier. Costandine and I had met at the museum that housed Sickles’s leg, at a panel on the art of disability. As I learned from her, the doctor had not let Costandine see her babies, presumably because they were of a particularly unsettling conformation – one skull contained within another, with two otherwise complete bodies emerging just below the neck (a type of conjoinment that’s not viable).

Costandine told me her twins were buried in a grave she visited. Still, it was only after I researched the history for her and failed to find them in any anatomical collection that I breathed a hard sigh of relief; I knew there are a lot of dead conjoined twin babies in a lot of museums.

As I did the work for Costandine, I could not stop thinking of Minik Wallace, an Inuit boy brought from Greenland with kin, including his father Qisuk, to be studied by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History in New York at the turn of the 20th century. When Qisuk died in New York, Minik wanted his father to be given a proper Inuit burial. But the museum scientists wanted to keep Qisuk’s body for study. So a fake burial was staged to convince Minik he had gotten his way, and eventually Qisuk’s skeleton was put on display in the museum. The whole distressing history is told in Give Me My Father’s Body (1986). Its author, Kenn Harper, later successfully agitated for the remains of Qisuk and three others stored at the museum to be sent to Greenland for traditional burial.

In the history of anatomy, not every body has enjoyed equal rights. The poor, the criminal, the ‘abnormal’, those deemed as being of ‘lower’ races – these are the people whose flesh and blood have disproportionately been dissected and collected by medical students, doctors and scientists. Even if, like me, you are very pro-science, it’s hard to look at the history of anatomy collections without feeling Harper’s urge for some modern ethics, like applying a balm to festering social wounds.

Minik Wallace in New York in 1897. Courtesy Wikipedia

And the story of Minik and Qisuk is hardly unique. ‘The early history of museum-collecting of Native American remains is replete with horror stories,’ writes Douglas Preston, in the Smithsonian magazine. ‘In the 19th century, anthropologists and collectors looted fresh Native American graves and burial platforms, dug up corpses and even decapitated dead Indians lying on the field of battle, and shipped the heads to Washington for study.’

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, passed in 1990, finally has provided a clear legal means by which Native American tribes can take back the remains and certain artefacts of their kinfolk. The law comes with built-in irony, though. In some cases, to make a claim on a body, Native American groups need scientists to demonstrate a clear connection between them and the relics.

As Preston records, this played out in an especially interesting way in the case of Kennewick Man, a 9,000-year-old skeleton found in Washington State in 1996. Not long after the remains were found, the US government started moving to hand over the remains to a coalition of Columbia River Basin Indian tribes who believed the skeleton to be that of their ancestor. Scientists sued to stop the loss to science.

Ultimately, the judge in the case ruled that the government had failed to show ‘that Kennewick Man shares special and significant genetic or cultural features with presently existing indigenous tribes, people, or cultures’. That’s because the scientists hadn’t been permitted their study; the scientific evidence the Native American tribes needed would be lacking as long as the scientists were denied access.

Having won the case, scientists have since been able to analyse the skeleton. They concluded, initially, that the modern tribes living in the region are not descendants of Kennewick Man. However, the tribes maintained they are, and it’s a claim that recent, more sophisticated DNA testing supports. Of course, all this raises the question of what exactly it means for anybody today to be ‘related’ to a skeleton buried 450 generations ago.

