Listen to this essay

Attend almost any medical appointment today and you’ll likely hear the word inflammation hovering in the background like a confusing puzzle piece that seems important even though it isn’t the focus of diagnosis or treatment. ‘You have some longer-term damage to your gut after the infection,’ a gastroenterologist explained to me recently, ‘the technical term is that you have inflammation.’

Enquire further, and it doesn’t get any easier to pin down. The year prior, another doctor, reading a pathology report, told me: ‘Good news – this biopsy isn’t endometriosis or cancer, it’s just non-specific chronic inflammation.’ When I asked what that meant, they suggested I check with the pathologist.

The pathologist, in turn, explained that she had simply classified the tissue according to the textbook. Simple – or oversimplified? Weren’t endometriosis and cancer also inflammatory conditions? Why did all these answers mean such different things? How did they know it was ‘chronic’ specifically? Did I need to get rid of it? Would the stress of worrying about all this make my inflammation worse? Is inflammation actually good in small doses, or a specific entity at all?

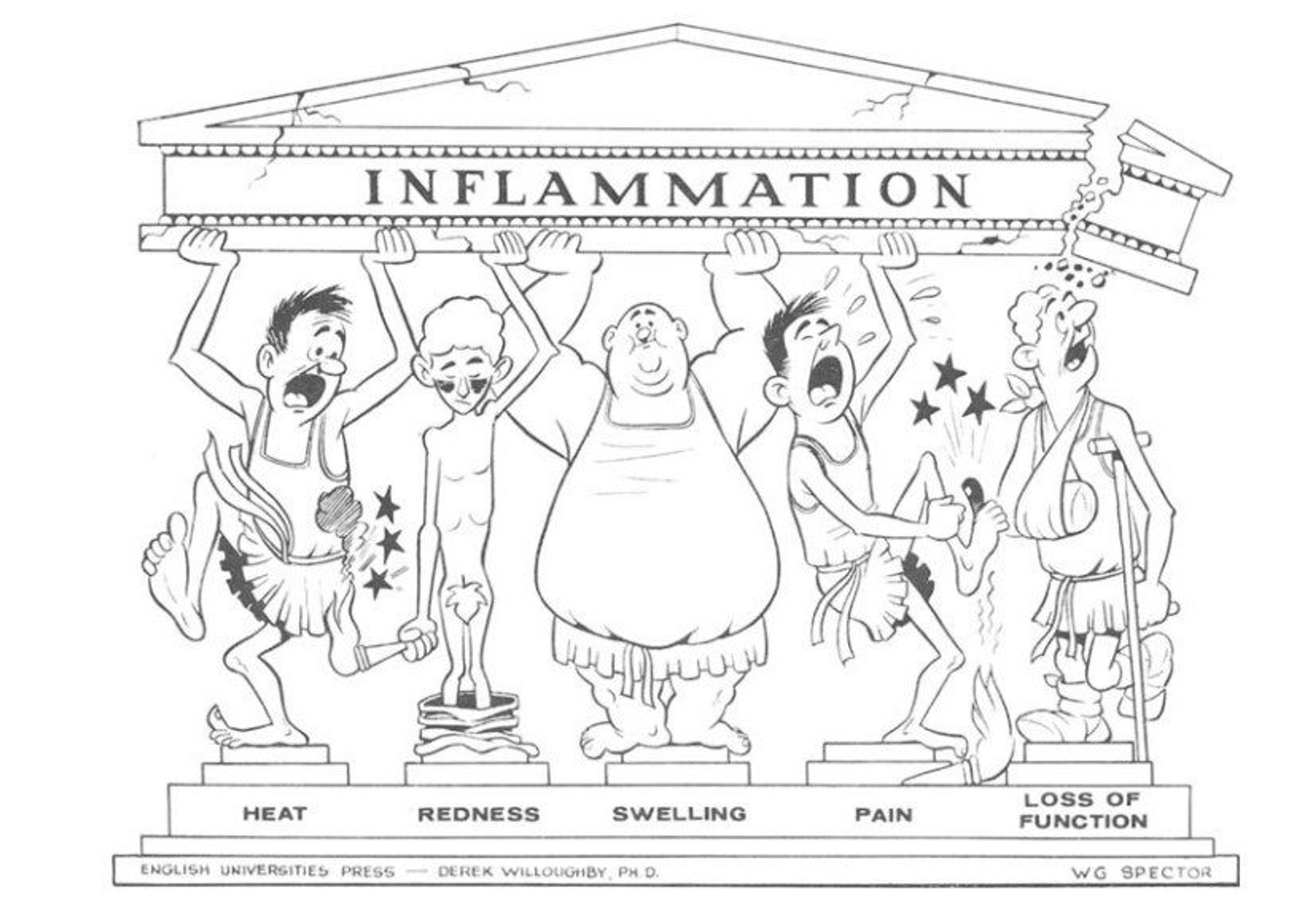

Unlike chronic inflammation, the kind of acute inflammation described in medical textbooks has a long and stable history. In Western medical culture, it has been understood as our essential healing response to injury or infection – ‘the body’s unique mechanism to maintain its integrity in response to macroscopic and microscopic injuries,’ as the health psychologist Jeanette Bennett and colleagues put it. From a sprained ankle to an infected cut, acute inflammation is the main reason our bodies respond and recover. It has classically been defined by five cardinal signs: redness, swelling, heat, pain, and loss of function. Advances in microscopy, cell biology, immunology and related fields have continued to refine this paradigm, with inflammation being described as the activation of immune and non-immune cells, inflammatory mediators, and systemic energy-saving responses following injury, infection or disease, affecting a range of body systems, sleep, appetite, and behaviour.

The five cardinal signs of inflammation, designed for the International Inflammation Club by D A Willoughby and W G Spector in the 1960s. The four original signs of inflammation (calor, rubor, tumor et dolor) were described by Celsus in the 1st century CE, and a fifth (function laesa) was added by Rudolf Virchow in 1871.

This acute version of inflammation, though often painful, is protective: swelling brings immune ‘defenders’ to the wound, heat makes the environment hostile to pathogens, and pain forces rest so the body can repair itself. Ancient civilisations treated such inflammation with plants containing what science now calls salicylates, compounds used in aspirin. Musculoskeletal specialists study how to optimise healing with temperature, pressure, behaviour change, and chemical therapies. Today, the global market for anti-inflammatory drugs amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars annually. That this explanation of acute inflammation makes intuitive sense both inside and outside medicine is testament to its longstanding cultural acceptance.

