In 1952, John Cage shocked audiences by staging four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. His composition 4’33” was an attempt to make nothing audible. It was inspired in part by Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings (1951), entirely white canvasses that work as blank screens to register shifting shadows and reflections, and project them as art. ‘A canvas is never empty,’ says Cage, quoting Rauschenberg, and 4’33” bears that out, as random ambient sound – coughing, shifting, programmes rustling – becomes a kind of music. These works illustrate the impossibility of saying nothing: to represent nothing is to negate it by turning it into something – an image, a piece of music, a reflection of and on movement, time and change.

Cage explores this conundrum in his ‘Lecture on Nothing’ (1959). The essay includes this self-refuting statement:

I have nothing to say

and I am saying it and that is

poetry as I need it .

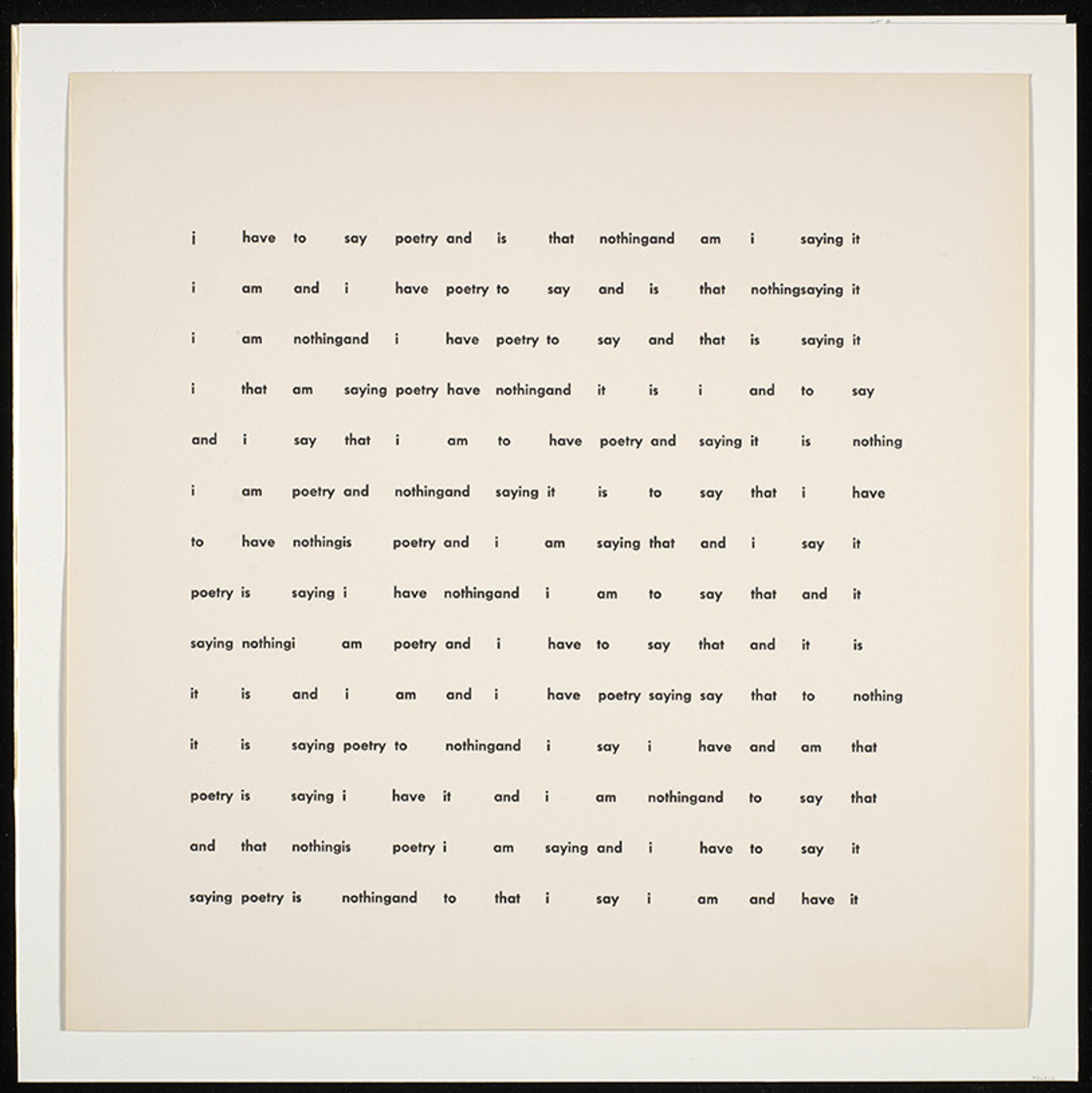

Like the negative space against which words become visible (voids emphasised in Cage’s original typography), nothing generates speech and the speaker, poetry and the ‘I’ who needs it. The Scottish poet Edwin Morgan develops this idea in his hypnotic sonnet ‘Opening the Cage’ (1966) which offers 14 variations on Cage’s 14-word sentence. For Morgan, as for Cage, saying nothing is a paradoxical gesture of creative and even existential affirmation:

Poetry is saying I have it and I am nothing and to say that

And that nothing is poetry I am saying and I have to say it

Saying poetry is nothing and to that I say I am and have it

opening the cage: 14 variations on 14 words - i have nothing to say and i am saying it and that is poetry (john cage) (1966) by Edwin Morgan (1920-2010), part of Concrete Poetry Britain Canada United States. Used with the permission of the Edwin Morgan Trust. Photo by Tate Gallery, London

Is there a way to speak or even to think of nothing without making it something, betraying its character as nonexistent? The idea of nothing pushes at the limits of thought and language, demanding new modes of analysis and expression. Moreover, if nothing is something, that would seem to complicate the definition of ‘something’ as an entity that really exists in the world. And if it is not something, then what ‘is’ it? A paradoxical question if there ever was one. More than just a linguistic puzzle, the idea that ‘nothing exists’ challenges our understanding of existence itself and spurs more nuanced theories of reality. To speak of nothing raises questions about everything. One can see why philosophers and artists alike have been drawn to it.

