In the archives of the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York, there is an old postcard from the city aquarium of a large sea turtle with four boys straddling its back. The turtle lies flattened upon a pathway in front of a fence. At the feet of the children, near the animal’s front left flipper, is a messy coil of rope, presumably dropped after being used to hoist the turtle onto the pavement. At the time the photograph was taken, there had already been postcards published by zoos of children riding on the backs of giant tortoises from the Galápagos Islands. But this is something different. This is a large marine turtle, barely able to move itself on land. There wouldn’t have been any ‘riding’ here; just sitting on the back of an animal taken out of its tank for a photo-op.

The children, with faces ranging from something like happy through bored to skeptical, echo others in so many similar photographs from the late-19th and early 20th centuries. But as much as the boys are at the centre of this photograph, they are not the reason for it. It is the animal that is the interesting element. The children are only there to provide scale and to help the viewer imagine the extraordinary experience of sitting on the back of something so remarkable.

The animal in this case is a leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Leatherbacks, the largest of the living sea turtles with records exceeding 1,400 lbs (635 kg) – more than 500 lbs (227 kg) larger than the turtle in the photograph – are part of a line of turtles stretching back over 100 million years, and are easily distinguished from the other six living marine turtle species by their lack of a hard shell. Instead, leatherbacks have a soft skin covering a couple of inches of oily connective tissue with an embedded mosaic of small bones. Their backs, marked by seven long lines that join at the tail, resembled a harp, hence their then-common nickname: harp turtles.

Charles Haskins Townsend, the aquarium’s first director, proclaimed that this harp turtle – the second to have arrived at the aquarium in 1908 – was ‘the largest specimen … on exhibition anywhere’. He also noted that it wasn’t expected to live long, even though it had already broken the existing record by living two weeks. Just what caused the earlier deaths is not clear, but not eating and the mix of stress, poor conditions and injuries sustained in the captures, in the tanks and in moving them about are probable causes. Leatherbacks, creatures of the open oceans, do not appear to learn the limits of their enclosures well, and wounds on their noses and flippers from constant impacts with the walls can easily become infected. In the end, the leatherback is one of those animals that, to use an old euphemism, just don’t ‘do well’ in captivity. As for the turtle in the photograph, we don’t know when it died, but within a few months it had already been mounted for the Museum of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Can this photograph lead us to a larger history of public zoos and aquariums? It is, after all, just one moment, just one photograph. Still, it captures a timeless fascination with unusual animals – and the consequences of that fascination. Despite its age, there is so much about it that is recognisable, so much that doesn’t seem so different from what might be seen at a zoo today. True, major zoos and aquaria no longer produce postcards of children riding endangered species, but all kinds of up-close experiences, such as feeding giraffes and petting rays, continue to be offered.

The picture of the turtle and the boys, then, both signals a past and remains a part of our present. The photograph points to a more general issue with zoos and history: as much as there has been true change – and today’s large zoos are not the same places they were a century or even decades ago – the zoo’s basic, fundamental nature is the same. But this is not the story the zoos themselves tell us.

In the second half of the 19th century, during a time when it seemed that every major city in the world either had a large public zoo or plans to build one, the leaders and proponents of zoos began making a case about how their institutions were both different and better than the animal exhibitions of the past. Lumping together under the term ‘menagerie’ many different kinds of older collections of exotic animals, the advocates of the large public zoos of the 19th century claimed that, while earlier collections did little more than celebrate their usually aristocratic owners, the new zoos were different because they promoted science and learning.

If the menageries were assembled for the amusement of the few, the new zoos, it was argued, were built for the masses, with a new focus on knowledge rather than diversion. As Friedrich Knauer, the director of Vienna Zoo, enthused in a book about zoos for general readers in 1911: ‘Today, no one who wants to be taken seriously will doubt the educational and scientific roles of a zoological garden.’ Whereas the aristocratic menageries of the past were little more than follies, the ever larger bourgeois zoos that began to be constructed in the 19th century in London, Paris, Berlin, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Philadelphia and elsewhere were established, it was argued, to further science, education and public recreation. Built alongside the great museums of natural history and art, the operas and theatres, and even the sewers and subways, zoos became part of the civic infrastructure of growing and ambitious cities.

