As I walked the green miles of the Undercliff where the French Lieutenant’s Woman met her lover, there came a change of air. The dense undergrowth was obscenely verdant — bees worrying at pink rhododendron, peacock butterflies crossing my path — and now and then I’d burst out and find I stood at the cliff’s edge overlooking the sands of Golden Cap. It was impossible to imagine any other human setting foot where I’d set mine. When the path sank into a darker place and I found myself among the ruins of a great house, I shivered as if I’d grown cold. A high, pale-stoned wall with windows pointed at the upper edge put a black shadow at my feet, and fragments of its foundations were scattered about like broken teeth. A little further on I could see the wet black lip of a well. There was a thick silence.

All that day I’d seen seabirds wheeling overhead. One or two chaffinches with their peach breasts blinked at me from the hedgerow. In the ruins, nothing but a magpie pecked aimlessly at the dust. Brambles put out creepers that caught my ankle as I passed, and scraps of cloud passing the empty windows had the appearance of blind faces mouthing at me. What had been a day of brightness and beauty altered all at once; I felt inexplicably anxious, as if all those broken stones were conveying to me the memory of something dreadful they’d once witnessed. I stood there a while. What I felt was not quite fear, but a disquieting thrill. Then I moved on. The path grew brighter. I forgot my unease.

Years later, I sat among the ruins of the Roman Forum, in the shadows of the Temple of Castor and Pollux. I inclined my head, convinced that, if I only tried hard enough, I’d hear the bare feet of vestal virgins padding through the marble halls. I sat because I could not stand: my mind could not comprehend the sublime magnitude of what I saw, and my body had given up in sympathy.

It was to be a long time before I understood that what I’d encountered there in the Undercliff in Dorset, and again in the shadow of a Roman cypress, was rooted in a tradition as pervasive as incense smoke, and every bit as hard to grasp.

I’d lay good money that you’ve used the word ‘Gothic’ in the past month or so. A swift survey of popular culture reveals that the Twilight novels of Stephenie Meyer are Gothic, as is the style (both in song and dress) of the indie rock band Florence and the Machine. UK Vogue magazine reported on 2012’s catwalk trends as ‘high on Gothic glamour’, and there were corresponding articles in style magazines on how to perfect a Gothic maquillage of pale cheeks, smoky eyes and blackberry lips.

Vasari the tastemaker purses his lips and makes a terse little note on its failings: it is an example of that most deplorable of styles

Tim Burton’s films, as we all know, are Gothic; so are the red-carpet frocks of his wife, the actress Helena Bonham Carter. The British novelist Cathi Unsworth’s crime-noir Weirdo (2012) is billed as ‘a retro-Gothic thriller’. Pallid teenagers in riveted leather coats are Gothic. Sarah Waters’s second novel, Affinity (1999), is neo-Victorian-Gothic. The new album from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Push the Sky Away (2013), is, they say, ‘Goth-blues’. A new paperback edition of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) shows on its cover a bitten scarlet strawberry against a black background. This, apparently, is also Gothic. What draws together a wine-dark lipstick stain, a glittering boy-vampire, a tale of murder in a Norfolk seaside town? What do I mean when I say ‘Gothic’? For that matter, what do you mean?

We can use Google’s Ngram service to track the word’s published popularity from 1500 to 2000, plotting it against other expressions in use over the same period. With ‘Gothic’ in the ascendancy, so too were ‘villains’, ‘ruins’, ‘madness’ and ‘terror’; together, these surged in use from 1750 and peaked towards the end of that century. After 1850, more nebulous qualities began to creep up on the villain in his castle: words such as ‘eerie’ and ‘uncanny’ grew in currency. Intriguingly, at this point the Gothic begins a decline — and then, as if required for new purposes, it rallies again.

The Ngram exercise is diverting, but ultimately touches only at the periphery: it is like trying to define a planet by its moons. To get at the heart of the matter, it is necessary to cross half a millennium and stand beside the Italian art historian Giorgio Vasari in the shadow of Reims cathedral in 1535.