The history of nothing in Western philosophy is long and varied. Philosophers have distinguished between different kinds of nothing (what is not absolutely, not a specific something, not real, etc): its vagueness is part of the fecundity of the concept. They have treated it as a problem of theology (the heretical idea that everything may come not from God, but from nothing); of ethics (for Jean-Paul Sartre, nothingness is the precondition of human freedom); and of logic, as when Bertrand Russell scandalously conceded the logical existence of negative facts.

Above all, speaking nothing has been a problem of ontology, the systematic discourse (logos in ancient Greek) of beings (onta) and of being (on). Ontology is the study not of this or that particular being but of being in general: not just every material and conceptual entity in the world but the essence (from the Latin esse, ‘to be’) that unites them all and allows us to say of each one that it ‘is’. Ontology asks: what actually exists and how do we know? An investigation of fundamental reality, it also opens onto questions about language and thought and their access to (or obstruction of) that reality – that is, the relation between logos and onta. Thus, Aristotle dubbed the enquiry into being ‘the first philosophy’ and considered ontological questions the prerequisite for philosophy as a whole. Those questions have taken on new life today as physicists ponder the indeterminate ontology of the atom and cosmologists debate how something – in fact, everything – could have first emerged from nothing.

Gorgias deploys the ironies of nothing to build a counterintuitive (and frankly dodgy) case against anything

As this last question suggests, being is often defined in relation to its opposite, and the study of being almost necessarily entails the study of nothing. But what is the status of nothing in ontological enquiry? Does it belong to logos or to onta? Is it a problem of saying (as Cage articulates it) or of being (as G W F Hegel has it, for whom being at its most absolute is indistinguishable from nothing)? Does it represent the limits of human expression or a negativity within the structure of reality itself? Ludwig Wittgenstein raises this question in the final (Cage-like) aphorism of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921): ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.’ Philosophy’s ultimate object is a being – or is it a nonbeing? – inaccessible to logos and a truth that can be spoken only through structured silence.

