Do you ever stop to imagine what your great grandchildren will consider to be the defining cultural output of the early 21st century? It is unlikely to be to what we might think. One hundred years ago, in 1913, Schoenberg caused a near riot in Vienna; Marcel Duchamp stuck a bicycle wheel on a plinth; cubism landed, like an alien life form, in New York; and in Paris, Nijinsky and Stravinsky premiered the ballet The Rite of Spring (which Le Figaro called ‘a laborious and puerile barbarity’). It seems a pretty sensational year, to us today, reflecting an extraordinary and tumultuous time.

Yet we are living in a similarly transformational era, fuelled by the rise and rise of digital technology. While it is almost inconceivable that computers do not play a role in your daily life, on stage, in galleries, in literature, the computers lurk at the edges: digital is a tool rather than a medium. I’d like to suggest what might happen when digital becomes the form as well. When an exhibition unfolds around you, wherever you are, or a performance uses the huge quantities of data we generate to choreograph dancers; when dramatists allow their plays to seep off the stage into online social platforms, or poets perform inside video games.

These will be the artists, the works and the commentators to watch. You might not ‘get’ them, but to your great grandchild they will be Duchamp.

We’ve some way to go yet. We use our phones, tablets and computers as a place to catch up with reviews and trailers, and as somewhere we buy tickets, or find parking. We understand that we can interact with creators, actors and stars. We can like them, friend them, follow them, speak to them, or just watch them. So far, though, the contents of mainstream ‘culture’ – the art, design, music and film that are the usual stock in trade of the Barbican Centre in London, the Lincoln Center in New York, or the Sydney Opera House – are remarkably unaffected by the digital revolution taking place in our daily lives.

This might be (ironically) one of Western culture’s slowest and more ponderous epoch shifts. Why are we still – still! – talking about ‘digital art’ (and boxing it up in inverted commas) at all? We don’t talk about photographic art, or amplified theatre. Walk into any major gallery, music hall, theatre or bookshop and you’ll find the conventions of popular culture being transmitted the same way they have been transmitted for the past 100 years. Even at the very cutting edge of theatre or art, you won’t find shows that take willing audience members, dissect their online profiles and create one-off bespoke monologues. Or that transpose data from their subjects – as a wild example, let’s say the sleep data of New York, Basingstoke and a village in Nairobi – into a series of living, eternally updating portraits of those cities. Physical artefacts and analogue culture remain dominant in cultural circles. Unless you count special ‘digital media’ courses – lost between art and architecture in the labyrinthine confusions of academic school structures – student degree shows of 2014 will, mostly, look backwards.

None of this detracts from the value of the artefact. The physical chemistry of actuality has significant primacy over the non-physical. Old is frequently better than new. Books, theatre, pens – a stage with a 600-year tradition – are better storytellers than social media. However, the more time I spend with digital technology, the more I understand it as something best consumed by humans in completely natural ways, through speech and gesture, reflected light, and organic, physical surfaces. In other words, all these smartphones and tablets are just a temporary phase on the way to more natural formats – things we already have and love, like talking instead of typing, or using paper, glasses, watches, tables. The way we ‘digitise’ our lives is unlikely to turn back – but our interfaces (how we interact with that digital information) might well ultimately mimic nature.

I am part of Google’s Creative Lab in Sydney, and I work with cultural organisations and practitioners to help artists, writers and performers look at new ways of using the web, and other digital tools, to make art. We want to enable work that can transport us to new realities in ways that simply were not possible before the binary revolution: before we were able to encode and organise data.

The effort begins by acknowledging that digital culture cannot simply be a label for culture made on a computer – everything is made on a computer – and that digital isn’t a medium. It is not video, or audio, or words that could have existed on videotape or in a book; and it isn’t a distribution channel such as YouTube or Tumblr. Digital is data-led and algorithmic (with potential for every output to be unique). Digital is generative (it builds upon itself and draws on its own process to create new expressions). Digital is contextual (leading, for example, to theatre that builds around you, in a timely and relevant way). And digital is collaborative (using the volume of the world to curate or create together).

