Did you attend a public school in the United States and perform in a school play, take field trips, or compete on a sports team? Did you have a favourite teacher who designed their own curriculum, say, about the Civil War, or helped you find your particular passions and interests? Did you take classes that were not academic per se but that still opened your eyes to different aspects of human experience such as fixing cars? Did you do projects that required planning and creativity? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then you are the beneficiary of John Dewey’s pedagogical revolution.

Dewey put forth the philosophy of education that would change the world in Democracy and Education, a book that turns 100 this year. Dewey’s influence is far-reaching, but his pedagogy has been under assault for at least a generation. The United States Department of Education report A Nation at Risk (1983) signalled the rise of the anti-Dewey front, under the somewhat misleading name of the ‘education reform’ movement. The report warns that other countries will soon surpass the US in wealth and power because ‘a rising tide of mediocrity’ engulfs schools in the US. The problem, according to the report, is that US education is ‘an often incoherent, outdated patchwork quilt’. The education reform movement aims to replace that ‘patchwork quilt’ – mostly made by local school boards, teachers and parents – with a more uniform system based on national standards.

The political right has often led the charge against Dewey’s legacy. In 1897, Dewey described his ‘pedagogic creed’ as ‘individualistic’ and ‘socialistic’ because it sees the need to nurture each child’s unique talents and interests in a supportive community. For both the business community and traditional-values conservatives, Dewey’s pedagogy fails to train workers, and inculcates liberal, even socialistic values. The US Chamber of Commerce and the Charles Koch-funded conservative think tank the Heartland Institute, to take just two examples, have tried to purge the US education system of its progressive elements. Similarly, in 2002, President George W Bush signed the No Child Left Behind act, an anti-Deweyan measure requiring states to implement test-based education reform.

