In October 1958, Pan American Airways began its first regular jet service across the Atlantic. Compared with other forms of travel, flying was already fast. In 1946, it took around 20 hours to fly from New York to Paris, as opposed to the four-and-a-half days to cross the Atlantic by ocean liner. But Pan Am’s new jet-powered Boeing 707, moving at an unprecedented speed of 500 to 600 miles per hour, cut transatlantic travel time to a mere seven hours (about the length it remains today).

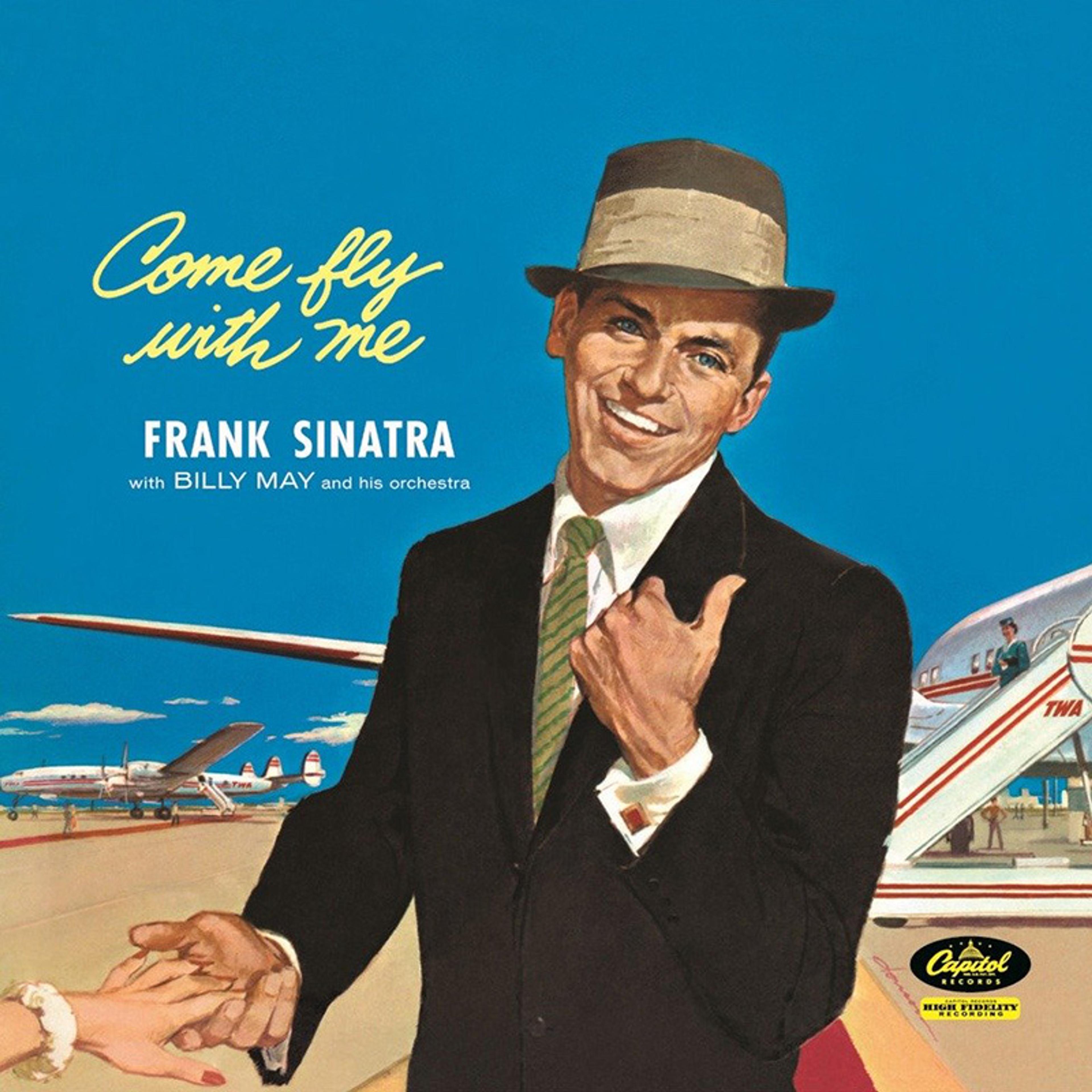

The jet’s incredible speed seemed to some to embody the historical moment. As one author put it in 1959: ‘Every aspect of our time is marked by movement … the aircraft is the most eloquent symbol of this transformation.’ In January 1958, Frank Sinatra’s album Come Fly with Me was released, with a cover that prompted the silver-tongued singer to complain (understandably) that it looked like a poster advertisement for Trans World Airlines (TWA). The album featured travel-themed songs and lyrics referencing a host of far-flung places (Hawaii, Paris and Capri), while never mentioning how fast you could get there. Instead, the title song promised the lovers would ‘float down to Peru’ and ‘just glide, starry-eyed’. Come Fly with Me emphasised the quality of the jet’s movement: barely perceptible, natural and easy. It would be a fitting anthem for an era – roughly the mid-1950s to the end of the 1960s – that’s come to be known as the jet age.

Come Fly With Me (1958). Photo supplied by the author and courtesy Capitol Records.

The jet also increased load capacity, lowering prices and expanding the market for flight. Its speed appealed in particular to businessmen and tourists, who valued saving travel time. This led the burgeoning airline industry and expanding travel business to anticipate that transatlantic flight would quickly overtake ocean passage as the way the majority of travellers would journey between the old and new worlds. They were right. As early as 1958, more people flew across the Atlantic than took the boat. Because this crossing had been such an important site of long-distance travel, the change contributed to the feeling that the jet had made a major social impact, although the era of mass air travel was still a decade away.