Ontology’s fascination with nothing and its relation to both terms – onta and logos – goes back to the ancient Greeks. The sophist Gorgias (483-375 BCE) wrote an entire treatise on it. His ‘On Nonbeing’ proposes that ‘nothing exists; that if something does exist it is unknowable; and if it exists and is knowable, it cannot be communicated to others.’ Through a series of brain-teasing syllogisms, he deploys the ironies of nothing to build a counterintuitive (and frankly dodgy) case against anything, on the premise that, since being and nonbeing are opposites, if nonbeing exists – as it does, as soon as we speak it – then being must not. Sliding between two senses of the phrase ‘nothing exists’, Gorgias’ claim would seem to be refuted by the very logos that asserts it, a logos that survives, albeit only in paraphrases and scattered quotations, to this day.

How does one speak of nothing without turning it into something, rendering one’s own logos self-negating and nonsensical? As the Eleatic stranger puts it in Plato’s Sophist, to speak of nonbeing is not only to say nothing but not to speak at all – which he will continue to do for many pages in arguing dialectically for the existence of nonbeing and the possibility of naming it. To speak of nothing strains against the very raison d’être of language. It is no wonder that for the ancient Greeks ouden legein (‘to say nothing’) meant to talk nonsense.

Gorgias and Plato were both responding to the first ontologist, Parmenides, who lived in Elea in Greek-speaking southern Italy in the late 6th to early 5th century BCE. Earlier thinkers had meditated on the nature of particular beings – humans, gods, etc – but Parmenides was the first to explicitly take on being itself. In the process (and almost against his will), he also speaks of nonbeing. Parmenides illustrates the perplexities nothing poses for ontology and the poetic and philosophical creativity these generate. He also suggests the stakes. For Cage and Rauschenberg, nothing is a negative space that foregrounds the coughs and shuffles of everyday existence. For Parmenides, by contrast, the denial of nothing secures being in the abstract, but at the cost of repudiating life itself, the experience of being alive in the world.

Parmenides’ fragmentary epic poem On Nature traces the journey of a philosophical initiate under the guidance of an unnamed goddess. The goddess leads ‘the young man’ (as he is called) away from the way of Doxa (Opinion), the world we live in and our deluded beliefs about it. This is a world of transient phenomena (objects and appearances – the Greek word phainomena signifies both) and the ambiguous names we give them: ‘there will be a name (onoma) for all things, as many as mortals have established, believing them to be true: to be born and perish, to be and not to be, to change place and to alter their bright colour.’

Leaving this unstable world of appearances, the young man ascends the path of Alētheia (Truth) that leads to being. In contrast to the impermanent objects of human language and belief, being is ‘ungenerated and indestructible, whole-limbed and untrembling and without end’. Compared with a perfect sphere, it is unitary and homogenous, eternal and unchanging. This great orb of presence Parmenides names – with stunning simplicity – ‘being’ (eon) or, more simply still, ‘is’ (esti). He makes unprecedented use of the participial form (eon in his dialect) and the third-person present indicative (esti) of the verb ‘to be’ (einai) to create new names for a new concept. The verb in these forms has no subject: it is being without a specific be-er, abstract and absolute ‘is-ness’.

With this verbal innovation, Parmenides in effect invents ontology, positing not only being but also the possibility of a logos about it. The Greek verb einai conjoins a notion of reality and of true claims about it: ‘Socrates is [ie, exists]’ and ‘Socrates is an Athenian.’ Parmenides’ esti in itself thus affirms an ideal correspondence between language and reality, the thesis that ‘to speak (legein) and to think are necessarily “being” (eon), for “to be” is (einai esti) and nothing is not.’ In these difficult (and much disputed) lines, he unites language and being: we can access reality through speech, and that speech (legein, the verb that gives us logos) partakes of reality. Esti encapsulates that union, collapsing what exists and what can be said about it into a single word. ‘Is’ is – a pure and perfect logos of on.