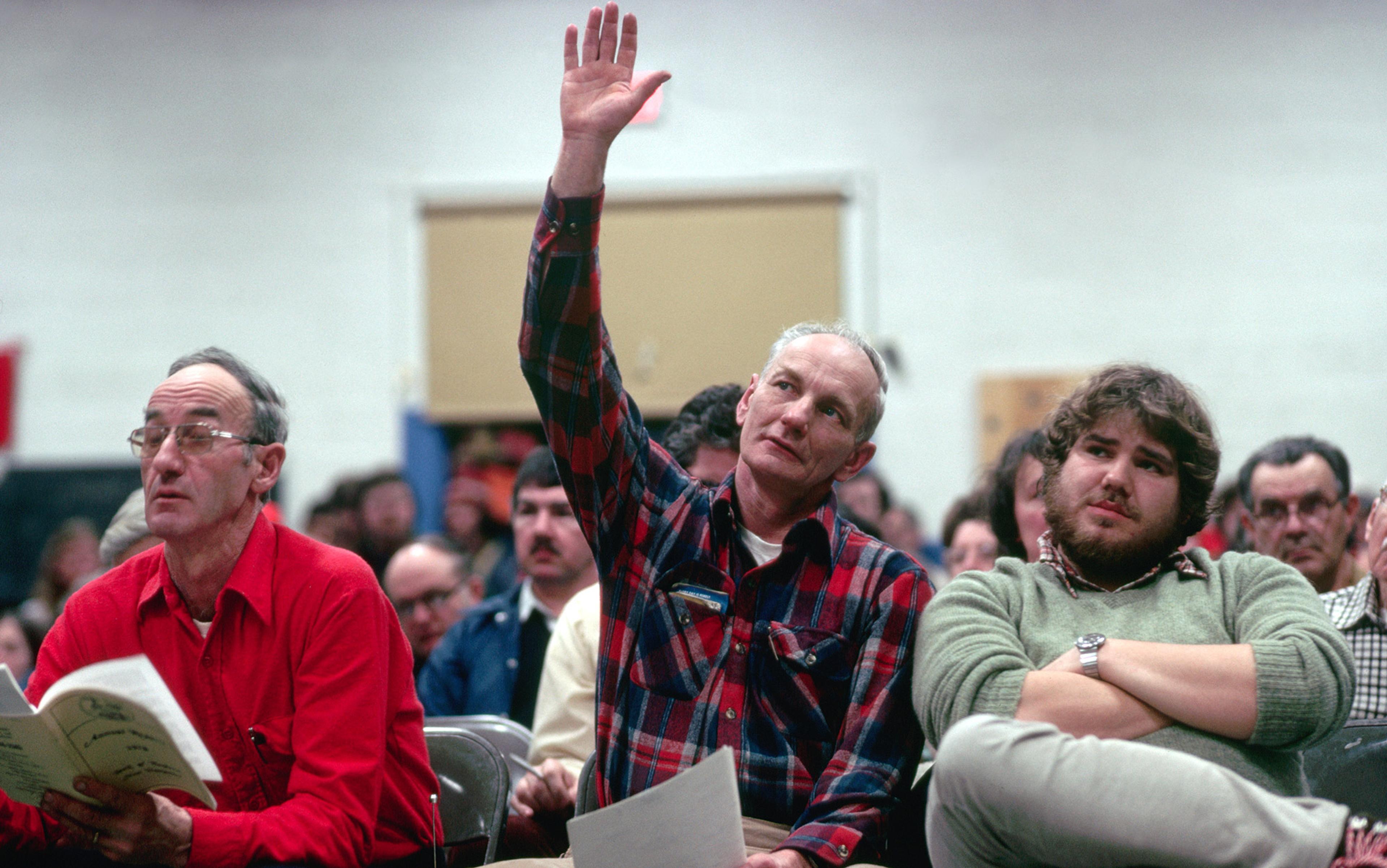

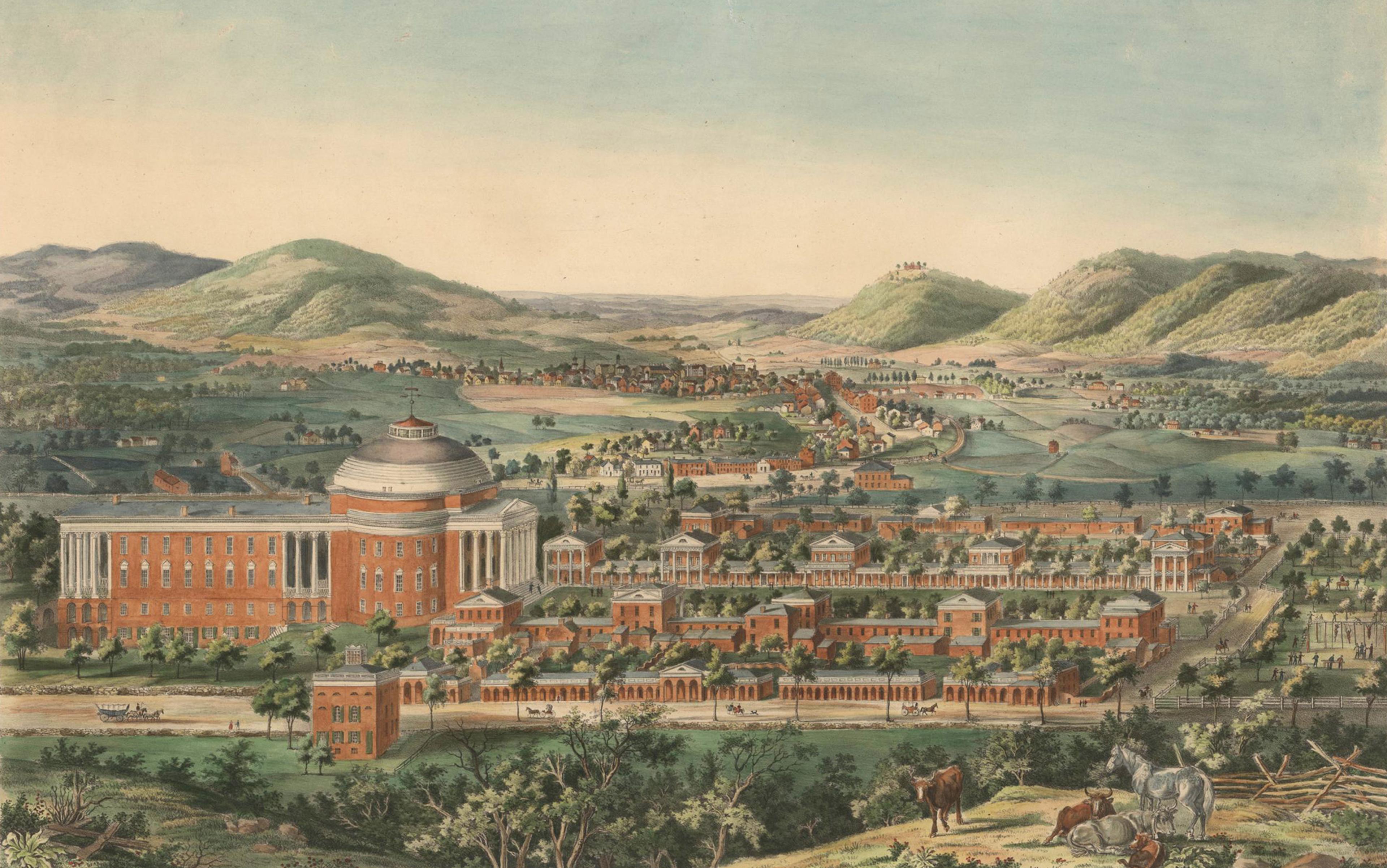

The education reform movement has been successful, however, because many Democrats are also enthusiastic participants. In 1989, Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, organised the education summit at the University of Virginia that began the process of formulating national education standards. The senator Ted Kennedy encouraged Democratic members of Congress to vote for No Child Left Behind. In 2009, the Barack Obama administration ran the Race to the Top competitive grant programme that incentivised states to adopt the Common Core standards in mathematics and English. The presidential candidate Hillary Clinton supports the Common Core and many other planks of education reform, as does her likely Secretary of Education Linda Darling-Hammond. Today, few Democrats with a national profile speak up for Dewey’s ideal of progressive education.

Why does this matter? Progressive education teaches children to pursue their own interests and exercise their voice in their community. In the 20th century, these kinds of young people participated in the movements against the Vietnam War and for civil rights. They founded Greenpeace and Students for a Democratic Society, listened to the Beatles and attended Woodstock, and established artistic communities and organic groceries. Though Dewey was not a beatnik, a hippy or a countercultural figure himself, his philosophy of education encourages young people to fight for a world where everyone has the freedom and the means to express their own personality. The education reform movement is not just about making kids take standardised tests; it is about crushing a rebellious spirit that often gives economic and political elites a headache.

For those who think that democracy ought to be a way of life rather than merely a means to select leaders, and that schools serve a vital civic function of teaching children to become autonomous adults, now is the time to recover the vision Dewey outlined in Democracy and Education. The book presents an inspiring vision of children learning to express their individuality in ways that enrich the community. Dewey teaches us that children learn about democracy by watching educators and citizens make important decisions within their schools, rather than by following orders from above. He also shows us how education progressives can sometimes win even if, as is the case now, reformers have the ear of the wealthy and powerful.

Born in 1859 in Burlington, Vermont, Dewey earned his doctorate at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore before beginning an academic career primarily at two institutions: the University of Chicago and Columbia University in New York. At the beginning of his career, Dewey grappled with the problem of how to reconcile absolute idealism and philosophical naturalism. On the one hand, he shared Hegel’s aspiration to overcome the divisions that separate the individual from the community, the brain from the hand, and the head from the heart. On the other, he thought that Charles Darwin’s work prompted philosophers to rethink fundamental presuppositions, including whether reason is a pure faculty or rather a way to describe human intelligence imperfectly navigating the material world. Dewey’s work in the early part of his career was dedicated to thinking through this challenge in order to arrive at a doctrine variously called instrumentalism, functionalism or pragmatism.

