This summer I got married for the second time. Unlike my first wedding, in a town hall 11 years ago, this one was strictly informal. The ceremony took place at the Karaoke Pit in Berlin’s Mauerpark, a dilapidated concrete amphitheatre in the middle of the former no-man’s land between East and West Berlin. There were some 500 guests in attendance, most of whom I’d never met before and would never see again. My dress was black and I kept my sunglasses on. There were no bridesmaids, no public registrar, let alone a priest or rabbi, and no papers were issued at the end. Moreover, there was no bridegroom: I was, as it happened, getting married to my own self – with my husband and our two children watching from the front row.

I formalised my vows with karaoke, offering a musical and performative statement of intent in front of the assembled (and mostly unwitting) witnesses. This improbable 4.5-minute ceremony was the way I capped off a 10-week online course on self-marriage, which I took this spring. I was motivated three-quarters by what C W Mills in 1959 called the ‘sociological imagination’ – the capacity to discern the link between our everyday experience and wider society – and one-quarter by unbridled curiosity about the intricate workings of modern love.

‘Sologamy’ is the latest relationship trend not only in Europe and the United States but also Japan. A budding industry of self-marriages promises to make us happier by celebrating commitment to the only person in this world truly worthy of a relationship investment: our precious self. A variety of coaches worldwide offer self-marriage courses, including guidance through preparatory steps (such as writing love poems and composing vows) and orchestration of the ceremony itself.

While self-marriage has no legal power (you can’t normally do it in a town hall, at least not yet), it is open to anyone regardless of age and gender. I wasn’t – and am not – single, but that doesn’t disqualify me; my coach cheerfully confirmed that anybody, regardless of their situation, was welcome to learn how to ‘cherish’ and ‘love’ themselves. Still, most women (and it is almost always women) whose stories I read in blogs, Facebook pages and media reports were driven into self-marriage by the desire to emancipate themselves from the stigma attached to singledom and by the prospect of self-discovery. Some hoped that self-marriage would ‘heal them from a chain of painful break-ups’; others opted for it as a means of proving the worth of their lifestyles – and all of them were willing to learn how to love themselves ‘unconditionally’. Welcome to the 21st century, where we are no longer only ‘bowling alone’, to use the expression coined back in 1995 by the American sociologist Robert Putnam – we are marrying alone, too. So is this a sign of a radical new kind of independence, or a depressing totem to our self-absorption?

At its core, self-marriage is a classic rite of passage with three obligatory stages: separation, liminality and incorporation. The first stage – symbolic death – serves to break all ties that no longer serve you. The second stage is all about ‘discovering’ your new love for yourself, through techniques such as self-addressed love letters and poems. And, finally, the third stage, the big shebang: the wedding ceremony, meant to seal the bond between You and You, through your choice of self-declared vows.

As I progressed through these stages, my insights emerged less from any cold-hearted participant observation – that is, relentless browsing through blogs and closed Facebook groups – and more from my own feelings as I took part in the self-love exercises that were sent to me from California in regular email instalments. It began in earnest in Week 2, when I locked myself in front of the bathroom mirror, trying to perform a ritual called Soul Gazing. The instructions described it like this:

Look into your own eyes as if you were gazing into the eyes of someone you’re deeply in love with. See the depth, the mystery, the beauty, the tender vulnerability. Ask these eyes in the mirror: ‘Who am I? What do I love about myself? What are my dreams and fears? What do I long for? What do I need to hear right now?’

As I stared at myself, I had to work hard to focus on my face rather than on a dangerously lopsided tower of toiletpaper rolls and a pile of dirty children’s clothes behind my back. I was swiftly overcome by a bout of dizziness and, in fact, a kind of panic that sometimes seizes me on planes and in elevators. I don’t want to be alone here – I want to get out, quick! No, I did not feel like looking into my own eyes for another second; instead, if anything, I wanted to bury my face into someone else’s chest – my husband’s, my mother’s, my friend Eli’s – and feel their arms closing around my back in a close embrace.

Writing a love letter to myself was not dissimilar to Beethoven re-dedicating ‘Für Elise’ into ‘Für Ludwig’

A similar feeling overcame me a few days later, when I began ‘getting rid of ties that no longer serve’ – a task for Week 3. I enlisted the help of my friend Anna Semenova-Ganz, a performance artist who has devised a ceremony called Relationship Archiving. First, we spent a couple of hours rummaging through my house for every scrap of paper, every CD and every personal item reminiscent of a romantic escapade of one kind or another. All traces of my relationships, happy and unhappy alike, were to be treated with equal emotional detachment. Grammatically speaking, from present continuous they were to be moved into past perfect – in order to prepare me for the future indefinite (but bright). Then, once all those artefacts were piled upon my living-room table, one by one Anna started sealing them into individual plastic bags, numbering them and entering them into an inventory: ‘Silver stud earring with a coral inlay, worn on a first date with X’, ‘Wedding card from Aunt Lena’, ‘Note left by R before the end of the honeymoon.’