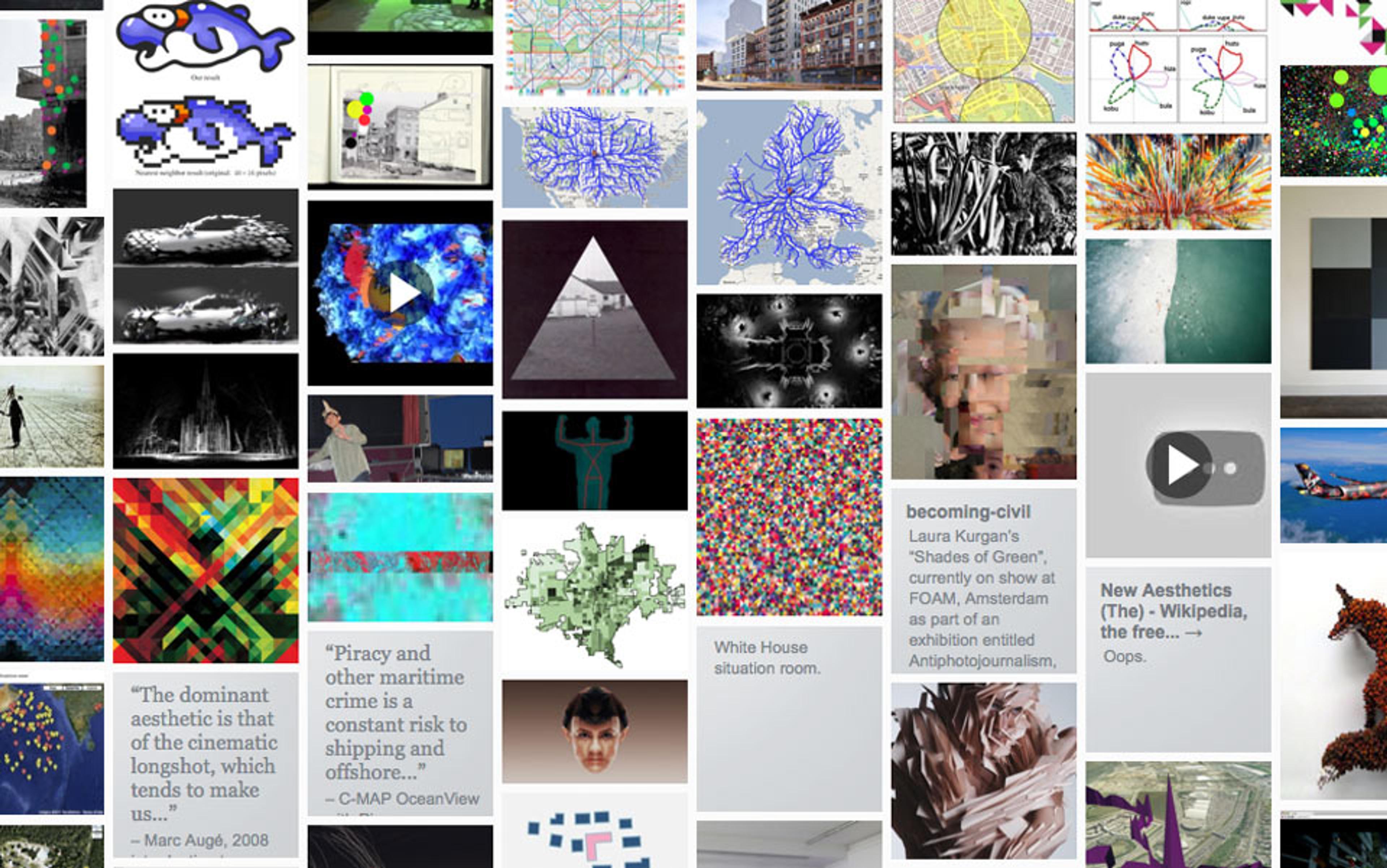

Writing this essay at the end of 2013, I became aware of The Wrong. I hadn’t known about this digital biennale of nearly 500 artists, 30 ‘pavilions’ and a two-month run in 10 cities worldwide until the biennale organiser emailed me. How had I missed it? The answer, I believe, lies in something altogether structural: the growth in creative output that we are experiencing in our daily lives. After all, it probably couldn’t have been possible for 500 artists to exhibit together during the Renaissance without anyone noticing.

