At the dawn of the 20th century, Italian patriots were struggling to overcome a profound inferiority complex. Ever since 1861, when Giuseppe Garibaldi unified the country’s disparate regions into a nation-state, politicians and intellectuals had been anticipating the arrival of a glorious new era. Decades on, however, the economic, diplomatic and cultural results were wanting. Nationalists knew they needed a new mythos to boost public confidence, something to make Italy seem strong and competitive on the world stage. Several options were on the table. Some saw religion as a source of potential unity. Others pointed to the Renaissance, and the long tradition of democratic republicanism as admirable blueprints. After much debate, however, most statesmen came to settle on ancient Rome. The classical legacy, so they reasoned, while admittedly rather distant, was a moment when the peninsula had been at the centre of European and, arguably, world affairs. They set out, quite consciously, with this history in mind, to tell their fellow citizens a new story: that they would make Italy great again.

What this meant in concrete terms was imperialism. In 1912, to demonstrate its global aspirations, Italy launched a ferocious attack against Ottoman Libya. As the bombs fell over Janzur, the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio wrote the ‘Songs of Our Exploits Overseas’, in which he conjured up the spirit of Vittoria, the Roman goddess, to call on all patriots to re-connect with the ‘eternal memory’ of the ancient past, and overcome the stifling ‘crust of centuries’ in order to set out again, under a new flag, to dominate the world. Other nationalists followed suit. The essayist Alfredo Oriani’s 1889 tract describing the need for the country to ‘sail once more on its sea’ as the ‘bringer of a new civilisation’ was republished in 1912, while the journalist Enrico Corradini went as far as to suggest that there was a hidden Roman road concealed under the Mediterranean Sea that linked the modern Italian nation to the African colonies over which it had a ‘historic claim’. Notably, all of these writers referred to the water by its ancient Roman name, Mare Nostrum (‘Our Sea’).

Like all modern colonialism, Italy’s propagandising had racist overtones. In fact, one of the main reasons that the country’s intellectuals were so anxious to present themselves as a homogeneous group was, ironically, a byproduct of their nation’s Mediterranean geography. Over generations, people from both sides of the sea, from Tangier to Istanbul, had mixed with one another to the point that the Italian peninsula’s inhabitants couldn’t feel certain of their ethnic ‘purity’. In response, in the 1920s, philosophers such as Julius Evola posited esoteric theories about an Aryan ‘super-race’, a kind of spiritual nobility that had apparently always existed in Italy since Roman times, and which gave the ‘true’ Italians the moral right to dominate non-Europeans. These strands of thought combined in the ideology of fascism.

When Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922, he did so wielding Roman imagery – the eagle, the fasci and a fictitious ‘ancient’ salute – even more aggressively than D’Annunzio and his forbearers had. At the same time, Mussolini opportunistically supported the burgeoning field of race science, encouraging anthropologists and eugenicists such as Alfredo Niceforo and Sabato Visco to produce ‘empirical’ evidence for what he called the ‘innate vitality’ of the Italian race.

In 1934, Italy’s fascist regime commissioned an installation to visualise their destiny as the righteous inheritors of a white Roman empire. The work, which was realised by the architect Antonio Muñoz, was comprised of five maps that were displayed along the exterior walls of the ancient Basilica di Massenzio in Rome. Four showed Roman civilisation at different stages of its evolution, from the age of Romulus to that of Trajan. The final image, however, which Muñoz completed during Italy’s campaigns in Ethiopia in 1936, depicted Mussolini’s own plan, to obtain control over the entirety of East Africa. This wasn’t all. Muñoz also designed his maps according to an anachronistic and ideologically charged colour scheme, rooted in ‘race science’. Everything inside the ‘Italian’ world – in both the ancient and modern images – was designated by white travertine marble. Everything beyond it was black.

