Divine visions, terrifying monsters, bizarre beasts. The intricate woodcut prints of the 16th and 17th centuries capture the fear and wonder of a world transfixed by invention and transformed by knowledge. Known as the early modern period or, more lavishly, the Age of Discovery, these years represent a temporal space that was a liminal world: transitional, ambiguous, straining against thresholds.

According to the philosopher A C Grayling writing in The Age of Genius (2016), this time was witness to ‘the greatest change in the mind of humanity than had occurred in all history beforehand’. Bloody battles – both intellectual and physical – were fought between the acolytes of science and magic, religion and mysticism, orthodoxy and heresy, democracy and monarchy. The path was violent and wending, but by the mid-17th century in Europe, humans had radically revised their place in the Universe, and were groping towards modernity.

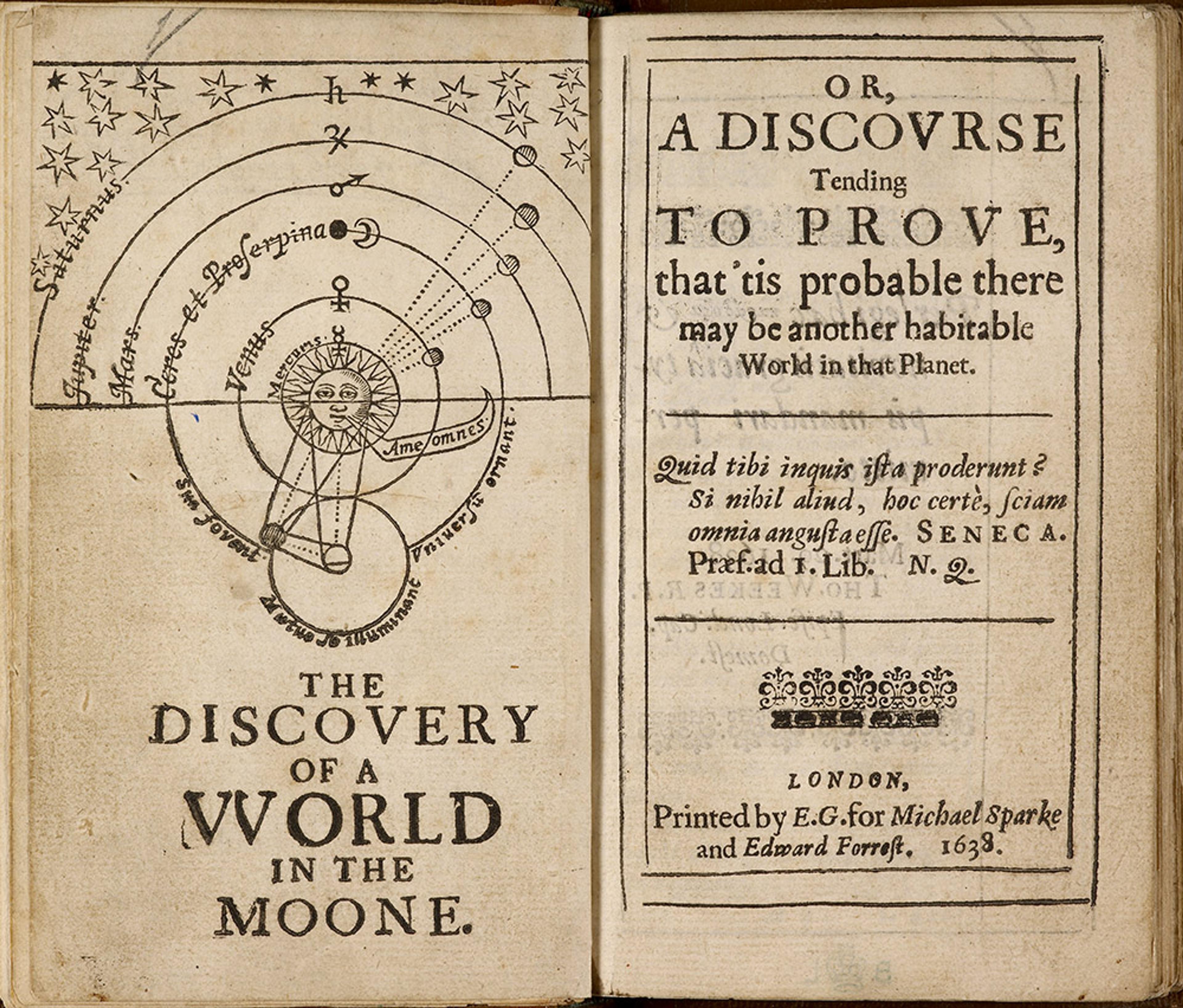

In 1638, just five years after Galileo was sentenced for the heresy of heliocentrism, a cheap little book appeared in London under the title The Discovery of a World Inside the Moone: Or, A Discourse Tending to Prove That ’tis Probable There May be Another Habitable World in that Planet. It featured a crude woodcut of the solar system with a sun at the centre, and amiably tried to reassure its readers that ‘how horrid soever this may seem at the first … it is likely enough to be true’. The controversy stemmed in part from Psalm 104:5, which says ‘the Lord set the earth on its foundations; it can never be moved’. The author of the pamphlet was John Wilkins, future brother-in-law of Oliver Cromwell; he hoped to foment dissent from the Catholic Church’s official line, and so to help shift the Earth from its foundations, socially and scientifically.

It would be a mistake, though, to see all this as a process of reason eclipsing ignorance. The wonderment of the era arose from the opening of new worlds, new structures for perception and experience that could be felt and beheld and probed but not yet fully grasped or contained. Superstition held fast while science grew rapidly. Exploration and intellectual achievement were suffused with a certain mysticism, as humanity sought to establish its ever-tinier place in an ever-expanding world. Magic and mystery had not been banished; something dark and sinister lurked on the edges, draped in the trappings of the occult. We would do well to remember that the milieu of black mirrors and Fairie Queenes was the same world that gave us the Renaissance and the first mass-market encyclopaedias.

Exploration branched out across multiple planes: geographically, via the conquest of new lands (at a terrible cost to local peoples); spiritually, through the observation of divine apparitions; and biologically, through the discovery of new creatures and civilisations. At the edges of maps, monsters and serpents were left to lurk and cavort in those unknown domains marked only as Terra incognita. Only one known surviving map, the Hunt-Lenox Globe, actually says ‘Here be dragons’ (in the Latin ‘HIC SVNT DRACONES’). But this romantic vision of what lies in wait in uncharted territory remains a perfect expression of our fear of the unknown – of that which lies ‘beyond the campfire’. There was known civilisation, and beyond, there were demons.