It used to be that the passage of time acted as a filter, removing the noise and the superfluity of each generation’s cultural output. But in this era of instant and unlimited information, we’re forced to create our own filter bubbles to do the distilling for us, parsing the amount of information in our lives to acceptable levels. Once in your bubble, on your island, or buried in your echo chamber – whichever metaphor you choose – you can be almost entirely oblivious to the world around you. There is no ambient noise except by choice, little room for coincidence, and for the uninquisitive this makes for a very narrow, algorithmically comfortable existence.

Hearing about The Wrong made me realise that I could not write this article without acknowledging that I write from my own bubble. It is not just other writers that I might not have read, but entire festivals of digital art I might have missed, entire catalogues of digital theatre, entire Eisteddfods of digital literature, music and performance. I am filtered. You are filtered. So from that perspective – let us continue.

Let’s continue with the imperative: the reason for my feeling frustrated that ‘digital art’ is still placed within those inverted commas. In my more idealistic moments, I’d argue that artists must hold a mirror to society, and that it stands to reason that they should use the contemporary tools of that society to create an accurate mirror. I’d also argue for teleportation. Most art forms seek to take you away from where you are and to stimulate a response that is not rational to the fact that you are in a theatre or a gallery, or between the covers of a book; in other words, they create a virtual reality in which you experience an aspect of your society. The dramatic suspense of the theatre transports you to fairy glades with Titania and Bottom’s ‘Ousel Cock’ song. In a West End art gallery, you are sublimely submerged into a white room that removes all sensory distraction. At the Sydney Opera House, you and the audience are of one anthemic voice with Florence and the Machine. You are transported.

But for culture to create a seamless kind of virtual reality, it’s vitally important not to get caught up in the tools we use to create that state of mind. We should rather focus on the effect. Art is what you do to the viewer, not how you did it. Books, paintings, theatre, dance – all of these cause the brain to complete the altered state, comfortably bringing you to a place where you have, in your mind, created a magical reality of your own. You might say that, in this sense, art and culture are just mental exercises, training us in advanced pattern recognition and creating psychological reward structures. It is hard work for high reward.

any work can be created, distributed, consumed, copied and compromised, then collapse under its globally parodied self-referential state in a matter of days

And yet we are moving from a reality where information is static – held in time and place in books, on stage, or in images – towards a world where information is entirely fluid and anyone can know everything about anything, anywhere. We understand this in our daily lives, but it creates huge scope for artists to explore various potentials of the form – some exciting, others troubling – that are as crucial in describing our world today as cubism was 100 years ago. The tools of distribution are ubiquitous, as are the tools of production; our ability to pause for discernment and consideration is decreasing; and appropriation is instantaneous as memes evolve, explode and die in days and weeks. In other words, any work can be created, distributed, consumed, copied and compromised, before it collapses under its own globally parodied self-referential state in a matter of days.

It is extraordinarily challenging to reconfigure this sometimes incomprehensible technology to make art in a way that doesn’t focus on the medium itself. It’s a challenge for art schools to see the creative plasticity inherent in the new tools. It is physically challenging for galleries and theatres to show, hard to explain, and really, really hard to sell. In fact, since the format makes it so difficult to create unique artefacts, there is, often, nothing to sell. While you might be able to create your improv music, performance work or video art with no budget, that is simply not possible when the work requires production budgets in the tens of thousands (the industrial-scale landscapes made by electronic artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, for example), or whole teams of developers and producers (such as those we at Google brought into the Royal Shakespeare Company for a one-off digital production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream last June).

This kind of art isn’t supported institutionally because there is no provenance, no legacy, and the institutions with the capacity to preserve art, music or literature with digital at the core see themselves as bastions, not keepers of culture. Nor is it profitable, because we need new models of commerce for these art forms; the classic models – either grant-maintained culture, or the mysterious art market – calculate (and inflate) the value of scarce resources, but this doesn’t translate into work that defies scarcity or physical possession. And as hardware manufacturers upgrade their operating systems, digital work is simply being lost. It is a truly ephemeral period. It’s very hard to make sense of, and enormously hard to see where it’s all going.

