In their memo ‘On the Abolition of the English Department’ from 1968, the lecturers Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (then known as James Ngũgĩ), Henry Owuor-Anyumba and Taban lo Liyong spearheaded an educational revolution at the University of Nairobi in Kenya. Eager to sweep out the vestiges of British colonialism from the university’s English Department, they proposed abolishing it, to be replaced with ‘a Department of African Literature and Languages’. They also suggested a revised curriculum that emphasised the centrality of Africa via the study of its oral and written literature, art and drama.

Building on this manifesto for literary emancipation, Ngũgĩ later drew attention to the immense significance of the written language in his essay collection Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). Here, the Kenyan scholar bid farewell to the English language as his literary medium and vowed to write all future works in Swahili and his native Gĩkũyũ. Instead of espousing colonial languages on the African continent, Ngũgĩ urged fellow African writers to develop literature in their mother tongues.

Snapshots from Ngũgĩ’s career underline the real-life stakes of liberation work. After Kenya gained independence from Britain in 1963, Ngũgĩ worked with Kenyan farmers at the Kamĩrĩĩthũ Community Education and Cultural Centre to create plays that interrogated unchecked political control in their country. Soon after the 1977 performance of Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want, 1977) – a play co-authored with Ngugi wa Mirii, about a crumbling love affair between a poor woman and the son of her wealthy landlord – Kenyan government officials arrested Ngũgĩ. Following his release from prison and protracted exile, he returned to Nairobi and survived a violent assault.

These glimpses into Ngũgĩ’s life lay bare the challenging position in which writers who seek to revamp lopsided archives find themselves. These archives are, to quote Saidiya Hartman in ‘Venus in Two Acts’ (2008), ‘asterisk[s] in the grand narrative of history’, and writers-cum-archivists determine their parameters. Those who are not invested in liberation work may believe that they can produce impartial and authoritative additions to these archives, but it is reckless to presume that writers’ lived experiences do not affect their output. Writers cannot step outside of their historical present any more than they can step outside of their bodies.

Ngũgĩ’s work highlights the benefits of identifying biases and rectifying gaps in imbalanced archives. Nonetheless, there are consequences associated with such initiatives. For instance, while recent scholars such as Donna Zuckerberg and Sarah Bond have received praise for calling to task racist ideologies masquerading as relics of Greco-Roman antiquity, they have also had death threats in response to Zuckerberg’s book on white supremacist receptions of Roman imperial history and Bond’s research on polychromy on ancient Greek sculptures. Such vitriol reminds invested parties that there remains a need for a vast community of thinkers who are willing to apply precision and equity to their research. Only those who examine their convictions to ensure that they are not perpetuating prejudices can help move the needle forward.

For the field of ancient Greek and Roman studies, unchecked subjective biases can all too easily lead to literary colonialism, as is the case in Grace Hadley Beardsley’s The Negro in Greek and Roman Civilization: A Study of the Ethiopian Type (1929). Corrosive ideology has also entered the public sphere, as is apparent in the appropriation of ancient Greek and Roman history by hate groups. Intent on countering these mishandlings of the past, I have elsewhere spoken and written about diverse representations of blackness in Greek antiquity. Continuing to channel Ngũgĩ’s liberation work, I explore ancient portrayals of black people from a variety of locations. The subsequent tracing of blackness in ancient Crete, ancient Nubia and ancient Greece unsettles the hierarchy that tends to emerge in discussions of the past. In particular, the privileging of some histories (read: European) over others (read: African) in the academic and public spheres have unfairly monopolised the parameters of ‘antiquity’.

Geopolitical renderings of blackness that overlay ancient countries onto modern maps with no regard for historical context promote neocolonial narratives. Moving away from these subjective hierarchies, I champion an examination of ancient blackness based on themes, such military might and travel. This approach offers alternative ways of looking at skin colour that does not reproduce the virulent narrative of anti-Black racism. As part of my interrogation of my own historical context, I have also thought carefully about the orthography of blackness I use in this piece. I have adopted a referential practice in which I shift between lowercase ‘black’ and uppercase ‘Black’. Lowercase ‘black’ denotes people with black skin colour and phenotypic features including full lips, curly hair and a broad nose in ancient art, while uppercase ‘Black’ refers to a modern, socially constructed group of people whose melanin is merely one of its distinguishing traits.

