At the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust centre in Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, children zigzagged between the duckponds like bees performing a cryptic private dance. The sound of children screaming makes my hands judder, in half-remembered horror. But today I could bear it, because there were geese to feed; they ran after me, pistoning seed out of my hand and leaving crescents of mud behind. As we left the feeding area, birdwatching hides rose up from the path: dark and shady, with silence inside and long windows giving out on to the marshy flatlands around the Severn Estuary. This was more like it.

Very quietly, we unhooked the wooden window clasps and let the pane down. My friend settled in with his binoculars, while I, chin-on-arms, watched the flat landscape – the low, ironed green, sprinkled with buttercups; the patches of water like gleaming fallen coins. We’d come in summer: a bad time for wetland wildfowl, my friend told me. In wintertime, godwits and dunlin and grey plovers come in from northern Europe and Russia to nibble on Britain’s mudflats. But when the weather gets warmer, many of these nice solid wading birds go back to the Arctic Circle, and leave Britain’s flat landscapes to themselves. That was OK with me. I was really here for the bare, stretched horizons of the wetlands. The flat places with nothing much to look at.

So I looked. And gradually the noise in my head got quieter. It always does, when I’m in a flat place. Something in me stills and lines up with the horizon.

Flat places are the ground that my mind is built upon. Wetlands, fenlands, stretches of shingle: I never get tired of their clear, straight horizons. Whenever I stand in a flat landscape, I feel myself becoming weightless. Without mountains or hills, there’s nothing to catch on my vision, or distract me. I’m freed from hindrance. I could rise up, I think, into the air and float.

