I came to the UK from Bulgaria in 1990, and every job I saw advertised wanted experience. The application forms had box after box for me to list my previous jobs. But all I had ever done was go to school. I tried leaving those pages empty. The forms were handed back.

‘You need to fill that in, love,’ they told me at the jobcentre.

But I’m 19. I have nothing to fill it in with yet.

‘Go to a careers adviser. They’ll sort you out.’

So, I went, although I did not need careers advice. I knew what kind of career I wanted and they didn’t advertise for it at the jobcentre. Journalism was in my blood. Back home, my father was in the process of founding a new daily broadsheet. My mother worked for the radio, for Bulgaria’s world service. I could speak three languages and had left an English degree course to follow my heart to the UK. Now my husband and I lived in Devon, in a cold, rented house a mile from the nearest bus stop. We had no money, but I wouldn’t dream of claiming benefits. My career had simply been stalled by circumstance. As soon as I had my circumstances in order, everything would be back on track.

In the meantime, I needed a job. Yet it seemed impossible — I couldn’t get a job until I’d had a job. How did people ever break that cycle? How did they find something to put into those blank boxes? All I had done so far was go to school and get married.

‘Did you not have a Saturday job or something?’ asked the careers woman kindly. ‘Just think, anything at all, just so you can put it on the application form.’

I looked at her and saw myself reflected in her horn-rimmed glasses. My hair too long, my jeans too marbled, my accent unfamiliar. The Berlin Wall had come down the year before. It would be a few more years before Britain looked east for plumbers and nannies, and English ears became accustomed to our steely consonants.

‘Anything?’ I asked in confusion.

‘Yes, anything at all — did you babysit for a neighbour, or sell lemonade from a stall in your garden, or help at a charity event?’

I looked at her through my own horn-rimmed glasses. I looked at her dangly earrings, her chunky necklace. Back home in Bulgaria, no one ever used babysitters. That was a society of total employment: everyone worked, not just dads but mums, too. So we were all latchkey kids, without the stigma. But then, the retirement age was low — no older than 55 for women — which meant there were always plenty of ‘grannies’ about. Random old ladies, sitting on benches outside your block of flats, making sure that your skirt wasn’t too short and that you didn’t chew gum while you spoke. Who needed a babysitter with them around?

As for selling lemonade, I wanted to, honest to God. There was something I needed money for, I forget what now, but I desired it with a crazed intensity. I even wrote up a sign, but it wasn’t for lemonade, it was for ayryan, a watered-down yogurt drink. When my parents saw my advertisement, they looked at each other and took a deep breath. They carefully praised my initiative and then folded the sign away. This was socialist Bulgaria. We might get into trouble. Private enterprise was not compatible with ideological reality.

As for charity events: there were no charity events. The whole country was a charity case, its entire economy built on a warped charity model — that you give what you can and take what you need — with the crucial difference that people were coerced into it. For all their big foreheads, Marx and Lenin never gave much thought to the base human desire to feel better than others, to have shinier things. Even when you make it impossible for people to compete openly, they still want to compete. They scurry and scamper and do what they can to make better versions of themselves. And if they glimpse someone less fortunate, they don’t feel pity — they gloat. In this atmosphere, charity didn’t stand a chance. It would be many years before this peculiar Western concept met with anything other than incredulity in Bulgaria.

‘But what about at school?’ the nice careers lady persevered. ‘Did you not do any work experience?’

At last, a light bulb went ping. I could list my praktika, my work experience! When she’d said ‘work’, I’d immediately thought ‘paid’. I was in the West, after all, where money was king, and I had yet to earn any myself. But if it was experience they were after — well, I had plenty.