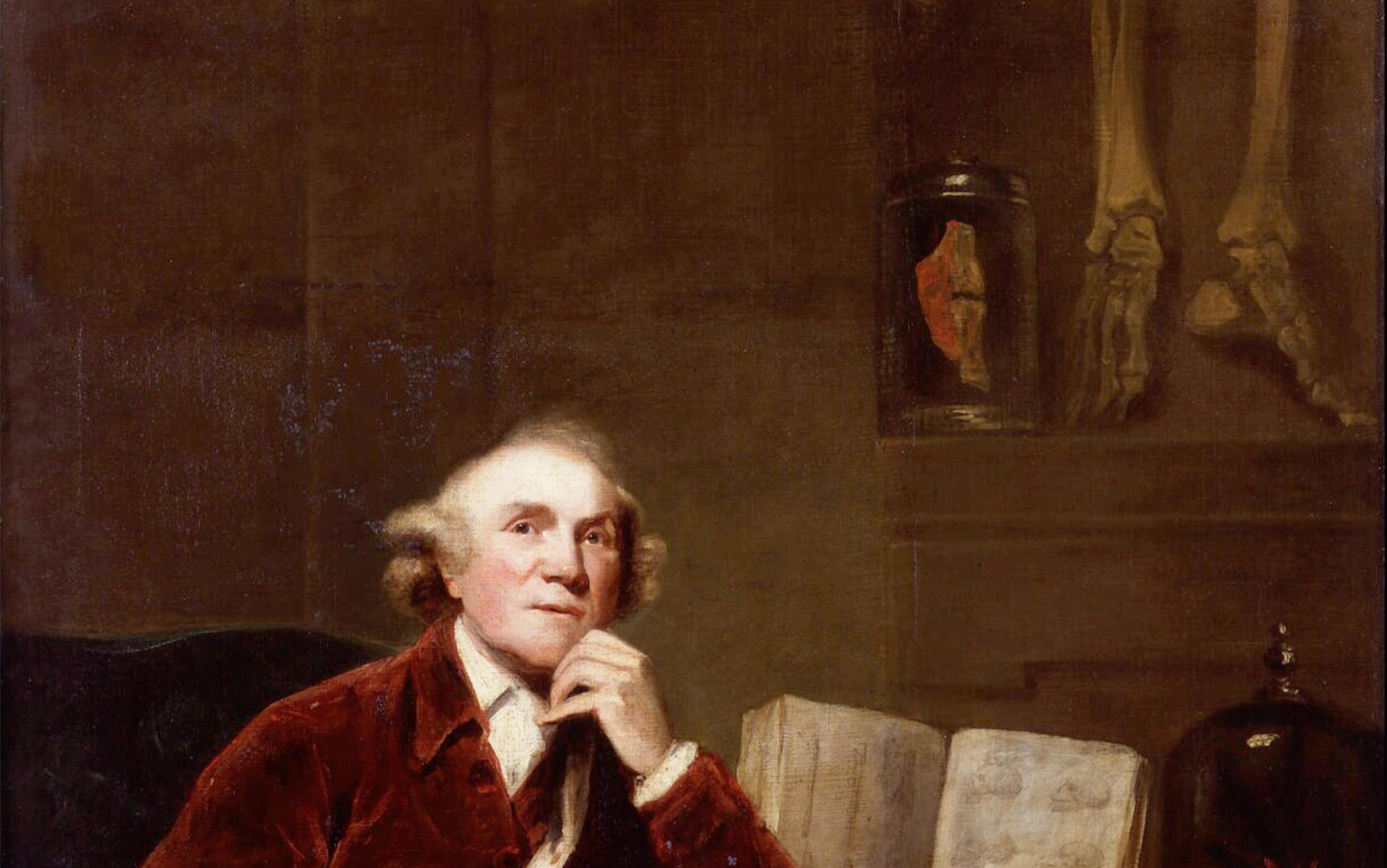

I myself ran into these thorny questions – of who stands as a relation, and who counts as a legitimate defender of whom – when, like Harper, I became obsessed by a museum skeleton obtained under ethically pungent means. This was the skeleton of Charles Byrne, known colloquially as the Irish Giant.

Like a lot of folks with gigantism in the 18th century, Byrne used his anatomical abnormality to make a good living exhibiting himself to the curious. When he died in England in 1783 at the age of 22 and the height of almost eight feet, Byrne left a will stipulating that his money should be used to bury him at sea. His goal was to not be anatomised, something he’d have known happened to people whose bodies were objects of curiosity.

Why did Byrne want to avoid being anatomised? That’s not entirely clear. Perhaps he knew that most people who ended up on anatomy tables were common criminals, unlike him. Perhaps his Christian faith impelled him to keep his body whole for the resurrection.

Whatever his reason, Byrne didn’t get his way. The undertakers sold his body to the highest bidder, who happened to be the famous anatomist John Hunter. Hunter dissected Byrne, wrote his scientific report, cleaned the bones, and put the skeleton in what is now the Royal College of Surgeon’s Hunterian Museum in London, where admission is free, ‘but a donation of £3 per person is encouraged’.

The way science and medicine move forward is to take charge of people’s bodies in ways that we would otherwise find objectionable

I don’t recall whether I made a donation when I was in London in 1998 for a conference and dragged an academic friend to see the Irish Giant. When my friend read, on the skeleton’s glass case, the museum’s somewhat boastful story of how they got Byrne’s bones, his face dropped. He asked me why I wasn’t profoundly disturbed by all this. At that point, early in my career, I guess I had simply been too wowed by the history to think much about the ethics – or to think much about what this display said to visitors about surgeons’ attitudes towards people’s wishes.