One of the earliest known depictions of black people outside of Africa appears on the wall of the ancient royal palace of Knossos in Crete. Under the auspices of King Minos, the legendary ruler of Crete whose name eventually became the label for an entire community, the mythical architect Daedalus is said to have constructed the earliest iteration of Knossos. A 20th-century reconstruction of this palace, which flourished in various forms between 1,700 BCE and 1,400 BCE, features the ‘Captain of the Blacks’ fresco, as it is popularly known, depicting three figures in flight. From left to right, three men run in close succession. They bear almost complete resemblance to each other, except for skin colour and height: the two men in the rear have black skin and are taller than the leader of the trio, who has brown skin. These bare-chested men wear skirts with a striped trim and two bands around each ankle. The shorter man in the scene holds two long, narrow objects in his right hand, and wears a feather in his hair.

The Minoan ‘Captain of the Blacks’ fresco wall art from the House of Frescoes, Knossos Palace, 1350-1300 BCE. Heraklion Archaeological Museum/Alamy

Arthur Evans, the lead excavator at this site (1900-1930), concluded that the fresco depicted a Minoan commander leading ‘Nubian’ (a term I will discuss later) soldiers to fight against Greece. In concordance with his appraisal, I see this scene as a depiction of military might during the Minoan period. I urge you to gaze at this fresco with Minoan viewers – not modern notions of skin colour – in mind. Putting this fresco into its historical context helps to resist the impulse to slap modern conflations of skin colour and violence on this piece. In other words, this expansive view frees ancient blackness from the constraints under which it operates in modernity. By privileging military might over skin colour, we can move towards a more liberatory viewing practice of blackness.