What set the jet apart from other planes was not that it flew more quickly (although it did). People willingly hurtled through the air at more than 500 miles an hour in a metal tube not simply to get where they were going faster but also because of the way that the jet rode. In one of Boeing’s best-known ads of the period, a mother and a little boy are depicted flying in the Boeing 707 in domestic comfort – not ensconced in glamorous cutting-edge luxury. Because of the jet’s motion – described as serene and ‘free from vibration’ in ‘high, weatherless skies’ – the manufacturer promised that passengers would be able to hear a watch tick and see a coin balance on a table. A flower (a metaphor for Mom herself, no doubt) would remain fresh through the entire flight. The ad highlights the quality of the ride rather than the speed of the jet. This was a new kind of experience: going far, fast, while seeming to go nowhere at all.

Boeing advertisement from 1958. Photo supplied by the author.

In 1954, Newsweek promised passengers that riding in the new planes ‘will seem like slipping through space. No vibrations, no lurches, and no sense of speed.’ Without the piston-operated engine, the ride was quieter and the plane had little of the characteristic vibration associated with air travel. In 1959, the American Airlines brochure, placed at every seat on their jets, assured that:

[T]there is no sensation of speed whatsoever in jet cruising. The flight is smooth beyond anything you have ever experienced. Vibration, the major cause of travel fatigue, is gone. Engine noise is so reduced that you hear only the air flow passing the fuselage. It is a hard thing to describe the cushioned, insulated sense of comfort you will know in jet flight.

Guidebooks such as Fodor’s made similar pledges: ‘You’ll find the jet takes off smoothly and climbs with a feeling of steadiness and certainty that piston engine and even turbo-prop planes don’t have … you’ll be free from the fatiguing elements of vibration and noise.’

Jet planes in fact do make noise on take-off and landing, called the jet whine, which became the basis for later complaints about ‘noise pollution’ in residential areas near airports (and one reason why supersonic jets always had limited routes). But the ride inside the plane and the sense of going nowhere – the sense of sensationlessness – defied the logic of the transport’s speedy quality. As Milton Roberts, a businessman in San Diego, explained: ‘This is just like sitting in an armchair; it’s wonderful. I really had no idea that the 707 tourist section was so comfortable.’ Another passenger, Florence Vita of Los Angeles, went further: ‘This flight is fabulous. I just cannot get over the feeling that we’re standing still. Why, there doesn’t seem to be any motion at all in here!’