Is chronic inflammation a defence gone awry, or a misguided attempt by the body to heal itself?

The anomaly on the scene is chronic inflammation. Unlike the sharp, visible signs of acute inflammation, chronic inflammation is low grade – simmering quietly but occasionally flaring up dramatically – and it’s systemic, affecting the whole body rather than staying at the site of injury. It appears to accompany many chronic diseases, both as a cause and as a consequence. Chronic inflammation has different triggers, chronicity, severity, symptoms, and biomarkers than acute inflammation – so different that the two seem unrelated at first glance. What ties them together – and explains why both are called inflammation – is the same immune response: white blood cells spring into action, releasing cytokines that send chemical signals and alter tissues. In acute inflammation, this activity is so important for healing that some branches of medicine now actively discourage use of anti-inflammatory treatments. In chronic inflammation, the process never fully turns off, leaving a persistent, smouldering state that can gradually damage the body rather than repair it.

Chronic inflammation complicates the picture. It rarely shows the familiar signs of redness, swelling or heat, and may arise without clear cause – sometimes linked to infection or injury, but often not. Some researchers suggest it’s less a disease than a ‘physiological pathway through which environments early in life shape trajectories of health in adulthood.’ In this view, early exposure to stress, poor nutrition or pollution can tune the body’s immune responses for life – priming them to overreact or stay switched on even when no threat remains. Testing offers little certainty either: blood markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) indicate when inflammation is present but not where or why, and readings can vary depending on the type of test, its sensitivity, and how results are interpreted. As the nutritional scientist A Catharine Ross notes, using the same word inflammation for both acute and chronic forms may obscure the distinct biological processes driving each.

Still, the consequences of chronic inflammation are profound. The list of conditions that can now be grouped under ‘chronic inflammatory diseases’ is strikingly long: obesity, asthma, heart disease, irritable bowel, Alzheimer’s, cancer, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, endometriosis, stroke, Type 2 diabetes, HIV/AIDS, fibromyalgia, and even some forms of depression and schizophrenia. Many of these illnesses are rising worldwide, amounting to ‘some of the most significant biomedical urgencies of our time’, as the immunologist Martin Trapecar puts it. When aggregated, chronic inflammatory conditions today represent ‘the most significant cause of death in the world’, in the words of the longevity researcher David Furman and colleagues.