‘Is not’ is not only the road not taken: it is not even a road at all

Parmenides constructs and secures this ontology through the rigorous elimination of nonbeing: ‘for “to be” is and nothing is not’ (mēden d’ ouk estin). Nonbeing is a persistent but repudiated (non)presence in the poem and a problematic – and generative – (non)element in Parmenides’ philosophy. Esti is necessarily thinkable and speakable: ‘that “is” (estin) and cannot “not be” (mē einai) is the path of conviction, for she attends Truth.’ ‘Is not,’ by contrast, ‘is a path that cannot be learned, for you could not know what is not (for that is impossible) nor could you speak it.’ These two ‘paths’ are ‘the only routes of enquiry for thinking’, and the choice between them is the philosopher’s first and most critical step: ‘the choice (krisis) concerning these things lies in this: “is” or “is not”.’ This is not a personal choice like Hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be’, but something more absolute and basic: an alternative between being – a definite, permanent reality that we can think and talk about – and an unspeakable, unthinkable nothing.

Our failure to grasp this alternative is what makes the mortal realm of Doxa so untrustworthy. We humans are ‘uncritical (akrita) races, by whom “to be” and “not to be” are considered the same and not the same, and the path of all things is backward-turning.’ Thus we mistake ephemeral phenomena for real beings. For example, we may say that ‘the Moon is’. But the Moon waxes and wanes; it goes by different names and even disappears from view. Since it once came into existence (whether we explain that mythologically or scientifically), it didn’t always exist. So when we say ‘the Moon is’ we conflate ‘is’ and ‘is not’: we use only partially true language about an only provisionally existent thing. We adulterate being with nonbeing.

Parmenides’ strict division between ‘is’ and ‘is not’ underwrites a division between everyday appearances and true being. As Friedrich Nietzsche would later charge, Parmenides’ division is the first chapter in a long history of philosophical denigration of empirical reality and lived experience. That Parmenides himself was not entirely numb to the sacrifice involved is suggested by his luminous description of the Moon as ‘a night-shining alien light wandering around the Earth’.

Parmenides’ goddess saves us from the confusion of Doxa by barring the path to ‘is not’: ‘It has been decided,’ she says, ‘to leave the one route [“is not”] unthought and unnamed, for it is not a true route, while the other one both is and is true.’ ‘Is not’ is not only the road not taken: it is not even a road at all. It is simultaneously forbidden and declared nonexistent. But if it doesn’t exist, why must it be forbidden? And if it is unthinkable, why must we be persuaded not to think about it? If nonbeing simply were not (in the same way that ‘is’ is), there would be no need for Parmenides’ goddess to direct us away from it. Indeed, there would be no need for Parmenides’ poem at all. To that extent, nonbeing is the necessary underpinning of his poem and of his entire philosophical project.

In fact, for something that is unspeakable, nonbeing is spoken of with surprising frequency in the extant fragments. Not only is nonbeing not left by the wayside in the ascent to being, but ‘is’ seems to require ‘is not’ in order to secure its existence and nature – its very being. We are told, for instance, that being must be eternal and ungenerated, because what could it have been generated from? ‘Not from nonbeing,’ the goddess insists. ‘I will not allow you to say or to think that, for it cannot be said or thought that “is not”.’ The idea that being was generated – that it came into being at some specific point in time – is anathema to Parmenides because it implies that there was a time when being was not. But even as the goddess prohibits the thought, her very insistence invites us to contemplate this forbidden genesis and its consequences: that being is the child of nonbeing and carries that origin as part of its identity.

