Twelve-year-old Gwenyth has dark brown eyes and a fierce desire to change people’s negative perception of sharks. She attends West Oaks French Immersion school in Ontario, where she and about a dozen other kids who test as gifted, spend three days every other month exploring topics outside their usual curriculum. Most recently, they studied forensics, searching for clues, avoiding red herrings, and learning how scientists test for DNA evidence.

But it’s sharks that fascinate her. She’s determined to be a marine biologist some day and has given considerable thought to what she’ll need to achieve this. Her teacher, Mrs Ensing, who is optimistic about Gwenyth’s prospects, routinely tells her elite group that they can be anything they want to be.

Gwenyth likes her teacher but is troubled by this philosophy. ‘You can’t be anything,’ she says, ‘if you don’t manage to get the marks good enough, or if you have the wrong idea about it. There was a guy on YouTube who wanted to be a veterinarian and they made him watch a video of something happening to an animal and he fainted, so he didn’t get the job.’

Her skepticism is well-founded. A 2012 LinkedIn survey showed that roughly one in three adults are working at their ‘dream job’, which means that two in three are not. Gallup’s most recent State of the American Workplace poll came up with similar results when it concluded that 30 per cent of employees are ‘engaged’ in their work, while 52 per cent are ‘not engaged’ and 18 per cent are ‘actively disengaged’.

‘When you tell somebody: You can be anything,’ says Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of Generation Me (2014), ‘that “anything” they’re thinking of is rarely a plumber or an accountant.’

Indeed, a 2011 survey of more than 5,000 children around the world revealed that while almost half of children in developing countries dreamed of becoming doctors and teachers, more than a quarter of American children aspire to such careers as professional athletes, singers and actors. When a grown‑up asks the inevitable: What do you want to be when you grow up?, most kids have an answer: video‑game developer; astronaut; back-up dancer for Rihanna. And many grown-ups will congratulate them for dreaming big, assuring them that, with hard work and a can-do attitude, they can be anything they want.

When your child is four or five, barring intellectual disabilities or severe behavioural diagnoses, anything does seem possible. A child shows an interest in art and we imagine his work eventually hanging in galleries. A talented runner, we think, might make the Olympics. Kids who love science are given microscopes and we begin to wonder if we should start saving up for college fees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Backing our hopes and theirs are the culture’s cheerleaders, led by viral convocation speeches and a steady stream of ‘overnight’ successes unveiled on reality shows and YouTube, all urging us to dream big and never give up.

Consider Steve Jobs’s commencement address to Stanford graduates in 2005. He was, of course, talking to the high achievers who had already earned a degree from a prestigious university. But with more than 22 million views on YouTube, his advice – ‘find what you love… Don’t settle’ – has resonated with the masses. Oprah Winfrey, whose own rags-to-riches tale gives her moral authority, insists that if we follow our passion, achievement will follow. Even Dr Seuss left us with Oh, the Places You’ll Go! (1990), which has become the go-to graduation gift for millions, assuring kids that their imminent success is ‘98 and ¾ per cent guaranteed’.

As long ago as the fourth century BCE, the Greek philosopher Aristotle celebrated the value of a meaningful goal when he coined the term eudaimonia (‘human flourishing’). The concept re‑emerged in the 16th-century Protestant concept of a ‘calling’. More recently, in the 1960s, a whole generation of young people brought up at the height of an economic boom began asking whether work could amount to more than just paying the bills. Couldn’t it have something to do with meaning and life, talents and passions?

It was then that the episcopal clergyman Richard Bolles in California noticed people grappling with how to choose that special, meaningful career, and responded by publishing What Color is Your Parachute? (1970), which has sold more than 10 million copies, encouraging job‑hunters and career-changers to inventory their skills and talents. Bolles bristles at the suggestion that he’s telling people to be ‘anything’ they want to be. ‘I hate the phrase,’ he says. ‘We need to say to people: Go for your dreams. Figure out what it is you most like to do, and then let’s talk about how realistically you can find some of that, or most of that, but maybe not all of that.’

But in this culture of entitlement, gratification and intensive hyper-parenting, Bolles’s cautionary note has barely made a dent. At Florida State University, the sociologist John Reynolds reported that the gap between goals and actual achievements grew significantly over the period from 1976 to 2000. His study, published in Social Problems in 2006, found that just 26 per cent of high‑school seniors in 1976 planned to get an advanced degree and 41 per cent planned to work as professionals, compared with 50 per cent and 63 per cent, respectively, in 2000. Despite the soaring change in ambition, there was no increase in advanced degrees. What did increase was disappointment; the gap between expectation of earning an advanced degree and actually getting one grew from 22 percentage points in 1976 to 41 percentage points in 2000.

