As far as aspirations go, MarkAlain Dery’s might seem strange: giving rapid, mouth-swab tests for human immunodeficiency virus to celebrities. ‘I’ll swab anything I can swab,’ says Dery. ‘My dream is to get L’il Wayne or some other big rapper.’ As he envisions it, the swabbing occurs in front of a large crowd of people, mostly black, who all decide to follow suit.

Dery’s dream seems less odd when you consider his surroundings. An infectious disease doctor at Tulane University, Dery treats people living with HIV in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the two largest cities in the southern state of Louisiana, which itself has the fourth-highest rate of HIV in the United States, just behind New York, Florida and Maryland. In the cities, it’s worse. Baton Rouge ranks number one among US metropolitan regions for AIDS, which is the end-stage sickness caused by the virus and which inevitably leads to early death. New Orleans, meanwhile, ranks second among large US metro regions for the rate of HIV.

In the 30 years since the first cases were reported in the US, HIV – transmitted predominantly through unprotected sex and sharing needles – has become a disease that thrives on poverty, sexual stigma and racial inequality. For this reason, the geography of the disease has shifted from urban coastal regions to the southern states: where those problems are most prevalent, so is the virus.

Louisiana’s HIV epidemic is a direct consequence of its severe social conditions. The state is among the poorest and worst-educated in the country, and holds the ranking as the most incarcerated. Moral opposition to homosexuality is heavily legislated. Religious and political conservatism reign, leading to discriminatory laws and policies. The conglomeration of factors at play in Louisiana starkly illustrates why HIV continues to spread in the US despite the fact that it is entirely preventable, and why so many Americans are still dying of AIDS when the virus is almost entirely treatable.

The numbers are grim. As of 2011, approximately 17,735 people were living with HIV in Louisiana, out of 1.1 million nationwide. Some 50 per cent had been diagnosed with AIDS, versus the national estimated rate of 15.8 per cent. Several thousand more people in Louisiana – an estimated 1,858 in New Orleans alone – are living with HIV and don’t know it.

In a dark auditorium filled with Tulane Medical School students, Dery shows slides explaining why the social conditions of Louisiana are so well suited for the biology of the virus. With his motorcycle boots and slicked hair, he looks better-matched to a stage than to a lecture hall. But his unconventional appearance – heavily tattooed, including the word ‘pacifist’ on his wrist and dressed in a black three-piece suit, the skateboard he rode to work stashed in a corner – helps keep their attention. His frequent swipes at the state government and other powers-that-be all seem like part of the show.

A virus with genetic material made of single-stranded RNA, HIV is especially susceptible to the introduction of errors during replication. ‘It’s an evolutionary advantage to have a lot of errors,’ says Dery. Those errors, or mutations, enable the virus to evade the immune system, which is unable to recognise each new form. Once inside a human host, the RNA is converted into double-stranded DNA and spliced into the host’s genome. ‘Once you’re infected, you’re infected forever,’ Dery tells the room, emphasis on forever.

Medical strides, however, have turned HIV into a chronic disease. Most infected people can live a normal, relatively healthy life as long as they are diagnosed early enough and take their medication as prescribed. Today’s antiretroviral drugs suppress the viral load – that is, they lower the amount of virus circulating in the bloodstream – to the extent that someone in proper care has almost no risk of infecting someone else.

In reality, only about a third of HIV-positive people reach that point. Dery pauses the slide show on a bar graph that explains why. Of all the people infected with HIV, only 82 per cent are diagnosed. Fewer are linked to medical care, still fewer stay in care, and even fewer reach the crucial point of viral suppression.

This downward spiral – each bar on the graph shorter than the preceding one – is no different in Louisiana than in the rest of the country. What distinguishes this state is the abundance of superlatives: the most, the worst, the highest. All the factors that trigger drop-offs at each stage of care are present to an extreme extent in Louisiana, thereby harming a greater proportion of the population than in other states. For HIV, Louisiana’s conservative laws, poverty and shame-inducing cultural stigmas create the perfect ecology for mass viral replication.