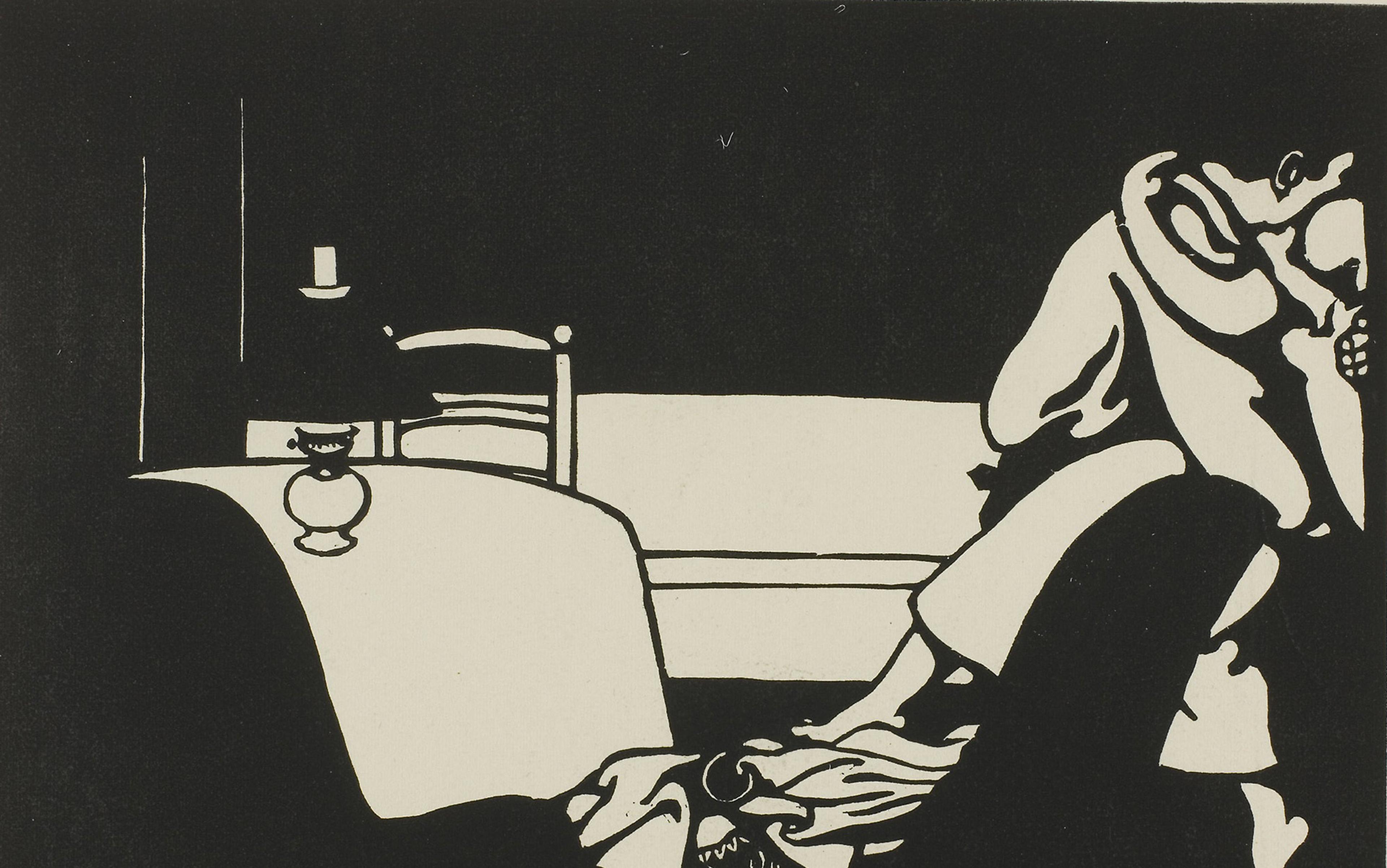

Purging relics from relationships past.