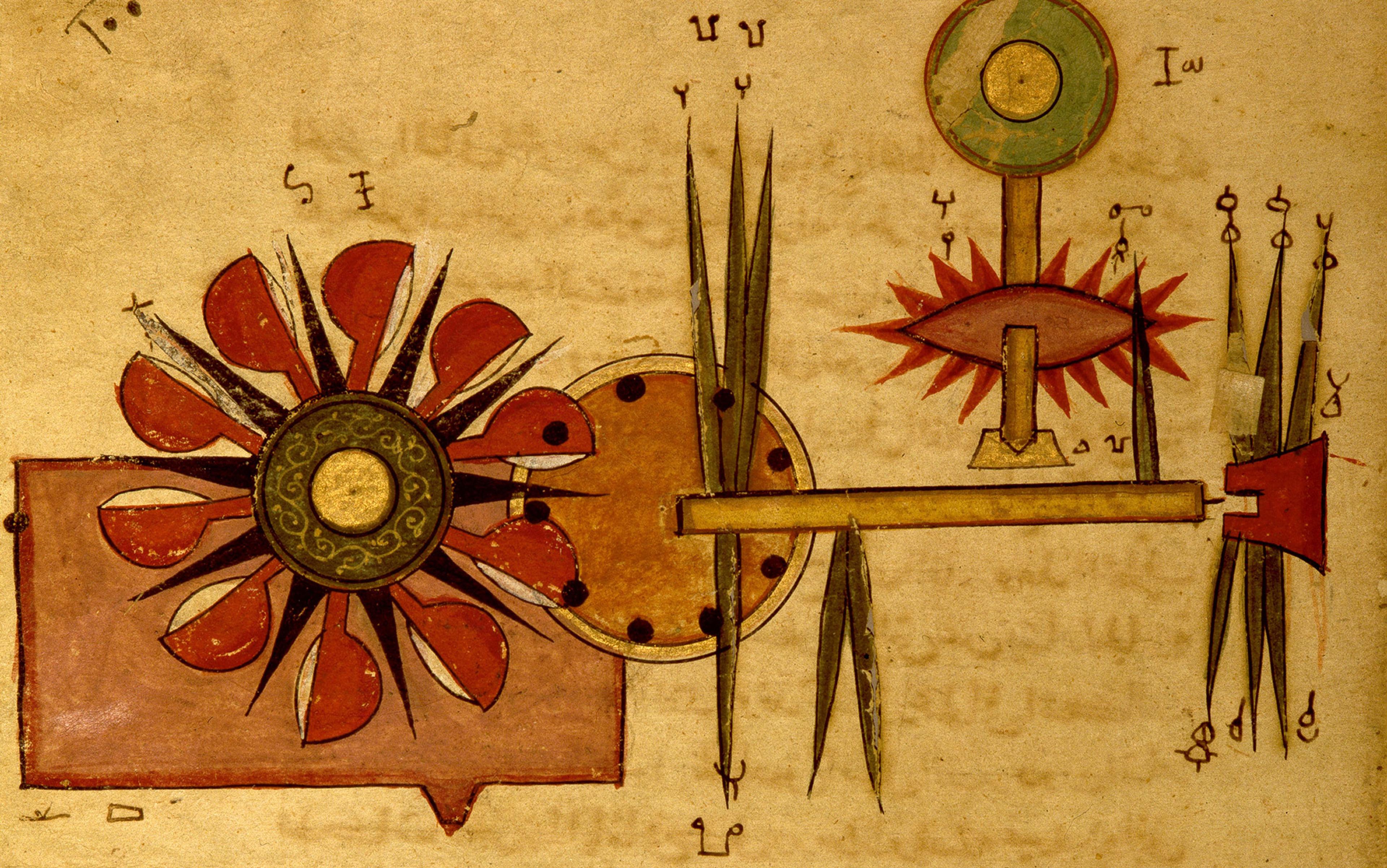

It was on the advice of her courtier John Dee that Queen Elizabeth took to the seas in the 16th century to create what would become, for better or worse, the ‘British Empire’. Dee was a mathematical genius whose expertise in astronomy steered England’s navy. He was the first person to rely on Euclidian geometry for the purposes of navigation; he also cast horoscopes for the royal family, practised alchemy, was rumoured to have raised the storms that helped defeat the Spanish Armada, and conversed with angels in the Enochian language. The black obsidian mirror that Dee deployed to summon spirits is now held by the British Museum in London, along with a crystal ball and several magical discs made of wax. Dee was also the primary inspiration for the character of Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and the eponymous character in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. If we take Dee at his word, ritual magic was a catalyst for colonialism.

The printed word was the medium for the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution, both of which rippled through Europe and beyond. In the 15th century, a few decades before Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama discovered new trade routes around the world, Johannes Gutenberg was perfecting moving type in his workshop in Hof Humbrecht. Before he invented his printing press, there were perhaps 30-50,000 books on the whole continent; less than 50 years later, there were as many as 10 million. By the end of the 16th century, 200 million were in circulation, rising to some 500 million books in Europe by the end of the 17th. And increasingly, they were illustrated.