Dery, who is originally from Los Angeles, stands at the screen, the glow from the fleur-de-lis – the symbol of New Orleans – that has replaced the apple on his laptop cover the only other light in the room. He points to the first bar on the graph, the one representing the unaware population, those who are positive but undiagnosed. ‘They are driving the epidemic,’ he says. ‘An unchecked viral load is what causes problems.’

Outside the lecture hall, a few blocks up Tulane Avenue, which runs through the Central Business District, new medical facilities are being built. A Whole Foods recently opened nearby, anticipating an impending influx of staff and students. But the post-Hurricane Katrina revitalisation is not so apparent in the side streets. The quiet roads off the avenue are lined with single-storey houses, many no more than shacks in disrepair, with porches bolstered by rotting wood and yards overgrown with weeds. At night, prostitution takes the place of construction on Tulane Avenue.

These streets show the reality behind the bar graph, the poverty that denies people access to care. Louisiana has the second-highest poverty rate in the country and about 3,900 homeless people. Between 2008 and 2012, 19 per cent of the Louisiana population were living below the federal poverty level. In New Orleans, that number climbs to 27 per cent, nearly twice the national average. The Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness has called New Orleans ‘the most blighted city in the nation’. Louisiana’s infant mortality rate, a barometer for overall health and welfare, is twice the national average (14 versus 7 per 1,000 births for black residents and 10 versus 7 for whites).

The infection rate among blacks is six times higher than among whites in Louisiana

Poverty is ideal for the spread of HIV because of the many ways in which it disrupts care. ‘If they don’t know where they’re going to sleep tonight, if they don’t know where their next meal is coming from, that can make it very hard for them to make it to a doctor’s appointment,’ said Brandi Bowen, programme director for the New Orleans Regional AIDS Planning Council (NORAPC), which oversees the distribution of state and federal funding for local patients in need. ‘If it were not for Ryan White funding,’ she added, referring to the federal assistance programme for HIV/AIDS patients enacted in 1990, ‘our patients literally would have no access, no way that they could pay for their medications themselves, no way that they could afford to stay in housing.’ In New Orleans, almost 4,000 people living with HIV/AIDS are in need of housing assistance.

Race, inextricably tied to poverty in Louisiana as in the rest of the US, is now a major risk factor for HIV. Black men make up 33 per cent of the overall state population of 4.4 million, but account for 74 per cent of all new HIV cases, according to statistics from 2010. The infection rate among blacks is six times higher than among whites in Louisiana (nationwide, the average is about twice as high). And with viral load often unsuppressed, blacks progress to AIDS five times more frequently than white people, again outpacing the national average of about twice as often.

