In 1927, Virginia Woolf, perusing a dummy copy of her latest book To the Lighthouse – its pages utterly blank – pronounced it ‘the best novel I have ever written’. She was only half in jest, knowing very well that the dummy’s empty pages would be perfectly legible to Vita Sackville-West, to whom this inscription on the flyleaf was addressed. Vita was bound to pick up on what went without saying yet could not be expressed publicly: Woolf’s longing for her.

We might draw a more general feminist reading from this private joke between lovers. As the literary critic Susan Gubar observed in 1981:

While male writers like Mallarmé and Melville also explored their creative dilemmas through the trope of the blank page, female authors exploit it to expose how woman has been defined symbolically in the patriarchy as a tabula rasa, a lack, a negation, an absence.

In Technologies of Gender (1987), Teresa de Lauretis says the virginal ‘blank page awaiting insemination by the writer’s pen’ is a ‘notorious cliché of Western literary writing’. Woolf might have had all this in mind too, but what if we were to take her statement at face value? What if these blank pages were the best novel she’d ever written? Or even the best novel she could ever write – one that could be conceived of but never realised?

In 1975, the Mexican conceptual artist Ulises Carrión declared: ‘The most beautiful and perfect book in the world is a book with only blank pages, in the same way that the most complete language is that which lies beyond all that the words of a man can say.’ Unlike Woolf, he was not joking. He was alluding to what gets lost, somewhere between conception and execution: to the impossibility of faithfully translating the work in your mind into the work on the page. This is why the critic George Steiner in 1984 defined ‘a serious book’ as ‘one which should have been better’ – a sentiment echoed by most writers worth their salt, every book being ‘the death mask of its conception’ (Walter Benjamin); ‘the wreck of a perfect idea’ (Iris Murdoch); ‘a betrayal of all perfection’ (David Foster Wallace); ‘a bad, ridiculous copy of what you had imagined’ (Thomas Bernhard).

If all works of literature are haunted by the ideal forms of which they are but imperfect instantiations, then the blank book – as envisaged by Carrión – symbolises the refusal to compromise authorial vision.

The most famous blank pages in literary history must be those in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759-67), particularly the one that invites readers to doodle their own portrait of the sultry Widow Wadman: ‘Sit down, Sir, paint her to your own mind – as like your mistress as you can – as unlike your wife as your conscience will let you …’ In Sterne’s vivid imagination, the blank page was a place to let fantasy run riot while undermining the author’s own authority and highlighting fiction’s troubling lack of necessity. In fact, blank books are said to have featured in Eastern legends for centuries, but – Sterne notwithstanding – they appeared on bookshelves only in the 20th century.

The poet and artist Michael Gibbs’s anthology of blank books All or Nothing (2005) includes extracts from 23 partly or totally blank publications, although the lengthy introduction mentions many more besides. All the excerpts are identically void of text, save for the title, publication date and author’s name tucked away discreetly at the foot of each verso. Most are avant-garde artistic or poetic experiments, often tinged with mystical or philosophical influences.

The blank page and blank canvas constantly oscillate between these two polar opposites

A dearth of quality submissions prompted the almost entirely empty issue of The Little Review, published in September 1916. With titles such as The Wit and Wisdom of Spiro T Agnew (1969) or, more recently, The Wit and Wisdom of Nigel Farage (2014), political parody segues into the novelty empty-book category, exemplified by the bestselling Everything Men Know About Women (1988). There are, inevitably, omissions such as the cultish blank poetry review entitled Nudisme that featured in the opening scene of Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée (1950). In No Medium (2013) – a study of blank, silent and erased works – the poet and critic Craig Dworkin reports that a real-life version of this film prop was created by a couple of enterprising designers (‘can be used as a notebook or not,’ announced the website where it was sold).

Keeping track of this phenomenon in contemporary fiction is well nigh impossible, so I shall just mention the four blank pages in Alasdair Gray’s 1982, Janine (1984) during which the narrator is asleep, and the 40 blank (or virtually blank) pages corresponding to the protagonist’s mysterious disappearance in Evan Dara’s The Easy Chain (2008).

