When I was 26, my world fell apart. I had just started graduate school and was travelling back and forth between Richmond, Virginia and Washington, DC because my wife was finishing graduate school in a different city. On one of those trips, I was doing laundry and found a note crumpled in the bottom of the dryer. It was addressed to my wife from one of her classmates: ‘We should leave at separate times. I’ll meet you at my place afterward.’

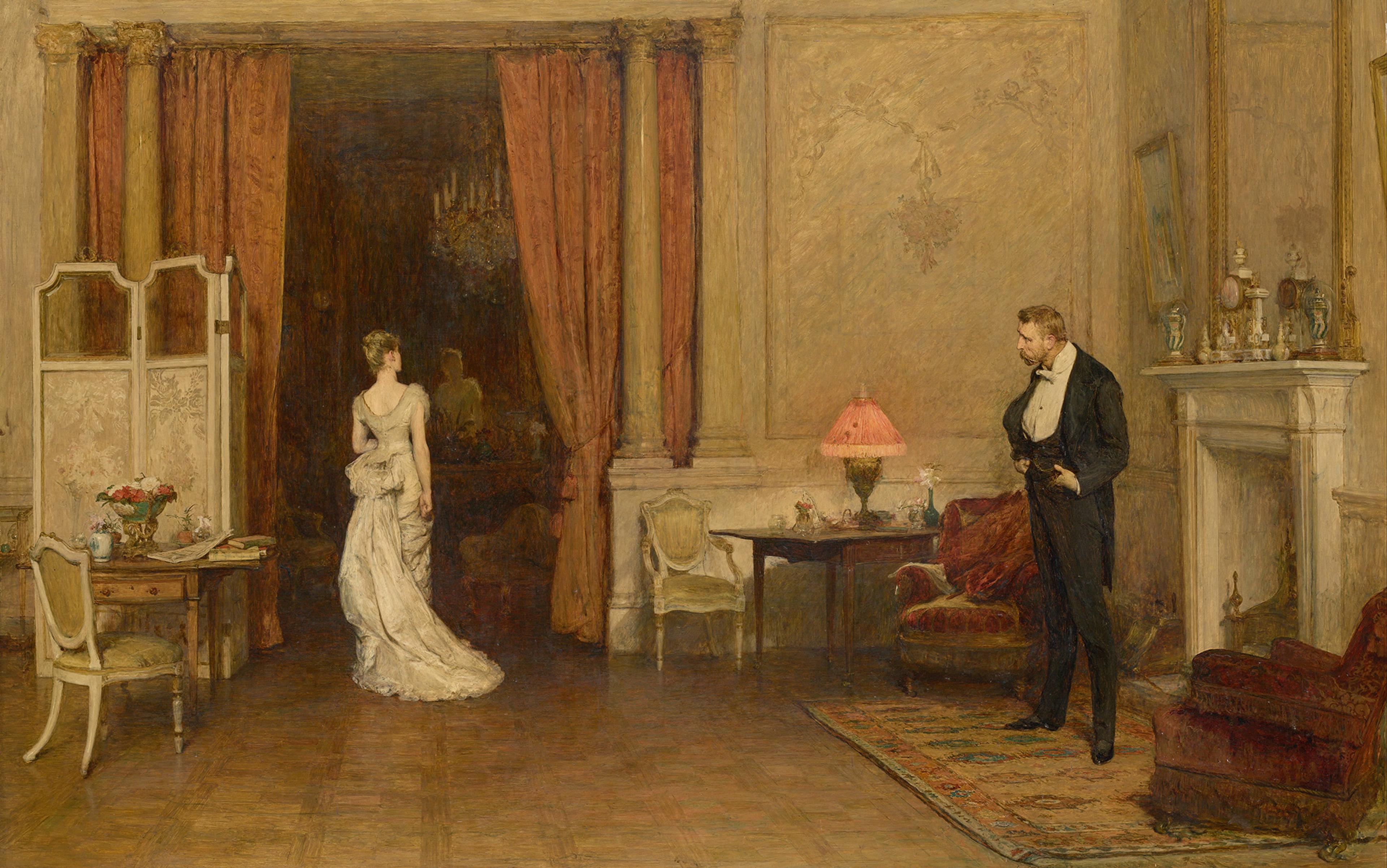

Although not confirmed until months later, my wife was having an affair. To me, it was a blow of monumental proportions. I felt betrayed, swindled, even mocked. Anger exploded in me and, over days and weeks, that anger settled into a simmering mess of bitterness, confusion and disbelief. We separated with no clear plan going forward.