Little wonder commentators now talk about a ‘silent epidemic’ of chronic inflammation. Governments are being urged to promote ‘anti-inflammatory lifestyles’ by intervening in diet, physical activity, stress, sleep, infrastructure, and social disparities. Much of this advice bears close resemblance to decades-old public health guidance around obesity and diet-related non-communicable disease – approaches that, so far, have had little success at the population level. Social media influencers offer myriad advice on all things anti-inflammatory. Meanwhile, medical specialists in fields as varied as chiropractic, gastroenterology, and psychology are weaving inflammation into their theories, explanations and advice on best practice.

And yet, for all this attention – and despite centuries of medical study of inflammation in general – inflammation in its chronic form remains elusive. It doesn’t follow the textbook signs, may cause no obvious symptoms, and can even escape detection on standard tests. Its triggers are often uncertain, its biomarkers unreliable, and scientists still debate what role it truly plays: is chronic inflammation a defence gone awry, or a misguided attempt by the body to heal itself? As anomalies mount, the classic model of inflammation as a short-term healing process begins to fracture. Scientists, clinicians and patients alike are left working with puzzle pieces that no longer fit. The growing contradictions suggest we are not merely confronting a clinical puzzle but the stirrings of a paradigm crisis – an unravelling of the framework that once defined inflammation itself.

As research has advanced, the contradictions surrounding chronic inflammation have only multiplied. Clinically, it does not form a coherent disease category or specialist area. For example, coronary artery disease is linked to inflammation, yet ‘no strictly anti-inflammatory drugs are used to treat patients with coronary artery disease’, as the cardiologist Robert Harrington puts it. Endometriosis is defined as inflammatory, but innovation in treatment still prioritises surgery and hormones rather than tackling systemic inflammation. Other inflammatory conditions, like arthritis, are treated with anti-inflammatories. Despite the ubiquity of the term, patients with chronic inflammatory conditions rarely see an immunologist, the medical specialisation otherwise dedicated to the immune system, and most national health systems do not recognise ‘chronic inflammation’ as a discrete diagnostic category.

The picture grows only more complex when chronic inflammation appears in contexts that fall outside the standard biomedical frame. Some studies suggest it can influence social behaviour, either promoting withdrawal or fostering affinity, depending on circumstances. Small doses can trigger ‘sickness behaviour’ such as fatigue and isolation, says the psychologist Emily Lindsay. Other research implicates it in shaping long-term health trajectories through epigenetic pathways. The microbiome is increasingly recognised as a key player, capable of accelerating or mitigating inflammatory processes. And clear sex-linked differences have also been documented: women are disproportionately affected by chronic inflammatory conditions in terms of incidence, prognosis and response to treatment.

It is clear that the inflammation puzzle pieces no longer fit the picture on the box

Confronted with this tangle of anomalies, some researchers have begun to sketch new paradigms. One proposal reframes inflammation as a signal within a dynamic system of feedback loops connecting the body, environment and society. Another interprets it as a homeostatic control mechanism, where the population-level rise of chronic inflammation indicates that the body system itself is overwhelmed by the contemporary world we have created. Others point out that the problem may lie in the biomedical model’s own architecture: by siloing disease into organs and specialties, Western medicine may be ill-equipped to grasp phenomena that crosscut the whole body. Some call for broadening our assumptions about the immune system itself, while others push in the opposite direction, hardening the traditional paradigm and resisting change.

What is clear is that the inflammation puzzle pieces no longer fit the picture on the box. Observations and patient experiences resist explanation, the old rules of ‘normal science’ blur, advice is contested, and contradictions mount. With social pressure for reform around chronic inflammatory conditions intensifying and costs across health systems rising, disappointment and disagreement within medicine deepens. The result is a crisis: a sense that the prevailing paradigm of inflammation is breaking down.

Could this be the signal of a scientific revolution? What constitutes such a revolution, anyway, and why does it matter? In his groundbreaking book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), the philosopher Thomas Kuhn challenged the belief that science advances in a steady, incremental march. The old assumption was that knowledge simply accumulates through experiments and data. Kuhn argued instead that science moves in cycles. For long stretches, researchers practise what he called normal science, solving problems within the rules of an accepted paradigm – the shared framework of theories, methods and assumptions that defines how a field understands the world. It is like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle: the picture on the box represents the paradigm, and the work serves to fit the pieces into place. But when too many pieces no longer fit – when anomalies pile up and the picture itself begins to look wrong – the paradigm falters. At that point, a revolution occurs: old assumptions collapse, new ones take their place, and scientific communities reorganise around a different worldview.