After the trip, my friend (a bioethicist) kept sending me notes urging me to ‘Free the Irish Giant!’ So in 1999, I wrote to the Keeper of the Collections to ask why the museum wasn’t following Byrne’s wishes. Eventually, they asked me on whose behalf I was making my request. Translation: unless I could claim some relation to Byrne, I would be ignored. There was no way I was ever going to convince them Byrne and I were of the same tribe.

On the one hand, I appreciated the Royal College’s general desire to keep ‘for science’ remains that might be of special interest. Sometimes, the way science and medicine move forward for the general good is to take charge of people’s bodies in ways that we would otherwise find objectionable. This happens, for example, when someone dies mysteriously or from a suspected contagious disease, and it is in the public’s best interest to subject the body to study and sometimes to keep parts. Full burial or cremation (or other disposal) in such cases may be denied or delayed in violation of the wishes of the deceased and surviving loved ones.

On the other hand, come on. Byrne’s case is clearly an especially egregious example of medical taking, one that still feels primarily about ever-expanding medical authority announcing its power over the rest of us – particularly those of us whom medicine has declared somehow inferior. There was and is nothing so special about Byrne’s remains that justifies overruling his explicit wishes. Gigantism does not represent a public-health emergency, and Byrne’s was not a case of suspicious death. There are plenty of giants’ remains to answer basic scientific questions about the condition.

But historians of anatomy aren’t supposed to request the burying of museum specimens. It marks us as traitors, even if – as in my case – we are motivated by a desire to keep science and medicine healthy. As word got around of my petition to the Royal College, the message was conveyed to me that certain curators and anatomists were not amused.

When I found myself in overt discussions on the matter, I pled that Byrne was a special case: he had specifically indicated that he wanted to be buried at sea, and disrespecting his wishes seemed bad for medicine and science. It wasn’t as if I was suggesting we bury every body we weren’t sure about. As I found myself repeatedly saying, I understood fully why the Hunterian Museum’s protectors, like Kennewick Man’s scientists, wanted to keep these specimens available for research to the greatest extent possible.

The generation of new knowledge is how we go forward, and we need bodies for that. While it is impossible to read Rebecca Skloot’s account of what happened to Henrietta Lacks’s cervical cancer cells after her death in 1951 without feeling sympathy for the Lacks family, surely it is also impossible not to recognise the important research that came out of the decision to collect the HeLa cells and grow them? Science needs to have a lot of power if the public is to benefit from it. And is it really so disturbing, as some readers of Skloot’s book have suggested to me, that Lacks’s cells’ descendants ended up all over the world?

Maybe it’s because I’m an atheist ex-Catholic that I find it difficult to relate to people who are highly ritualistic and dogmatic about how remains are treated. I find it baffling that humans will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars trying to recover the remains of people we know are dead at the bottom of the sea. I find it maddening that Theresa Stack was for 15 years denied a Catholic funeral mass for her late husband because there were no known remains of him. Fire Battalion Chief Lawrence T Stack had died at Ground Zero on 11 September 2001. Only this year, when his family realised there was still a blood sample from him – taken back when he had offered himself to a stranger as a possible bone-marrow donor – was the family able to provide just enough of him to a priest to have their mass.

Yet.

Yet when I think of the being that once lived inside me, and now lives outside – when I look in on him after school and find him in some small variation of his daily ritual, headphones on, eating chips, reading his favourite web comic, listening to Beethoven – it is suddenly impossible to imagine every cell of his body not mattering to me, even into death. When he is away at summer camp, I sometimes visit the curls of his blond baby hair, stored in a folded piece of paper in a small cabinet of my desk.

One thing science has taught us is just how much kinship – flesh – matters to humans. (A lot.) But we didn’t really ever need it to teach us that.