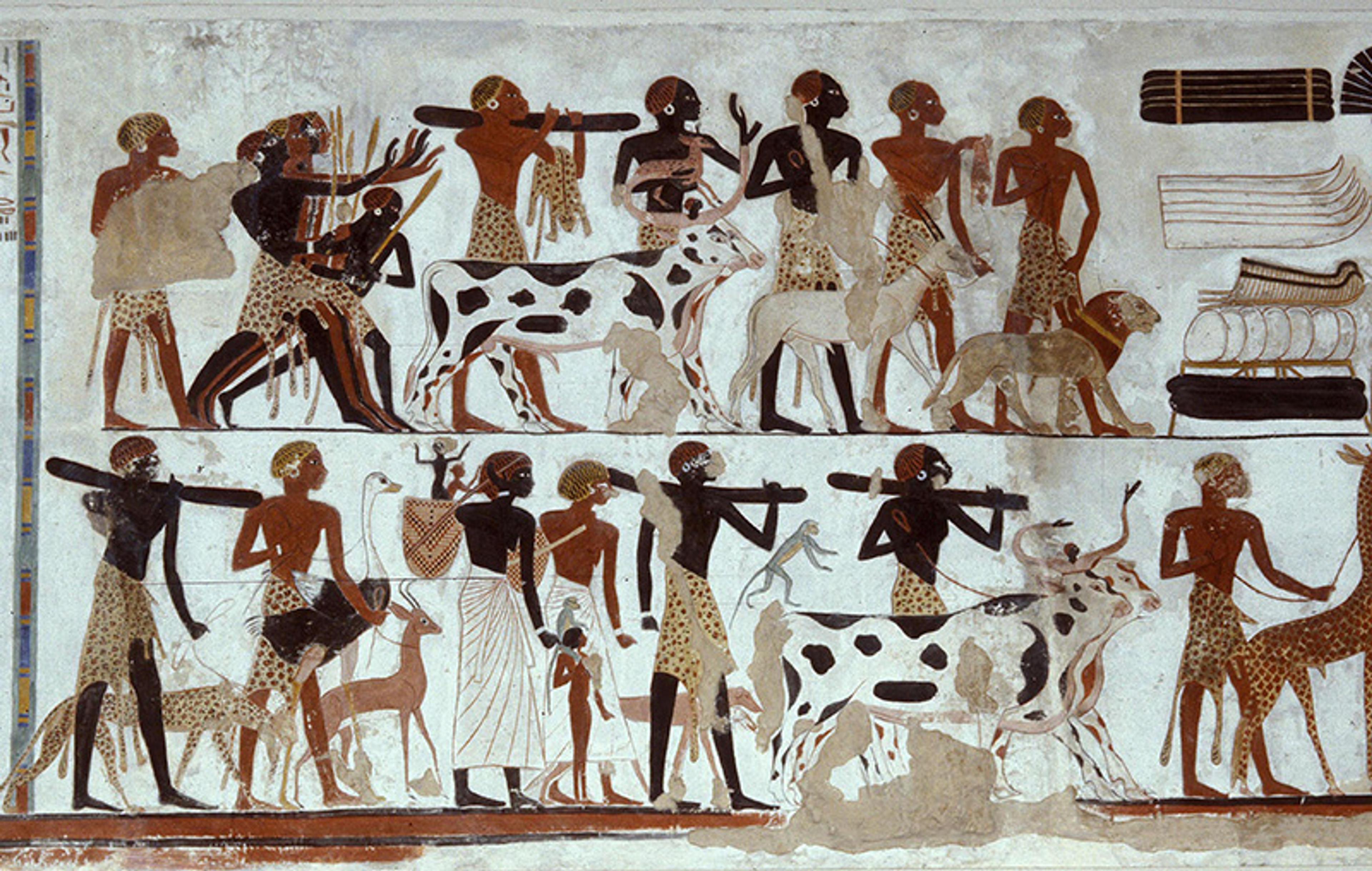

A geographical jump from Crete to Nubia adds to our expansive archive of blackness. The ancient country that spans the southern region of modern Egypt and the northern region of Sudan is known by different names: ‘Nubia’, etymologically linked to the Old Nubian napi (‘gold’) and Middle Egyptian nbw (‘gold’), and ‘Aithiopia’, transliterated from the ancient Greek aithō = ‘I blaze’ and ops = ‘face’, to name a few. A 13th-century BCE frieze painted on the walls at the temple of Beit el-Wali in Nubia (present-day Egypt) depicts two rows of black and brown people. In a reconstructed painting of part of this scene, 18 men walk towards Ramses II, under whose reign the temple was built, with gifts in hand. They lead a retinue of animals, including a giraffe, lion, goat, deer and ostrich; their bounty also includes blunt instruments, pointed spears and a basket with an effigy of a person inside. Eleven men appear on the top half and seven on the bottom, all clad from the waist down in animal or fabric wraparound skirts. Their side profiles reveal their shared features: full lips, curly hair and a hoop earring. In terms of skin colour, some men are black and some are brown. Barring their different shades, there is no clear distinction between the various men in this scene.

Frieze of 18 men with gifts for Ramses II, temple of Beit-el Wali, Nubia. Photo by Alamy