Muñoz’s maps of Italy’s imperial imagination, displayed on the Basilica di Massenzio in Rome. Creative Commons Licence

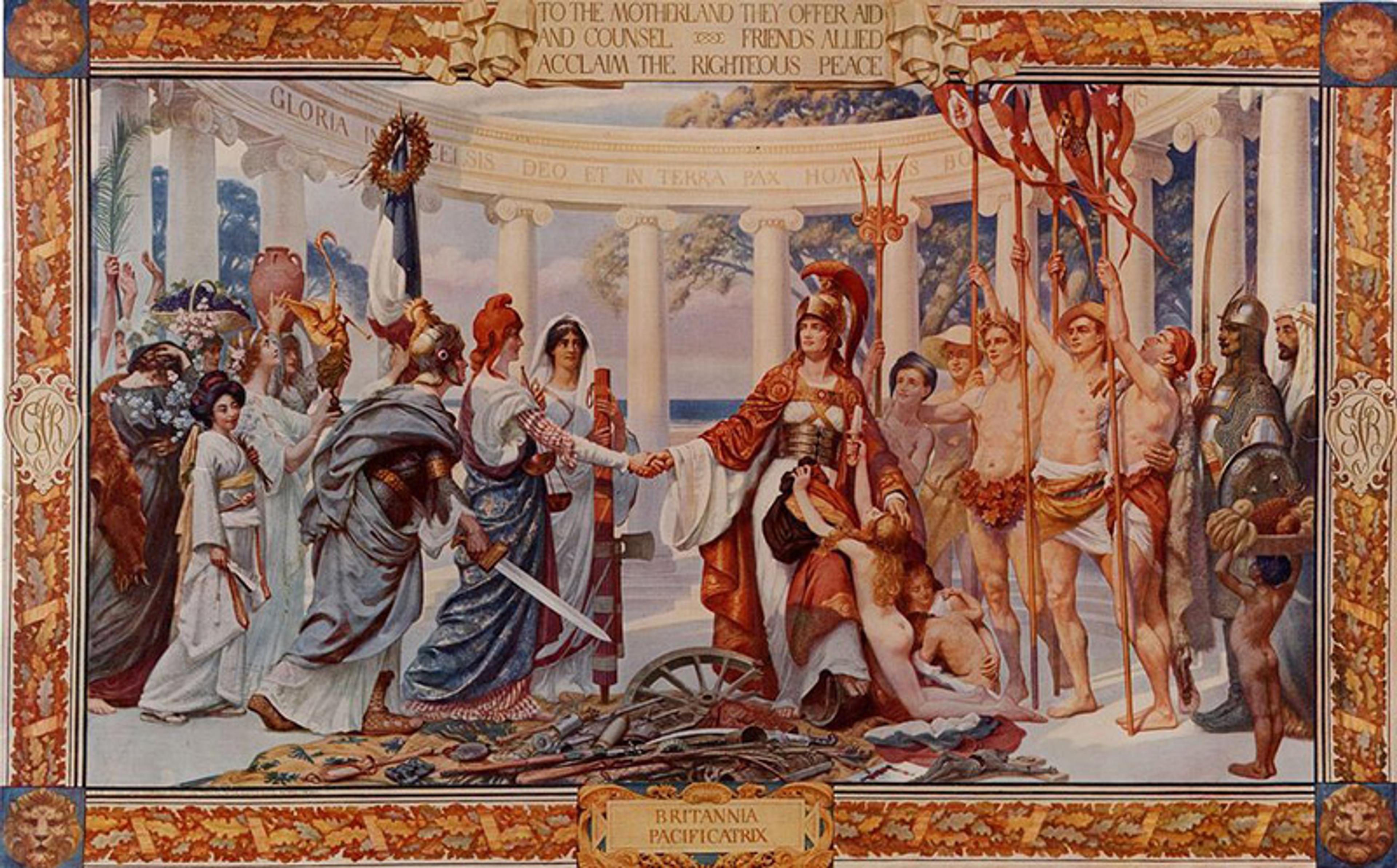

Today, it’s tempting to disregard Mussolini’s use of classical antiquity as a minor quirk of Italian fascism. The uncomfortable truth, however, is that all the major European powers have drawn comparisons of a similar sort that leaned on ancient Rome. Britain, for example, which led the opposition to Axis forces in the Second World War, had long appealed to this kind of symbolism to justify its own imperial expansion. In the 19th century, intellectuals across the political spectrum, including Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Curzon, Arthur Balfour and Rudyard Kipling, all cited Rome as a moral justification for British incursions in India, on the basis that they, the white Europeans, were, as they thought, ‘bringing civilisation’ to the brown and Black natives. In London in 1912, the painter Sigismund Goetze began a series of D’Annunzio-esque murals for the Foreign Office, in which he invented his own white fantasy of Roman antiquity. Like the fascists, Goetze used Latin and neoclassical figures to celebrate his country’s victories over various nonwhite peoples. One image, which professes to show God’s kingdom on Earth, is particularly disturbing. At the centre we see Britannia, clad in her Roman imperial armour. She is surrounded by an array of highly stereotyped devotees, including a Japanese geisha and a Persian warrior. Africa, meanwhile, is depicted at the very bottom of the racial hierarchy, as a naked servant boy, carrying fruit on his shoulders