And yet, as the keen observer and critic John Berger noted more than 40 years ago in his classic essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’, however impressive the new zoos were supposed to be, they inevitably disappointed those who visited. An article from the Daily News in London from January 1869 makes clear that familiar disappointment. The piece announced plans for a spectacular new lion house that was being contemplated for the Zoological Society of London’s gardens in Regent’s Park, a place envisioned from its beginnings in the 1820s as a pleasant retreat where educated people could devote themselves to learning about the animals of the world. Describing the ‘dismal’ cages for lions and tigers at London Zoo, the Daily News concluded that ‘the cramped walk, the weary restless movement of the head, like a silent moan, the bored look, the artificial habits are as repugnant to the student of animal life as to the grand carnivora themselves.’

Far from the quiet sanctuary where the thoughtful could pursue their studies, the article describes ‘the long row of boxes, with barred fronts, before which the fashionables wait for the hyena’s horrid laugh, or watch the lion consume his modicum of raw meat’. The leadership of the zoo, though, was going to make a change: a new building had been conceived in which the large cats would be displayed finally in ‘a state of nature’. The eventual building that opened in 1876 was somewhat less than the hype – the cages were slightly larger, some were open at the top to the sun, and others were more round than square, but the bars were still there: the cages were still cages.

He realised that those who visited zoos preferred to see animals that didn’t look like they were in zoos

At the beginning of the 20th century, though, zoos did finally begin to look a little different. They began to evolve their missions, too. On the appearance side, in 1907 a zoo opened in Hamburg, Germany, that truly did come up with a novel and compelling solution to the longstanding design conundrums of the zoological garden: how do you make cages not look like cages? How can you build an exhibit in which the animals can be kept separated from each other, and the public, without the use of bars?