Likewise, we are told that being is a bounded sphere of unadulterated presence beyond which is nothing but a vast inconceivable nothing. Being must be bounded in order to have a definable identity, but that identity is, as a result, defined by the nonbeing beyond it (a paradox Hegel would term ‘determinate negation’). It is like an island marked out by the dark sea around it.

‘Is’ therefore needs ‘is not’ and Parmenides’ language paradoxically preserves that ‘is not’ in the very process of eliminating it. When he writes ouden gar [ē] estin ē estai allo parex tou eontos, we can translate it as either ‘there is or will be nothing else outside of being’ or ‘nothing is or will be, something else outside of being.’ Nothing persists in the very logos that works to negate it, and that logos is a part of the poem no less than the singular perfect word of being, ‘is’. Parmenides has to say nothing, and saying it is ‘poetry as he needs it’.

If Parmenides must say nothing, even against his will, Democritus proclaims it an explicit and foundational element of his ontology. Writing a century after Parmenides (c460-370 BCE), Democritus developed the atomic theory first proposed by his teacher Leucippus. Virtually no fragments of Leucippus remain, and atomic theory is known mostly through later paraphrases of Democritus, particularly by Aristotle and commentators on him.

The atomists adopted Parmenides’ conception of being as singular and unchanging, but they attempted to reconcile this with the empirical experience of plurality and change. First, they pluralised Parmenides’ eon in the form of the atom, those ‘little beings boundless in number’ (as Aristotle calls them in a lost work on Democritus). Like Parmenidean being, atoms are eternal: they neither come to be nor pass away. Unlike Parmenides’ monadic being, they are infinite in number and diverse in shape and size. Joining and separating, they produce the Universe and all the things in it.

Second, the atomists asserted the existence of nothing in the form of the void. ‘An interval in which there is no perceptible body,’ as Aristotle put it in the Physics, the void separates one atom from another, sustaining its atomic identity; it also provides the physical vacuity (kenon) in which atoms travel, combine and separate. Like the blank spaces in Cage’s typography, the void is a negative space that highlights the positive presence of the atom and enables its life-giving motion. But that empty space also has a positive presence since, for the atomists, ‘the void exists’, as Aristotle says in On Generation and Corruption.

If the void is the absence of an atom, the atom exists as what fills a void

By asserting the contradictory existence of nothing, the atomists reconcile being and becoming, the absolute ‘is’ of Parmenides’ path of Truth and the illusory human world of his Doxa, and give a new status to the latter. On the one hand, as a temporary aggregation of atoms, the phenomenal world is epiphenomenal or second-order, as Democritus says in his most famous fragment: ‘By convention sweet and by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention colour, but in reality atoms and void.’ Like Parmenides, Democritus differentiates between the pseudo-being of human experience and the true reality that lies beyond it. On the other hand, since phenomena and their qualities are nothing but the effect of atomic interactions, they are intrinsically tied to that deeper reality: for the atomists ‘what appears (phainomenon) is what is true,’ as Aristotle complains in On the Soul. It is little surprise that Nietzsche, who considers Parmenides’ being the rigor mortis of life itself, was a fan of Democritus.

The atomists’ ontology thus seems to make space (as it were) for nothing in a way that Parmenides refused to do. In proclaiming the existence of nothing, however, Democritus turns it into a quasi-something, a positive entity, real enough to hold atoms apart, though not to impede their motion. The result is an oddly relative ontology. In contrast to Parmenides’ absolute dichotomy between ‘is’ and ‘is not’, the atomists, according to Aristotle’s Metaphysics, ‘say that “what is” exists no more than “what is not” because the void exists no less than the body,’ that is, the atom. Being and nonbeing are comparative, like their synonyms full (plēres) and empty (kenon). This comparative relation makes being itself relative, and relative, moreover, precisely to nonbeing. If the void is the absence of an atom, the atom exists as what fills a void. Being starts to look, as the Franco-German philosopher Heinz Wismann puts it, like ‘a privative state of nonbeing, its positivity just a lure.’ (My translation.)