Britannia Pacificatrix by Goetze (1921). Photo courtesy the FCO

The myth of a white Rome is so embedded in the Western imagination that it has even found advocates outside Europe. It’s well known that the founding fathers of the United States held the ancient republic in high esteem. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were great admirers of Cicero, whom they saw as a defender of justice, while Alexander Hamilton and Patrick Henry identified Cato the Younger as the incarnation of liberty.

Their idealism, though, can’t be disentangled from the realities of racism and slavery on which the US was actually built. Indeed, it’s hardly surprising, given the rhetorical efforts to disguise such unpalatable realities, that anti-abolitionists would later turn to Rome to justify white supremacism. In 1852, Thomas Roderick Dew, a well-respected professor from Virginia, argued that ancient Rome, where ‘the spirit of liberty glowed with the most intensity’, was able to do so only because ‘slaves were more numerous than the freemen’. In 1916, following emancipation, the lawyer and zoologist Madison Grant tried to exploit the fears of many white Americans by appealing to a story of Black people ‘breeding out their masters … [as] in the declining days of the Roman Republic’.

Most of us would, I hope, oppose this kind of racist discourse on moral grounds. Yet it’s important to recognise that, while there are big differences between Italian fascism, British colonialism and pro-slavery groups in the US, all have contributed to a fantasy idea about Rome’s whiteness that’s still a feature of Western civilisation. Of course, a diverse cast of high-profile figures in these countries, from Antonio Gramsci to Franklin D Roosevelt, have, in different ways, worked to rebuff this abuse of history. Here, however, I want to focus on two lesser-known arguments that are particularly relevant for our own postcolonial times: firstly, that the Romans didn’t have a sense of race in the modern sense of that word. Secondly, and just as importantly, that their empire, unlike modern equivalents, was one in which people we’d now consider nonwhite played a leading role.

Before turning to the ancient world, it’s important to confront any lingering suspicions that race is a legitimate scientific concept. This shouldn’t be contentious. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the vast majority of human genetic alleles are shared across the entire species, and that, even among groups we habitually call ‘races’, variation is too great to identify distinctive, stable categories. The consensus on this matter is now so great that Craig Venter himself, the pioneer of DNA sequencing, has stated that ‘the concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis’.

This caveat aside, my main interest here is not the biology of race but how we imagine race though narratives of whiteness. White skin is a neutral physical trait. The idea of whiteness, however, has strong cultural connotations. Postcolonial theorists, inspired by the seminal work of Frantz Fanon and Edward Said, now agree that European powers invented this concept during the Enlightenment as a pseudoscientific justification for their political expansion. Whiteness was, as these figures demonstrated, both an explanation for and a condition of European supremacy. This normative system, which inequitably required a Black other to inhabit all corresponding inferior concepts, is the basis on which modern racism thrives today.

There is a case to be made that the Romans, through the Latin language, were the progenitors of Western culture. As members of an ancient Mediterranean society, however, they didn’t have any notion of whiteness. One straightforward reason for this is that they weren’t, or weren’t primarily, what we’d now term white. In the past, such discussions were largely speculative. Today, though, thanks to research from Stanford University published in 2019, we have a full genetic history of Rome showing that, in the 1st century CE, the city-state was populated by many peoples of Near Eastern and North African descent. So the fascist idea that ‘it is a mere legend that large masses of migrants came into [Italy]’ – as the authors of the country’s ‘Race Manifesto’ argued in 1938 – has now been proven wrong definitively.

Archaeological and literary sources add further nuance to this picture. Virgil himself, of course, wrote in his Aeneid that Rome’s founding fathers weren’t Europeans but Trojans, a mix of Anatolians and other Asian and Middle Eastern peoples who crossed sea to create a new cosmopolis. Meanwhile, the remains of houses, temples and other artefacts in Sicily and southern Italy clearly show that Asian Greeks and Middle Eastern Phoenicians were integrating with Italic tribes as early as the 7th century BCE.