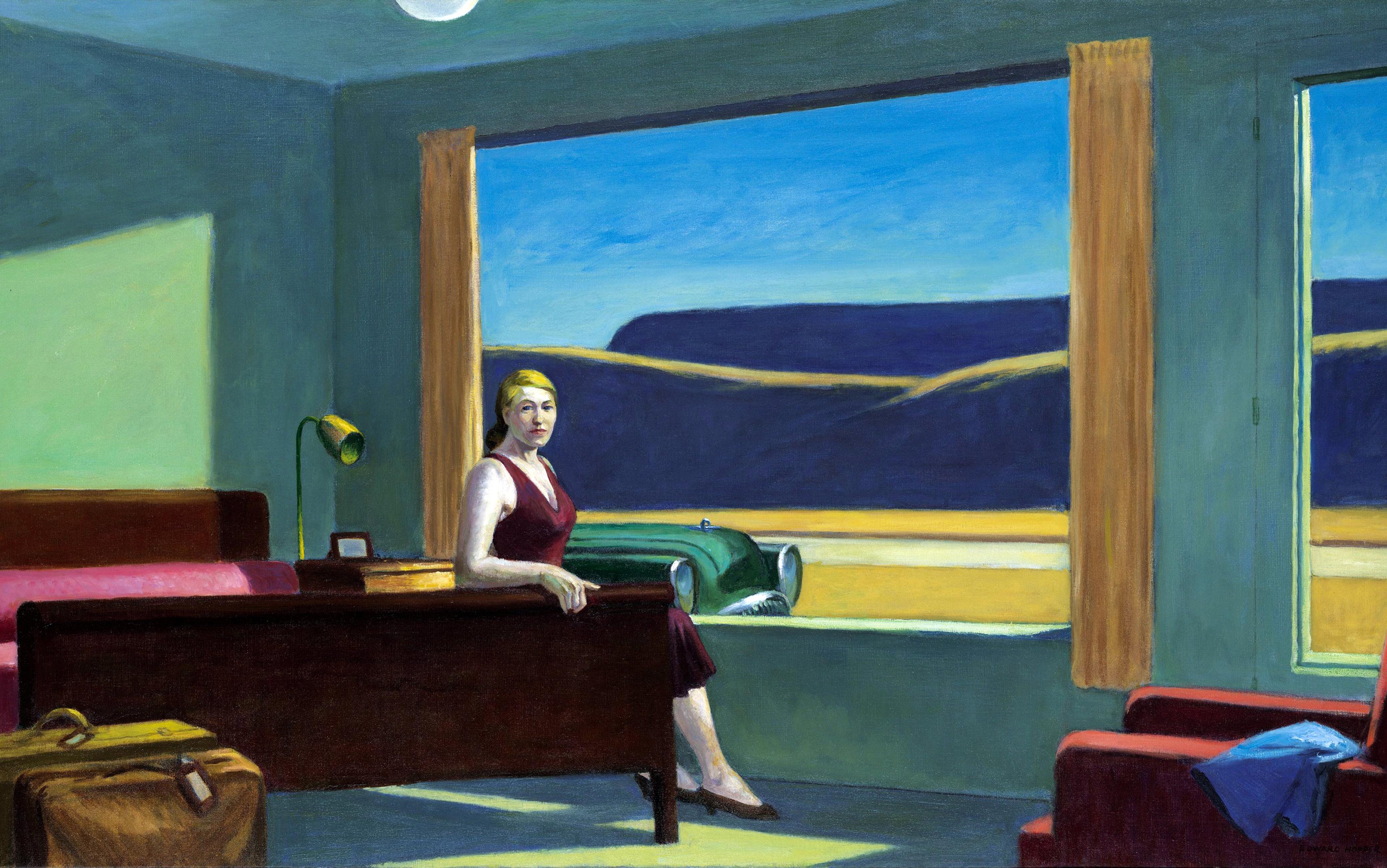

This isn’t a popular view, I know. I’m aware that people often find flat landscapes alienating. They can seem bleak, boring, even terrifying, because there’s nowhere to hide, and everyone can see you for miles. There’s no landmark to fix your gaze upon, and this makes it difficult to orientate yourself. That’s why people tend to prefer breathtaking mountains or lush forests or plunging valleys. Scenes with texture, that steer your vision comfortingly as you move from detailed foreground to rising background. People know where they are in varied, hilly landscapes. And they know who they are.

The experience of elation or awe in the face of a mountain is as old as literature. Gods lived on Mount Olympus, in ancient Greece. The Romantic poets climbed Mont Blanc to enthuse and gush. Loving a mountain means that you join a whole long line of mountain-loving humans, well-documented in novels and poetry and drama. Loving a mountain joins you to something bigger than yourself. I understand those preferences. But I am different. It is flat spaces that make me come alive. The lack of landmarks makes me feel I could do anything, or go anywhere I wanted. Uncontrolled and uncoerced: unsteered by other people’s beliefs or priorities. In a flat space, there are no focal points to fixate on, to force me to see some things and miss out on others. Looking out at the flat wetlands of Slimbridge, that summer’s day, my mind spilled out across the space like water over a floor: expanding, becoming sensitive and alive again, where life and work and other people had shut it up close.

My life has made me strange. I don’t mind admitting that. I was born and raised in an odd house in Pakistan, dominated by an arrogant and grandiose father. He was a celebrated doctor, and he had big ideas: so big that they absorbed us all and left no room for anything else. He was a genius, he told us. Other people were stupid: we should stay away from them. Especially other Pakistanis. He saw them as benighted by religion. My father was a Pakistani in love with the West, with the very surface layer of its cultural touchstones: Mozart, Vincent van Gogh, Gilbert and Sullivan. He painted a copy of The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Peletier (1872) by Edgar Degas, five foot by three, which he hung in the living room: the arms of the ballerinas bare and provocative and just a bit wrong in the elbows, where he’d misjudged the angles. Yet my father didn’t like British people any more than he liked Pakistanis; they didn’t defer to him in the way he thought he deserved. So he kept us away from everyone. We weren’t to speak to the neighbours, or visit friends from school. Our whole world was inside that house, our eyes trained upon him, braced for anything to happen. He might bring home chocolate. Or live turkeys. Or come in roaring and grabbing and throwing things. Anything could happen. And anything happened all the time.

Or maybe it was nothing. It felt like nothing: those long days cooped up in the hot dazed rooms. My father went out, and we didn’t. We were driven to school and driven back, and that was all. In the summers, when school was out, we went nowhere. There was nothing to do or look at or think about, except the floor, and the books we’d read and reread over and over, with the sound of the traffic shouting outside, and my uncles and aunts and grandparents shouting downstairs. Life was a bare landscape with nowhere to hide. I knew the other children at school didn’t live like this, but I couldn’t explain what this was. I lived my life in a daze. I wished there was more space.

‘You’re lucky,’ my mother said. White and British, she had moved to Pakistan to be with my father. All day she mopped and cooked and scraped up vomit. She roamed through the house, back and forth and back again, even more trapped than we were. ‘You’ve got enough to eat. You go to school. Do you know how many girls don’t go to school in this country? Should we take you out of school and just marry you off, so you can scrub floors for your in-laws all your life?’