The Greek language has a precise vocabulary for being and nonbeing, as we saw with Parmenides. That vocabulary, in Greek as in English, figures the two as mutually exclusive opposites: nonbeing (the word and the state) negates being (the word and the state). Democritus imagines a more intimate and entangled relation between the two states. To express this, he invents a new word: ‘den’. One of Democritus’ names for the atom, this word is created from nothing twice over. ‘Democritus declared that the den exists (einai) no more than the mēden (nothing), calling the body den and the void mēden on the grounds that the latter too has a certain nature and its own existence,’ says Plutarch in Against Colotes. Plutarch suggests that the den is a consequence of the existence of void. It is logically derivative of nothing and defined by it: it ‘is’ (einai) no more than nothing. It is not only logically but also etymologically derivative. Den is a neologism formed from mēden, ‘nothing’, which was itself originally a combination of the negative adverb mēde (‘not even’) and the adjective hen, ‘one’. Den is produced by a false division of mēden such that the de, originally part of the negation, is treated as if it were part of the adjective hen. That is, instead of mēd-en, ‘nothing’ is erroneously parsed as mē-den. Translators trying to render the term in English have proposed ‘’othing’.

Aristotle and other ancient commentators treat the den as a simple synonym for the atom conceived as a nugget of pure Parmenidean being. But the French philosopher Barbara Cassin argues that den names a fundamentally different kind of being from Parmenides’ eon. While the latter is ungenerated and undying, with the den, being comes into being as an incomplete subtraction from nonbeing (the erasure of the initial mē): it is literally less than nothing. Logically dependent on nonbeing, being is no longer autonomous and self-grounding as it was for Parmenides; nor is it pure and homogeneous, for the d’ of den preserves a remnant of mēden within it. Nothing splits the atom. With the den, Democritus builds negativity into the very heart of his physics and metaphysics: nothing lurks within something.

Democritus announces a new ontology, one that encompasses not only ‘is’ but also ‘is not’

Democritus’ den solves – or at least circumvents – the quandary of how to speak about nothing. Den says nothing precisely by not saying it: the d’ signifies nonbeing as an absence – the barest remnant of an incomplete erasure – within being. As far as we can tell from the fragmentary remains of his work, Democritus never elaborated on the concept of the den or offered a full account of it. Democritus presents his atomic theory as totalising, ‘a logos concerning all things’ that describes reality in its entirety. But within this exhaustive logos, one thing remains unspoken: the den. Democritus invents the word but cannot – or does not – theorise it. In this way he preserves nothing and builds it into his theory of everything: he neither eliminates it as unthinkable and unspeakable (as Parmenides had) nor turns it into a positive entity (as he does with void, ‘for the void exists’). Instead, the den speaks mutely, a silent nonpresence within a theory of presence, a troubling hole within a universal logos and a shadowy nonbeing within being itself. Democritus has (n)othing to say and he is saying it.

The den illustrates again the fecundity of nothing. With the den, Democritus not only invents a new word but announces a new ontology, one that encompasses not only ‘is’ but also ‘is not’ and – more radically – something (or nothing, or ’othing) that somehow combines the two. This is an idea that we are only starting to come to grips with today, as philosophers think through the implications of quantum physics. The atom has been shown to be a profoundly indeterminate being: at once particle and wave, there and not there, something and nothing. Meanwhile, the science of quantum vacuum is cashing out Democritus’ intuitions about the void, in the process spurring new experiments and new theories. Nothing is as paradoxically productive for physics as it has been for philosophy and art. It may even have produced the Universe itself, as Lawrence M Krauss hypothesises in A Universe from Nothing (2012), as quantum fluctuations of empty space spontaneously generated the virtual particles that gave rise to matter – as if Rauschenberg’s blank canvasses themselves created the shadows they reflect and the objects that cast them. Everything is born of nothing and, if the physicists are right, will some day be consumed by this expanding nothing. And that, we might say, is poetry as we need it.