Having lofty dreams can be a wonderful thing. It’s a natural part of childhood to imagine great things for ourselves, says Laura Berk, a professor emerita of economics at Illinois State University and one of the world’s experts on play. And, as kids grow and try, and succeed and fail, the world will shape those dreams.

Behind the bromides is the wish that we not be bound by our talents, by our genetics, by our temperament, by our character

The problem arises when we counter the world’s feedback with platitudes such as ‘you can be anything you want’ or ‘don’t give up.’ Tracey Cleantis, a psychotherapist in California and the author of The Next Happy (2015), says that behind such bromides ‘is a kind of wish of parents or ourselves that we’re not bound by our talents, by our genetics, by our temperament, by our character. I think it really creates shame and guilt and feelings of failure.’

‘What it essentially says to our children,’ adds Penelope Trunk, author of Brazen Careerist: The New Rules for Success (2007), ‘is that, if they don’t achieve their dreams, they have no one to blame but themselves.’ Indeed, the transition to adulthood is already overwrought, and it’s made only more difficult when you think you can do anything and then feel completely incompetent when you can’t.

The dangers are legion. Unrealistic plans lead to a waste of time and money. When a C‑student spins her wheels planning on medical school, other, more lucrative and realistic careers – say in business or education – fall by the wayside. And the ambition gap has led to increased dissatisfaction across working life. Deloitte’s 2010 Shift Index revealed that 80 per cent of workers were dissatisfied in their jobs. By 2013, the figure had jumped to 89 per cent.

The situation even endangers health. In 2007, psychologists from the US and Canada followed 81 university undergraduates for a semester and concluded that those persisting in unattainable goals had higher concentrations of cortisol, an inflammatory hormone associated with adverse medical outcomes, and were more prone to colds.