Some scholars have suggested that the Romans didn’t have any concept of race as a category. This isn’t quite correct. They actually had several words, including ethnos, genos and natio, by which they distinguished peoples according to familial lineage, and which, at times, overlapped with race. Their main organising principle, however, was geographic. The Romans divided the tribes of modern-day France and Germany into groups including the Belgae, Aquitani and Celtic Gauls; and they distinguished these groups in turn from the Spanish Iberians and Gallaecians. As far as Africa is concerned, they carved up the continent to establish distinctions between Egyptians, Algerian Berbers, whom they called mauri, and the ‘Punic’ Phoenicians.

Almost all white marble works were originally painted in polychrome blues, reds and yellows

One term that does present some issues is aethiops. Originally, the Romans used the word to refer to a particular tribe: the Kush peoples of Nubia. Over time, however, writers came to use it rather generically to refer to all peoples from Sub-Saharan Africa. Unusually for a Latin ethnic distinction, the word itself, which has its etymological origin in the Greek for ‘burntfaced’, does seem to evoke physical appearance. In practice, however, this isn’t how Romans used it. When they did need to describe dark skin as a physical property, they turned to other concepts, such as melas, ater and fuscus – terms used to describe individual people. Aethiops was a geographical and value-neutral term that, just like Gauls, referred to cultures with origins south of the imperial frontiers in Tunisia and Libya.

Roman writers were certainly guilty of what we’d now call ‘racialism’, which is to say they speculated that certain cultures of certain areas exhibited certain behavioural traits. A lot of this was tied to their ideas about the weather. Vitruvius, for example, notes that Africans were healthy and intelligent, but that the sun had dried up their blood which, he thought, made them cowardly. He describes the Germans, by contrast, as being stupid people, but who, having had to deal with cold weather, were strong, with a healthy blood flow. Crucially, there’s no hierarchy here in which ‘white people’ might be seen as being ‘above’ Black people: while Juvenal warns that Africans are cannibals and criminals, Seneca celebrates them as being naturally freedom-loving which, in his own personal schema, is a virtue. It’s important to note that these were subjective remarks. There is no evidence that Roman institutions made any attempt to develop either of these positive and negative judgments into a system, let alone a science with a claim to objectivity. In fact, even the most bigoted writers fell short of extrapolating from whiteness as a signifier of supremacy. Juvenal might have despised Africans, but he also reserved a disgust for the Germanic tribes, whom he considered degenerate and unnatural in part on account of their pale skin and blue eyes.

Many people, wittingly or otherwise, have failed to grasp the importance of these distinctions. In the 18th century, the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann identified ‘The Apollo Belvedere’, a 2nd-century sculpture, as a paradigm of classical beauty, something he attributed at least in part to its whiteness. Like others to this day, he made the mistake of assuming that the abundance of plain marble statues that remain from antiquity are evidence that Roman populations preferred white bodies to Black ones. This is wrong for many reasons. Firstly, because there are plenty of examples of statues that were made from grey, pink and green marble. More importantly, though, because literary sources tell us that almost all such works were originally painted in polychrome blues, reds and yellows.