In 1894, however, Dewey faced a dilemma that gave a new purpose to his philosophical career: choosing a school for his children. In a letter to his wife Alice, Dewey wrote: ‘When you think of the thousands and thousands of young ones who are practically ruined negatively if not positively in the Chicago schools every year, it is enough to make you go out and howl on the street corners like the Salvation Army.’ Shortly thereafter, Dewey helped to open the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago where Alice subsequently worked as a teacher and principal, and four of his own children attended. In recent years, Obama, the then-senator, as well as the mayor of Chicago Rahm Emanuel and the former secretary of education Arne Duncan have sent their children to the Lab School.

For Dewey, however, it was not enough to ensure that his own children received a good education. He maintained that the future of US democracy hinged on offering a well-rounded, personalised education to all children and not just those of the wealthy, intelligent or well-connected. Dewey’s pedagogic creed is that ‘education is the fundamental method of social progress and reform’. Schools could teach students and communities to exercise autonomy and make democracy a concrete reality. The very name of the Laboratory School suggests that Dewey wanted the ideas developed there to be disseminated among education researchers and policymakers. What was unacceptable was a two-tiered education system that reinforced class and racial divisions.

Dewey’s vision brought him into conflict with industrialists and administrators who thought that schools should primarily prepare the vast majority of the population for the workforce. In 1915, Dewey had a public exchange in the pages of The New Republic with David Snedden, the commissioner of education for Massachusetts. Snedden argued that public schools should train children for the types of jobs that they would be likely to do once they graduated. Dewey responded that vocational education should not ‘adapt’ workers to the economy but rather teach kids how things work so that they could lay the ground for an industrial democracy. The Smith-Hughes Act (1917) and the Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education (1918) enacted laws and policies that seem to support Snedden’s vision of vocational education for the masses.

Dewey and the progressive movement, however, won a crucial concession from the vocational education movement. Snedden wanted separate schools for the college-bound and for those destined to work on farms or in factories. What transpired, instead, was that public schools added woodworking shops and garages to teach automotive technology and the like. This compromise partially realised Dewey’s vision. Philosophically, Dewey sought to overcome the dualism between the mind and the body and, pedagogically, he sought to bring the liberal arts and vocational education into closer contact. Though Dewey opposed efforts to track kids from an early age, he wanted schools to be places where kids from different backgrounds and with diverse interests could meet and talk with one another.