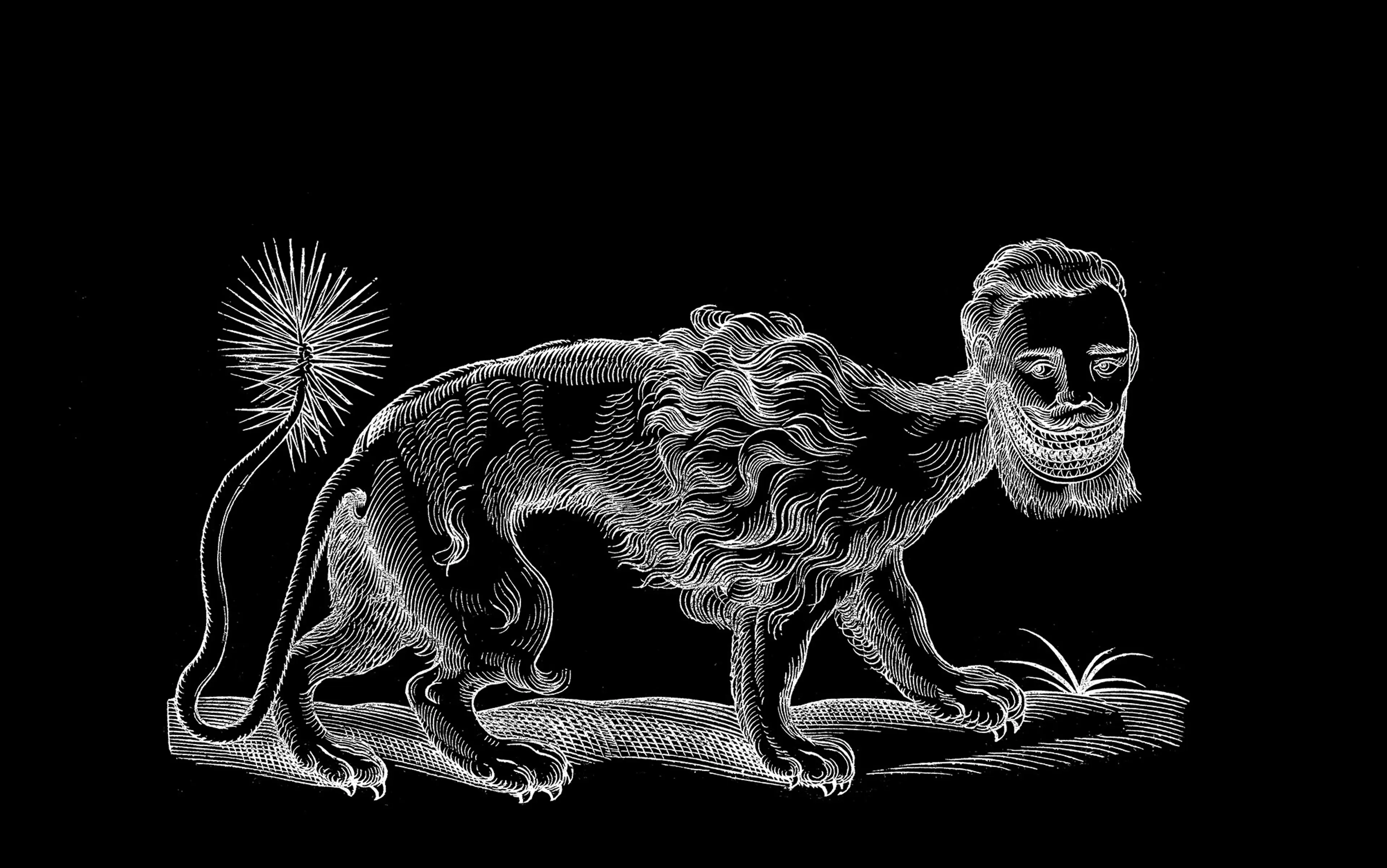

There is a feverish, nightmarish quality to the visual record of the time, with images that grapple with deep existential uncertainty – with what it meant to be British or European, male or female, even human or animal. As Europeans attempted to impose order at the chaotic fringes of their own knowledge, thresholds of understanding broke down further and further, like the proliferating fractals of mathematical chaos theory. New creatures were captured in ink as quickly as they were pinned down in the wild, but there was no time to grapple with the significance of each discovery. No image or text could possibly describe these unfolding marvels in their totality.

Broadsides, pamphlets and other cheap print advertised new discoveries, pushing gossip, ghosts and rumour

Woodcuts were the ideal thing to accompany Gutenberg’s movable type because both formats relied on relief-printing – that is, pressing a sheaf of paper onto an inked surface, before it is peeled away. Once made, it was cheaper and easier for a printer to reuse existing woodblocks than to commission new ones. Through the limitations of the medium, a distinct style arose. Shading and gradations of tone could be suggested through the use of delicate lines, but if the lines were too thin, the wood was likely to break, limiting the block’s potential for reuse. Two different markets therefore evolved. On the one hand, fine illustrated books were produced to a high standard and sold for large amounts of money to a professional audience. On the other, as printed material became cheaper and the market for ballads grew, a second economy of fantastically crude but familiar woodcuts expanded to fill the gap.

The new medium allowed unregulated information to flow like never before. Broadsides, pamphlets and other forms of cheap print distributed news to the masses – advertising new discoveries, fomenting political upheaval, and pushing gossip, ghosts and rumour. Ballad-mongers sold their wares at taverns and markets, and agitators distributed broadsheets through the streets and pasted them on walls.