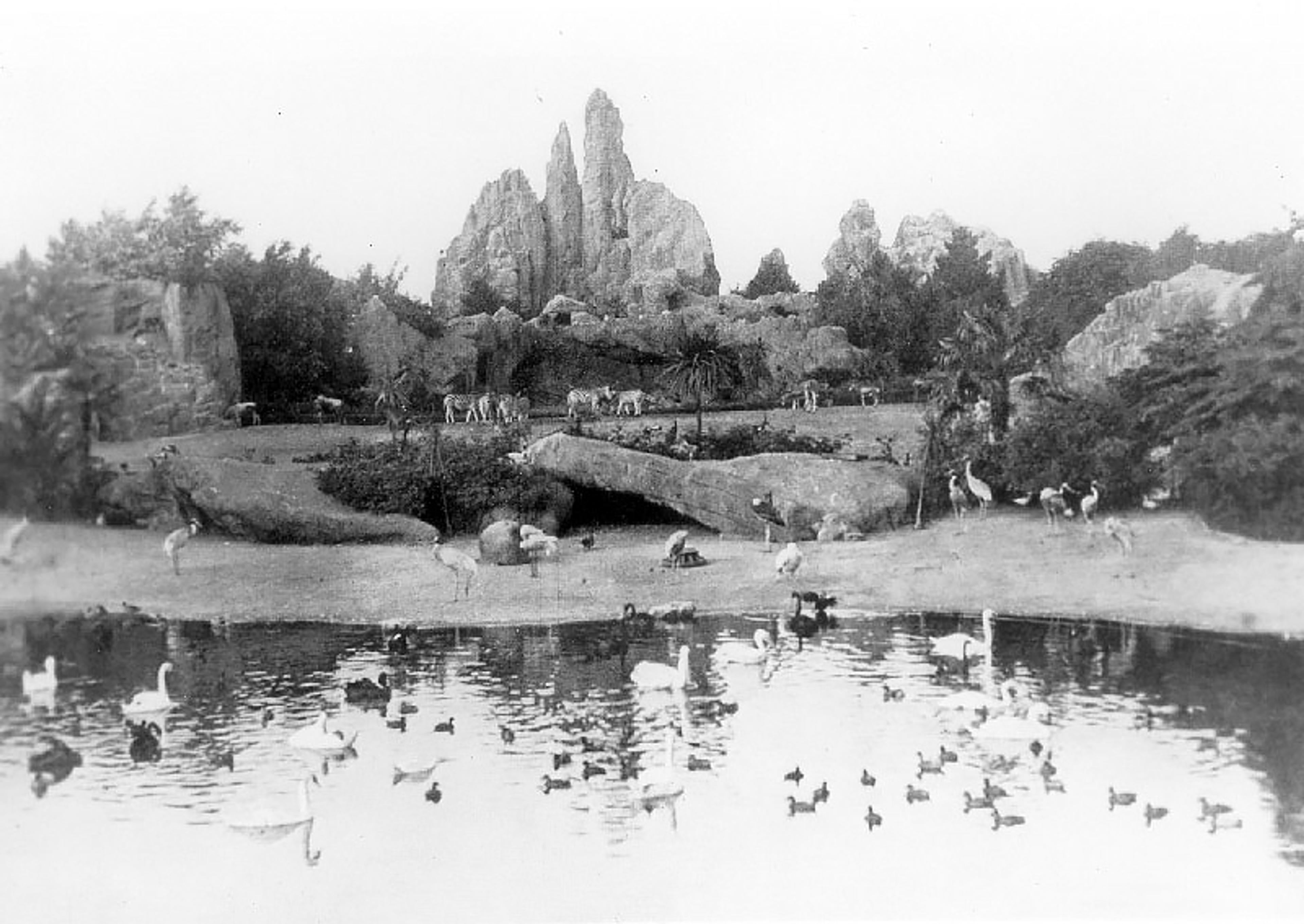

The panorama effect at the Tierpark Hagenbeck ca. 1925. Note the lack of fences. Courtesy Tierpark Hagenbeck, Hamburg

The vision, in this case, came not from an affluent, university-educated, scientific leader of one of the large municipal zoos, but from an entrepreneur, Carl Hagenbeck, who had left school at age 16 to start a business as an animal dealer in the rising commercial port city of Hamburg. After having sold thousands of lions, tigers and bears to zoos around the world, as well as experimented with extraordinarily popular travelling exhibitions of indigenous peoples, and launched several circuses that travelled internationally, Hagenbeck was in a position to know both what the public wanted and what animals were capable of doing. He also had the financial resources to build something entirely new: a zoo designed around often stunning and almost entirely artificial panoramic views in which animals seemed to be living beside each other in peace, while actually being separated from each other and the public through carefully designed and concealed moats, a layout he patented in 1896. The public and, eventually, the leadership of zoos in other cities took notice that Hagenbeck ‘freed’ the animals from their cages. Soon, nearly every zoo embraced his bar-less vision, and today’s cutting-edge ‘immersion exhibits’ can be traced directly to his realisation that those who visited zoos preferred to see animals that didn’t look like they were in zoos.

At the same time that Hagenbeck revolutionised their appearance, the mission of the modern zoo began to shift too. Beginning in the first decade of the 20th century with figures such as William Temple Hornaday, the founding director of the Bronx Zoo, the leadership of major zoos began to suggest that the modern zoo was committed to science, education and recreation. The increasingly evident perils facing animals in the wild meant that zoos could also become places of conservation.

Hornaday’s initial focus was to try to save the American bison from extinction, but soon he realised that zoos might play a role as something like arks, an increasingly popular metaphor, where animals could be safe from the dangers of the world. While wild animals were being destroyed in unprecedented numbers in what we are now used to calling the sixth mass extinction – the catastrophic destruction of species as a result of human activity around the globe – the 20th-century zoo began to be seen as a place where animals could live safely and happily. At the core of that vision, too, was that animals should reproduce. Successful reproduction soon became one of the classic markers used by zoos to measure their competence.