My life in Pakistan, full of painful nothing, had left a flat landscape inside my head

I was lucky. And I went on getting luckier. I was lucky when my father disowned me, two weeks before my 16th birthday, and I fled with my mother and sisters to Britain. I was lucky when I got to go to school again, near my grandmother’s house in Scotland, and chose what I wanted to study, and could walk in the street by myself for the first time, and look at the sea and the grass. I was lucky when I got into Oxford to study English, floated by government grants and equal opportunity bursaries. But for some reason, throughout my 20s, my body didn’t seem to know I was lucky. It cried, and hurt, and clouded over, and numbed out. It was terrified of other people. It wouldn’t come close to them, wouldn’t be drawn to them, wouldn’t be caught up by passion. I kept falling asleep. I couldn’t want anything. And I couldn’t explain why. When I tried to share my feelings with other people, they couldn’t see what I saw. They couldn’t see the nothing of my life, which burned a thick stark line across my mind.

My life in Pakistan, full of painful nothing, had left a flat landscape inside my head. Not a bleak, dead one. That would almost have been easier. This flat landscape seared with painful livingness. It wouldn’t let me look away: kept me mesmerised by its agonised, intense emptiness. And it seemed more real than any of the strange world around me. Even in safe cosy Britain, where there were consequences for hurting your children and education was free, I sensed something sinister under the gleaming surface. Something stark and painful, and utterly relentless that refused to know how much its wealth and serenity was built on the pain of others, stripped for parts by white colonisers and taught to hate themselves.

It made it hard to be around people, in their happy ignorance. It made it hard to feel safe with them. So I lived in my own world, alone with what was real to me alone. I had no words to describe any of this. I loved my friends, but I couldn’t bring them in there with me. I knew the flat place was trying to tell me something important: something that Britain didn’t want to know. I just couldn’t work out what. And it hurt that no one else could see it.

When the wading birds go home for the summer, warblers from Europe and Africa take their place, eating, breeding and shouting seductively at each other. Little brown birds, mostly: flighty, quick, difficult to glimpse and to distinguish. Cetti’s warbler, Dartford warbler, grasshopper warbler. Garden warbler, marsh warbler, reed warbler, willow warbler, wood warbler, sedge warbler. So many and so alike, and in the summer the trees grow thick leaves to hide them from view. At Slimbridge, my friend peered at the reedy edge of a pond, binoculars to his eyes, muttering about a warbler, half to himself. I had no idea what kind of warbler it might be. Between the shivers of leaves, and the everyday swell and tremble of my vision, I could barely see the bird at all.

How do we see things? Usually we see what we know: what we expect to see. If there’s a mountain in the middle of a plain, we stop seeing the plain. The mountain ‘matters’; the plain doesn’t. Our cultures tell us what’s worth seeing and what isn’t. What counts as real and what doesn’t. In a flat place, we’re told there’s nothing to see. But the life I’ve lived has made me struggle to see what I’m supposed to: to focus on the right things, and ignore the wrong ones. What I can see instead, all the time, is the flat place.

As we went on along the path, the birdwatching hides fell away. Suddenly there was a high, raised bank on the left, a little furred comb of grass along the top, joining earth to sky. I knew what that bank held back from us: the flat stretch of the Severn Estuary, too muddy to step upon. The Bristol Channel brings up armfuls of brown mud, day and night: its funnel shape and sandy base turn the water heavy with silt. But in that mud lives delicious food for wading birds. Redshank, curlews, wigeon, shelduck, dunlin all gather to feast on ragworms and clams. If you cut a square metre out of the Severn mud, just 2.5 centimetres deep – like a big thick square of turf – it would contain the same number of calories as 13 Mars bars, all in snails and worms. There’s a richness in flat places, and the birds know it.

The smooth grass felt like hands running reassuringly over my head and down my neck

My friend was getting excited. Wading birds are his favourite, and they’d be out on the estuary. Birdwatching is a good hobby if, like my friend, you enjoy seeking focal points, ways of ordering your experience of nature. Giving things names. Yet there’s another kind of life, which is about living alongside things that have no names: memories that can’t be explained. The day something might have been put into my shoes, to smuggle it across a border. The day something was injected into me, at home, for reasons unknown. My grandfather, roaming the corridors with wide eyes, screaming and shouting for help. The men who came to the house and had conversations in whispers. And throughout, my father: mouth stretched with rage, throwing a metal box at me – its wires dangling and snapping – with a hatred even he couldn’t name.