We can describe Kuhn’s process of scientific progress in three phases. First, periods of normal science proceed successfully under a stable paradigm, with anomalies often dismissed as error, pseudoscience or background noise. Second, anomalies multiply until they can no longer be ignored, generating a state of crisis. Third, resolution comes with the adoption of a new paradigm, one that reframes the problem, establishes a new puzzle to solve, and changes the very questions science can ask. Rejection of an old paradigm, Kuhn observed, is rarely complete or immediate: it tends to occur only once there is a viable alternative and a crisis that creates urgency. Not all scientists accept the change, and not all can be accommodated by it, but the centre of gravity shifts.

As the physician Sophia Samuel remarks, when medicine experiences a changing paradigm, ‘What we thought we knew is then re-examined in the light of new information and possibly recast in an entirely different way.’ With a new paradigm come new methods and new disciplines. New kinds of question are embraced, and new kinds of researchers and practitioners are required. Medicine, in particular, feels the effects beyond the laboratory: clinical categories change, treatments shift, patient trust wavers, and whole areas of life and practice once considered marginal can become central to health.

Chronic inflammation is generating contradictions that the prevailing paradigm struggles to contain

The microbiome offers a recent example. With the rise of germ theory in the 19th century, microbes were cast as enemies of the body. By the 2010s, after decades of mounting anomalies, a new paradigm had stabilised: microbes were recognised not only as threats but also as vital partners in health. This shift produced new professions, interdisciplinary research centres, household products, clinical practices, and even policy frameworks. Clinicians began to think less about eradication and more about what Samuel calls ‘negotiated symbiosis’, balancing antimicrobial resistance with protection of the microbiome. Industry began to capitalise on the opportunity afforded by people seeking to foster a healthy microbiome, creating entirely new products, from probiotic tablets to prebiotic foods. By the decade’s end, the microbiome had become mainstream enough that Forbes declared the 2010s ‘The Decade of the Microbiome’.

Standing where we are today, in the clamour of the mid-2020s, there are early signs that inflammation could be undergoing a similar transformation. Normal science has long served us well under the acute model – explaining swelling, pain, and repair. But chronic inflammation, sprawling across multiple diseases, is generating contradictions that the prevailing paradigm struggles to contain.

Kuhn’s framework is not perfect – critics note its vagueness, and its tendency to divide science into overly tidy phases – yet it remains one of the most influential accounts of how scientific progress unfolds. Could it help us anticipate a scientific revolution around inflammation? And what would be gained if we could?

One benefit might be a new way of understanding illness and health itself, giving us, finally, the tools to address the chronic conditions of our time. Take obesity, today considered to be both a chronic disease and a risk factor that predisposes people to a range of other diseases. For a long time, we have considered obesity to be a matter of energy imbalance, with obesity interventions focused largely on diet (energy intake) and exercise (energy expenditure). This approach is underpinned by the paradigm of causal reasoning, and has led to significant social stigma, guilt and stress among patients whose lifestyles come under medical and public scrutiny. It hasn’t led to reduced population-level obesity or associated diseases, and may even be causing more obesity because of failure to understand its cause. With growing acknowledgement that obesity is a low-grade inflammatory condition, a scientific revolution around inflammation could open new avenues for treatment and health.

Or take Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that destroys memory and thinking, typically attributed to abnormal deposits called amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain. Current treatments seek to slow the worsening of symptoms by targeting these amyloid plaques and tangles. Yet researchers have noted links between Alzheimer’s and inflammation since the 1990s, with inflammation a cause and a consequence of the condition. Progressing from theory to intervention when a paradigm is not dominant takes time but, 30 years later, a large proportion of therapies in clinical trials are anti-inflammatory compounds. Such interventions mobilise the immune system or target systemic chronic inflammation, and may have serendipitous benefits for other chronic inflammatory conditions too.

From cancer to psoriasis, patients have been dealing with what we now call ‘chronic inflammatory conditions’ for a long time. Some have been well served by the medical community but, mostly, treatments are plagued by unknowns. Many such patients report feeling gaslit, disbelieved and ignored by the medical community, and discriminated against by employers, medical systems and funders.

Take endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory condition now thought to affect one in 10 people assigned female at birth (one in seven in Australia). Diagnosis can take years, with symptoms downplayed or outright dismissed. Treatment options vary, with countless accounts of trial and error, successes, setbacks, confusion and disappointment when cure cannot be attained. Many of these experiences erode trust in medicine, but the majority of practitioners aren’t inherently bad people, or misogynistic, or poorly educated. Rather, people across the health system – particularly patients – are caught in the collateral damage of a paradigmatic crisis. The effect on patients may well resemble post-traumatic stress.