The history of transport has often served as a prism through which to view such large structures as trade, state-building and international politics. But as the debut of the jet suggests, transport history can also offer an important way to understand changes in subjective experience. The cultural historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch, in his pathbreaking book The Railway Journey (1977), identified the emergence of a new kind of vision that came from looking out of the train window, which he called panoramic vision, noting that as passengers rode they could no longer distinguish between foreground and background.

When we think of how flight changes one’s subjective experience, we often consider it as creating a new kind of ‘view from above’, distinct from those that had previously been derived from such places as mountaintops and towers. Similarly, planes afforded new kinds of surveillance that have aided military operations as much as commercial and scientific ones, which is why they are associated with forms of social control: everything from the uses of aerial bombs to drones suggests just how strategically important gaining the view from above could be. And looking out the window of a low-flying plane has prompted many reflections on new kinds of planetary consciousness, and an awareness of the shape of urban infrastructures.

But passengers saw very little by looking out of the window from the heights at which jets flew for most of their flight’s duration. Although at 30,000 feet one could hypothetically see a horizon that was 142,000 square miles, in reality, there was less to see than ever before. Windows on jets were smaller because of pressurisation, and there were fewer windows per passenger: the Boeing 707 sat four people across, so most passengers were far from the window or from any ‘view from above’. In fact, the 707 offered the first airplane window with shades, and in 1961 TWA and United Airlines began to offer regular inflight entertainment. The view from the jet was turned toward the inside of the plane, rather than towards the world outside its small portholes.

When the French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote about the jet test pilot in his essay ‘The Jet-Man’ (1957), he underscored the lack of sensation experienced by such pilots: ‘the jet-man … is defined by a coenaesthesis of motionlessness (“at 2,000 km per hour, in level flight, no impression of speed at all”)’. The industrial designer George Nelson in 1967 described passenger encapsulation – ‘The prime characteristic of modern travel is that it tends to isolate one from experience’ – and also saw travel as the experience of being transported through a set of interconnected tubes. The faster the vehicle went, the less the passenger experienced any sense of motion at all, thanks to a design that naturalised the jet’s mechanically powered motion, extending, or perhaps one could say finally ‘perfecting’, the relation between human and machine movement so that their differences became increasingly imperceptible. A passenger, interviewed about flying in a jet in 1966, said: ‘The plane is really yourself, it is you, with wings.’ What could be a better definition of the experience of fluid motion? Human and machine had seemingly become one.

Jet-age airports were passthroughs and interchanges, built with their own obsolescence in mind

The jet defined an age not because it gave people a new view from above but because it transformed subjective experience – extending its characteristic ‘nonexperience’ to life on the ground, in the form of a jet-age aesthetic. That aesthetic does not consist of the familiar aspects of air culture such as the decoration of jet interiors, the clothing worn by flight attendants, the meals served on board, the ads created by firms hired to promote the new jet service, or airport art, all of which are more akin to what one would call a design style, though it is significant in the way that the aesthetic conveys symbolic meaning and value.

Defining an age means going beyond fashioning a look or style in and around the jet. Additionally, its significance far exceeds the social, political and economic impact of the jet plane’s speed. While it is true that the jet inaugurated the possibility of mass tourism and contributed to a form of globalisation in which those countries and companies that made jets, built airports and ran airlines asserted new sinews of power in ways that reshaped connections between states and their populations around the world, this is also not the jet’s single greatest legacy. Rather, the greatest legacy is that the jet-age aesthetic transformed subjective experience itself, ushering in a culture that would soon conceive of the ‘networked society’ because human subjects could visualise being connected without being physically present. This is the consequence of the adaptation of the jet’s fluid motion throughout the culture more generally, and at the level of the individual’s senses.

The jet-age aesthetic is on display in the new and redesigned airports built during 1955-1962, such as Paris Orly, Los Angeles International, the TWA Flight Center at John F Kennedy in New York, as well as the main terminal at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, DC. These are often understood as the era’s most enduring symbols through which planners and architects put into practice the jet’s feeling of going nowhere fast, where they had set out to design new kinds of spaces that were seamless and fluid.