Exquisite in his velvet coat, Vasari appraises the high ribbed vault and the flying buttresses, the spitting gargoyles and the glittering rose window, the saint-pierced façade and the towers that would have pleased Babel’s townsfolk. In its scope and beauty, it is surely the epitome of mankind’s achievement, bought at incalculable fiscal and human cost. But Vasari the tastemaker, the ultimate Renaissance man, purses his lips and makes a terse little note on its failings: it is an example of that most deplorable of styles — the Gothic.

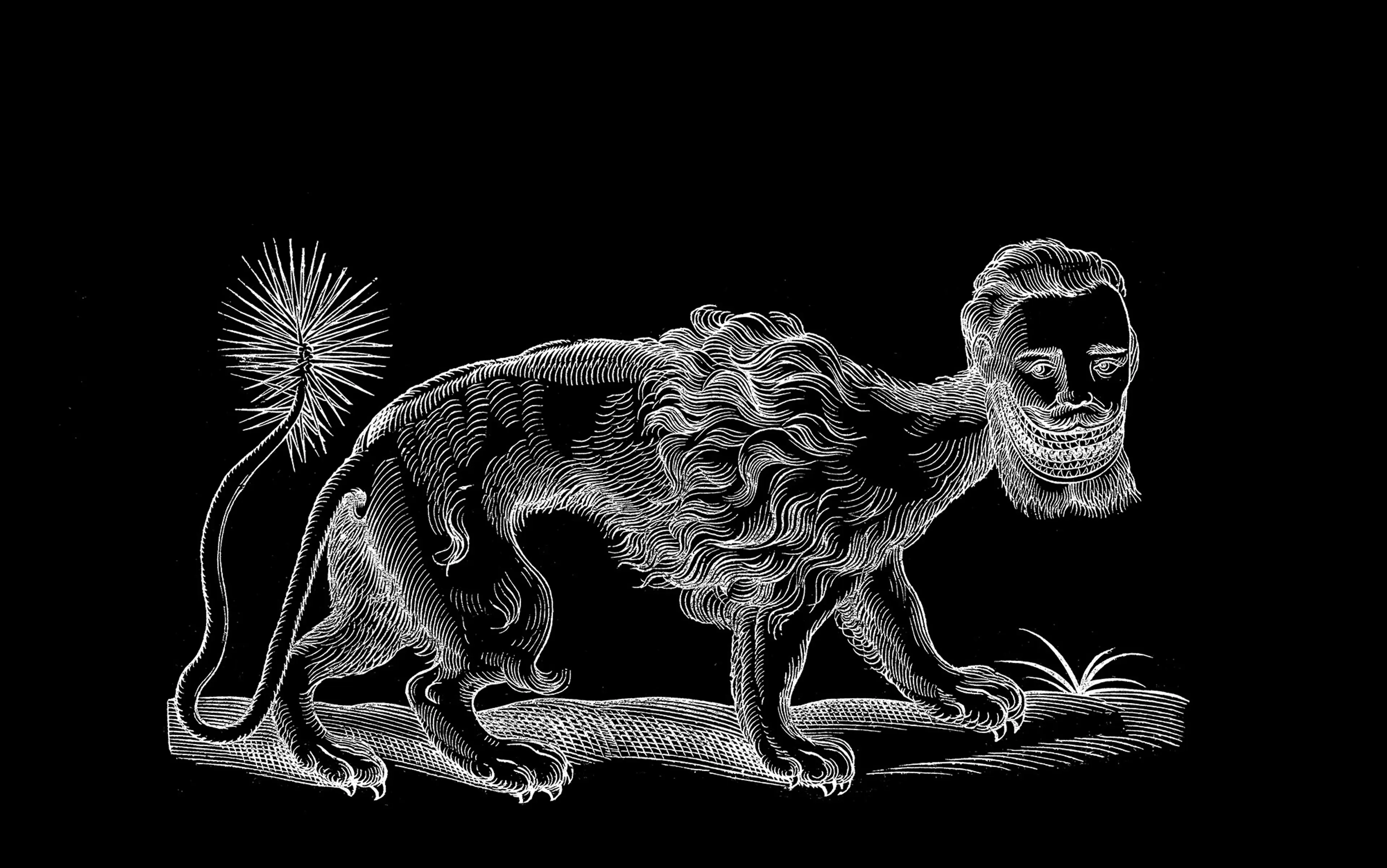

To Vasari, who prized Classical principles in architecture as in all other modes of art and thought, the cathedral — from its deep labyrinth to its almost incomprehensible height — was a piece of barbarous savagery. It struck the visitor dumb with awe, provoking not clarity of reason or a Platonic appreciation of beauty, but a kind of insensate thrill. In raising the spectre of the Goth, Vasari was recalling — with all the terror of inherited folk memory — the Sack of Rome in 410, when Germanic tribes dismantled the city that was the centre of the world. The ecclesiastical architecture of the Middle Ages represented as much a threat to Renaissance ideals as the desecrating Visigoths did to that ailing Empire more than a thousand years before.

So much for origins, buried beneath the stones of the Forum and carved in the lintels at Reims. Does Vasari’s criticism have anything to do with villainous monks with erotic habits, black lace dresses in the pages of Vogue, or talc-faced teenagers sporting their gilt crosses down by Whitby Bay, the home of Dracula? To understand the potency of the Gothic, it is useful to think of the word as having ‘gone viral’, in the truest sense. Like a virus, it shifts and mutates across the centuries, adapting readily to context, exploiting the weaknesses of its host. Its symptoms are elusive, and often seem contradictory.

Vasari’s notion of the Gothic assumed that those desecrating Germanic tribes were culturally coarse, with none of the Classical refinements in philosophy, society or art. Move on to the Enlightenment, and the symptoms of the Gothic have subtly altered. To liberal Whig ideology, the Goth was not a symbol of barbarism and destruction, but of a libertarian and democratic political lineage reaching back from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 through the Saxon Witenagemot to the Sack of Rome. Say ‘Goth’ to a Whig and his heart would quicken, not shrink; it’s no insult, but a rallying cry.