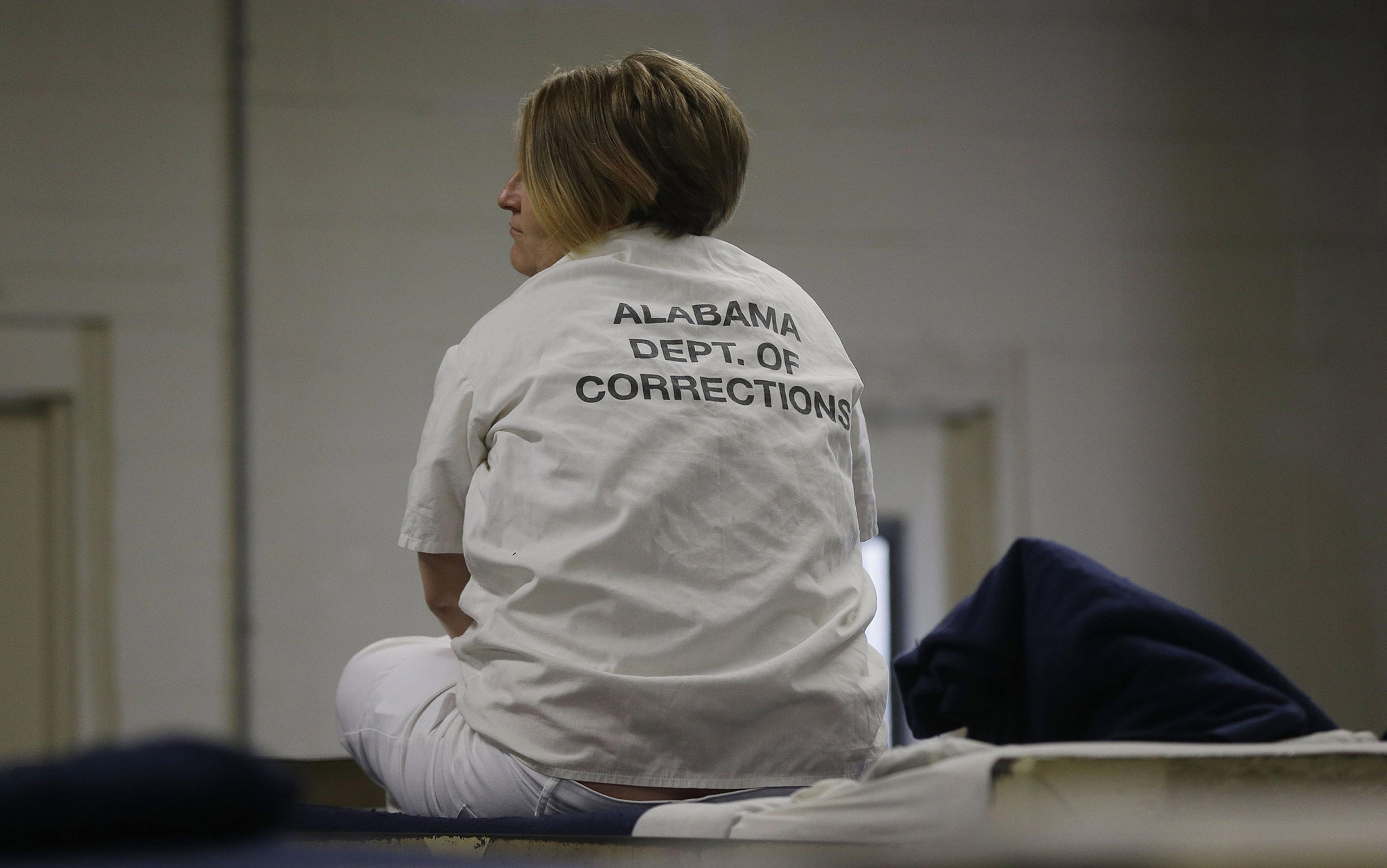

Prison also creates pathways for HIV exposure. Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate in the country, and New Orleans has the highest rate in Louisiana – this, in the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world. In New Orleans, one out of every seven black men is or has been in prison.

Jail sentences destabilise home life, which leads to multiple sexual partners, increasing the risk of HIV because so many people living with the disease are either undiagnosed or not in care, enabling viral loads to increase to dangerous levels. With fewer men left in the community, a woman can feel pressured to have unprotected sex in order to keep a man in her home. ‘There can be two to three women per man in a community,’ said Dery. ‘If one [of them] insists that he wears a condom, he’s got other options.’ Dery has several female patients who were infected through this exact scenario.

Prison is also a high-risk environment for HIV – prisoners are between five and seven times more likely to have HIV than people in the general population, increasing the likelihood that a man (or woman) will carry the virus back home.

As a result of domestic instability, and the need to make ends meet by selling sex for money, HIV is no longer so confined to one gender as it once was. The disease is now one of the leading causes of death among black women between the ages of 25 and 34 in the US – for one reason or another, these women are getting infected and then not getting tested soon enough, not getting access to care or not staying in care.

The current trajectory of Louisiana law could make matters worse. A bill that doubles the mandatory minimum from five years to ten for non-violent drug offences is currently under consideration. Possession of a narcotic drug would carry a minimum mandatory sentence of two years without parole, probation or sentencing suspension. Considering that people living in poverty are the most likely to turn to drug-related crimes to make money, these laws serve only to widen the tributary for HIV carved by imprisonment.