Such a nameless life means that, normally, the longer I spend around people, the more I feel like I’ve been set on fire. But my friend is good at letting me be. He carries around my world respectfully, without prying, like a very polite bellhop with a lady’s handbag.

On our right were the inland flats: a river winding through, trees assembled at the back like an audience of mixed height, watching the bare stage of the level landscape, as I was: the prickling nothing that was happening all over it. Yellow flowers waved stiffly, out of sync, like buzzing made visible.

We passed through a tunnel of trees stretching over the path, almost touching overhead, and then – suddenly – the bank, which had been blocking our view, gave out, and there was clear flat land uninterrupted between us and the Bristol Channel. Salty grassland stretched out wide and, beyond, a little strip of sea. What was the land beyond, my friend wondered? Was it Wales? Already my mind was settling into straight quiet lines. The white shine on the green land and the smooth grass felt like hands running reassuringly over my head and down my neck. My friend walked ahead, towards the sea, and I took a photo of him, tiny on the path, in his pink shirt, with the blue sky arching over.

Four years ago, none of this – light, comfort, awe – would have seemed possible. I was 29. I’d just finished my doctorate, and got an academic job that would last a whole three years. This changed my life because it paid enough for me to start weekly therapy. I went into my therapist’s office – bony, exhausted and struggling to want to stay alive – and explained that nothing had happened to me, and could she maybe help, please?

My therapist was delicate and wise. She knew when to be offhand. Almost in passing, she mentioned complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD). I snatched up the term and went straight to books, to the internet, to strip it for meaning. Complex PTSD, I learned from the psychiatrist Judith Herman and the psychotherapist Pete Walker, is different from the sort of PTSD we associate with war trauma, or attack. It doesn’t turn on a single, traumatic memory, which marks the point when, for the survivor, the world turned from OK to not OK. In complex PTSD, the world may never have been OK in the first place. Complex PTSD is caused by ongoing events – often, where it feels like they’ll never end, or there’s no hope of escape. It’s worse when the traumas were caused by someone who was meant to take care of you. It’s worse if they start when you’re very young: too little to know what counts as an ‘event’. Or what counts as something being ‘not OK’.

I dug my toes into mud, traced shapes in shingle, and stared at long gorgeous horizons

This explained why the flat place in my mind had no landmarks I could pick out. No single terrible thing had happened to me, yet my whole life had been filled with a nameless terror and fear since I was born. I’d learned to dissociate to protect myself – to vanish from terrifying situations that I couldn’t fight or fly from. And that had been a wise response, said my therapist, to the situation I’d been in. Now, in Britain, a new way of handling life and its terrors might be more helpful. With my therapist, I started lining up what I could see, in my mind, with what I felt: sliding them up along the same straight horizon.

And I started going for walks in flat places. Morecambe Bay, in the northwest. The Cambridgeshire fens. Suffolk. Orkney. I dug my toes into mud, traced shapes in shingle, and stared at long gorgeous horizons in places that held themselves unapologetically in their strange refusal to be conventionally attractive to viewers, seducing them with hidden turnings or mystical peaks. In such places, I could be strange too: inscrutable, solitary, refusing to fit into an easy story that rose to a climax and fell to a satisfying ending. What was inside me found its counterpoint in the fens and mudflats. I was no longer alone.

From those flat places, drained and bare and empty, and which hid nothing – which, like me, couldn’t stop showing their damage – there rose up stories of more migrants from Asia and Africa. Not birds, this time, but cockle-pickers, farm-workers, a human zoo, a labour battalion. Migrants whom Britain does not know how to see; whom it prefers not to see. I wrote about these walks in my book, A Flat Place (2023). I put the flat place inside me on to paper, made it into a solid flat rectangle bound between boards, so that it didn’t need to surge up under my eyes any longer. I could show it to friends who loved me.

There were little birds out on the mud. I could see them but I didn’t know what they were. My friend had his binoculars out, and was muttering.

‘What do you think that is?’

As we relaxed into the space between us, birds started slowly to come into focus for me. I leaned in, peered through his binoculars.

‘I can see grey,’ I said. ‘And a bit of black. And maybe brown? Near the head?’

There was a pause.

‘Oh,’ said my friend. ‘It’s a wigeon.’