These projects were less about the terminal as symbolic architecture (despite how they have often been studied). Instead, planners emphasised the continuity of the passenger’s journey and obsessed over the ease of circulation as the airport’s greatest goal. Rather than build new monumental gateways to replace what train stations had been for the 19th century, jet-age airports were passthroughs and interchanges, built with their own obsolescence in mind. They were antimonumental, ready for their extinction in the face of expansion and the possibility of new technology. When planning for Dulles, the architect Eero Saarinen wrote (more than a year into the project) that he hadn’t even considered the design of the terminal building because his great ambition and focus was the mobile lounge – this he envisioned as a ‘spacious room isolated from fumes and noise’ that would detach and eventually load passengers directly onto the planes waiting in mid-field.

Airports are not the only jet-age spaces to advance the jet-age aesthetic. When Los Angeles International (LAX) reopened after its redesign in 1961, the chairman of the Federal Aviation Administration, Najeeb Halaby, quipped: ‘You will have the first airport terminal area specifically designed for the jet age and it may well achieve some of the world-wide renown, some of the international acclaim as – who knows – Disneyland.’

The team of architects, William Pereira and Charles Luckman, while in the midst of the LAX design, also drew Disneyland’s very first (and rejected) plan at Walt Disney’s invitation. When completed by the group of people who would eventually become known as ‘imagineers’, Disneyland was pure jet-age aesthetic: making the experience of motion itself into something beautiful, pleasurable and easy. Fluid motion became an object to see around the park as trains and boats and planes and rockets narrated the history of transport as the history of progress. Transport vehicles put visitors in a form of constant motion that they were meant to hardly feel. Disneyland has never been a park dedicated to thrills and spills. Instead, like riding in a jet, visitors can glide over London in a smooth and easy path, and the park’s hub and circular design creates the ultimate in flow. Walt Disney and the imagineers of WED Enterprises made the park specifically about people-moving, even naming the crowning achievement of the 1967 redesign of Tomorrowland the WED PeopleMover.

The jet-age aesthetic also altered subjective experience through the image culture of the period (which itself was enhanced through a physical system of circulation powered by the jet). As the media theorist Marshall McLuhan noted in 1964, the photograph created a world of ‘accelerated transience’ and the age was one in which ‘travel differs very little from going to a movie or turning the pages of a magazine’. The notion that the image had come to dominate the age had been evolving over the course of the century – since the advent of reproductive technologies such as lithography and photography – and had taken on new power with the rise of advertising and public relations, on the one hand, and wartime propaganda, on the other. Artists and intellectuals, such as those associated with the Bauhaus, believed that thought itself was visually organised, as had been promoted by Gestalt principles as early as the 1920s.

‘We look into a mirror instead of out a window, and we see only ourselves’