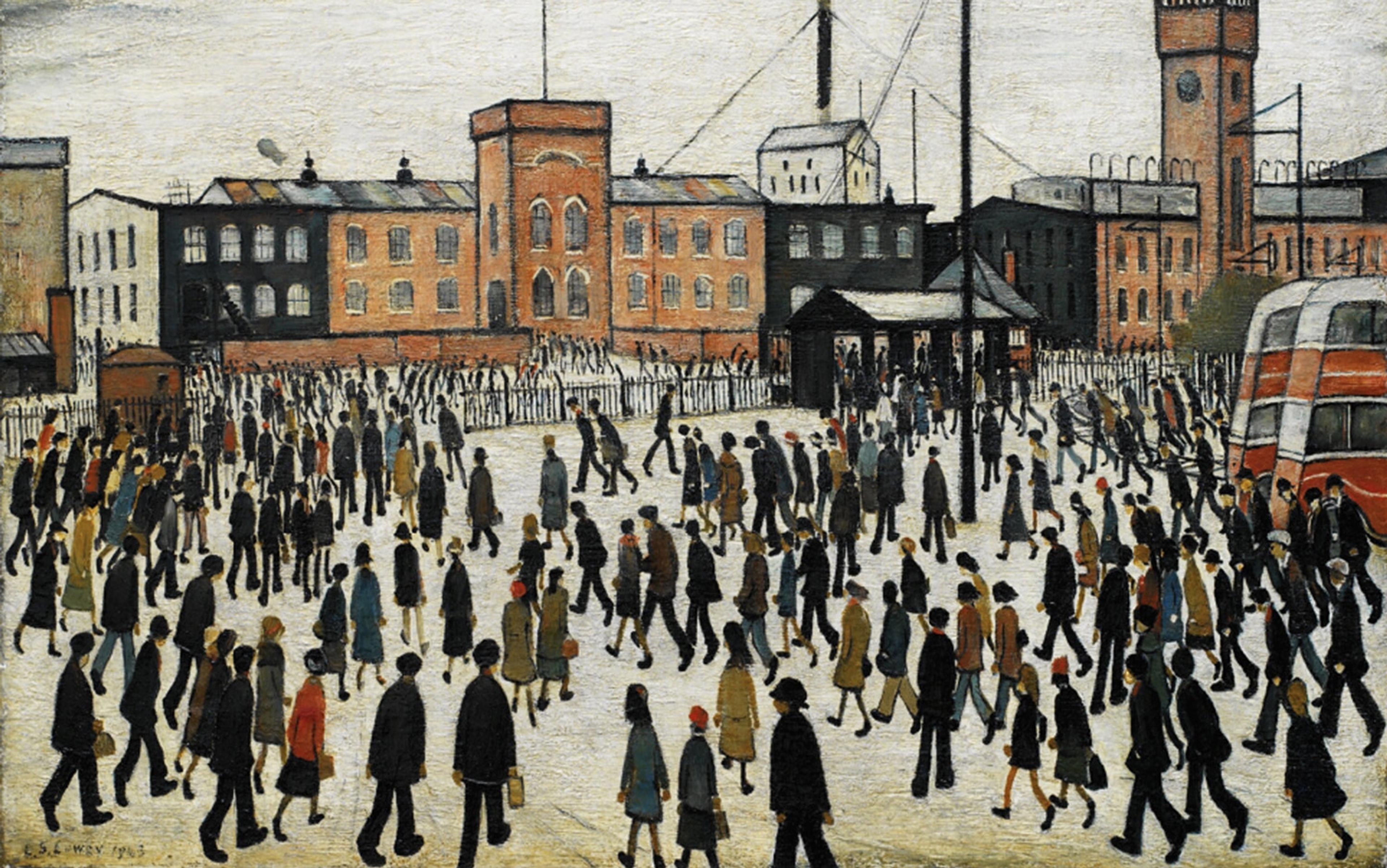

In many ways, where work is concerned, we live in a gilded age. Ask octogenarians if they believed they could do anything, and they’d be incredulous: wars, the Great Depression, out-of-reach education, as well as widespread discrimination made the idea of a dream career laughable for most. For generations, work was a means to an end, that end being food on the table, a roof overhead, and clothes on their backs.

Roman Krznaric, founding faculty member of The School of Life in London, says that his father, a refugee who left Poland for Australia, was a talented musician and linguist, but would have never expected that to be part of his working life. We’ve seen ‘rising expectations among everybody for work that’s more than just a salary,’ says Krznaric. ‘You see this among people who are highly educated or [those who] don’t have very many qualifications, and that helps explain why job dissatisfaction tends to rise over the past couple of decades, because people are asking … to use their talents or passions in their work.’

The shift in expectation has resulted in tremendous anxiety over achieving these goals and, paradoxically, sheer delusion. Point out to parents or teens just how difficult it can be to achieve such a high-level career and you’ll likely be treated to a catalogue of all the people who bucked the odds. Not just the Oprahs or the Steve Jobses who achieved super-status but the friend of a friend who just bought a modern all-glass home overlooking San Francisco Bay with his signing bonus, or the daughter of a work colleague who was cast in a new TV show, or the neighbour’s son who got a scholarship to Harvard.

And there’s the rub. If it’s possible for them, we want to believe that it’s possible for our children too. Besides, who wants to be the killjoy who has to remind the struggling math student that medicine likely isn’t an option? Or caution the dancer that, though she might find work in the field, she’ll likely have to supplement her income with waiting tables or working retail? Besides, technically it is possible. At what point do we abandon possible for probable, and encourage our children to do the same?

‘This links to the cult of positive thinking,’ says Krznaric, ‘where we’re always wanting to feel up and good and send positive messages… and so we feel that we should only be sending good messages and positive messages to our children and to young people. That it’s somehow wrong or bad or inappropriate to tell them: actually, it isn’t possible.’

The popular mantra comes from the actor Will Smith, who said: ‘Being realistic is the most commonly travelled road to mediocrity.’

But ‘mediocrity’ is a loaded term. Who, after all, wants to be ‘mediocre’ or ordinary? And yet, save for a few, aren’t we all? By implying that the only options are superstardom or mediocrity, we ignore where most of us ultimately land – that huge middle ground between anything and nothing much at all.

‘People confuse encouraging kids with telling them you can be anything you want to be,’ says Twenge. ‘People think they’re the same thing and they’re not.’

Someone who’s maybe a taxi driver or a nurse cannot believe that there’s a TV producer who seems to be more miserable than they are

Instead of emphasising you’re special, you’re great, ‘teach self-control and hard work,’ Twenge says. ‘Those two things are actually connected to success.’ Her eight-year-old recently announced plans for a career as a veterinarian (the career of choice for almost 10 per cent of American children between the ages of 10 and 12). Practising what she preaches, Twenge said it’s ‘a wonderful career… But, just so you know, you have to work really hard at math and science and do very well because it’s really hard to get into veterinary school.’ It might not feel as good as telling our kids they can be anything they want, she says, but it serves them far better.

Gwenyth has taken it upon herself to figure out what she needs to achieve her dream of becoming a marine biologist – the courses necessary (‘math, science’), the jobs she’ll have to take working toward it (‘taxi driver’), the skills she’ll need (‘how to drive a boat’).

Bolles suggests we remain curious when children share their career goals. By asking them what, exactly, appeals about a particular job, we – and they – gain insight into their values and perceived talents.