Clad in a white gown and white gloves, Anna looked like a mortician dissecting what used to be my love life. Under her hands, these tokens became lifeless bits and pieces which, indeed, no longer served me. The ceremony was meant to ‘purify’ me for the smooth flow of self-love – but instead, it just left me feeling acutely sad and lonely. Looking at the pile of sealed plastic bags, I didn’t feel ‘free’ to love myself; instead, I felt emptied of my very essence, that is, of the traces of love that others have left on my soul and my body.

Clearly, I was failing at proper, independent self-love. I still referred to other people to feel real, let alone loved. I’d still prefer to have another human being sitting across me at a candle-lit dinner (Week 8). I still felt that writing a love letter to myself (Week 7) was not dissimilar to Beethoven re-dedicating ‘Für Elise’ into ‘Für Ludwig’. How could self-marriage make someone happier if it was making me feel so lonely, I wondered. Yet an answer was creeping up on me: self-marriage – naturally, recorded with the help of a selfie-stick – is a telling incarnation of the contemporary great expectations about romantic love.

While it might seem contrary to the heterosexual, pro-natalist ideal of the white wedding, self-marriage is a logical – if somewhat grotesque – consequence of the romantic culture of the late modernity. Emancipated from the traditional social structures that gave life its shape and trajectory, urban Westerners now live in groups where romantic love has, to a great extent, replaced other meaningful relationships and experiences – extended kinships, lifelong friendships, collegial networks, neighbourhood acquaintances and religious bonds.

In The Normal Chaos of Love (1995), the husband-and-wife German sociologists Ulrich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim wrote (rather poignantly):

Love is glorified largely because it represents a sort of refuge in the chilly environment of our affluent, impersonal, uncertain society, stripped of its traditions and scarred by all kinds of risk. … weighed down by expectations and frustrations, ‘love’ is the new centre round which our detraditionalised life revolves.

The Beck-Gernsheims were right: love is increasingly mimicked and put on display as a driving force of human interaction. Flight attendants, waiters and nurses in the hospitals are expected to treat their customers with nothing less than love. By providing them with basic employment benefits, companies declare that they ‘love’ their employees. Craft beers, handmade jewellery, tie-dye shirts and organic marmalades must also be necessarily manufactured with this magic ingredient: an overpriced alcoholic beverage I recently bought in a Berlin hipster bar listed ‘Riesling, water, love, nothing else’ as its parts. ‘Love’ has become a kind of relationship flavour-enhancer, the glutamic acid that propels us to swallow what we otherwise wouldn’t – or what we should chew upon first.

The self-marriage industry caters almost exclusively to single, middle-aged women.

At the same time, at no point in history has there been such a proportion of single-person households as we now find in major Western cities. But the cultural turn towards singledom doesn’t signal loneliness so much as the rise of interconnecting technologies, personal growth and hedonism. Moreover, singlehood no longer necessarily equals the absence of romantic love; rather, this love can now be self-administered.

Self-marriage is one of the most telling examples of how ‘love’ is now deployed to reframe and pep-up a relationship that isn’t really romantic – such as the relationship with one’s self. The bulk of the practices, exercises and meditations offered in my 10-week course were, in fact, adopted from solid and well-tried philosophical, religious and spiritual traditions. But instead of grounding you in yourself so as to help you engage as a better person and citizen in the outside world, these ceremonies are purely internal. One might be tempted to say they are entirely narcissistic.

Week 3 of my course, for example, was dedicated to stoic meditations upon mortality, in which we were asked to imagine how we might feel if we knew we had only one week to live. Bringing awareness to the certainty of one’s own death is doubtlessly a noble and ancient pursuit. However, while Marcus Aurelius pondered memento mori as a way of becoming a better servant of his society, participants in the self-marriage course resort to this mantra in order to discover ‘who they really are’ and to focus on their ‘innermost aspirations’.

This seems to be radical self-indulgence masquerading as radical self-love

In a similar manner, Buddhist meditations, therapeutic writing and elements of performance were deployed as acts of self-love, rather than of reflection or analysis. Throughout the course, I was meant to write self-addressed love poems, dance my gratitude for who I am, and bestow gifts on myself in various kinds of ceremonies. The pursuit of unconditional love for oneself turns questions such as: ‘Am I a good person?’ into a series of affirmations: ‘I am a good person, no matter what.’ The most powerful tool of self-investigation, the inner dialogue, thus becomes transformed into a never-ending inner mantra of self-love.