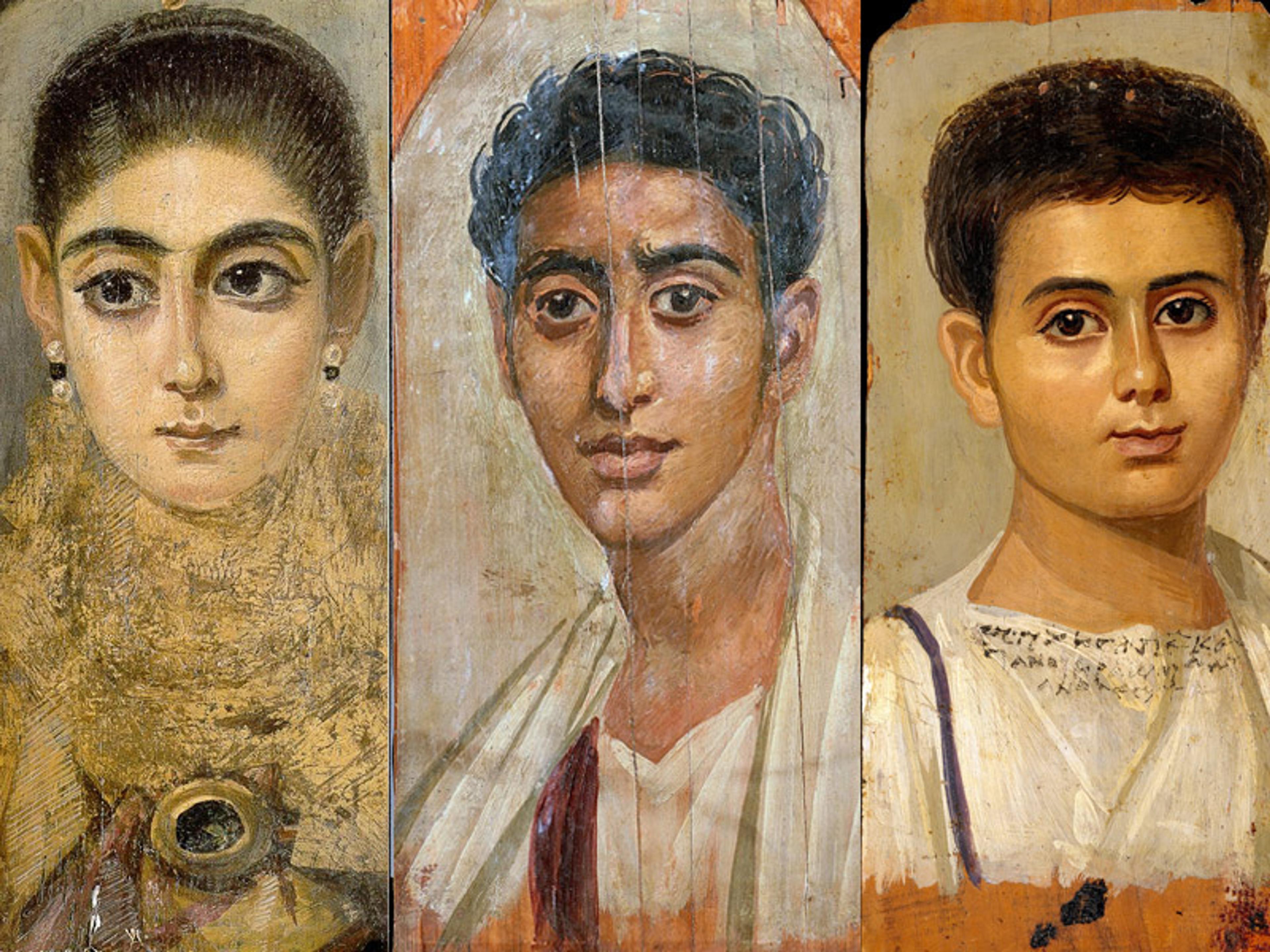

Some particularly obstinate critics have responded to this by arguing that most statues nevertheless demonstrate a ‘European physiognomy’. Leaving aside the question of what this might actually mean, we can see from other artforms, such as paintings, that Roman ideas of beauty weren’t exclusively white. The Fayum portraits, from the 1st to 3rd centuries, depict brown-skinned, dark-eyed people in a manner that clearly suggests them worthy of admiration. Poets too have left numerous odes celebrating Black bodies: Asclepiades, an Asian physician, likens the object of his desire to a ‘coal’ that, when heated, comes to ‘glow like rosebuds’, and Martial describes a woman who is ‘darker than night, than an ant, pitch, a jackdaw, a cicada’ as an ideal of beauty.

The Fayum portraits, from the 1st to 3rd centuries. Photo montage courtesy Wikipedia

There might be no evidence to suggest that African Romans experienced any serious discrimination based on their skin colour. Nevertheless, much like the English and Germans, these people did struggle to overcome their reputation among Romans for being ‘provincial’. While Rome’s imperial elite was multiethnic, the ruling class was dominated by patrician families who claimed ancestry to the founding nobility. This made it difficult for citizens born in more distant territories to rise through the ranks. It wasn’t, however, impossible. In fact, there are plenty of examples of nonwhite individuals achieving respectable positions. One of the most common ways of doing so was through a military career. Lusius Quietus, a cavalry commander, born in modern-day Morocco, obtained such prestige on the battlefield that Trajan actually named him as his successor to be emperor (unfortunately for Quietus, though, he was assassinated in 118 CE and thus unable to take up the position). Maris Ibn Qasith, a dashing soldier from Asia Minor, became a celebrity following his successes in fighting the Gauls.