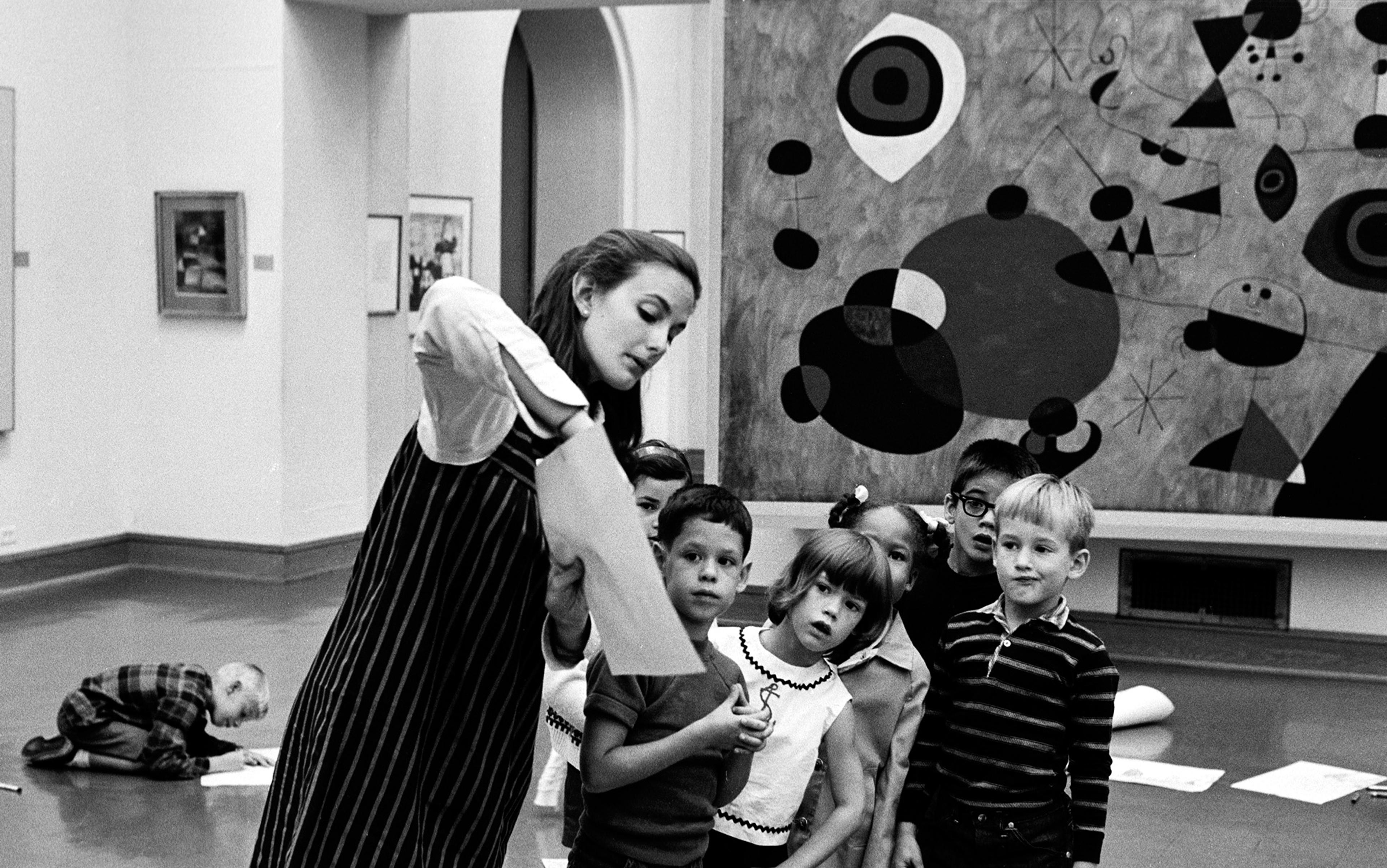

Dewey’s philosophy exercised a profound impact on US education in the mid-20th century. One reason is that many powerful individuals and groups advocated his ideas, including at Teachers College, Columbia University, as well as at the Progressive Education Association, at the US Office of Education and at state departments of education. Dewey’s influence peaked during the ‘Great Compression’, the decades after the Second World War when the middle class had the clout to say that what is good for wealthy people’s kids is what is good for their own. In Democracy and Education, Dewey envisioned schools ‘equipped with laboratories, shops and gardens, where dramatisations, plays and games are freely used’. If a public school has a gymnasium, an art studio, a garden, a playground or a library, then one can see Dewey’s handiwork.

In 1985, a few scholars wrote a book called The Shopping Mall High School to deride the tendency in the US to offer a wide array of courses, many of which have a tenuous connection to academic subjects. For Dewey, however, the other side of this story is that schools and communities were trying to find ways to engage children. As we shall see, Dewey did not think that schools should simply pander to children’s current interests. At the same time, he opposed efforts to impose a ready-made curriculum on children across the country – or, more pointedly, on those whose parents could not afford to send them to private schools.

Dewey wrote Democracy and Education based upon his lectures at Teachers College. The book is, technically, a textbook, and it contains useful advice for teachers and administrators. He also said that the book ‘was for many years that in which my philosophy, such as it was, was most fully expounded’. Dewey’s philosophy lays the foundation for his pedagogy and ensures that his book is still worth reading a century after publication, yet his philosophical style also puts a barrier between many readers and the actionable ideas. We might lower that barrier by exploring the meaning and significance of one of the key themes of Democracy and Education, namely, that school should be interesting for children.