Edmund Burke, contemplating the distinction between the sublime and the beautiful, could have illuminated Vasari’s moment of repulsed awe. His Philosophical Enquiry of 1757 might not have dealt expressly with the Gothic, but by linking aesthetics to metaphysics it had a profound effect on the development of the literary Gothic. To Burke, the beautiful and the sublime were mutually exclusive. The appreciation of a beautiful object inspires ‘sentiments of tenderness and affection’; it is a reasoned aesthetic response, characterised by ‘joy and pleasure’. Conversely, to encounter the sublime is to lose all reason, and all joy. It is instead to experience ‘astonishment — that state of the soul in which the mind is so entirely filled with its object that it cannot entertain any other’. An aesthetic response is effectively impossible, since the sublime is a source of such obliterating light or darkness that the object itself is removed, and we are moved instead to awed astonishment. Burke alludes to the obscurity and gloom of heathen temples, affirming that link between a dark and massy built environment and an encounter with the Gothic. Had Vasari only encountered Burke on the cathedral steps, or if I had met him as I walked dumbfounded through the Forum ruins, he might have offered us both a shrewd diagnosis.

And so to 1762 and the study of Richard Hurd — priest, scholar and fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He will live long, achieve a bishopric, and serve as tutor to the Prince of Wales; but at present he is preoccupied with a vanished age of courtly love and high romantic ideals. His Letters on Chivalry and Romance examine medieval chivalry through the rosy lens of epic poetry, and begins with a startling reversal in the meaning of the Gothic:

The ages, we call barbarous, present us with many a subject for curious speculation. What, for instance, is more remarkable than the Gothic CHIVALRY? or than the spirit of ROMANCE, which took its rise from that singular institution?

Hurd saw the Gothic neither as threatening barbarism nor as a liberal political ideal, but as a vanished (and almost wholly fictitious) epoch of ladies dispensing silk favours to their knights-at-arms. With this one meditation he laid a foundation stone of the Romantic age.