Self-marriage also propels its adepts to elevate regular, garden-variety consumerism into a kind of courtship. In doing so, it soothes the alienated modern human’s need for ritual, for a communion with something greater than oneself. The blogs and Facebook pages of the newly or just-about-to-be self-wed suggest that the relationship with the self becomes the site of the same good old game: candle-lit dinners, walks on the beach, lace underwear, jewellery and spa retreats. Consuming attributes of love becomes love itself: a trip to Ibiza turns into a ‘pre-honeymoon’, a sojourn in Bali ‘a time of healing from emotional pain’, and a spontaneous shopping spree ‘a sacred gift to my Self’. This seems to be radical self-indulgence masquerading as radical self-love.

Japan, a country known for its romantic oddities, has taken the most radical approach to self-marriage as a reenactment of the obligatory luxuries of the Western white wedding. There, self-marriage is fully disengaged from spiritual pep-talk and is, instead, a mere performance: women throw solo wedding parties simply to dress in white gowns and get photographed with multilayered cakes. In a way, these upfront costume parties might be a more honest way of ‘treating oneself’ than a ceremony pretending to unite You with your Higher You.

The bride: Polina Aronson.

But perhaps I’m being unfair. After all, there’s no getting around the fact that society is still rigid and exclusive in its allocation of relationship entitlements. If it takes a single person calling her solo trip to a new restaurant a ‘self-date’ in order to overcome her own embarrassment, then we might have to revise our own beliefs about who should be allowed to do what. If mimicking romance is the only way to get or do things that should be available to everyone, then it is, indeed, possible that self-marriage is a canny and potentially revolutionary way of upsetting the social order.

Marriage has been increasingly turning from a conservative (if not retrograde) instrument of social regulation into a tool for emancipation of those groups who do not fit into the established reproductive ideal. Heterosexual middle-class whites have been increasingly opting out of marriage and establishing alternative types of long-term relationships, such as civil partnerships. However, to those less privileged – immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, people affected by poverty, and, notably, same-sex couples – marriage remains a reliable form of social mobility.

Married couples still enjoy preferential treatment in a number of areas, from tax to childcare, and marriage is still the most straightforward way to be acknowledged not only as a person but also as a citizen. In that respect the following holds true: what marriage equality has begun to provide the gay and queer community – that is, recognition and legal status – self-marriage might offer to a group often demonised and discriminated against: single women.

Naming their choice a ‘marriage’ allows single women to disengage themselves from the stereotype of an old spinster

It’s perhaps not surprising that the self-marriage industry caters almost exclusively to middle-age single females. Kinneret Lahad, a sociologist at Tel Aviv University, argues that women who assert being single as a rational and informed decision are often ‘depicted as too “choosy”, yet their choices are neither healthy nor authentic nor knowledgeable’. In A Table for One (2017), Lahad argues that in mass media and pop-psychology – two vital sources of relationship and sexual norms – women who prefer to be alone are referred to as being irrational at best, outright mad at worst.

Naming their choice a ‘marriage’ allows single women to disengage themselves from the stereotype of an old spinster. By writing self-addressed love-letters and vows, the brides-to-be are, quite literally, attempting to rewrite their biographies, turning a story of an old maid dying alone only to be eaten by animals – eg, Alsatians in Bridget Jones’s Diary or ants in Six Feet Under – into a tale of a self-governing woman who can enjoy solitude without suffering from loneliness. This is precisely the sentiment that the British comedian Ariane Sherine expressed in her 2016 article for The Spectator: ‘If we can’t find a knight in shining armour, we make alternative arrangements: the act of self-marrying is merely an extreme way of declaring that there is no hole in our lives.’

Honestly, though, I’m not convinced. The consumerist clichés, the stages of self-courtship, the act of pronouncing the vows all still come from collective, normative assumptions about how ‘good’ relationships need to proceed. Self-marriage might celebrate the individual, but it still deploys the traditional framework of a rite of passage, and uses it as a scaffolding for ‘self-growth’. As the meaning of ‘love’ is contested, we seem to cling to these performative aspects of romantic love ever more tightly. Rather than challenging conventions about what counts as a desirable lifestyle, self-marriage risks cementing them further.

Self-marriage is complicit with tradition not just in the way it borrows matrimonial terminology. What makes the practice such a true expression of modern romance is its stipulation that true love can be earned only by the relentless cultivation of self-sovereignty. ‘You are enough!’ is a formula drawn from the psychotherapist Nathaniel Branden’s The Six Pillars of Self Esteem (1994), but it has now made its way into guided meditation mantras, fridge magnets and T-shirt slogans. Westerners grow up with this message, in various forms. While on the surface it merely means something like ‘Be good to yourself’, the edict also has a strong normative undertow: you must be enough, all on your own – unless you want to count as needy and infantile.

