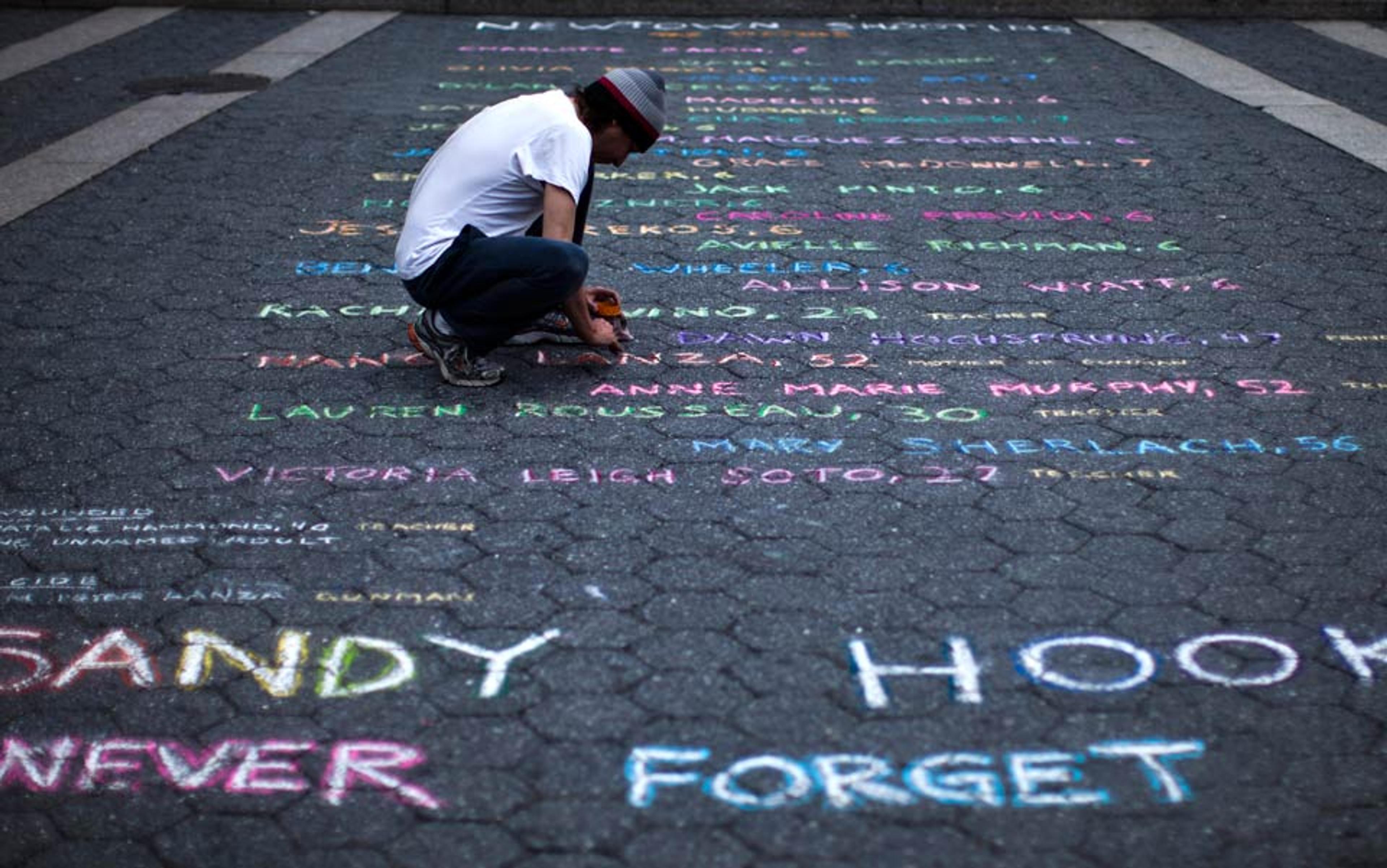

When a troubled young man named Adam Lanza stormed into Sandy Hook Elementary School and slaughtered 20 first-graders and six teachers in a small Connecticut suburb in December of 2012, a shroud of sorrow and confusion engulfed the United States and countries all over the world. Why were all these children murdered, and why did someone so clearly disordered have access to so many guns?