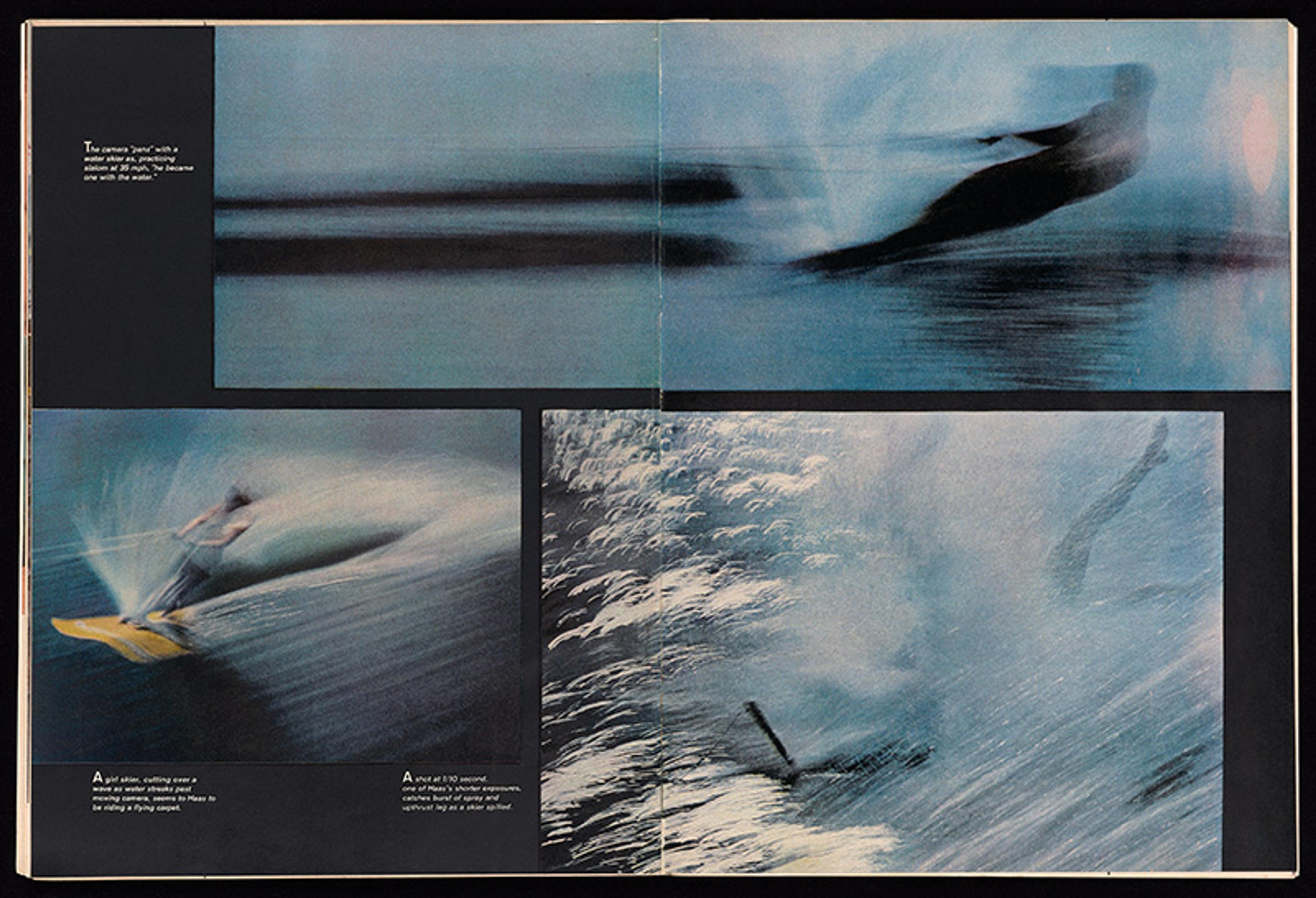

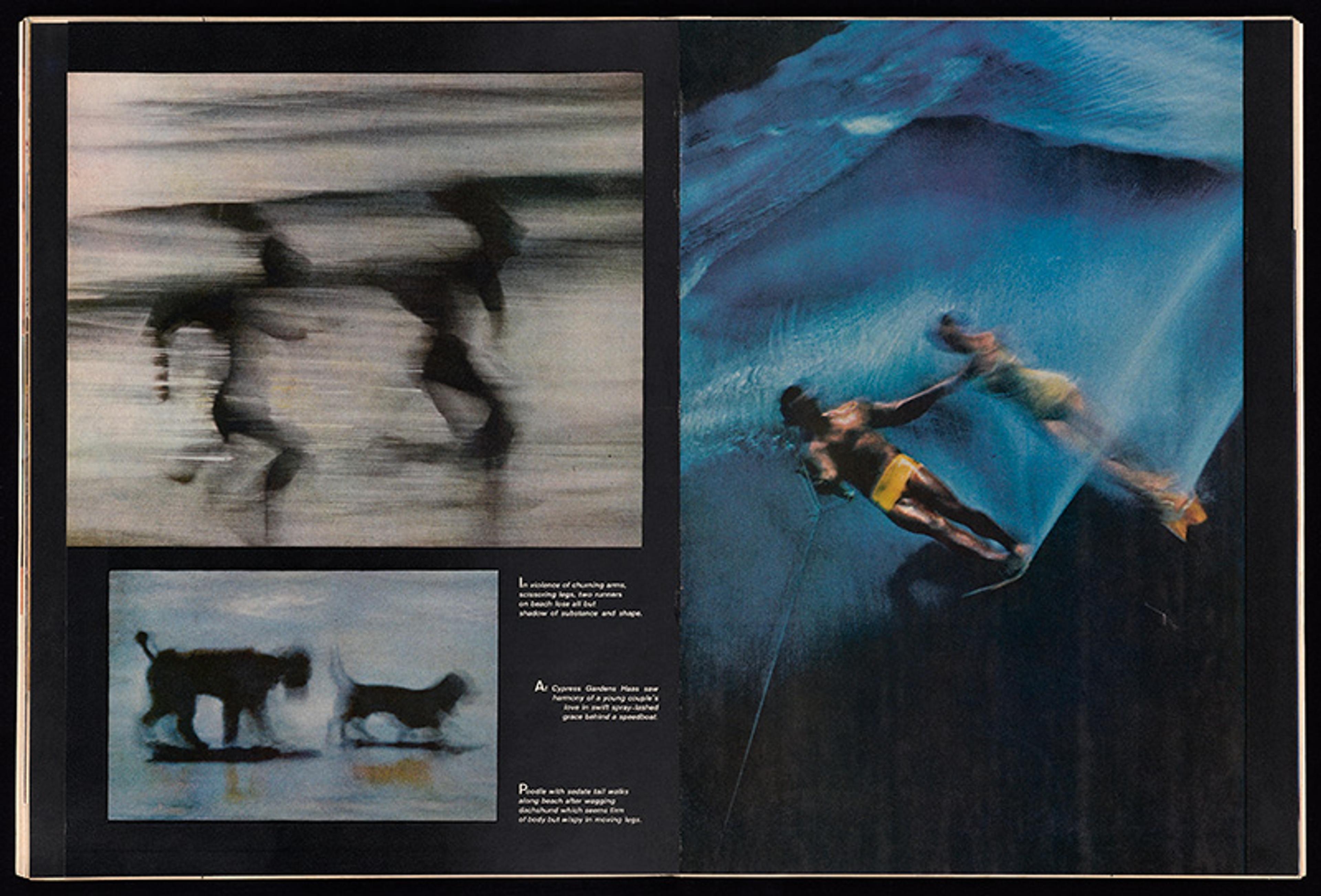

Photographically illustrated newsmagazines, often disparaged by historians as vehicles of outdated consumerism, played an important role in the elaboration of the jet-age aesthetic. They became the primary vehicle of what in 1952 Wilson Hicks, Life’s picture editor and eventual executive editor, called ‘The Age of the Visual Image’. Pioneers in photojournalism, such as the photographer Ernst Haas, brought the jet-age aesthetic to the pages of Life magazine. Haas used colour and blurring to share with readers the tension ‘between the staccato movement of living creatures and the fluid progress of machines’. Even arcane activities such as bullfights became opportunities for the photographer to manipulate the camera eye, perfecting as he did his ‘panning’ of the still camera to effect the blur in order to achieve what he called ‘the perfect flow of motion’.

From ‘The Magic of Color in Motion’ Life Magazine, August 11, 1958. Photographs by the great Ernst Haas and courtesy the author.

In his book The Image (1962), the historian Daniel Boorstin connected the image to the profound impact of the jet on human subjectivity:

The newest and most popular means of passenger transportation to foreign parts is the most insulating known to man … I had not flown through space but through time.

Boorstin even complained that the nonexperience of jet flight didn’t merely lead to inflight boredom; it also led modern people to lose all sense of history, which he considered a function of understanding how time was located across space. The jet, he concluded, mirrored the functions of media society and shared in its production of pseudoevents and presentist spectacle: ‘We look into a mirror instead of out a window, and we see only ourselves.’ Boorstin, no Luddite, predicted that the jet would lead to a hyperindividuated society of narcissists. He perceptively argued that the jet’s impact was much greater than the way its speed contributed to the creation of mass tourism. He understood the jet to be not only about travelling farther faster but also about a new kind of ride.

Identifying the jet-age aesthetic thus allows us to understand globalisation at the level of subjective experience. Many media theorists such as McLuhan, Georg Simmel and Walter Benjamin have correlated human sensory change to media technologies. The period’s larger media ecology of new spaces such as redesigned airports, Disneyland and the images that circulated in the mass media of magazines, films and television, formed a dense system that produced the jet-age aesthetic and reshaped subjective experience for the global age. The jet plane and these media forms – or, more abstractly, transport and communication – didn’t just lead parallel lives. Together, they participated in creating people who would manage to live in a networked society by easing circulation, not just of people and goods going through space in the form of travel, but as a different kind of subjective experience.