Knowledge about HIV is hard to come by in Louisiana. The state allows but does not require sexual education in public schools. The current law forbids education on ‘practices in human sexuality’ – meaning heterosexual or homosexual intercourse – and requires that abstinence outside of marriage be emphasized. The policy is in part a relic of programs begun during Ronald Reagan’s presidency; the budget allotted to these programs swelled to $175 million under George W Bush. For poor, struggling states, adhering to abstinence-focused sex education was an easy way to increase the annual budget. In 2010, Louisiana received almost $1 million in such funds. In May of 2014, a bill that would have repealed the current law and instead required sex education in public schools with contraception instruction was struck down by the State legislators for the third year in a row.

Without knowledge of how to protect themselves from HIV during sex, sexually active teenagers are left exposed. In 2011, people between the ages of 13 and 24 accounted for 25 per cent of all new HIV cases in Louisiana. ‘Youth don’t learn not only how their bodies work but also how to protect their bodies,’ said Bowen.

Mardi Gras was a week before my visit to New Orleans. In her office, overlooking a low-income neighbourhood claimed by eminent domain (compulsory purchase) to make way for the new hospitals, Bowen recalled seeing a parade float from a high school. The teenagers were playing instruments and celebrating, but Bowen could only feel haunted by the facts. ‘That high school has a huge prevalence of HIV,’ she thought.

Bowen, a slender white woman from far northern New York, told me more about the school and its community – that it is predominantly black and low-income, and that even when several adults combine their resources under one roof, families still struggle to pay the water bill. Violence on the streets is an everyday reality for the young people living there. ‘All of those issues related to just trying to survive make it so difficult to get that prevention and that treatment message really heard.’ Without prevention, HIV spreads from one person to the next. Without treatment, viral loads increase, rendering the hosts increasingly contagious. And as the untamed virus mutates from form to form, drugs that would otherwise suppress it no longer work.

Poverty was one motive for adopting an abstinence-only policy, but entrenched conservatism was another. The programmes remain, along with other efforts to legislate morality in the state. In 2011, Louisiana Family Forum, a powerful lobby group, successfully fought a bill that would have prevented government agencies from discriminating against sexual orientation when hiring new employees. Bias against homosexuality makes both men and women reluctant to get tested, because a positive result is seen as a sure sign of being gay. ‘The number of times I’ve heard someone say, “I don’t want to get a test because I don’t want to know my status”,’ Bowen said. She told me about a client whose family made him use a paper plate and plastic fork at a holiday meal, instead of regular dishes like everyone else.

Community support is often not strong enough to overcome the stigma. ‘If your clergy is calling it an act of sin and the reason you got this an act of God, how do we make it something you don’t have to be ashamed of?’ asked Deon Haywood, executive director of Women With a Vision, a non-profit organisation dedicated to improving the lives of black women in New Orleans.

The state does little to support those who suffer from discrimination and shame. HIV criminalisation laws, which make it illegal for an infected individual to spit at someone else, remain on the books in Louisiana despite factual knowledge about how the virus is transmitted. In the temporary office of Women With a Vision – their original location was destroyed in a fire probably caused by arson – Haywood told me about an HIV-positive woman who, in 2013, was arrested for scratching her boyfriend after she’d called the police because he was hitting her. ‘It became all about her trying to infect not only her boyfriend but also them,’ said Haywood. ‘If people are going to be criminalised for being positive, why would they tell?’

Even when people in high-risk situations try to protect themselves, Louisiana policies get in the way. In New Orleans, carrying a condom is considered grounds for suspicion of being an illegal sex worker. In a recent Human Rights Watch report documenting the city’s violations against sex workers, 44 of 169 survey respondents said they’d been harassed by the police for carrying condoms. Fifty-eight said they carried fewer condoms out of fear of such problems, and 48 had unprotected sex as a result.

All of this – the cultural stigma and resulting shame, the legalised discrimination – creates an ideal situation for the virus. The more disincentive there is to being tested, the more likely it is that viral loads will to rise to dangerous levels. The harder it is for people to adhere to care, the easier it is for the virus to colonise the host and spread.