Schools ought to be the site where we model society and allow each child to add her own distinct voice to society’s choir

According to Dewey, all children enter the classroom with interests. ‘To take an interest is to be on the alert, to care about, to be attentive.’ Children care about their family, their neighbourhood, and their own lives. They also can become interested in new things under the right circumstances. Dewey’s concept of interest has analogies to Hegel’s concept of Geist (spirit) as both are at the core of one’s being, and expressive of a larger entity. But one does not need to be a scholar of German idealism to grasp Dewey’s point that different children become ‘alive’ when doing some things and not others.

The task of the teacher, according to Dewey, is to harness the child’s interest to the educational process. ‘The problem of instruction is thus that of finding material which will engage a person in specific activities having an aim or purpose of moment or interest to him.’ Teachers can employ Dewey’s insight by having a pet rabbit in the classroom. As students take care of the animal, and watch it hop about the classroom, they become interested in a host of topics: how to feed animals, the proper care of animals, the occupation of veterinarians, and biology. Rather than teach material in an abstract manner to young children, a wise teacher brings the curriculum into ‘close quarters with the pupil’s mind’.

According to Dewey, teachers should cultivate a student’s natural interest in the flourishing of others. It is a mistake to interpret interest as self-interest. Our thriving is intimately connected with the flourishing of other people. The role of democratic education is to help children see their own fate as entwined with that of the community’s, to see that life becomes richer if we live among others pursuing their own interests. Democracy means ‘equitably distributed interests’. All children – rich, poor, black, white, male, female, and so forth – should have the opportunity to discover and cultivate their interests. Schools ought to be the site where we model a society that reconciles individualism and socialism, and that allows each child to add her own distinct voice to society’s choir.

What is controversial about Dewey’s concept of interest? Sometimes, far-right groups share the following quote attributed to Dewey: ‘Children who know how to think for themselves spoil the harmony of the collective society, which is coming, where everyone is interdependent.’ There is no factual basis for this attribution, and for good reason: it contravenes Dewey’s ambition to achieve a higher synthesis between strong-willed individuals and a democratic society, not to crush a child’s individuality for the sake of social uniformity. Dewey makes this point crystal clear in his essay ‘The School and Society’ (1899), where he announces a Copernican revolution in education whereby ‘the child becomes the sun about which the appliances of education revolve’.

Here, then, we understand the explosive core of Dewey’s philosophy of education. He wants to empower children to think for themselves and cooperate with each other. The purpose of widely distributing interests is to break down ‘barriers of class, race, and national territory’ and ‘secure to all the wards of the nation equality of equipment for their future careers’. Imagine a world without racism or sexism, one where all children get the same kind of education as the wisest and wealthiest parents demand for their own children, and one that trains workers to question whether their interests are being served by the current ownership and use of the means of production. Dewey is the spiritual head of the New Left whose writings have both inspired teachers and infused schools, and provoked a reaction from those who detest this political vision.