It was a snug, cosy, book-lined den and, at 15 years old, I was thrilled to wear a regulation blue coat over my own clothes. Books were very precious; those who handled them had to be properly attired. I was like a lab-coated assistant in the laboratory of the intellect. I’d stand guard at the counter. The door would open, the bell would ring, and I would spring to attention. The customer would point at the shelf behind me, and I would bring the book down gently and then watch like a hawk as its jacket was examined, front and back, and its weight measured with a bounce of the hand. Then a few pages would turn. Some books arrived half-baked, with folios still uncut, their pages tenting together. I would get a knife and slice them apart, like a surgeon.

Once it was agreed that this was indeed a book, a good book, that it felt right in the hand, and — look! — its pages came apart obligingly, payment would be offered. I’d put the money in the till. I’d lay the book flat on the stack of brown paper on the counter. And then, the best bit (we’d even had tutorials on how to do this): I would wrap it snugly in the paper, tucking in the corners and sealing the package with tape from a dispenser.

All this had given me enormous pleasure. When the week’s praktika was over, I begged the bookshop lady to let me come again. ‘It could be our secret!’ I pleaded. ‘You could go for a coffee break. Just let me look after the shop.’ She smiled sadly and shook her head. It was not allowed. I was too young to work. I could only do work experience.

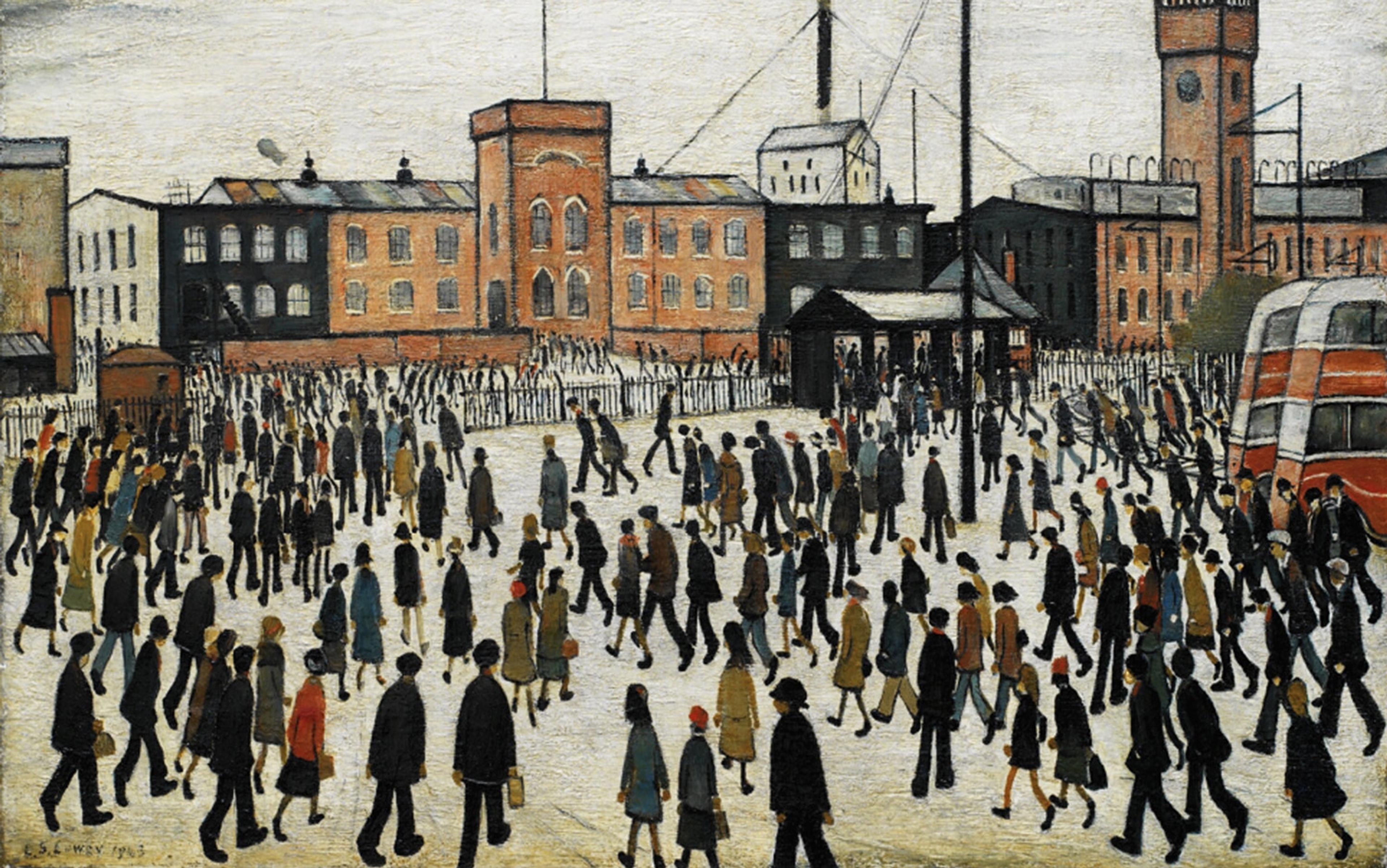

That was in the spring, when the lime trees were in blossom. By the time the grass in the city parks was turning yellow, I had been placed in a factory near the centre of town. My classmates and I wore white coats and large protective goggles, which made my face sweat and my eyes squint. The summer sun spilt in through the giant plate-glass windows, dazzling us. I cannot tell you now what we did. I remember small plastic objects, discs, rectangles and squares, and wires, and pearly bulbs that were pleasant to touch. We had to do something with these disparate parts, but what? Surely they didn’t leave a bunch of teenagers to assemble electrical goods?

Whatever we did, we didn’t do it for long. Perhaps we did it so badly that they sent us home early. We weren’t there to work anyway; not really. The experience of work was enough. And for me, it was: I’d seen the blank faces of the people in the factory, I’d felt their ennui. If this was work, I wanted nothing more to do with it.