The oldest entry in Gibbs’s anthology is the Russian Futurist Vasilisk Gnedov’s ‘Poem of the End’ (1913), which is often presented as a prefiguration of Kazimir Malevich’s painting White on White (1918) – a blank white square on a blank white square – though Gnedov envisioned his poem as a materialisation of nothingness, whereas Malevich interpreted the blankness of his artwork as an evocation of infinity. In fact, the blank page and blank canvas constantly oscillate between these two polar opposites.

.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

White on White (2018) Kazimir Malevich. Courtesy MOMA/Wikipedia.

In his Lectures on Literature (1980), Vladimir Nabokov writes: ‘The pages are still blank, but there is a miraculous feeling of the words all being there, written in invisible ink and clamouring to become visible.’ The absence instantiated by the blank page is inherently ambiguous. Is it the absence of words as yet uncommitted to paper, hovering pre-formed, or of words that have been erased, repressed, perhaps even suppressed?

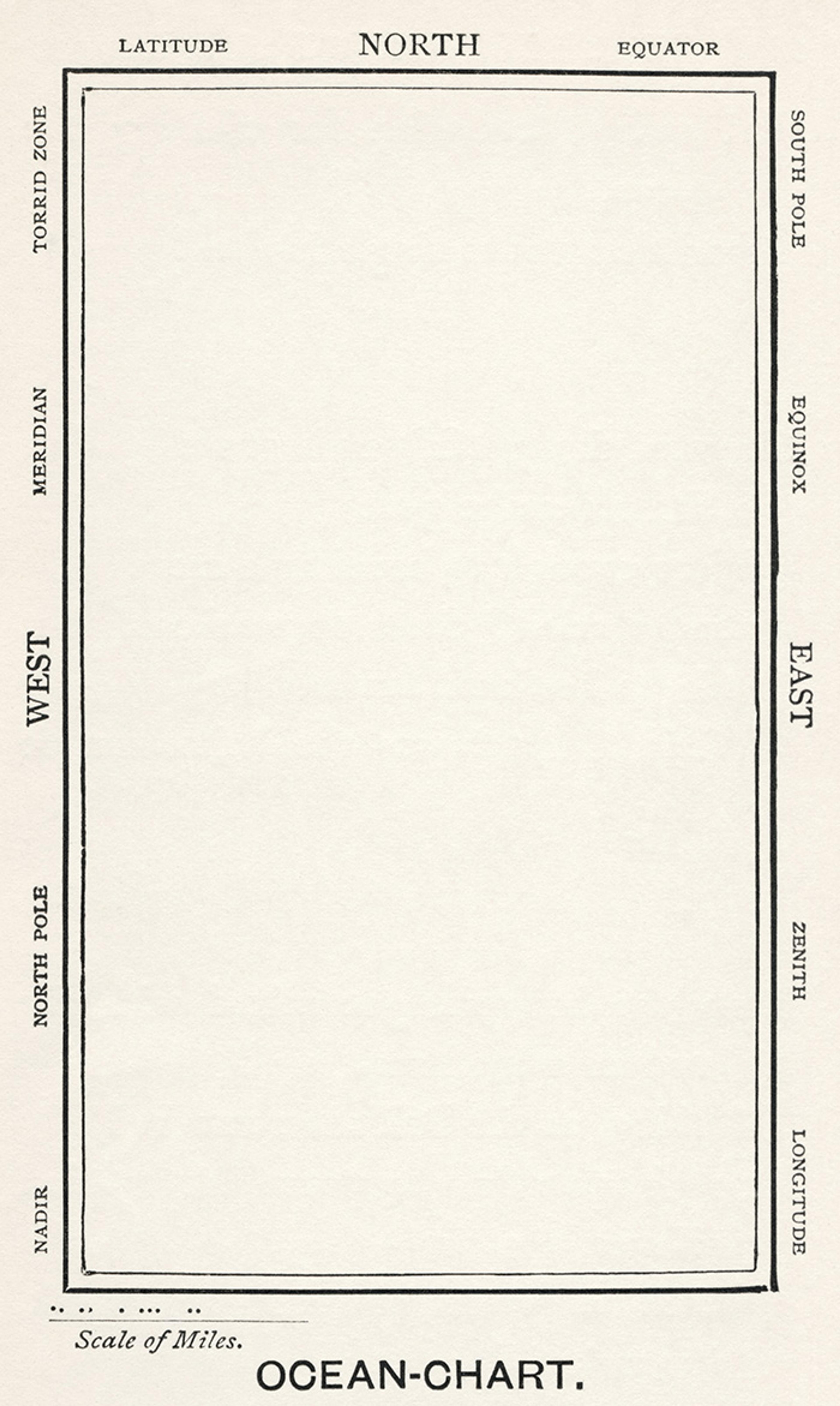

The blank chart from The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll, MacMillan and Co, Limited, St Martin’s Street, London, 1931 edition

Although usually apprehended as terra incognita – see the blank map (above) in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark (1876) – this empty space can also be construed as a chalk outline at a crime scene, marking the spot once occupied by all the authors of the past. In Nay Rather (2013), the poet Anne Carson reframes the debate once more in terms of the blank canvas:

When Francis Bacon approaches a white canvas, its empty surface is already filled with the whole history of painting up to that moment, it is a compaction of all the clichés of representation already extant in the painter’s world, in the painter’s head, in the probability of what can be done on this surface. Screens are in place making it hard to see anything but what one expects to see, hard to paint what isn’t already there.

What the French call l’angoisse de la page blanche – writer’s block – owes as much to the anxiety of influence as to the dizziness of freedom. ‘Not even an empty page is empty,’ writes Lavinia Greenlaw in Some Answers Without Questions (2021), following Michel de Certeau who, in The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), claims ‘we never write on a blank page, but always on one that has already been written on’. Rubbing out all those phantom words, as Samuel Beckett or William S Burroughs once fantasised, is not even an option, since erasure reveals as much as it effaces. As the critic Brian Dillon noted in 2006:

Erasure is never merely a matter of making things disappear: there is always some detritus strewn about in the aftermath, some bruising to the surface from which word or image has been removed, some reminder of the violence done to make the world look new again. Whether rubbed away, crossed out or reinscribed, the rejected entity has a habit of returning, ghostlike: if only in the marks that usurp its place and attest to its passing.

The blank page, always already palimpsestic, puts me in mind of 4’33” (1952), John Cage’s infamous composition in three movements, during which the musicians are instructed not to play a single note. This ostensibly mute musical piece – inspired by Robert Rauschenberg’s lively series of blank monochromes, White Paintings (1951) – points, in fact, to the impossibility of silence by letting ambient sounds come to the fore. In similar fashion, the entire history of literature shines through the blank page, like a watermark, however much the writer might long to start from scratch. One could imagine a Magritte painting of a blank book with the caption: This is not a blank book.

The blank book is bound up with the history of literary modernity, almost to the point of merging with it. In his essay ‘The Storyteller’ (1936), Benjamin identifies the ‘solitary individual’ as the ‘birthplace of the novel’ – an individual cut off from tradition, whose legitimacy derives almost exclusively from herself. Literature could now be anything – everything – the author wanted, rather than an imitation of the great masters. Yet as Søren Kierkegaard cautioned in The Sickness Unto Death (1849), since ‘more and more becomes possible’ when ‘nothing becomes actual’, there’s a danger of worshipping idealised, unrealised works.

In Julie, or the New Heloise (1761), Jean-Jacques Rousseau rhapsodised: ‘There is nothing beautiful except that which does not exist.’ John Keats, in his ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ (1819), exalted the beauty of ‘unheard’ melodies. Literature was a blank page that increasingly dreamed of remaining blank. Written books are sweet, but those unwritten are sweeter.