Although this pain stabbed with an intensity I hadn’t felt before, I was certainly not alone. Many people experience similar hurts, and much worse, in their lives. Being in relationships often means being offended, hurt or betrayed. As people, we often suffer injustices and relationship difficulties. One of the ways that humans have developed to deal with such pain is through forgiveness. But what is forgiveness and how does it work?

Those were the questions I was working on at the same time that I was going through my separation. I was attending graduate school at Virginia Commonwealth University, and the clinical psychologist Everett Worthington was advising me. Ev is one of the two pioneers in the psychology of forgiveness, and from my first day he had me exploring forgiveness from an academic perspective (I left his office after our very first meeting with a two-foot stack of papers to review). I have since gone on to become a licensed psychologist and professor in counselling psychology at Iowa State University, specialising in forgiveness in psychotherapy settings.

Early work by Worthington and myself, and by others, identified what forgiveness was not. Robert Enright at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the other pioneer in the psychology of forgiveness, was instrumental in this work. For example, he and his colleagues distinguished between forgiveness and condoning, excusing or overlooking an offence. For true forgiveness to occur, they asserted, there needed to be a true offence or hurt, with real consequences. A good illustration might be the clients that Enright and one of his students, Suzanne Freedman (now a professor at the University of Northern Iowa), described in a paper: female survivors of childhood incest. For true forgiveness to occur in this context, they argued, the women needed to first acknowledge that a true hurt had been done to them as children. Denying their own pain or overlooking the atrocity would not be forgiveness. And, if it came, forgiveness would occur only after working through that hard reality of what had happened. Over many months and through challenging personal work, the women in the study resolved much of the fear, bitterness, anger, confusion and hurt, and achieved a remarkable level of peace and resolution regarding their past abuse.

Another main issue that became quickly apparent in the research was whether reconciliation needed to be part of forgiveness or not. For scholars and therapists like me who are interested in helping people achieve forgiveness for often serious offences such as marital infidelity and past abuse, forgiveness is restricted to an internal process. Thus, forgiveness doesn’t necessarily include reconciliation but is the internal process by which someone resolves bitterness and hurt, and moves to something more positive toward the offending person, such as empathy or love. In contrast, reconciliation is a process through which people re-establish a trusting relationship with someone who hurt them. This distinction became foundational in my own healing.

Although this distinction is important, it doesn’t mean that reconciliation is not a valuable consideration for those of us who see forgiveness in this way. Instead, reconciliation becomes a separate process, independent of forgiveness, yet important and valuable in its own right. This was a considerable balm to me in the months following my separation. Despite the pain, anger and confusion I still felt months later, I knew that I would want to move toward forgiveness at some point in the future. I didn’t want my past bitterness to infect any future happiness I might find in romantic relationships. I didn’t want to carry this burden the rest of my life. Instead, I imagined a time when I would want to set it aside and move on. My real fear, though, was that by forgiving I would necessarily have to reconcile with my wife or, alternatively, that if I didn’t want to reconcile, I would have to hold on to the anger. By seeing forgiveness as a separate process from reconciliation, new options appeared. I understood then that I might forgive or not, and I might reconcile or not.

A similar process has played out for many clients I have worked with. For example, I remember the palpable relief I sensed in a group of people I was treating when I brought up the difference between forgiveness and reconciliation. The members of this group were struggling with different offences, from being swindled out of thousands of dollars by an ex to romantic affairs and other betrayals. When I presented the possible distinction between forgiveness and reconciliation and we discussed how this could play out in their own experiences, I sensed a collective sigh. There was a weight lifted from the members simply through the understanding that to forgive didn’t necessarily mean to reconcile. There was a freedom the members experienced that opened our conversation and assisted their process toward forgiveness in a new and rich way.

For example, Jo (not her real name) was reeling from a fiancé who stole $10,000 from her and then vanished. There was obviously no way for Jo to work on reconciliation, even if she had wanted to, and yet with this distinction she could see how she might still move forward with forgiveness.

On the other hand, Maria, who was working to forgive her adult daughter for hurtful things she had done, wanted to keep the relationship; she was very interested in reconciliation. Understanding the difference helped her to see that she could work on both forgiveness and reconciliation in different ways to help heal her relationship with her daughter.