In Hagenbeck’s and Hornaday’s visions of zoos as refuges and not prisons are the origins of contemporary zoos. When our zoos saturate us with signage about the threats faced by animals in the wild, when they produce glossy reports showing their commitments to in situ projects to protect habitats, when they construct whole buildings to grow ‘awareness’ of the vital need for conservation in places such as Madagascar (while selling the most inexpensive hotdogs they can find and creating mountains of trash), we can see the long legacy of these thinkers.

It can be startling to realise how colonial ideologies embedded in the beginnings of modern zoos still present the rest of the world as dangerous for animals and in need of enlightened Western leadership. But the changes have not simply been a veneer. Even if it is disappointing to notice how little some things have changed, the focus on messaging about conservation, something that began a century ago, might well help visitors understand the challenges faced by our planet. It could also be true that actually seeing and at some level interacting with zoo animals does help some people – if clearly not most people – feel a deeper connection to conservation issues.

Perhaps more importantly, some zoos do indeed contribute substantial resources to international conservation efforts. The leader here has always been the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the parent organisation of the New York City zoos and aquarium, which contributes well over $100 million annually to global conservation programmes. In this respect, the WCS stands in a class by itself. Unfortunately, the true commitments to conservation of too many zoos can become obfuscated by their animal sourcing practices. When a zoo calls renting pandas from China a donation to conservation efforts, one can become quickly skeptical of these kinds of claims. Still, the 236 mostly US institutions accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums contribute more than $160 million annually to conservation projects around the world. Even if the lion’s share of that comes from the WCS, even if that total is well below one per cent of the total operating costs of these organisations, and even if a lot of that money is in partnerships designed to support the zoos’ own programmes, it is still a meaningful amount of money. Whether it is deployed in ways that actually make a difference to large-scale conservation issues is another question.

The turtle came to the aquarium in order to get people to come to the aquarium

The fundamental constant in most exhibitions of animals over the past couple of centuries, if not millennia, has been that people – not every person, but a great many – take pleasure in being close to animals. The impulse to capture, keep and show unusual, nondomestic animals seems, in fact, to go back as far as history itself. Whether they are a response to biophilia or some other hardwired part of human nature, collections of ‘exotic’ animals will be in our midst into the foreseeable future, just as they have always been with us. To put the point bluntly, people go to zoos today not because they want to support the conservation mission of the zoos, not because they are hoping to learn about which animal belongs to which taxonomic group, not because they are committed to supporting the scientific study of stress hormones in animal droppings, but because they think zoos are fun.

What they find when they go is often not what they expected or hoped. This is not a new phenomenon: this is the very nature of these kinds of places. This is why zoos have always argued that, while they might in the past have been bad, wasteful, poorly managed places, or destructive of nature, zoos today are better – and in the future, we are assured, will be better still. At a surface level the argument is true, but at a deeper level these institutions must forever struggle with the fundamental fact that while new missions – or what some would call justifications – have been added to zoos over the past couple of hundred years, the essential nature of the places as sites of human amusement that depend fundamentally on constraining the natural behaviours of other living creatures has not changed. Show me a zoo that builds an enclosure for a ‘boring’ snake – not for one of those huge, dangerous, spectacularly coloured ones – that actually meets the natural conditions of that snake in the wild rather than being a simple, small glass box, and I will be surprised. Then I will believe that the history of zoos has new stories yet to tell.

The leatherback turtle that lived for a few weeks in the New York Aquarium in 1908 is not a story of exception. It is the archetypal story of zoos themselves. The turtle was captured and then purchased by the aquarium not because it could flourish in captivity. It ended up in the zoo because it was a spectacle, because its size and the texture of its skin fascinated, because the name ‘harp turtle’ conjured poetic thoughts, because it was so big you could stick four boys on it for a photograph. It came to the aquarium in order to get people to come to the aquarium. The turtle died in the aquarium because, despite the goals of education, science and conservation, the core purpose of zoos has always been, and will always be, simply to entertain.