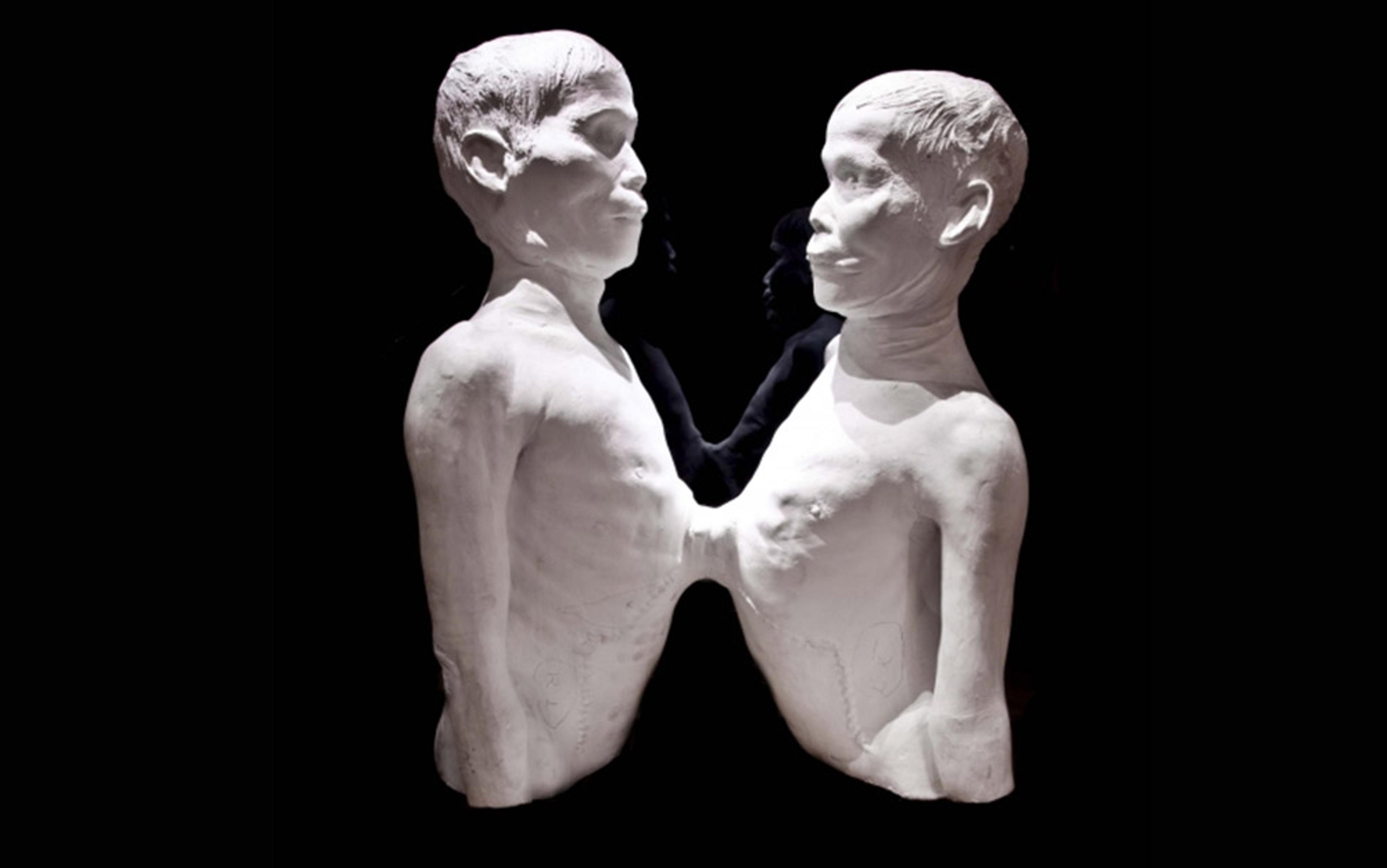

Chang and Eng Bunker’s widows didn’t want to give away their husbands’ bodies after death, even when offered large amounts of money, even though they were left with many children to support. But the College of Physicians of Philadelphia convinced them it was ‘a duty to science and humanity that the family of the deceased should permit an autopsy’, so the widows allowed the postmortem on the condition that the band between the brothers not be cut.

Chang and Eng had been known colloquially as ‘the Siamese Twins’ because they were born in 1811 in the land then called Siam – now Thailand. (The term stuck in pop culture for all later-born conjoined twins.) Connected by a band of skin, muscle and a bit of liver, the two made a fortune exhibiting themselves around the world. Eventually, they ended up settling down in Mount Airy, North Carolina, as Christian gentlemen farmers and slave owners. Chang married Adelaide Yates and had 10 children. Eng married Adelaide’s sister Sarah and had 11. The descendants now number more than 1,000.

Death cast of Chang and Eng Bunker at the Mütter Museum, Philadelphia

If you go to the museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia – the Mütter Museum – today, you can see the conjoined livers of Chang and Eng displayed right below the plaster deathcast the college made of their bodies while they were briefly in its possession. It isn’t clear if the Bunker widows knew that the livers would be taken, no less displayed. One of Eng’s descendants asked me, years ago, if I could help her figure out if there had, in fact, been permission from the Bunkers. She had been to the museum and found it a little strange to have people making fun of her ancestors’ organs. Not disgusting or upsetting or anything – just strange.