I covered the mass shooting for the New York Daily News, and worked 14-hour days interviewing victims’ families, attending press conferences, and doing as much on-ground reporting as possible. The toughest part of the coverage came a week in, at the memorial for a six-year-old named Dylan Hockley. A slide show, accompanied by a rendition of Leonard Cohen’s classic rock hymn ‘Hallelujah’, with lyrics altered to honour the boy, induced nausea, especially when I thought of all the other children killed and the families they left behind.

Following the mass murder, people in the US began debating their easy access to assault weapons and large capacity magazines. Yet the only change has been for the worse. There have been 74 reported school shootings across the US since Sandy Hook. And there are no signs of this trend stopping. Ease of gun ownership remains a way of life in the US.

But what if there was an alternative to prevent these types of shootings, without eradicating guns? What if predictive policing – something like the ‘pre-crime’ unit envisioned by the sci-fi author Philip K Dick and dramatised in the film Minority Report (2002) – were to intercept killers before they struck? What if authorities could crunch numbers, find patterns and act before homicidal maniacs got the chance?

The effort is already underway. Recently adopted predictive policing methods, in varying stages of development across the US and around the world, have the same goal: authorities hope to anticipate crimes and act before they occur. Initial efforts work largely through computer algorithms, or formulas that analyse years of criminal reports to predict where the next crime will likely transpire.

The New York City police commissioner Bill Bratton is a firm believer in preventive crime fighting. At a recent 21st Century Leadership panel held at the 92nd Street Y community centre in Manhattan, he referenced it as the new norm. ‘The mission of the police is to prevent crime and we are finally at a point in time where we can actually do that with some degree of confidence’, he said in April.

Bratton pioneered a crude version of this concept in 1994, during his first run as commissioner. CompStat, as the system was called, ran statistics and analysed district crime reports, arrest records and other police data to follow crime trends and target criminal hot spots. After patrolling these hot spots for a year, murders had dropped by 60 per cent. By 2003, murders were the lowest they had been since 1964.

Encouraged by that success, the New York Police Department (NYPD) in 2012 partnered with Microsoft to create a predictive policing tool that is far more advanced. The Domain Awareness System retrieves, analyses and instantly displays information from more than 3,000 surveillance cameras, 911 calls, number-plate readers and other sources. The objective is for the department to aggregate and act on the information before illegal activity takes place.

For example, let’s say a suspicious car following children near a school is reported to the police. The predictive system can pull up who owns the vehicle, any arrest records related to the owner, and crimes occurring in the area. It can determine not only where the car is at the moment but, by accessing plate readers around the city, where it’s been in days, weeks and months prior. Based on ‘reasonable suspicion’, all this data may be used to stop a crime when it is still just an idea.

The NYPD unveiled the system in August 2012, and by June 2014 it made its first big hit. After tracking more than 1 million Facebook pages, 40,000 calls from Rikers Island jail and hundreds of hours of video footage from building elevators, hallways and grounds, the police raided a Harlem housing development and arrested 103 alleged gang members. It was the largest gang takedown in New York history. The gangs were accused of two homicides, 19 non-fatal shootings and about 50 other shooting incidents. But the aim of this mass arrest was to prevent a war zone from erupting in the future.

In the quest to predict and prevent crime, New York is hardly alone. In August 2013, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) established a ‘heat list’ with an index of 400 people, thought to be criminals, fanned out across six predominantly black police districts. The CPD said that people on the list included shooting victims who refused to co-operate in prosecuting the shooter, as well as those identified as repeat offenders for violent crimes. The index was collected through an algorithm produced by an engineer at the Illinois Institute of Technology. The method involves officers visiting the homes of individuals they identify as likely perpetrators immediately after crimes occur in their neighbourhoods, theoretically preventing future crimes.