A tendency to regard ‘concrete expression as a decadence, a contamination’, as Mario Praz puts it in The Romantic Agony (1930), is a typically Romantic trope. It is rooted in the long philosophical and mystical tradition of apophatic thinking – thinking that seeks knowledge through negation – that goes all the way back to the pre-Socratics (influencing the likes of Schopenhauer, Dostoyevsky, Kafka and Beckett along the way). Herman Melville’s Bartleby (the character whose response to any demand is that he ‘would prefer not to’) symbolises this reluctance to bring any work into being, thereby transforming literature into a kind of negative theology in the short story ‘Bartleby, the Scrivener’ (1853).

This expansion of the unsayable … spread like a spilt bottle of correction fluid

Bartleby embodies the very potentiality of language; that is, its potential to express nothing as well as something. As the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben notes in ‘Bartleby, or On Contingency’ (1993):

As a scribe who has stopped writing, Bartleby is the extreme figure of the Nothing from which all creation derives; and at the same time, he constitutes the most implacable vindication of this Nothing as pure, absolute potentiality.

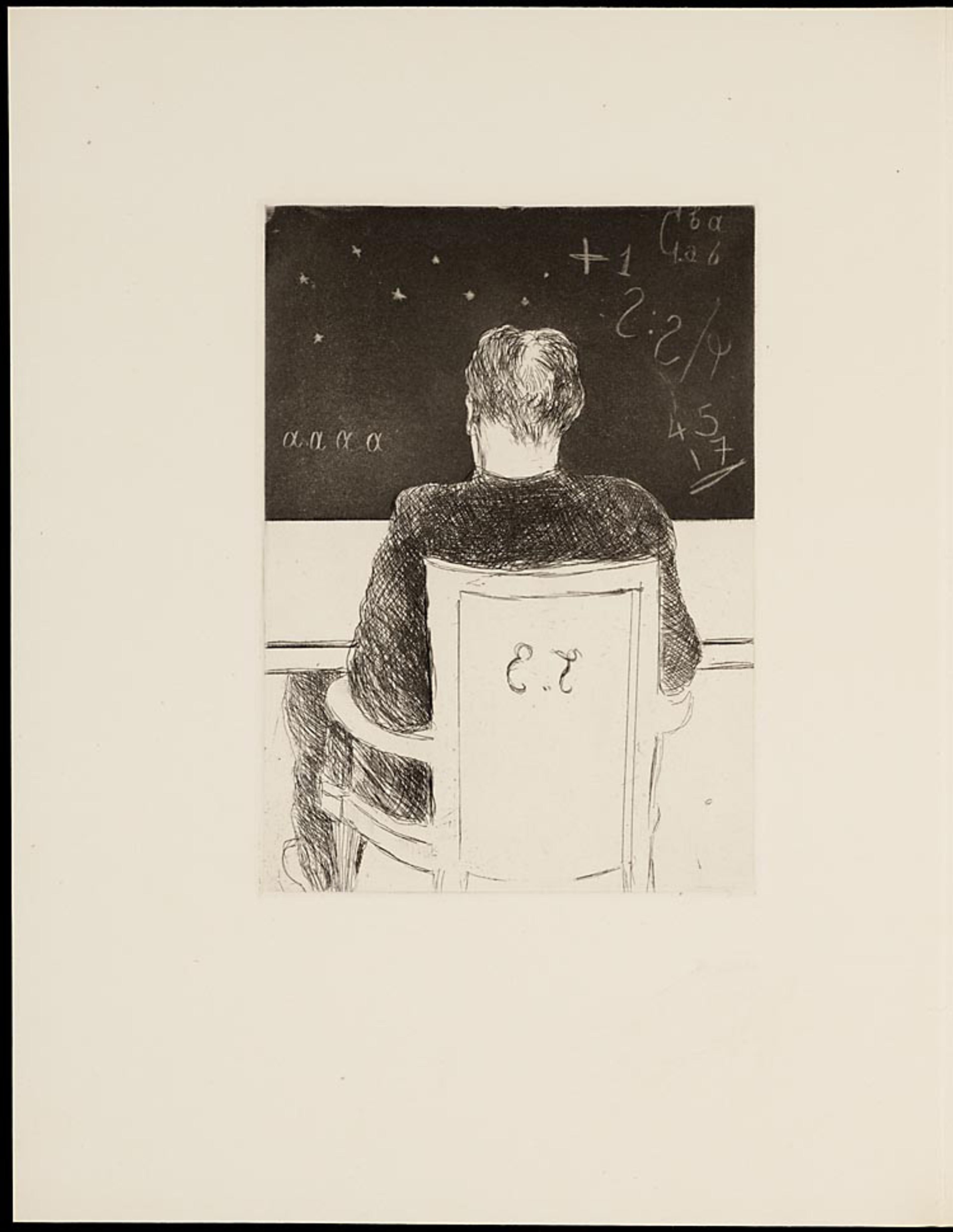

According to Steiner, the rise of the novel tracked a growing linguistic crisis. After the 17th century – after John Milton – the ‘sphere of language’ ceased to encompass most of ‘experience and reality’. Mathematics, for instance, became increasingly untranslatable into words. In the modern world, painting often inclined towards abstraction, while linguistics and philosophy highlighted the essentially arbitrary nature of signifiers. The oft-quoted final proposition in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) bears witness to this expansion of the unsayable, which spread like a spilt bottle of correction fluid: ‘Whereof one cannot speak’ – ie, what cannot be articulated meaningfully – ‘thereof one must be silent’.

Against this backdrop of declining confidence in the powers of language, literature came to be considered, in some quarters, as an absolute. For the Jena Romantics in Germany, the novel was a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, a total artwork fusing poetry and philosophy, while in England Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1821 claimed that poets were ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’. A dual historical process was set in motion, deifying authors while defying the very authority of their authorship (the power of