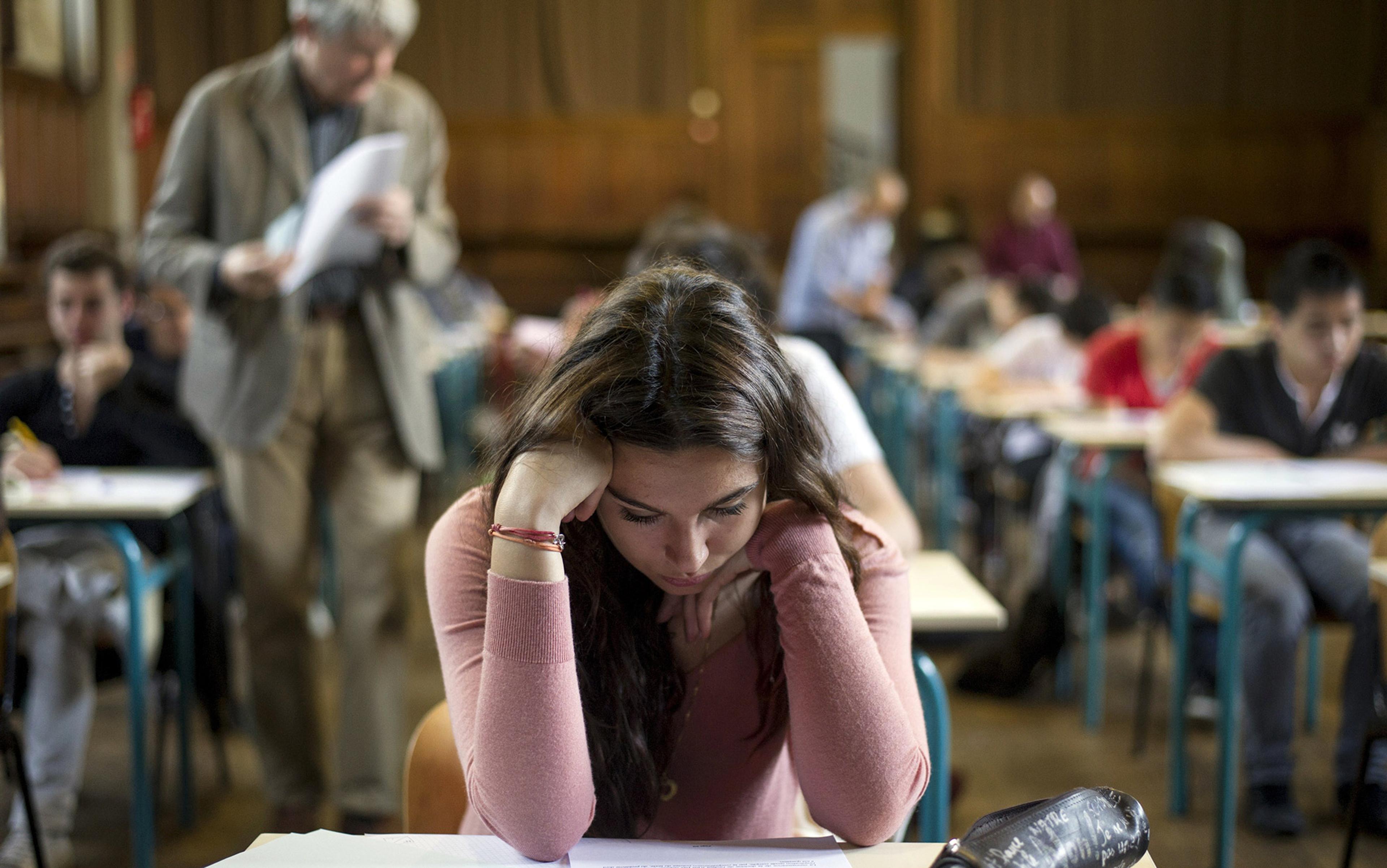

A perennial critique of Dewey’s philosophy of education is that it does not adequately introduce children to Western civilisation or the rigours of scientific thinking. In ‘The Crisis in Education’ (1954), the German philosopher Hannah Arendt decries ‘the bankruptcy of progressive education’. Though she cannot bring herself to mention Dewey by name, she suggests that his ideas ‘completely overthrew, as though from one day to the next, all traditions and all the established methods of teaching and learning’. Decades later, the American educator E D Hirsch, Jr argues in Cultural Literacy (1987) that Dewey is a Rousseauian Romantic who thinks that children can be trusted to teach themselves everything they need to know. However, according to Hirsch, ‘Tarzan is a pure fantasy’, and what children need to do is learn key ideas and facts about our culture – which, conveniently, he includes in an appendix to his book. More recently, the Common Core claims to cure the problem that the US curriculum has tended to be a ‘mile wide and an inch deep’.