This self-reflection, which provides the backbone of Bolles’s Parachute model for job-hunters and career-changers, is something Krznaric agrees is crucial. ‘Fifteen- and 16-year-olds have all sorts of interesting things to say about who they are and what they care about.’ He thinks it’s fundamental for kids to be asking not so much what they want to be but who they want to be.

The answer might be surprising. Krznaric, who teaches his career course around the world and is father to six-year-old twins, is intrigued by something else he’s noticed. The people who take his course are just as likely to already have the so-called dream careers as those seeking them. ‘When I run these classes, it’s really curious that someone who’s maybe a taxi driver or a nurse cannot believe that in the same room there’s a TV producer who seems to be more miserable than they are in their jobs.’

Julie Lythcott-Haims, the author of How to Raise an Adult (2015) and a former dean of freshmen at Stanford University, routinely counselled students whose dreams were less lofty than what their parents expected – students who wanted to be nurses, not doctors, or high‑school teachers, not university professors. ‘I sat with those students and listened to them going through the motions of doing the work in the fields they felt were legitimate or expected or required, and I was interested in what this human in front of me actually wanted to do with their life, and how can I support them in listening to that voice in their own head?’

The problem, she says, isn’t telling kids you can be anything, it’s our narrow idea of what ‘anything’ is. ‘We’re equating it with prestige, power, title, money, certain sectors. If we could shift, over the next decade, toward high achievement being the equivalent of knowing your skills and your values and your passion, and living accordingly, imagine what a different world we’d be living in.’

Cleantis says the issues must be reframed: our dreams are more often about what we hope to feel than what we want to do. ‘There’s a kind of unspoken narrative: if I become this, if I do this, if I achieve this, then I will be loved, I will have self-acceptance,’ she says. By deconstructing what we hope to achieve emotionally, ‘it’s possible to find other ways of achieving that.’

Cal Newport, the author of So Good They Can’t Ignore You (2012) and a computer science researcher at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, adds that we have got the passion/purpose equation backwards. ‘It misrepresents how people actually end up passionate about their work,’ he says. ‘It assumes that people must have a pre-existing passion, and the only challenge is identifying it and raising the courage to pursue it. But this is nonsense.’ Passion doesn’t lead to purpose but rather, the other way around. People who get really good at something that’s useful and that the world values become passionate about what they’re doing. Finding a great career is a matter of picking something that feels useful and interesting. Not only will you find great meaning in the honing of the craft itself, but having a hard-won skill puts you in a position to dictate how your professional life unfolds.

Newport’s recommendation begs examination of another aspect of the ‘you-can-be-anything’ framework: should we expect to pursue a passion within our career or is it wiser to try to satisfy it outside of one? Sure, it’s convenient (and nice!) to be paid for something we’d love to do anyway. But is it realistic?

Marty Nemko, a career counsellor in the San Francisco Bay Area and the public radio host of Work with Marty Nemko, offers up a resounding ‘no’. He’s all for people pursuing their dreams, as a hobby. ‘Do what you love,’ he says, ‘but don’t expect to get paid for it.’ Of course, he says, there will be those who can – and do – make it in fields that are highly competitive. Maybe your passion for computer programming, or for splicing atoms, brushes up against career fields that offer plenty of opportunity. But, if like many, making a career out of your passion is a long-shot, instead of giving it up, incorporate it into your free time.

Lythcott-Haims encouraged her students to look at three things: what am I good at; what am I passionate about; and what are my values? Then, she told them to ask: ‘How can I spend a meaningful part of my week – whether career or hobby – living at the intersection of those things?’

‘You can be anything? It’s not true. You can’t be a dinosaur’

Maybe our parents and grandparents had it right when they pursued their passions and hobbies – which offered up meaning and mastery – in their free time. Like Krznaric’s father, who made music outside his job. Or like Nemko himself who gave up working as a professional pianist for psychology.

Krznaric suggests a slightly different model – that of the ‘wide achiever’ who does several jobs at the same time, such as someone who works as an accountant for three days a week and a photographer for two. It’s a smart approach in an unstable economy where, he says, ‘the average job lasts four years’. It also recognises that ‘who we are changes throughout our lives. We’re really bad judges of our future selves.’

‘You can be anything you want to be’ is pithy advice that isn’t helping most of the young launch careers or find satisfaction in life. If we really think about it, few of us mean it literally. Twenge has told her daughter that ‘when people say you can be anything, it’s not true. For example, you can’t be a dinosaur.’ Perhaps what we’re really trying to say to our children is that we trust in their ability to build a meaningful life.

‘[Adults] should say: be what you’re capable of,’ says Gwenyth, ‘not you could be anything. I’m not very good in dance. That’s like telling me I could be a professional dancer. No. No, I couldn’t be.’