By autumn, my class was off again, this time to a canning plant near the Danube where we would process the grapes and the tomatoes of the season’s harvest, preserving them for our nation to consume throughout the winter. This was more like it — real work, noble work. We had an important job to do, and we’d get sweaty and dirty doing it. After four weeks’ hard labour, far from home and holed up in grotty communal accommodation, I’d made enough money to buy a bottle of flowery perfume. Pocket money, certainly not the rate for the job. The fact that I spent it on something so frivolous says it all: this was just pretend. This was not work, the real thing, the career I had imagined for myself in the future, that would occupy my mind and satisfy my soul and feed my family.

And here I was now, in England, my career derailed, my circumstances temporary. If experiences would be enough to get a job, then I had them. I told the kind careers lady about the bookshop, and about the electronics factory, and about the canning plant. Her eyes shone. ‘See, you have worked!’ she said, clapping her hands under her chin. ‘You really have worked.’ Then her head tilted to one side. ‘You poor thing,’ she muttered. She looked through me, I suppose, to posters of beefy women in overalls waving hammers and sickles. And I looked at her and imagined other teenagers in my seat. Local teenagers, with droopy hair and rock bands on their T-shirts, who might think that washing the family car or getting the neighbour’s shopping in was a job, a job for which they must get paid.

I imagined them seeing the blanks on an application form and filling them in, confidently, their domestic experiences standing in for the real thing. And I imagined the recruiters, the managers and that whole as-yet-unmet boss-class of people reading those application forms and nodding at all the blank boxes neatly filled in, happy to buy the fiction of the pretend employment. The old joke from the communist days goes: ‘We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.’ Here it was different: you pretend you’ve worked, and they pretend to believe you. Truly, this was the land of opportunity.

If I could pretend that my praktika had been real work, why not go one step further: why not pretend I had done something worth pretending? Instead of factories and shops, why not galleries and museums, universities and hospitals? People in the UK were still too timid to peek behind the Iron Curtain. I could have fun filling in the blanks.