In Los Angeles, the police department now uses PredPol, a predictive policing device that runs years’ worth of crime reports through specialised algorithms to identify locales with a high probability of crime. It places little red boxes on maps of the city to indicate the spots, which are streamed into patrol cars. The police then monitor these 500ft x 500ft areas to stop would-be criminals. PredPol is used in a third of the geographic policing divisions, and focuses on burglary, break-ins and car theft, which together amount to more than half of last year’s estimated 104,000 crimes in Los Angeles, according to reports. In other words, it looks at the location of past crimes to predict future ones.

Dozens of other law enforcement agencies use PredPol. Police in Seattle are using it to zero in on gun violence. Atlanta police use it to forecast robberies. In Pennsylvania, police are focusing on car theft and burglaries. And in the UK, Kent police use it to predict drug crimes and robberies. They all share the common purpose of stomping out crime before it hatches.

In war-prone societies, up to two-thirds of individuals had the warrior gene – versus just one-third in more peaceful nations of the world

But these early predictive systems are only the start. In years to come, many legal experts speculate, brain scans and DNA analysis could help to identify potential criminals at the young age of three. Some evidence for the approach came in 2009 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: researchers from the US and the UK tested 78 male subjects for different forms of the so-called ‘warrior gene’, which codes for the enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), a gene that breaks down crucial neurotransmitters in the brain. One version of MAOA works efficiently; but another version breaks down brain chemicals only sluggishly, and has long been linked to aggression in observational and survey-based studies. Some researchers held that, in war-prone societies, up to two-thirds of individuals had the low-activity gene – versus the more typical percentage of just one-third, found in the more peaceful nations of the world.

To see if this controversial hypothesis held up in the lab, researchers asked the same 78 subjects to take a second test. They were to hurt individuals they believed had stolen money from them by ordering varying amounts of painful hot sauce in their food. (In reality, the ‘thief’ was a computer, so no person was actually hurt.) The findings yielded the first empirical proof that those with the low-activity form of the gene – the warriors among us – did indeed dish out more pain.

These findings soon found their way into criminal court: in 2009, at a trial in Tennessee, the defendant Bradley Waldroup was accused of killing his wife’s friend – by shooting her eight times and slicing her head open – and then slicing his wife again and again with a machete. Yet despite the glaring evidence, he avoided a first-degree murder conviction based in part on the warrior gene defence. He had it.

In the US and Europe, brain scans have in recent years supplemented DNA evidence to indicate criminality. In 2009, for instance, the Italian defendant Stefania Albertani was convicted of murdering her sister by force-feeding her psychotropic drugs and then burning her corpse. Some months later, she tried to kill her parents too. Yet in 2011 a court lowered her sentence from life to 20 years in prison after her attorneys showed that she carried the warrior gene and that her brain scans showed marked abnormalities in two regions – the insula, linked to aggression, and the anterior cingulate gyrus, involved in inhibition.

Could futuristic versions of such tests be conducted widely through the population at large? And would they give authorities a leg-up in predicting and preventing crimes? Would vast gene banks and advanced brain scans as ubiquitous as the street-level security cameras of today isolate the human powder kegs hiding in plain sight?

In a lively symposium on neuroscience and the law sponsored by the New America Foundation in October 2012, Jeffrey Rosen, professor of law at George Washington University, posed this disturbing scenario: ‘I am walking down the street and a mobile brain scan looks at my brain along with a picture of a training camp in Afghanistan. If I’ve not been there, I’m sent happily on my way. But if I have, my brain lurches a certain way, I’m taken off the street and carted off to Guantánamo and detained indefinitely as a potential enemy combatant.’ Would this be permissible under current US constitutional doctrine, Rosen, the moderator, asked.

That wouldn’t be allowed in the US as things stand now, said the panellist Hank Greely, a Stanford law professor.

‘We might see that kind of technology employed in North Korea,’ added his co-panellist Gary Marchant, professor of emerging technologies, law and ethics at Arizona State University.