In 1641, for example, an infamous ‘pamphlet war’ occurred in London between rival pamphleteers John Taylor and Henry Walker. Taylor was a ferryman with literary leanings, who styled himself the ‘water-poet’ and published prolifically. Walker was an ironmonger and a street preacher. After Taylor criticised independent preachers, Walker quickly shot back a reply attacking Taylor’s credentials. Taylor then took things up a notch with A Reply as True as Steel – its title mocking the ironmonger, and featuring a woodcut of a female devil giving birth to Walker. Walker’s response, Taylor’s Physicke Has Purged the Divel, upped the ante by showing a devil shitting in Taylor’s mouth, next to the caption ‘such is the language of a beastly railer / The devil’s privy-house most fit for Taylor’.

Common woodblocks circulated like stock images to pick out the key element of the ballad or story. The same devils appear in multiple tales, identical ‘merry boys’ feature on countless ballads about taverns, and matching monsters are seen on pamphlets published decades apart. These images were reused and remixed until they became an iconographic language to make sense of an uncertain world – like the memes of the early modern mind.

As Europeans explored further than ever before, for the first time publishers began to turn their travels into print and their sketches into woodcuts. The adventurer Thomas Coryat established the norm that if an Englishman was abroad and spotted a strange animal, it was not enough to simply describe the beast and move on – no, the proper response was to ride on its back and send a postcard. Two famous woodcuts showing Coryat astride an elephant and a camel, in full Jacobean dress, perfectly capture this strange meeting of one world and another. Coryat travelled through Europe, Turkey, Persia and India, covering considerable distances on foot, and his writings were hugely popular. He is also credited with introducing the table fork and the word ‘umbrella’ to England, and was a member of a literary drinking club known as the ‘Fraternity of Sireniacal Gentlemen’ that counted poets and playwrights such as Ben Jonson, John Donne and Francis Beaumont as members.