This frustrating patient and practitioner experience may be a fertile place to look for new paradigms. In the early 18th century, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu drew on her own suffering with smallpox, together with her observations of Turkish women practising inoculation, to promote the procedure in England. At the time, the disease was largely explained by miasma theory – the belief that the illness arose from foul vapours or ‘bad air’ drifting up from swamps, rotting matter or dirt. This view was entwined with an even older medical model, the theory of the four humours, which held that health depended on balancing four bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Illness was thought to occur when these fluids fell out of balance, whether from diet, environment or exposure to corrupted air. Within such frameworks, there was little sense that disease might have a single, identifiable cause, or that intervening in the body rather than the source of illness might yield future protection.

Variolation (vaccination) unsettled the prevailing logic. By deliberately exposing people to a small dose of smallpox, Turkish women demonstrated that the disease could be both provoked and prevented in precise, repeatable ways. Montagu’s decision to have her own children variolated, and her advocacy at court, brought the practice into Western medicine. Though still far from the fully developed germ theory of the 19th century, variolation cracked open the possibility that illness stemmed from specific agents that might be managed directly – and, in doing so, helped lay the groundwork for a paradigm shift in how disease was understood.

A revolution from the grassroots may well be playing out today, as well. In the absence of medical attention, the patient conversation around chronic inflammation is in some respects more advanced – and certainly more open to new perspectives – than the one playing out in science. Patients are organised into communities and groups at scale, facilitated by online education and social media. On Facebook, endometriosis groups have more than a quarter of a million members. Through these networks, patients share information almost instantaneously; they develop hypotheses, test interventions, compare results, and even coin the names of new conditions.

When paradigms begin to shift, patient communities often move faster than scientific institutions

The case of Long COVID is especially telling. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, people with persistent symptoms found themselves dismissed by clinicians or excluded from early studies – because they did not fit the prevailing paradigm of infectious disease. Online, however, patients compared experiences, documented patterns of fatigue, brain fog and inflammation, and insisted that what they were living through was not merely anxiety or deconditioning but a new syndrome. They gave it a name – Long COVID – and in doing so forced medicine to recognise and study it. What began as a patient-generated category quickly spurred research programmes, funding streams and new diagnostic frameworks.

When paradigms begin to shift, patient communities often move faster than scientific institutions. By harnessing technology and treating lived experience as a kind of expertise, patients not only generate knowledge for themselves but sometimes propel medicine to catch up. If science is indeed facing a crisis over inflammation, it may be in these patient-led spaces that the first outlines of new paradigms appear.

Then there are the medical practitioners and clinicians. Some, still anchored in the old view, may dismiss perspectives – or patients – that fall outside the prevailing paradigm. But many others race to keep up with the evidence as it evolves, to implement new findings safely, and to explain to patients that uncertainty is real: research is incomplete, clinical guidelines and education lag behind, and there are few cures or silver bullets. Many clinicians notice patterns among their patients and develop hunches, yet they’re too busy to document or study these systematically. Patients, unaware of the hidden labour behind the scenes, may voice frustration – informally or through complaints – about imperfect outcomes, side effects, changing advice or incomplete recovery. For practitioners in fields that confront chronic inflammatory conditions daily – particularly in women’s health – the strain is intense. Studies find that more than half experience burnout, frustration, or a sense of futility. Such exhaustion and moral distress are the psychological hallmarks of a system under crisis.

Researchers are part of this process too. How they respond to anomalies – and to the blurring edges of normal science – shapes the course of progress itself. Some, as Kuhn observed, seize the moment: they form new communities to explore emerging paradigms, though only a few of these ventures will ultimately improve understanding or outcomes. Others remain caught in a state of flux. And some, whose identities and careers are deeply entwined with the prevailing order, continue to work within a failing paradigm. They may hesitate to revise their lectures, or dismiss novel approaches, or defend established methods as they seek to protect the boundaries of the old worldview. In this way, scientific revolutions are both creative and destructive – and that tension may help explain the long and troubling history of bullying in universities.

When it comes to chronic inflammation, Kuhn’s lens lets us see the current confusion in a different light. Rather than dismissing contradictions as noise, we can read them as signals that the puzzle pieces no longer fit the picture on the box. That shift in perspective opens space for change. It invites us to imagine new paradigms, to ask which emerging models better account for the growing pile of anomalies, and to bring together fresh communities of enquiry around them. It also reminds us to confront the human costs of transition – borne by patients, practitioners and researchers alike – when the old rules no longer hold. If we navigate this crisis well, what now looks like disarray might, in retrospect, mark the dawn of a medical revolution. The 2020s, we may say one day, were the Decade of Inflammation.