The research I did to try to find out the answer to the descendant’s question would have upset the late, great curator of the Mütter Museum, Gretchen Worden, who had not so much a joie de vivre as a joie de morte. With her upbeat nature and fascination with the strangeness of humanity, Worden had become a friend to me and pretty much everyone else in the anatomy business, as well as to the Bunker descendant who had asked me about the livers. Not long after Worden’s early death at 56, as I sat researching Chang and Eng’s autopsy in the library on the floor above where her cluttered office had been, I pictured Worden’s ghost glaring at me, knowing what she’d think of my working on something that might lead to her famous museum specimen being taken. Science must be in charge!

But after Worden died, both the Bunker descendant and I wondered why her own body had apparently been cremated. It made us feel a little less weird about looking into the livers over which Worden had lovingly presided for decades. In any event, I never did figure out the answer to the descendant’s question. Digging around the family’s archives in North Carolina and at the Philadelphia college turned up many interesting documents, but nothing near-conclusive about where everyone thought the livers should end up.

Of course, history might yet turn up something that tells us the answer. That’s the thing about science, including social science – it’s never done. I asked the descendent what she’d want to do if we did find evidence that the Bunker widows explicitly did not want the livers kept by the college. She laughed and said she wasn’t at all sure. Should it be buried, she asked me rhetorically, at the gravesite containing the bodies, in Mount Airy? Should it be passed around the hundreds of living descendants, displayed on various mantles around the country in turn?

I pictured an old conjoined liver treated like the Stanley Cup.

Steadfastly retaining our parts is one way that the medical profession marks its global power over all patients’ bodies

I’ve come to realise that passing around a famous family organ seems weird not because it’s a human body part, but because nowadays medical science has won: most people are convinced that scientists and their helpers are the only ones who should keep organs and other excised tissues, with the odd exception of things such as teeth and hair, the uninteresting parts with which doctors don’t really deal. But, as a historian, I can tell you that the firmness of this cultural attitude is relatively new. When I was a kid in the 1970s, a lot of people in my suburban New York neighbourhood had parts of themselves in jars or boxes at home – tonsils, gallbladder stones. They did not need to leave home to visit their appendices.

This shift in attitudes about our parts is probably partly due to our post-AIDS generalised fear of tissues causing contagion – although the fact is, so long as you treat human bodies carefully, as you would the meat, bones and stones from any other animal, you’ll be okay. I suspect, these days, doctors and especially hospital risk-management teams also don’t want people going home with their parts because it would seem to invite the potential for catching a medical mistake that otherwise would go unnoticed. Tissues removed now sometimes pass through the pathology department but almost always end up in red medical waste bags, where lawyers can’t see them.

It’s worth realising that there’s also a symbolic performance at work when one is understood to be globally obligated to hand over one’s parts simply by entering a clinic. Put plainly, steadfastly retaining our parts is one way that the medical profession marks its global power over all patients’ bodies – it’s the profession’s way of saying: ‘We’re in charge here.’ In many states, automechanics are required by law to offer to return to you the parts they remove from your car. There is, to my knowledge, no law requiring physicians to do the same; on the contrary, when you sign many medical consent forms, you explicitly relinquish your rights to your tissues or any future uses of them.

I would wager that, even if the forms didn’t spell it out, most people would just assume patients have no rights to removed tissue. The body belongs to medicine and science. And of course, in most cases today, people are just as happy to have physicians keep what they take off or out. Rarely do people feel ambivalent or outright cheated. In some cases, they understand that they might be helping medical progress. People’s parts helping other people. Nobody does a 5K run for the cause, but it is a powerful way we all quietly tithe towards medical progress.

And medical science has progressed. While I still wish the Royal College would bury Byrne’s skeleton, I happily acknowledge that, overall, the science that has been conducted on human flesh has contributed to what the physicians and anatomists of Hunter’s time could only dream: preventing diseases such as measles, curing diseases such as testicular cancer, replacing worn-out joints such as Bentley’s.

Standing on the shoulders of giants, so to speak, is how we have ended up with such moving stories as of the bride Jeni Stepien in Pennsylvania, who in August was escorted down the aisle by Arthur Thomas, a man alive thanks to the bride’s late father’s heart.

‘I felt wonderful about bringing her dad’s heart to Pittsburgh,’ Thomas told The New York Times. He added that, had he had to, ‘I would’ve walked.’

His legs, I guess, are still pretty good.