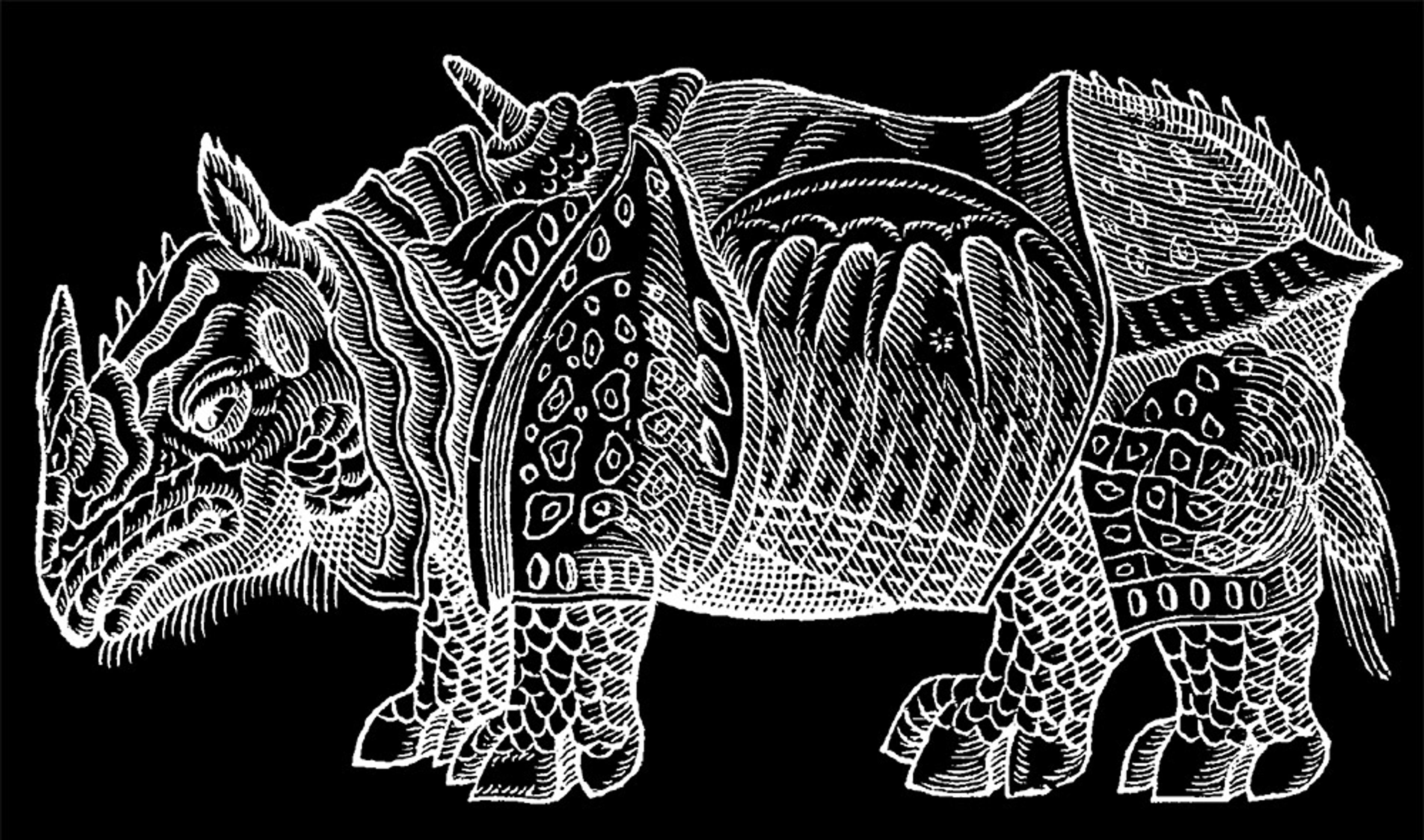

In zoological works, bizarre but real creatures such as the crocodile or boa constrictor appeared among a bestiary of plausible but mythical animals such as unicorns, hydras or dragons. The rhinoceros, in particular, straddled the border between the real and the fantastical in the 16th-century European imagination. In 1515, an Indian sultan gave a rhino to King Manuel of Portugal. It caused quite a stir, since it was the first of its kind to be seen in Europe since Roman times. When the German artist Albrecht Dürer created a woodcut of the creature, it captured the public’s attention, and was reproduced and plagiarised again and again in the coming centuries.

The animal known as the rhinoceros existed in a kind of limbo, where representation was more important than the object itself

Dürer himself had never laid eyes on the animal but refused to allow that inconvenient fact to get in the way of his vision. Instead he used a sketch and a description as the basis of the woodcut. The bulk of the rhinoceros is accurate, but is also encased in armour plates, with a small horn above its neck, scaly legs and cloven hooves – none of which exist in a real rhinoceros. But the fact it was anatomically askew did nothing to halt its popularity. If anything, they enhanced its allure. Variants of the image appeared under different artists’ names in multiple volumes, including mass-market bestiaries and encyclopaedias. Europeans regarded these as true representations for 300 years, and Dürer’s image appeared in school textbooks as late as the 19th century. The animal known as the rhinoceros existed in a kind of limbo, where the representation was far more important than the object itself.