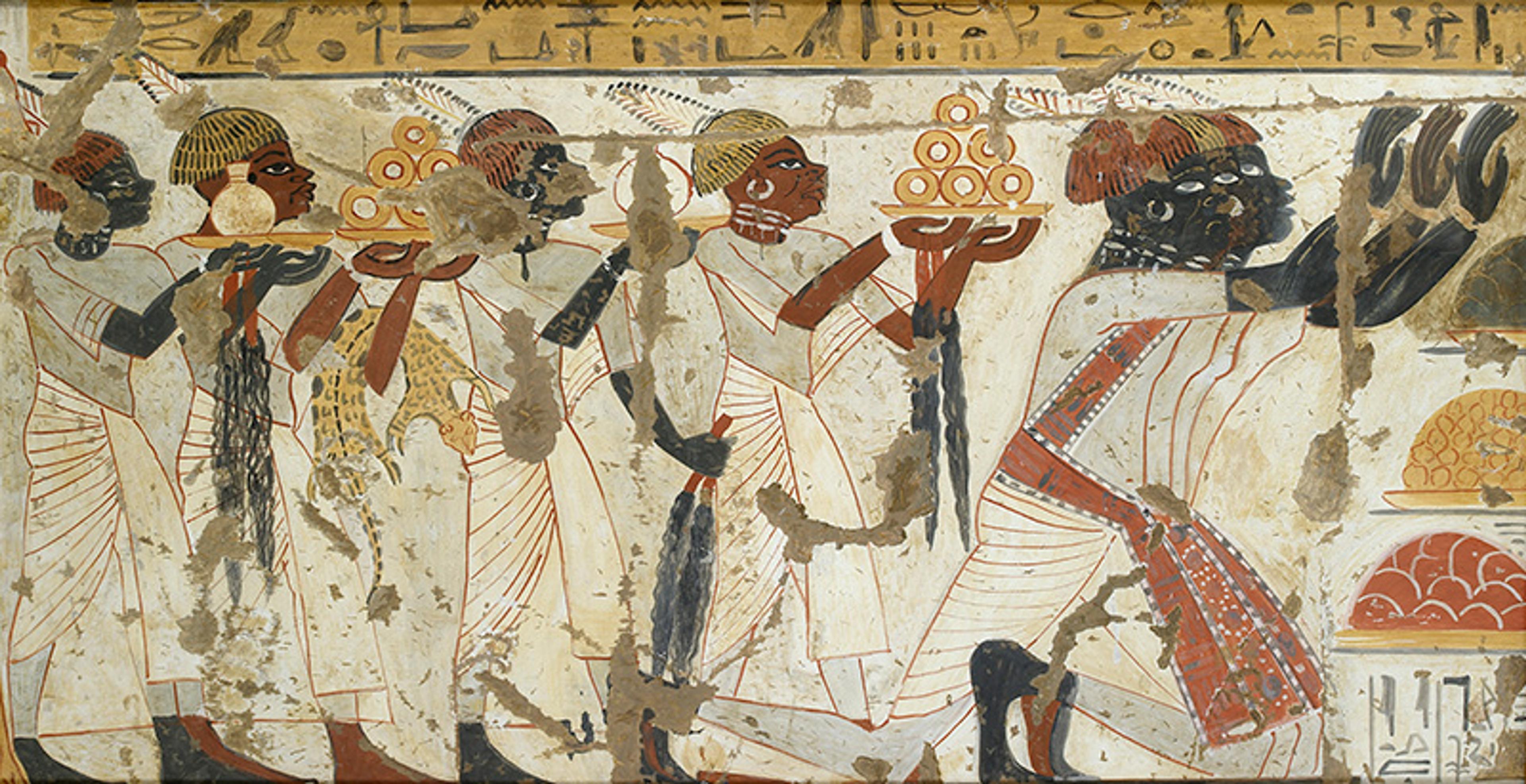

Based on similar imagery elsewhere – such as in the Theban tomb of Huy – that portrays the historically fraught relationship between Nubia and Egypt, it is probable that these black and brown men depict Nubians, people who were embroiled in an ongoing power struggle with their Egyptian neighbours. Despite the contentious relationship between Nubia and Egypt, here the military prowess of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II is on full display. He immortalises his control of Nubia for future generations (even though Nubia regained its sovereignty – and even ruled Egypt in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty). In this vein, Ramses II invites viewers of all time periods to recollect a moment in history when Egypt was the powerhouse in the Nile Valley region. As for the presentation of skin colour, this scene depicts brown and black people as equally indebted to Ramses II. This flexible portrayal of the Nubians’ skin colour suggests that Egyptians did not treat black skin as the Nubians’ sole distinguishing trait. Even so, this wall painting encourages people to view artistic representations of Nubians through a lens that is multicoloured, rather than monochromatic.