All in all, a proper understanding seems to help people embrace forgiveness and opens new possibilities for healing and growth. But how does it work and in what ways can people use it for their own benefit?

I have spent most of my academic career trying to answer this question. Specifically, I have studied ways to help people forgive others when they have struggled to do so. The science on this is still quite young, but there seems to be a common core of interventions that provide the most help in moving people towards a resolution of their hurts.

The first is a tried-and-true part of almost any psychotherapy: sharing the story in a safe and nonjudgmental relationship. Almost all established forgiveness interventions prescribe a time of sharing of the hurt or offence. This is particularly powerful in a group setting, in which participants share their different experiences with each other, and witness and hold each other’s pain. However, individual settings also provide considerable healing and understanding just from the telling of one’s story, without anyone trying to give advice, shut down negative feelings, or whip up feelings of anger and revenge in an OMG, he’s the worst person in the world! sort of way. Over and over again in our forgiveness programmes, participants tell us that one of the most important and effective parts is the opportunity to share with others what happened to them. They have said that the most helpful part was ‘knowing that others had similar struggles’, and ‘being able to vent – we could talk about things I couldn’t elsewhere’, and ‘That I felt listened to, really understood, and that I could get this off of my chest.’

This reaction is understandable given how hard it can be to talk about times when we have been hurt or offended. For some, it is difficult to share because there is so much shame and humiliation related to being hurt. Few people want to openly share times when they have been weak or mistreated, betrayed or rejected. There is much vulnerability in these stories. In addition to the shame that people feel, there is often the desire to avoid the pain associated with the hurt: If I share, I will have to relive the pain, and I might not be able to handle that. Interventions that can help people overcome these obstacles to sharing their pain and receiving support and validation can go a long way towards helping them recover.

Following a thorough retelling of the story, most interventions offer a time for people to consider the offender’s point of view. The goal is often to help people develop understanding or even empathy for the person who hurt them. There is great power in empathising, as there is great potential for harm.

Three years after finding that crumpled note, I pursued a divorce, and moved on with a new spirit of forgiveness

When done well, this part of the intervention helps people expand their perspective and gain a new awareness for the complexities of the events surrounding their hurts. It can lead to a broader view of the events that make the offence less about an evil person delighting in hurting them, and more about a complex situation in which someone made hurtful or bad decisions. This perspective-taking and understanding can open the door for forgiveness. An excellent example of this is work by Frederic Luskin, director of the Stanford Forgiveness Project, and Reverend Byron Bland, chaplain at Palo Alto University. In 2000, they brought together both Protestant and Catholic people from Northern Ireland, all of whom had lost family members to sectarian violence, and offered a week-long forgiveness experience at Stanford University in California. A large part of that experience was helping each group to see the other in a more human light, to move away from the bitterness toward the other group, and to leverage empathy to move toward forgiveness. As one participant who had lost his father reported: ‘For years I held resentment for Catholics, until I came here to Stanford.’

Of course, if done poorly or without boundaries, trying to develop empathy can be nothing more than blaming the victim and encouraging those who have been hurt to question or minimise their feelings or allow others to hurt them in the future. The important and difficult part of this process is in helping people to hold both the legitimacy of their pain while exploring other points of view. The goal is to help people to embrace their feelings as understandable and their reactions as justified, even while they gain an appreciation for the offending person’s perspective. This takes time and often shouldn’t be approached until a considerable period has passed since the offence. How much time is dependent on many factors, such as the severity of the hurt and the relationship one shares with the offending person.

In my own forgiveness journey, I made great use of sharing the offence and developing empathy. I received considerable help from several family members and friends and a caring counsellor who all heard my story without judgment about what I should have done or should do. Instead, they listened, they held my pain, and they let me express myself freely. My best friend bore the brunt of it. We had scheduled a short beach trip together the same summer that I found that note to my wife. As the timing worked out, I confronted her right before that trip, and she admitted to the affair for the first time right before my friend and I left on our trip. I spent two days on the beach in North Carolina spewing my rage and confusion, sharing story after story of all the little deceits and misdirection I was only now putting together. How he tolerated all that, I don’t know. But for me, it was an initial cleansing that helped lead to my ultimate forgiveness.