Then there is the drug scene. Drug users, who constitute about 11 per cent of people infected with HIV in New Orleans and about 16 per cent of AIDS patients there, are also legally prevented from protecting themselves. The CDC and the World Health Organization both recommend syringe exchange programmes so users can obtain clean needles. Louisiana has one such programme, open for two hours every Friday, along with a few volunteer-run, underground syringe exchanges.

Among those infected with HIV, drug users progress to AIDS the fastest, experience complications fastest, and die the soonest

Some US states have eliminated syringes from drug paraphernalia laws, but Louisiana is not among them. Possession of a needle for non-medical purposes is a crime, and users can be charged with possession, whether or not they have drugs on them. The paucity of clean needles and danger of being caught carrying one lead drug users to share needles, creating yet another opportunity for HIV to spread. ‘Injection drug use pulls out a ton of virus and puts it right into the bloodstream,’ Dery tells his medical students.

For various reasons – lack of access, lack of availability, lack of affordability – drug abusers wishing to quit are not finding their way to rehab. ‘Black women who use drugs, struggling with addiction, don’t get the option to go to treatment,’ said Haywood. ‘You get jail time.’ Among those infected with HIV, drug users progress to AIDS the fastest – nearly half develop the condition within six months of diagnosis – experience complications fastest, and die the soonest.

On a Friday morning, the loveliness of the French Quarter is resurrected once again after the previous night’s partying. Flowers in full bloom climb metalwork terraces that sparkle in the sunlight. The narrow streets hide inviting side alleys and cafés. The whole town is irrepressibly festive almost constantly. And so it is with those seeking to halt the spread of HIV – the urge to resurrect the city’s health from the mess of social conditions that feed the disease is present everywhere.

At Women With a Vision, Haywood and others are turning their attention to the people behind the shame-inducing stigmas, not just the women who suffer. ‘We won’t call people “victims”,’ she said. And they are pushing the police and courts to use the term ‘sex worker’ instead of ‘prostitute’ because, she explained, ‘that term is more respectful and acknowledging that a lot of it is attached to work.’

Although not an advocacy organisation, NORAPC is working for Medicaid expansion to ensure access to care, mandatory comprehensive sex education, decriminalising HIV and increasing the availability of affordable housing. ‘Reducing stigma is embedded with each of those,’ Bowen said. New Orleans is home to at least 18 separate organisations dedicated to addressing the HIV epidemic.

Dery, who plays upright bass in a rockabilly band and rides a Mardi Gras float with a group of Elvis super-fans, is using music to reach those at risk. He plans an annual HIV Awareness Music Project, a day dedicated to raising awareness about testing and treatment. He has also started a radio station called WHIV, devoted to social justice writ large –though he thinks that just the station name alone can make a difference.

These are broad-stroke measures compared with Dery’s work on the ground. Twice a week, at a community clinic on the outskirts of the city, he sees patients and treats the disease.

One patient – a 25-year-old gay black man serving in the military who was infected with HIV by a boyfriend who failed to disclose his status – told Dery he wanted to start a family. Dery responded without hesitation: ‘How do you want to make that happen?’ The man told him a friend would carry the baby. Dery told his patient – again, no hesitation – that as long as his viral load remained undetectable, he had almost no transmission risk. He mentioned a doctor he knew of who scrubbed the virus from semen, and suggested he look into whether military insurance would cover any part of the procedure. There was no judgment and no shame. ‘A lot of what I do is try to help remove the stigma attached to HIV,’ Dery told me.

Hurricane Katrina, a devastating storm worsened by inadequate attention to the levees walling the city in from the coast, is never far from anyone’s mind in New Orleans. Everyone I meet points to a mark on some building indicating how high the floodwaters reached. Dery keeps a stash of unused prescriptions at his clinic and his home in case any of his patients should run out of medication during the next storm.

But the next natural disaster has already arrived in Louisiana. Collapsed social structures have flooded the state with a sickness fuelled by poverty and shame. The failed levees of protection, early testing, and accessing and adhering to care have allowed viral loads to rise and the pathogen to spread. The question now is whether these structures will be repaired before the epidemic gets worse.