A 1,000-page popular book known as The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents (1658) gives a flavour of the period’s dialogue with truth and imagination. Written by the cleric and author Edward Topsell, it veers between the remarkably accurate and the astonishingly far-fetched. Some of the images used are taken jarringly out of context. In one section, Topsell juxtaposed a text on hydras with an image of the Seven-Headed Beast from Revelations – something immediately recognisable to many readers – but offered no explanation for the strange contrast. Presumably it was simply the most relevant pre-made woodblock the publisher had in the pile.

Topsell himself expressed some skepticism about the reality of multi-headed creatures. But the point was not to sift fact from myth. Like many similar works of natural history, the author styled himself less as the considered informer and more the avid collector, the curator of a comprehensive bestiary. So much new knowledge was being produced, in such a narrow window of time, that it was better to distill the world’s wonderment than to destroy it with scientific materialism.

Eventually explorers returned with redrawn maps. Physical territory was ceded from the imagination, and the boundaries of the unknown moved closer to home. From the late-16th century, monsters became an extremely popular genre – especially for the authors of cheap pamphlets and broadsides, from which anthologies of Europe’s most monstrous creatures were compiled.

Many of these creatures were so-called ‘monstrous births’ – stories with a grain of truth at their core, perhaps, as science began to take better account of actual birth defects. Related to ‘monsters’, the study of ‘marvels’ and ‘prodigies’ became hugely popular in the 17th century. Books of prodigies might feature conjoined twins, humans born without limbs, as well as less dramatic, more easily understood, variations. This discipline became known as teratology, stemming from the Greek teras, meaning ‘monster’ or ‘marvel’, and logos, meaning ‘the word’ or, ‘knowledge of’. Slowly, fear was divested of its spiritual dimension and brought under scientific scrutiny.