The plural of wigeon is either wigeons or wigeon. The males have brown-russet heads, peach chests, grey bodies.

It was the flatness, bigger and better than anything else in that landscape, full of brightness and clarity

We’d seen almost no one since we left the main centre, but now we stopped near a man who’d set up his camera on a tripod. His friend was sitting on the ground, nearby. They were both talking, neither of them listening to the other.

‘I was hoping we could have the soup at the centre,’ said the friend. ‘But I saw on the board, it’s tomato. I can’t stand tomato.’

‘Either a curlew or a whimbrel,’ said the cameraman, curving the lens round. ‘Earlier, the way it was moving made me think curlew. But now I’m not so sure.’

‘So I suppose we’ll just do sandwiches,’ said the friend. ‘I don’t know what they’ll have in the way of vegetarian though. If it’s just egg…’

‘This would be the right time of year for whimbrel,’ said the cameraman.

How can we ever know each other? How can we even know what we are seeing?

My vision ran over the clear brown land, mirrored with blue and white where the water had come in. It ran and ran as fast and as far as it wanted. It ran over the tiny birds, unseeing, over the wigeon and the curlews or whimbrels. It was the flatness I could see, bigger and better than anything else in that landscape, full of brightness and clarity. It didn’t have an existence for anyone but me, that day. But I could see it and felt I knew what it was.

Right at the end of the big map, printed on boards throughout Slimbridge, was a kingfisher hide, facing a river. When we got there, the hut was full, so we hovered waiting for a seat to become free. Who wouldn’t want to see a kingfisher? They are so beautiful and elusive: a rare, jewelled handful of blue and orange in among Britain’s collection of little brown birds. I’d seen a flash of blue down at a river, once, the year I was bones, but that was the closest I’d come. Once we were seated, my friend leaned next to me. This was allowed, because we were friends.

Intimacy is very, very hard for me. This is one of the most powerful and painful parts of cPTSD. At its root, complex trauma is relational trauma. It comes from being totally dependent on someone, for a long time, and being catastrophically betrayed by them – so catastrophically that they distort your sense of other people, and what they will do to you. Complex PTSD can mean feeling that other people aren’t real, or safe. That you are fundamentally different from them and can never share a world. Or, worse, that you are essentially defective and repulsive, and wise people should stay away from you.

Yet the only way out of cPTSD is relationship. It’s a cruel irony. The only way to start feeling better is to get close to people, and trust them: to have the experience of them not betraying you. It’s difficult, because everyone is busy and human and distracted, and makes mistakes. A little slip on their part will prove, beyond doubt, that you were right to be suspicious in the first place.

The third time – at last – I saw it. The kingfisher came out of the hole

My experience of cPTSD made it hard for me to imagine that anyone would want to be near me, ever. I always marvelled when my friends leaned in close or hugged me. But when I’m sure it’s safe and allowed – that I won’t harm them, or disgust them – I can’t take my hands off them. I drape myself over them, poke my chin into their clavicles, touch their heads. I’m sold. I’m theirs. I touch them again and again, to check they’re still real.

My friend put his binoculars over my head, and the lady sitting next to me told me where to look. The kingfishers were coming in and out of that little hole in the bank, she said. I tried to find it through the lenses. Twice everyone in the hide gasped and started clicking cameras, while I waved the binoculars frantically, unable to see what they were seeing. The third time – at last – I saw it. The kingfisher came out of the hole; it sat on the twig. I saw its orange tummy. I saw its little head turning, taking everything in, at peace.

I looked and looked until I felt guilty, and held the binoculars up to my friend. But he shook his head. ‘This is your first proper kingfisher,’ he said. ‘I’ve seen them before, lots of times. You enjoy it.’

I turned back to the bank, and went on seeing what everyone else could see, till the kingfisher went back into its hole and the moment was broken.

What I call the flat place inside me, now, is the feeling of intensity, of angry stubbornness: of knowing that I am real, and that what I know is real, even if the world can’t see it. I know what people can do to each other. What parents can do to their own children. Although the good moments get more and more frequent – when my friends and I find, even briefly, that we’re seeing the same thing at the same time – in the end, I wouldn’t trade the flat place for anything. Even if it means living mostly in my own world, alone with the memories without names that draw my eye endlessly but never rise into focal points in the flat place inside me. Shoes. A metal box. The scratch of a needle. The things I alone can see.