Jet-age people learned to close the distances between physical space and time, and to toggle between the material and immaterial worlds by navigating a combination of newly built spaces and encountering contemporary mass media culture from the late-1950s to the late-1960s. The decade of the jet age itself came to an end, yet no form of regular transport has since outpaced the jet. Simultaneously, the jet-age aesthetic changed us, helping to prepare us for the world we currently inhabit. If seen as a story regarding optimism and excitement in a vision of air travel itself as pure flow, we know the jet age is long gone.

One could see Arthur Hailey’s bestselling novel Airport (1968) and its runaway film version hit of 1970 – whose box office was topped only by Love Story that year – as an indication that the public image of flying had changed remarkably from Sinatra’s invitation to come fly with him. Danger erupts in the skies. The people on this fictional plane include a geriatric stowaway, a psychotic bomb-carrying maniac threatening to kill everyone onboard, and a pilot and stewardess engaged in an extramarital affair. A huge snowstorm has also inhibited the airport team’s ability to clear a runway of a banked plane in order to let the crippled 707 land. Meanwhile, community activists, complaining about the jet whine, had pushed for the closure of the airport’s only other runway. A film like this could use Come Fly with Me only as a sick joke. There was nothing glamorous and fluid about this ride.

People took to the air as never before, and that, in turn, changed how people experienced life on the ground

Public expectations regarding the ease of mobility in the early jet-age years were also dashed by airports that failed to keep up with the demands of people-moving on the ground. The freedom of movement also led to an era of skyjacking. Although the first plane to be taken was in 1961, the period 1967 to 1972 was the heyday of skyjackings, and terror in the sky remains one of the greatest forms of political and social violence used today. The new security-controlled airport is, without doubt, a concrete response to the limits of jet-age visions of fluid motion and experiments in people-moving in real space.

But to focus on airports, or to say that the jet age ‘failed’, or to think only about whether jet travel is still glamorous, misses the larger achievement of the jet-age aesthetic, which was never simply about moving people through airports or flying on jets. The jet-age aesthetic shows that such transport was part of a communications network of spaces – of experiences as well as mediated images. What the jet created was a kind of motion that was glamorised and celebrated: that you could go fast and have a sense of not moving at all. This aesthetic created ‘jet-age people’ who could better mediate between the material and image worlds, saw less antagonism between the human and the technological spheres, and were comfortable rather than distressed at seeing themselves as spectators of their changing world. The jet came to define an ‘age’ in its own time because of its impact on consciousness itself. People took to the air as never before, and that, in turn, permanently changed how people experienced life on the ground.

By the 1960s, ‘the network society’ had begun to emerge as a commonplace concept among sociologists; it has since been incorporated into most fields in the qualitative social sciences and the humanities. The sociologist Manuel Castells, for instance, has identified connectedness – especially that made through mass media and telecommunications – as the basis for contemporary social interaction and organisation. Virtuality stands in for materiality. In short, the network society emerged from the jet-age aesthetic.

It is no surprise that aspects of the jet-age aesthetic keep appearing in 21st-century popular culture: take, for example, the film Catch Me If You Can (2002) or the TV series Mad Men (2007-15), or that the TWA terminal at JFK was repurposed in 2019 as a resplendent hotel designed to bring guests back into the heyday of the jet age. This is not only out of a nostalgia for the sleek look of another time and its good-old-days optimism (now turned quaint, even ironic) that the future was going to be better and brighter. Rather, the presence of such cultural references works to remind us they are anchored in our own present. Today, physical mobility and material barriers haven’t disappeared as those living in the jet age envisioned, but they are now accompanied by even greater ‘immaterialised’ circulation in the flow of images and words via modern media systems that offer to simulate experience and not simply depict it. The internet and its underlying infrastructure offer the most remarkable media form of sensationless, fluid motion. It exemplifies the impact of the jet age, and allows us to make sense of our experiences when ‘surfing’ the internet – when we actually go nowhere at all.