Other entities were discovered in the world fully formed. The woodcut of an ‘ass-pope’, a creature supposedly unearthed in the Tiber river near Rome in 1496, first appears in Martin Luther’s incendiary pamphlet, The Meaning of the Monk-Calf at Freyberg (1523). The half-donkey, half-human was interpreted as a sign from God symbolising the corruption of the Pope and the Roman Church. Versions of the creature appeared in several works, with slightly different origin stories, but usually used as anti-papal propaganda. The woodcut was the perfect form for this type of telling and retelling, the viral communication of its era: easily made, easily reproduced, and easily copied by other artists.

A common example was the Monster of Ravenna, born in 1512 and described as possessing a horned head, the letters Y and X on its chest, the wings of a bat, hermaphroditic genitalia, and a clawed leg with an eye on its knee. When chroniclers of the monstrous dealt with this case, they layered moral interpretations onto these deformities. The horn represented pride and ambition; the wings, mental frivolity and inconstancy; the eye on the knee, excessive worldliness; the claw foot, robbery, usury and greed; and the ‘double sex’, sodomy.

The navigator Edward Fenton included the Monster of Ravenna in his 1569 text – titled, in a self-reflective if laborious fashion, Certaine Secrete Wonders of Nature: Containing a Description of Sundry Strange Things, Seeming Monstrous in Our Eyes and Judgment, Because We Are Not Privy to the Reasons of Them; Gathered Out of Diverse Learned Authors as Well Greek as Latin.

Fenton was an English soldier and explorer who joined Sir Martin Frobisher’s second and third expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage. Years later, he launched a trading expedition around the Cape of Good Hope, which he abandoned and instead attempted to crown himself King of St Helena. This proving infeasible, he engaged in some recreational piracy before eventually returning home, by way of Brazil, disgraced and mentally unhinged – he prevented mutiny by locking a crew-member in irons on the journey back. He somehow managed to recover some of his naval reputation by helping to defeat the Spanish Armada.

The would-be King of the south Atlantic’s book of ‘sundry strange things’ also included a monster born in Flanders ‘of honest and gentle parents’. It was described and drawn in hideous detail, no doubt to satisfy the morbid curiosity of sensation-seeking readers: ‘Cat’s eyes under the navel, cruel, and currish dogs’ heads at both elbows and knees, looking forward, the form of toad’s feet, a tail bending upward’… and on and on it goes. Fenton claimed it lived four hours after it was born, and died only after uttering: ‘Watch, your Lord is a-coming.’ It is always this multifarious, hybrid nature of the monstrous that woodcuts dwell upon – each animalistic aspect painstakingly observed, each deviation from the anthropos carefully catalogued.

These early modern woodcut bestiaries were a reminder that our place in the divine cosmos was perhaps not so fixed after all

It’s worth taking a brief diversion here into the theory of ‘hybridity’, which was embraced by postcolonial theorists in the 1960s to address the effects of migration and mixture upon identity. It was proposed that, as two cultures begin to merge, a new space is created, owned by neither the original culture nor the Other. Yet this new space comes to be viewed as representative of an unnatural, suspicious side of nature. Racial mixing, and more generally, the cultural mixing wrought by the efforts of early modern explorers, created a kind of hybridity that threatened such concepts as ‘European’ or ‘British’ – not as dramatic a form of boundary-crossing as bestial monsters, to be sure, but no less unsettling for those devoted to noxious ideas of racial purity.

On a long enough timescale, however, no such thing as purity exists. Across evolutionary history, there is only cross-pollination, generative pollution. In deep time, things look very weird indeed. Not only is Homo sapiens only one in a line of multiple Homo subspecies; they also interbred with the now-extinct Neanderthals in the area that has become Europe. (Thanks to genetic testing, I happen to know that I have 2.7 per cent Neanderthal DNA, which is actually slightly higher than average.) Delving even further back, humans and chimpanzees shared a common ancestor that lived around 7 million years ago, and so-called ‘missing links’ are found with some regularity in the form of ‘transitional fossils’. Pachyrhachis, for example, were ancestors of the snake that had a long serpentine body but two fully functional hind-limbs, while the earliest whales, Pakicetidae, were hoofed land-mammals.

While Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution would not appear for several centuries, woodcut bestiaries were an unsettling reminder that humanity’s place in the divine cosmos was perhaps not so fixed after all – that the Judaeo-Christian-Islamic schism between human and animal was not an uncrossable boundary. By blending the threshold, these images rendered chaos into mortal form. The classical god Pan, portrayed with the upper body of a man and the hindquarters of a goat, represents a version of the anxiety that man is just another animal. As the American writer and artist William S Burroughs wrote in Ghost of Chance (1991), Pan was the ‘God of Panic’, ‘the sudden, intolerable knowing that everything is alive … the knowledge that man fears above all else: the truth of his origin’.