The key imperative of Western romantic culture is that to be loveable one should, in the first place, stop needing other people’s love. Instead, we’re meant to nourish ourselves with everything necessary from our own resources, including affection, and not rely on others to do the job. This principle goes well beyond the esoteric world of sologamy. The dating site Match.com advises its clients that:

Always craving love is a cycle that must be stopped as soon as possible. By acknowledging the positive traits about yourself and learning to live for you, eventually, the love-craving cycle will end. You will begin to realise that you do not need love from others to be happy with your life. In the end you may be surprised; when you give yourself real love, so will others.

Hiding under all the injunctions to find and love one’s ‘true’ self is really an emotive meritocracy. The tale of obligatory self-discovery establishes firmly who is entitled to love and who is not; in particular, it ushers women into coupledom while simultaneously ordering them to guard their autonomy. Self-marriage becomes a way to have the cake and eat it, to get love you deserve – and the way you deserve it.

A self-married woman wrote on her Facebook page: ‘I had to spend quality time with myself. I had to date myself. Romance myself. Be intimate with myself. I yoga’ed. I cried. I also had to have some hard and vulnerable conversations with myself. Whilst reminding myself how beautiful and amazing I am.’

Tracy McMillan, an American author who went through several divorces before getting married to herself, echoed a similar sentiment in her TEDx talk in 2014. After the end of her third marriage, she realised that she had been ‘marrying everyone in sight except for the one person I really had to marry in order to have a great relationship’. Herself. After all this, self-marriage made her feel ‘whole’, she said.

To single women, particularly those who have gone through a history of abuse or trauma in their previous relationships, self-marriage might seem like a cure for the ills of a society. But it is difficult to shake the sense that it’s actually a palliative. While simultaneously accentuating and normalising the absence of the Other, self-marriage is unable to compensate for it – to a great extent because nothing can replace the gaze and touch of a loved one.

Self-help books might usher us into bubble baths and shoe shops but what we really need to feel loved is other people

Pop-psychologists, bloggers and relationship columnists never get weary of citing the ‘oxygen mask’ mantra, rubbing in the idea that taking care of oneself must always precede taking care of others. Latest neuropsychological research, however, provides a strong and convincing argument against this cynical extrapolation of emergency management to everyday life. In Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (2013), the neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman argues that our need for other people is even more fundamental, more basic, than our need for food or shelter. Because of this, our brain uses its spare time to learn about the social world – other people and our relation to them, not composing eulogies to our own selves.

This social wiring, Lieberman concludes, often leads us to restrain our selfish impulses for the greater good. Self-help literature might usher us into bubble baths and shoe shops, but what we really need to feel loved – and sane – is other people; that is, those other people who not only kiss us and hug us but also grump at us and hinder our ‘self-development’ with their judgments. To some extent, Lieberman’s findings echo Hannah Arendt’s assertion that we need a public to remain accountable and morally sane.

It is this acknowledgment of my need for the Other – and others – that I made into the foundation of my own self-marriage ceremony in the Karaoke Pit this summer. With a mike in my hand, I stood up, steadied my stomach, and sang to Melody Gardot’s ‘Worrisome Heart’:

I need a hand with my worrisome heart,

I need a hand with my troubling ways,

I would be lucky to find me a man

Who could love me the way that I am,

With all my troubling ways.

Most of my witnesses were random spectators who happened to be a part of the usual Sunday flea-market crowd hungry for finds, street music and unexpected performances. Climbing the stage in front of them and singing my oath about ‘needing a man’ was my own declaration of dependence: the dependence on being a part of the society, the dependence on something bigger than my own self.

When Gardot talks about needing a ‘man’, she probably means ‘a heterosexual dude’. But by ‘man’, what I meant in this moment, gazing at all those people (who had the decency not to whistle me off the stage) was ‘a human’ – another person, the omitted Other at my side, a friend and lover. Someone willing to work with my troubling ways, to go along with the Beck-Gernsheims’ idea of ‘the normal chaos of love’. Someone who could love me more than I could love myself.

Self-marriage is about attempting to hijack conventions about female singlehood; by doing so, it shows us the limitations of our own society. However, the truly revolutionary way forward would lie in aspiring for a society where affection, care and love would not have to be sanctioned by marriage alone but would be lived and accepted in all possible forms.

To liberate ourselves from the great expectations of a self-centred emotional meritocracy, we need to be more upfront about our need for attachment. The re-discovery and re-invention of attachment should pertain to all sorts of relationships, sexual or not, romantic or not, intimate, passionate or professional. Regardless of the context, practising attachment means being empathetic, being ready to experience pain, and acknowledging that we need others to be fully human.