But that is precisely the task we set our artists. And it’s what sets artists apart: they look forward. Those artists who become well-known among future generations have always utilised contemporary technology; people such as the sculpture-maker Ryan Trecartin and the video-art pioneer Nam June Paik; or the light artists Dan Flavin and James Turrell, photographer William Eggleston; or even, for that matter, Man Ray, Duchamp and Shakespeare; Leonardo da Vinci, Johannes Gutenburg and Paolo Uccello. Contemporary art and culture explore tools and paradigms that are designed to make sense to a future audience, not the current one. Given that, are we comfortable that today’s ‘art’ is still using 19th-century technology? Do we feel as discomfited and electric today as did the contemporary audiences for James Joyce, or Pina Bausch?

I fear we’re missing out, and that’s a shame. Speaking as an artist for a moment, rather than a technologist, I can’t help but be enormously excited by the canvas that today’s artists have to create this electricity. Their art, the art of the future, will be time- and location-specific, even as it’s built on personal, historical and geographic data that can shift and morph to adapt the experience to wherever you might experience it. At the same time, physical surfaces are likely to become more receptive to digital information, both visually and at a sensory level, so we can expect the physical world around us to become more malleable and transitional, depending on us.

I suspect, too, that we will see a huge rise in authenticated art; that is, cultural experiences related to our physical proximity and personal history within a particular artwork or experience. And whether that happens within the physical boundaries of a ‘gallery’ or simply out in the real world, art might well come shopping with us.

There will be a comprehensive split between work that is artist-led, purely passive and experienced as a broadcast experience, and the idea of engaged culture. As a participant, or as a viewer, you’ll either actively engage within a cultural work or not – from the ‘He’s behind you!’ leitmotif in the immersive theatre works of a company such as Punchdrunk, to the playful sensory atmospherics in the installations of an artist such as Ólafur Elíasson. There will be a growing dichotomy between passive and engaged consumption of culture.

If all of this sounds horribly uncomfortable – good! Because here’s the hard truth: paintings are not going to cut the mustard. Today’s society has complexities that artists will reflect back to us through the way we’ll remember experiencing them: multi-linear, time-agnostic, fragmented and discordant – like the insane, eccentric world of Yung Jake, who makes rap videos out of such clichés of digital culture as Facebook likes and YouTube viewcounts.

This July, the Barbican Centre in London will open its doors to Digital Revolution: An Immersive Exhibition of Art, Design, Film, Music and Video Games. Intended as a survey of the digital arts since the 1970s, the exhibition will include immersive and interactive installations, games culture and, in a collaboration with Google, DevArt (which explores the possibilities of coding as a creative art form). In a world lacking a neat avant-garde creating ‘next generation’ cultural output, the show ought to provoke questions about why it is taking so long for ‘digital’ to reach the heart of culture. Ideally, I’d like it to ask who the next generation of cultural practitioners are, who their audience is, and why they make their work. I’d like it to ask: when might digital ‘art’ just be art? And I’d like it to showcase Ryoji Ikeda, Jon Rafman, Yung Jake, John Gerrard, James Bridle, or Dries Verhoeven – all international artists producing work with digital at its core.

On our journey from a world of static information to the fluid world we’re building, we are still only a small way along. The Barbican show is just the first chapter. The truth of the matter is that, setting aside the slow pace of change, the challenge of filter bubbles, and the complexity of the medium, we’re still at a familiar place in an oh-so-conventional cultural cycle, which pits those who dismiss contemporary tools and technology as having no place in art, against apologists like me who decry their lack of recognition. And while we appreciate the artistic foresight of the past, we rarely appreciate the artistic foresight of the present, because it feels ugly and difficult. But it has always been so, from Kandinsky to Kafka, since the shock of the new is about patterns not yet recognised, patterns not yet subsumed into the zeitgeist.

The real artists of today will not find favour with us, or with our institutions, maybe not even in their own lifetime, because their work is not for us. It is for our great grandchildren. That said, I will still be happy when no one talks about ‘digital art’ or ‘digital culture’. For, when today’s intimidating technology seems as natural as a pen or a camera, we’ll know we’re on our way to finding our own Stravinskys and Duchamps, and that the cycle is repeating itself.