Our desire for purity and essence runs very deep. But if you’ve seen many hundreds of examples, it’s clear that the early moderns also revelled in the sublime horror of it all. The prints might communicate dread, but there’s undoubtedly a frisson of exhilaration and perverse pleasure in there, too.

The boundary between male and female has been the traditional bedrock for social norms across almost all human societies. Yet in Europe of the late-16th century, even this supposedly bright line began to blur. In England, men began to wear their hair longer – inviting comparisons with women – and there were several high-profile instances of women defying convention, cutting their hair short, and dressing like men. These trends became a minor social and literary phenomenon, eventually reaching such a pitch in the early 17th century that King James stepped in to denounce ‘the insolency of our women, and their wearing of broad-brimmed hats, pointed doublets, their hair cut short or shorn’.

As David Bowie sang: ‘You’ve got your mother in a whirl/She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl…’ These rebel-rebels were satirised in a series of pamphlets, in particular Hæc-Vir, or The Womanish-Man: Being an Answer to a Late Book Entitled Hic-Mulier, Expressed in a Brief Dialogue Between Hæc-Vir, the Woman-Man and Hic-Mulier, the Man-Woman (c1620). It contains a dialogue between an effeminate man and a cross-dressing woman, who both initially mistake each other for the opposite gender. Beginning with theatrical, bawdy humour, it moves on to a powerful defence of women’s rights and a searing attack on ‘custome’ over ‘reason’. Despite this radical beginning, the pamphlet concludes with Hæc-Vir and Hic-Mulier denouncing the practice of transvestism, and agreeing to live as ‘true men and true women’.

It’s an interesting insight into the performativity of 17th-century gender. Many people were happy to inhabit a marginal space and test society’s conventions, while the establishment reeled in horror at such an affront to the natural order. In A Marvellous Combat of Contrarieties (1588), William Averell mentions the immodesty of those ‘Androgini, who counterfeiting the shape of either kind, are indeed neither, so while they are in condition women, and would seem in apparel men, they are neither men nor women, but plain Monsters’.

There was time for monsters to be enjoyed, especially in the ‘low culture’ of cheap plays, pamphlets and woodcuts

Some such monsters, like the pickpocket Mary Frith, found fame through flaunting their rebellion. Frith became one of the most famous women of her era, and a dramatisation of her life reached the stage under the name The Roaring Girl, or Moll Cut-Purse: As It Hath Lately Beene Acted on the Fortune-Stage by the Prince his Players (1627). The title was a twist on the almost affectionate term applied to young men who drank, brawled and caroused in taverns. The woodcut on the cover of the play’s pamphlet depicts Frith in the clothing typical of a ‘roaring boy’, complete with sword in one hand and pipe in the other. She, and others like her, actually enjoyed considerable freedom, even if their actions drew puritanical ire. There was a space for conventions to be broken and time for monsters to be enjoyed, especially in the ‘low culture’ of cheap plays, pamphlets and woodcuts.

The march through the early modern period was not a straightforward progression from ‘custome’ to ‘reason’. The British economist John Maynard Keynes captured this hybrid spirit when he wrote that ‘Newton was not the first of the Age of Reason. He was the last of the magicians.’ Mystical thought lingered even as science evolved, and the leading figures of the age straddled this boundary with no apparent problem. Wilkins, the author of Discovery of a World in the Moone, was also a mathematician, bishop, scientist, and a co-founder of the Royal Society. In Mathematical Magick (1648), he refers to Dee, Elizabeth’s adviser, and discusses mechanical marvels of the day before turning to the possibility that spirits and angels could help humans to fly. Later, Wilkins tried to devise a universal language, which in turn inspired the Jorge Luis Borges essay ‘The Analytical Language of John Wilkins’ (1952).

Wilkins and Dee capture the yearning for knowledge and the love of mystery that run together through the early modern period. For the first time in history, tremendous discoveries and ruminations could filter through to the general public via the medium of print. Science and spirits, mathematics and magic: writers and publishers could take these elements and spin a story, or craft an image, to satisfy any market. Woodcuts gave form to what lurked at the fringes, and also sated a desire for wonder. Like Dee’s magic mirror, they offered a reflection of the viewer’s mind and soul. In the inky darkness, there was a whole world ready to pour forth.