Wall painting of Nubians carrying plates, private tomb of Huy, Thebes. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Photo by Getty

Jumping ahead several hundred years, Athens in the 5th century BCE offers numerous portrayals of black people on drinkware used in the symposium. At such lively drinking parties, various Greek inhabitants, including poor men, male immigrants and perhaps women, indulged in boisterous activities. Guests played games and professed their erotic desires, sometimes at the same time. Participants engaged in these lively pursuits, all the while consuming copious amounts of wine. Emboldened by liquid courage, revellers came face to face with representations of black people on their drinkware, including horn-shaped cups (rhyta), wide-mouthed cups (skyphoi), and two-faced (or janiform) high-handled drinking cups (kantharoi).

Skin colour may not have been at the forefront of the ancient revellers’ minds as they drank from these cups

As revellers drank wine from a horn-shaped rhyton depicting a black person engulfed within the jaws of a crocodile, they remained safe from the violent scene at hand. In other words, the horn-shaped cups granted them a sense of security, allowing them to witness black people trying to escape the clutches of reptiles without putting themselves in danger.

Crocodile eating a black man, terracotta rhyton, 350-300 BCE. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

Any attempts to interpret this imagery benefits from readers interrogating their own assumptions regarding skin colour in the 21st century. Without examining one’s historical context, it is all too easy for modern racist ideology to masquerade as historical facts, which in turn can erroneously render black skin colour as inherently brutal. In the context of the symposium, the sight of the violent fate awaiting the black figures on the horn-shaped cups perhaps encouraged drinkers to curb their drinking habits to avoid drowning in wine. Alternatively, a travel warning might have lurked behind this imagery: those revellers who intended to travel across the Mediterranean might find themselves caught in the mouths of a hungry crocodile whose appetite has been whetted by human flesh. In other words, even though skin colour may be the most striking element in this sculpture for a modern audience, it may not have been at the forefront of the ancient revellers’ minds as they drank from these cups.

An implicit call for restraint among wine-guzzling symposiasts also appears in scenes painted on the wide-mouthed skyphoi from the sanctuary of Kabeiroi in Boeotia, in central Greece. At this site, five cups recall a memorable scene from Homer’s ancient Greek epic The Odyssey, in which the nymph Circe coaxes the eponymous hero Odysseus to drink a potion that will transform him into a pig. On one of these late 5th-/early 4th-century BCE cups, both Circe and Odysseus are portrayed as squat, black figures. Barring some fabric draped over his left arm and his brimmed hat, Odysseus is completely disrobed. His erect penis, pronounced nipples and potbelly are on full display. Armed with a sheath in his left hand and a sword in his right, he seems poised to attack Circe.

Circe and Odysseus on a skyphos from the sanctuary of Kabeiroi in Boeotia, Greece. Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Unlike her naked houseguest, the curly haired Circe wears a chiton-like dress. Abandoning the loom behind her, Circe holds a wide-mouthed skyphos in her left hand and a stick in her right with which she mixes a potion. Her modest appearance disguises her powerful talents with which she magically transforms Odysseus’s men into utterly helpless creatures. The contrast between her unassuming looks and her cunning skill mirrors the deceptively powerful role of wine in the symposium. In the event that revellers underestimate this seemingly innocuous drink, the imagery of Circe on these wide-mouthed cups gently cautions drunken symposiasts to pace themselves, lest they transgress acceptable limits of intoxication and end up in dire straits, like Odysseus’s men-turned-pigs. Similar to the horn-shaped rhyta discussed above, skin colour is not the most remarkable element on this wide-mouthed cup.

Remaining in the Athenian symposium, another visual example of blackness circumvents the modern categories of ‘Black’ and ‘White’. A janiform kantharos currently in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum presents two faces. A curly haired black face with full lips and a broad nose appears on one side, and a headband-wearing brown face with thin lips and a narrow nose on the other. The fused clay, most apparent at the neck of the cup, draws attention to the inexorable connection between the two faces. The cup invites multiple versions of difference: viewers may understand the two faces as opposing or complementary.