Literature and philosophy provided an alternative path for success. Terence, who was from modern-day Tunisia, authored several popular comedies that in later centuries would influence such European luminaries as William Shakespeare and Molière. Apuleius, from modern-day M’Daourouch in Algeria, authored the only surviving Roman novel, The Golden Ass. Marcus Cornelius Fronto, an orator and grammarian, was of Berber origins, though he clearly encountered no obstacles that prevented him being selected to tutor two future emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Not even Caracalla’s most vocal critics forwarded objections based on the emperor’s skin colour

The rise of Septimius Severus is perhaps the most clear-cut example of someone we’d now call a ‘Black Roman’ reaching the top levels of the establishment. Born in 145 CE in Leptis Magna, in what is now Libya, Septimius moved to the capital in his teens and worked his way slowly through the political ranks, attacking corruption in the senate as he went. In 193 CE, having secured considerable public support, he launched a successful military coup and took power as emperor. However, what’s most interesting about Septimius, for our purposes, is how he both downplayed and celebrated his African identity. On the one hand, the emperor was anxious not to appear provincial. He worked hard to disguise his Punic accent, and made a concerted effort to travel to the extreme north, as far as Scotland, to demonstrate his worldliness. At same time, Septimius was clearly proud of his roots. His closest advisor, Plautianus, was a friend from Libya, and he established a new imperial corps, filled with Punic soldiers, to replace the Praetorian Guard in Italy. Septimius invested large sums of money in Leptis Magna throughout his reign and commissioned both a triumphal arch and a sizeable forum for the city. By the end of the 2nd century, his once unremarkable hometown was, along with Alexandria, one of the wealthiest metropolises in the empire.

The most remarkable aspect of the Severan story, though, is not so much Septimius’s individual achievements as what his dynasty tells us about politics of race in the empire. Septimius’s elder son Caracalla was, by most accounts, a poor, vengeful and intemperate ruler. Nevertheless, it was he who in 212 CE passed one of the most ‘progressive’ works of Roman legislation, the Antonine Constitution, which declared that all free peoples residing within imperial territories were entitled to full citizenship.

Historians have often sought to downplay the importance of this measure, arguing that Caracalla introduced the policy only to increase tax revenues for his own benefit. His personal motivations, though, are hardly relevant here. The fact remains that in the 3rd century, a fledgling, peripheral dynasty successfully united all peoples from Germany to Syria into the same body politic. Caracalla’s contemporaries attacked the emperor for his decadence, his narcissism, his superstition and his bloodthirstiness. Not even his most vocal critics, however, such as the historian Cassius Dio, forwarded objections based on skin colour. We can’t ignore this silence. Indeed, it arguably tells us as much about the Romans’ attitudes to race as the few fragmented chronicles that do remain.

It’s not difficult to see why modern colonial powers turned to Rome for inspiration. The republic and empire were both patriarchal societies that, at times, condoned military expansionism. And although they were cosmopolitan in a sense, they were also xenophobic, and intolerant of other cultures that proposed to govern according to their own rules. However, as I’ve shown, the idea that Rome has ever been white is unsustainable on just about every count. Unfortunately, to this day, this hasn’t stopped far-Right groups from reproducing a distorted and racist version of the classical past for their own benefit. In 2016, members of Identity Evropa (later called the American Identity Movement), a now-disbanded neo-Nazi organisation, began deploying classical statues as avatars in their forums. This trope has since become a hallmark of white supremacist communities.

Meanwhile, Richard Spencer, the US conspiracy theorist, has openly called for the formation of a new ‘ethno state’ that would, he claims (contrary to all historical truth), represent a ‘reconstitution of the Roman empire’. His supporters include members of the chauvinist group the ‘Proud Boys’, and the incels once associated with the Reddit forum called the Red Pill and who are now producing ‘classical’ gifs, in which they attribute fictional ‘racist’ quotes to ancient writers in order to ‘own the Libs’ on Twitter and Facebook. There’s nothing trivial about this phenomenon. As the classicist Donna Zuckerberg warned in 2018, these groups aren’t just joking around: they’re ‘[turning] the ancient world into a meme’ in order to project their ideology into the world.