‘There’s a real risk that the data that gets inputted is biased, or based on stereotype or overgeneralisations based on race and class’

And even if advanced technologies could prevent all crime, is this the kind of world we want? Given the massive privacy hit we have already taken in the internet age, should we let predictive policing finish the job?

It would be an especially onerous choice, given that predictive technologies can make devastating errors, indicting not criminals but also the innocent and pure of heart. A major worry is how algorithms are being constructed in the first place. Crime-scene data collected by authorities could be flawed and biased to focus on lower-income neighbourhoods and people of colour. And just because data is in the system doesn’t mean it’s correct. ‘There’s a real risk that the data that gets inputted is biased, or based on stereotype or overgeneralisations based on race and class’, said Hanni Fakhoury, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit digital civil liberties organisation in San Francisco. ‘It’s easy to ensnare innocent people into these things. Crooks talk to non-criminals, too, and taking lots of data on some people will inevitably capture information on people who’ve done nothing wrong other than to know someone caught up in the criminal justice system’.

In the US, one result would be violation of Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable searches and seizures. Let’s say police get a predictive tip about an area where a burglary is slated to happen. If a patrol car begins monitoring and a cop sees a man on the stoop of his apartment complex with a knapsack, that would not normally be enough to make a stop. But with predictive policing, it may qualify as ‘reasonable suspicion’.

Predictive policing could intensify the furore over Stop-and-Frisk, an NYPD policy in which individuals are randomly searched. The policy, which was adopted in the UK and recently called ‘unfair to young black men’ by the Home Secretary, Theresa May, could become even more controversial when predictive policing tools focus on specific neighbourhoods and the ethnic groups they contain.

Colleen Berryessa, the programme manager for Stanford University’s Center for Integration of Research on Genetics and Ethics (CIRGE), says that use of genomics might introduce more chaos still. As it stands, DNA swabbing is more of an art than a science, and DNA labs are rife with contamination, meaning that criminals and non-criminals alike could end up in a database, skewing our view of whom to suspect. It comes down to trusting authorities with a gauge as faulty as DNA.

Brain scans could be problematic, too. Referring to Rosen’s scenario of a would-be terrorist shown an image of a training camp in Afghanistan, Greely asks: ‘Even if you do react as if you have seen that camp before, is it that you’ve seen that camp or a picture of that camp? Or does that camp look like the summer camp your parents sent you off to when you were 11 that you’ve never forgiven them for?’ Certainly, we’d need to know a lot more than we know today before we can use the tools of neuroscience and genetics to pick off criminals in advance.

Understanding the root of all the violence could be as effective an intervention as cigarette studies and seat-belt research have been in the past

What’s more, predictive policing will never get to the root of the problem. Even when perfected, it can’t snuff the spark of criminal behaviour in and of itself. There might be a better way – perhaps channelling all that money and effort into serious research on gun crime. Understanding the root of all the violence could be as effective as cigarette studies and seat-belt research have been in the past.

Shattered people are suffering in failing systems. Relentlessly monitoring and spying on them will not tell us why crimes occur. If the US can spend a quarter of a trillion dollars on investigating, catching and imprisoning people, why can’t some of this monetary flow be redirected to mental health care for youth – the kind of intervention that involves therapists and activities, not cameras and swabs.

In fact, predictive techniques could be marshalled outside the realm of criminal justice, in childhood programmes for at-risk children as young as three or four. If a child has the warrior gene, if there is a metabolic problem that means the child lashes out violently upon provocation, perhaps early medication and psychotherapy could intervene, Marchant suggests. ‘You look at these [murder] cases and see there is so much suffering that could have been prevented,’ he told the symposium on neuroscience and the law. ‘But the problem is, we never had any markers to show a risk… [Now] we can pair those markers with treatment. We should put resources into finding these treatments and making it work.’

No amount of predictive policing can avert another Sandy Hook massacre. But if we identified future criminals and helped them, instead of locking them up, the Adam Lanzas of the world might be defanged. Used correctly, the right preventive techniques could save six-year-old children such as Dylan Hockley from a Hallelujah chorus, and would be an investment worth our time.