But if ever there was a man to succumb to this most seductive of ailments — a chimera of the barbarous, the sublime, the chivalrous, and the liberal — it was Horace Walpole. He was an 18th-century Whig politician, art historian and belle-lettrist, troubled in matters of faith and of the heart. With Strawberry Hill in Twickenham, his sugar-coated replica of the ‘gloomth’ to be found in the cloisters of a medieval cathedral, he prefigured the Gothic Revival in architecture. Unhappily homosexual, deeply romantic and profoundly committed to liberal ideals, when he wrote The Castle of Otranto (1764) and gave it the subtitle ‘A Gothic Story’, he was claiming the Gothic inheritance in all its guises for the world of literature. Walpole’s novel bears no resemblance to the edifying realism of its contemporaries: it is all villainy, threat, flight, obscurity, and madness. It evokes the sublime and the fantastic. Its cod-Medieval setting was something Hurd would have recognised; it is gleefully suggestive of erotic transgression.

It is this quality of drawing on our own secret urges that makes the Gothic so irresistible

Naturally enough, critics objected to its preposterous narrative and marvellous events. Walpole might have failed by most familiar criteria, but he achieved something altogether more troubling. The defining feature of the literary Gothic is that it exploits the reader’s own devices and desires: it cannot function unless the reader is affected by events as profoundly as any of the characters. Those first readers of Otranto were unlikely to be suffering Count Manfred’s incestuous desires, or cowering like Isabella in crypt and cave. Nevertheless, like Walpole — and like us all — they’d have brought their own secret anxieties and longings to the text. That first encounter with Gothic fiction tested the boundaries of civilised society, hinting at dark places where vices might be explored.

Walpole published his novel at the passing of the Enlightenment age. There can be no doubt that the seductiveness of the sublime — whether encountered in nature, as Burke largely supposed, or within the pages of a Gothic novel such as Walpole’s — thrives most in the aftermath of periods of clarity and reason. The Enlightenment did not dispense with faith but illuminated it, affirming that since a rational God had ordered the universe, order must be found in its workings. The terror of sublimity was a recourse for those who still hungered after strangeness, and after numinous forces that could not be accounted for by the stern light of reason.

In the wake of Otranto, the Gothic spread with remarkable speed, always bringing with it a delightful terror and a roguish testing of accepted behaviour. In The Monk (1796), Matthew Lewis simultaneously revolts and seduces. In Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), the impoverished Irish cleric Charles Maturin invents Gothic horror and satirises the established church. Ann Radcliffe’s tales are sublimely affecting but always shy away from outright supernaturalism. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) plays on post-Darwinian anxieties: where does the man end, and the animal begin?

Sigmund Freud’s essay ‘The Uncanny’ (1919) sits alongside Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry as an essential clue to the meaning of the Gothic. It has never been an aesthetic so much as a state of mind. Freud conceived of the uncanny – an approximation of the untranslatable German unheimlich – as a state of indescribable unease and terror, drawn not from encounters with ghouls and beasts but from something horribly familiar. To be heimlich is to be homely, of the domestic sphere, but also concealed, secret, hidden. What is unheimlich is therefore simultaneously unhomely and revelatory: it spells an unwelcome encounter with our primitive desires and social taboos, an encounter all the more horrible because it is with ourselves.

It is this quality of drawing on our own secret urges that makes the Gothic so irresistible, and accounts for its limitless adaptability. It is defined not by an adherence to a series of defining features, but by our response to it — I am deliciously uneasy, repulsively thrilled, sublimely afraid. It gives licence to sensations that we feel but cannot admit, and at precisely the same time cloaks those sensations in such strangeness that it is possible to say: ‘It is only an absurd tale of vampires and shadows; it has nothing whatever to do with me.’ The Gothic provides a hiding-place and a place of consecration for those seeking what lies beyond the boundary of society and reason, a sublime contagion to which we are never quite immune.