The next major part of my forgiveness journey was building empathy for her. This didn’t happen right away. In fact, it wasn’t really until years later that I was able to get a new perspective on it. It took that kind of distance for me to be humble enough to see the things that I had contributed to the relationship. I saw my part. I saw how she might have felt trapped by me, by family and by friends to enter into a marriage that looked enviable to outsiders but most likely was never quite right for her. I began to see how these forces might have influenced her to make the choices she did. I can now feel for her and how difficult and confusing all that might have been, and I can see that she probably had no intention or desire to hurt me. She felt stuck and she reacted to that experience. Out of this and the distance I now had from the hurt, I can say that I truly wanted what was best for her. I hoped that she would have a fulfilling life. Eventually, I chose to forgive my wife and I chose not to reconcile. Three years after finding that crumpled note in the dryer, I decided to pursue a divorce, and moved on with a new spirit of forgiveness and peace.

In addition to helping people to forgive others, researchers have also begun exploring ways to help people forgive themselves. Marilyn Cornish, a counselling psychologist at Auburn University in Alabama, and I developed one of those interventions, based on a broad, four-step model. The steps include: responsibility, remorse, restoration and renewal. We focused this intervention on helping people who carried considerable guilt for hurting others.

The general approach of our intervention is to help people take appropriate amounts of responsibility for the offence or hurt, identifying ways in which they are culpable for the other person’s pain. Out of this responsibility, they are encouraged to identify and express the remorse they feel. We believe it’s healthy to embrace our guilt and to place that feeling in a realistic context. From this point, it is then possible to move toward restoration. In this step, the person is encouraged to make amends, to restore damage done to others and their relationships, and to recommit to values or standards that they might have violated when hurting others. Finally, the person is able to move into renewal, which we understand to be a replacement of guilt and self-condemnation with renewed self-respect and self-compassion. This renewal is appropriate only after a true accounting of the offence. But once that has been done, we believe it’s beneficial for the person to move into a renewed sense of self-acceptance and forgiveness.

Self-forgiveness helped her face her children more honestly and move into a restored relationship with them

We have tested this intervention in one clinical study. For this, we invited people who had hurt others and wanted to forgive themselves to participate in an eight-week, individual counselling programme. Of the 21 people who completed the study, 12 received the treatment immediately and nine received it after being on a waiting list. Those who received the treatment immediately reported significantly greater self-forgiveness and significantly less self-condemnation and psychological distress than those on the waiting list. In fact, after controlling for their self-condemnation and self-forgiveness, the average person who received the treatment was more forgiving than approximately 90 per cent of people on the waiting list. Furthermore, once those on the waiting list received the treatment, their change in self-condemnation, self-forgiveness, and psychological distress mirrored the treatment group.

Several months after the conclusion of the study, I received an email from one of the clients. I’ll call her Izzie. She wrote to thank us for the counselling; she said it changed her life. Izzie entered the study because she was struggling with the implications of having had an affair earlier in her life. In addition to feeling lonely and disconnected from her family as a result of the divorce that followed, Izzie still struggled with the shame and guilt of her actions. This shame led her to withdraw from her children, and then to feel more guilt and shame at her inability to nurture them and be the mother she wanted to be. In her email, she detailed how the process of self-forgiveness helped her take responsibility for the events in an appropriate way and move through her remorse toward renewing her relationships. She told us how she was able to face her children more honestly and move into a restored relationship with them. Having given up and worked through her own self-condemnation, she was now free to relate to them in a new way and to be more the parent she wanted, and they needed her, to be.

Forgiveness, of others and one’s self, can be a powerful, life-altering process. It can change the trajectory of a relationship or even one’s life. It is not the only response one can make to being hurt or hurting others, but it is an effective way to manage the inevitable moments of conflict, disappointment, and pain in our lives. Forgiveness embraces both the reality of the offence and the empathy and compassion needed to move on. True forgiveness doesn’t shy away from responsibility, recompense or justice. By definition, it recognises that something painful, even wrong, has been done. Simultaneously, forgiveness helps us to embrace something beyond the immediate gut-reaction of anger and pain and the simmering bitterness that can result. Forgiveness encourages a deeper, more compassionate understanding that we are all flawed in our different ways and that we all need to be forgiven at times.

For more on difficult emotions and innovative therapeutic approaches, visit Aeon’s sister site Psyche, our new digital magazine that seeks to illuminate the human condition through three prisms: mental health; the perennial question of ‘how to live’; and the artistic and transcendent facets of life.