A janiform or two-faced kantharos, 480-470 BCE, Greece. Courtesy the Princeton University Art Museum

The depiction of two faces fused in one cup cuts across any permanent hierarchy of colour that viewers might be tempted to map onto Greek antiquity. In the minds of modern viewers who are not aware of the ways that cultural conditioning can infiltrate their perspective, there may appear to be an imbalanced presentation of the different faces on these cups. The sharp lines that distinguish each face from the other may mislead them to perceive the cup as a vivid antecedent of 19th-century Jim Crow segregation laws in the United States. Despite some people’s tendencies to draw these short-sighted conclusions, it is worth emphasising that there is no simple colour binary at play here. To be sure, colour was part of a larger apparatus of distinction on ancient Greek pottery, but its valence was not perpetually fixed. Close scrutiny of portrayals of black people in their historical context helps to dismantle the troubling assumptions that this ancient blackness operates in the wake of the transatlantic slave trade. Simply put, ancient Greek representations of black people demand more robust interpretations than the inaccurate ‘blackness = inferiority’ trope that European enslavers generated to justify the violence they meted out to fellow humans.

Mindful of the gap between renditions of black people in antiquity and the lived experience of Black people in modernity, I turn to poetry as a closing example of a revamped archive. In the poem ‘To Those of My Sisters Who Kept Their Naturals’ (1980), Gwendolyn Brooks provides a blueprint for unearthing silences. In this ode to Black women and their unprocessed hair, the Black female narrator turns away from the society in which the disrespect for Black women runs rampant, and she aims to free Black women from any doubts of their intrinsic worth. Under her careful tutelage, readers are primed to look beyond predetermined parameters to access performances of liberation. In her words:

To Those of My Sisters Who Kept Their Naturals

Never to look

a hot comb in the teeth

Sisters!

I love you.

Because you love you.

Because you are erect.

Because you are also bent.

In season, stern, kind.

Crisp, soft – in season.

And you withhold.

And you extend.

And you Step out.

And you go back.

And you extend again.

Resisting societal pressure to hail the hot comb, the narrator develops an inclusive project of hair politics. The punctuation undergirds the shared sisterhood in this undertaking. First, the narrator’s opening exclamation (‘Sisters!’) demands that her intended listeners heed her call. The succinct sentence that follows (‘I love you.’) encapsulates the narrator’s message of adoration. The period at the end of each ensuing clause allows each of the sisters’ loving qualities to stand on its own, while the repeated conjunctions (‘because … and’) situate each clause as part of a collective unit. In addition to the camaraderie undergirding the poem’s opening lines, the text’s visual presentation lends itself to comparison with a single strand of curly hair. Readers who turn their head to the side when reading the entire poem will notice that it resembles an undulating curl pattern. From this angle, each staccato phrase contributes to the long curlicue of hair.

The narrator uses hair as a vehicle through which she praises the resilience of Black women. Her oscillating observations enumerate the positive qualities of Black women via their hair: straight or curly, harsh or gentle, rigid or pliable, all are worthy of her love. Her embrace of passive and active vocabulary (‘you are also bent’, ‘you Step out’) further demonstrates the versatility of her subjects. Despite the unnamed forces that have bent them, they insist on forging ahead. Moreover, the narrator’s repetition of verbs of movement (‘you Step out … you go back’) counteracts the immobility that has driven some women to ‘look a hot comb in the teeth’. The narrator’s message of solidarity encourages her sisters to embark on a restorative journey toward their own liberation.

Brooks’s poetic reorientations of Black identity offer a creative way to approach silences in the archives. In concert with Ngũgĩ’s appeal in 1986 for literature written in African languages, Brooks demands that readers make space for the voices of Black people. In this vein, I have carved out some space for multidimensional representations of blackness in antiquity. It is my hope that, in the future, people examine their convictions and context to ensure that they are not perpetuating silences or prejudices. The task ahead is a challenging one. Opening up reductive presumptions, teasing apart overlapping representations – not to mention addressing voices that are missing from the archive – requires committed confrontation. Nonetheless, it is only with vigorous and persistent revising of static presumptions across disciplines that we can equitably untangle the archive of blackness.