All of these assaults on Dewey misrepresent his philosophy. Dewey always retained Hegel’s ethical ideal of reconciling opposites to achieve a higher synthesis. In his essay ‘The Child and the Curriculum’ (1902), he explains why it is essential to keep both things in mind when designing and running the schools.

Dewey believes that educators need to place themselves in the mind of the child, so to speak, to determine how to begin their education journeys. ‘An end which is the child’s own carries him on to possess the means of its accomplishment.’ Many parents who take their families to children’s museums are acting upon this idea. A good museum will teach children for hours without them ever becoming conscious of learning as such. Climbing through a maze gives children opportunities to solve problems; floating vessels down an indoor stream teaches children about water and hydrodynamics; building a structure with bricks and then placing it on a rumbling platform introduces children to architecture: all of these activities make learning a joy.

For Dewey, however, it is essential that educators lead children on a considered path to the cutting-edge of scientific knowledge on a multitude of topics. A good teacher will place stimuli in front of children that will spark their imagination and inspire them to solve the problem at hand. The goal is to incrementally increase the challenges so that students enter what the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the 1920s called ‘the zone of proximal development’ where they stretch their mental faculties. At a certain point, children graduate from museums and enter a more structured curriculum. There can be intermediary or supplementary steps – say, when they make a business plan, learn to sail, or intern at an architect’s office. Eventually, teachers have to rely on traditional methods of reading, lecturing and testing to make sure that students learn the material.

In the conclusion to ‘The Child and the Curriculum’, Dewey enjoins: ‘Let the child’s nature fulfil its own destiny, revealed to you in whatever of science and art and industry the world now holds as its own.’ He has faith that the child’s nature will find expression in the highest forms of human endeavour and that, for example, a kindergarten artist might grow into an accomplished painter. Dewey also believes that individual expression tends to lead to socially beneficial activities. These articles of faith are not necessarily vindicated by experience. Sometimes children choose the wrong path, and sometimes well-educated individuals seek to profit from other people’s misery.

‘What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all of its children. Any other ideal for our schools is narrow and unlovely’

For Dewey, however, democracy requires running the risk that all children, and not just those of the wealthy or connected, deserve a well-rounded education. Dewey wants schools to teach children to think for themselves and act in ways that benefit the community. He envisions a society where each person can express himself or herself in a manner that enriches everyone – in the way that an orchestra harnesses the gifts of its members or a potluck becomes more fun when many people bring their signature dish. Dewey’s vision inspired generations of teachers and parents and, for a few decades, shaped education policy. It would be a tragedy for the schools, and our democracy, if we gave it up for the paltry vision of an education model based on standardised tests.

Looking around the contemporary political landscape, it is easy to become despondent about the prospects of progressive education. Economic and political elites agree on the main elements of so-called education reform. Parents and teachers have been fighting back, but they don’t have nearly the same political connections or economic might.

Dewey, however, also provides guidance for how progressives can win victories in education policy. Americans still believe in the ideal of democracy. No matter how much power education reformers get at the top of the political order, they still need support from the population for the reforms to stick. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for instance, has spent millions of dollars trying to prop up support for the Common Core even as public opinions show widespread disillusionment with the standards. Despite their money and power, education reformers are scared by the parent-led movement to refuse the Common Core standardised tests. They should be.

Dewey shows us that appeals to democracy carry weight. We recoil at the notion that some children deserve a better education than others because of their parents’ political or economic status. Nobody will say with a straight face that wealthy children should be raised to lead, while middle- or lower-class children are raised to follow, or that the kind of education available at the finest private schools in the US should be an exclusive privilege of those born with silver spoons in their mouths. ‘What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all of its children. Any other ideal for our schools is narrow and unlovely; acted upon, it destroys our democracy.’ Dewey’s words ring as true today as they did a century ago. In the face of the unrelenting attack of the education reform movement, we must fight to actualise Dewey’s vision of great schools providing the foundation for a living democracy.