It might be reasonable to simply ignore this propaganda if it wasn’t increasingly visible offline too. In 2017, when far-Right activists marched in Charlottesville, they did so behind images of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, over which they superimposed phrases such as ‘Protect Your Heritage’ and ‘Every Month Is White History Month’. Several of the rioters who stormed the Capitol building in Washington, DC earlier this year were wearing T-shirts with Rome’s golden aquila, as well as tattoos of the letters SPQR, the motto of the ancient Republic. One demonstrator even attended the rally with a placard in which Donald Trump’s face had been Photoshopped over of the face of Maximus Decimus Meridius, the fictional hero of the film Gladiator (2000), above the message ‘Cross the Rubicon’ (a reference to the moment when Julius Caesar ascended to the role of dictator).

How many TV shows are produced each year about the Celts and Gauls, how few about Berbers and Aethiops?

The Washington, DC rioters planned their insurrection to contest what they saw, falsely, as a ‘rigged’ presidential election. Yet their actions had a symbolic meaning too that’s inseparable from uncomfortable truths about US history. The organisers were clearly aware that the Roman iconography of the Capitol building, which was built by enslaved people, does indeed represent a fraught duality of democracy, on the one hand, and racism on the other. By ‘occupying’ the space in such a bizarre theatrical fashion, and sharing selfies among the Corinthian columns, they were eking out the unresolved contradictions still present at the heart of the institutions themselves. By re-animating a US version of the white-Rome fantasy, they were, like many before them, providing an anachronistic justification for racism.

Since the 1980s, and the publication of Martin Bernal’s seminal three-volume history Black Athena (1987-2006), classicists have been trying to decolonise their discipline to prevent misappropriations of just this sort. Today, there’s a new urgency to this discussion. In 2015, Zuckerberg founded Eidolon, an online, open-access journal that aims to provide a platform for ‘Classics without fragility’, and, by extension, better educate the public on the nuances of how ancient peoples actually approached subjects including race. In 2017, in a similar vein, a coalition of scholars set up Pharos, a web project that’s working to counteract the far-Right distortion of the past by ‘documenting and responding to appropriations of Greco-Roman antiquity’ in the form of a fact-checking database. It’s clear, however, that serious changes are still needed within the academy itself. In 2019, during a meeting in San Diego of the Society of Classical Studies, Dan-el Padilla Peralta, a Classics scholar at Princeton University, was publicly accused by a white classicist of having reached his position thanks only to his skin colour. Peralta responded provocatively, stating that if Classics doesn’t prioritise diversity immediately, it will never confront its own complicity in constructing the ideology of whiteness and, as such, the field should be dissolved for the good of humanity.

Inevitably, the discussion about how to actually improve representation, and so transform the canon, will have to take place in universities. Those of us watching from the outside, though, need look no further than our TV screens to see where else things might usefully change. Think, for example, of how white our cinematic ideas of Rome are. How many films have been made that explore the assassination of an improbably Caucasian Julius Caesar? And how few engage with the realities of life in, say, Leptis Magna? How many narratives are produced each year about the Celts and Gauls, and how few about ancient Berbers and Aethiops?

Thankfully, over the past two decades, increasing numbers of artists have been working to address this imbalance, and some have even taken up the invitation to ‘rediscover’ Rome’s forgotten cosmopolitan frontiers. Bernardine Evaristo’s novel The Emperor’s Babe (2001), which follows a young girl from Sudan who has an affair with Septimius Severus in ancient Londinium, is an exciting and energetic work of fiction. By conjuring up the Black voices of imperial Rome, however, it’s also a political text that challenges readers to rethink their assumptions about ancient societies. Beya Gille Gacha’s Venus Nigra (2017), a black bust of the classical Roman love goddess, is a beautiful and enigmatic work in its own right. Like Evaristo’s novel, though, it too serves a didactic purpose, in this case to educate the public about the racist appropriation of white marble statues.

The significance of Rome changes with every generation, and ours is no exception. Yet there is an opportunity here, as well as a threat. While classicists face the urgent question of how to redeem their discipline from colonial bias, cultural practitioners have an unprecedented chance to help the wider public engage with an idea of Rome that’s more diverse, realistic and interesting than the monochrome fantasy that has dominated our recent past. As white supremacists storm the centres of Western governance, this is not just a niche issue. It could play a vital role in strengthening our democracies.