language). In France, in particular, the modern writer was called upon to fill the spiritual vacuum left by religion’s decline. Yet as soon as this ‘solitary individual’ – no longer the mouthpiece of the gods or the muses – was elevated to the status of an alter deus, the essential belatedness, as well as arbitrariness, of human creativity became glaringly obvious. ‘No art form,’ says Steiner in Grammars of Creation (2001), ‘comes out of nothing. Always, it comes after,’ and the ‘human maker rages at his coming after, at being, forever, second to the original and originating mystery of the forming of form.’

The realisation that ‘dressing old words new’ (as Shakespeare has it in Sonnet 76) is all that writers can really aspire to didn’t always go down well. In Dadaist circles, suicide came to be seen as a response to the impossibility of bridging the gap between art and life – suicide as a form of inverted transcendence or a rejection of the reality principle, as well as a gruesome fashion. ‘You’re just a bunch of poets and I’m on the side of death,’ was Jacques Rigaut’s parting shot to the more career-minded Surrealists.

Like Rigaut, Arthur Cravan, Jacques Vaché, Boris Poplavsky, Julien Torma and René Crevel apparently all chose to make the ultimate artistic statement. Álvaro Coelho de Athayde – the 14th Baron of Teive, and one of Fernando Pessoa’s numerous heteronyms – also commits suicide after destroying all his manuscripts (save one, in which he accounts for his behaviour) in a rage about his incapacity to produce ‘superior art’. He is hobbled by perfectionism, a personality trait, but also a byproduct of the imaginative freedom enjoyed by the modern writer, which prevents him completing his books. In this, the Baron is closely related to Monsieur Teste, Paul Valéry’s alter ego, who refuses to reduce the field of possibles by actualising any of them.

An illustration drawn by Paul Valery from a 1945 edition of the Album de Monsieur Teste. They ‘are what they are: the work of an amateur’ was Valery’s judgement on his own drawings. © and courtesy the Koopman Collection/Royal Library of the Netherlands.

Both characters are clear forerunners of Robert Musil’s Ulrich – the eponymous protagonist of the novel The Man Without Qualities (1930-43) – whom the critic and novelist Maurice Blanchot describes as someone ‘who “does not say no to life, but not yet”, who, finally, acts as if the world – the world of truth – could never begin except on the next day.’ Musil’s novel is as non-committal as its protagonist, and is often deemed deliberately unfinishable as well as incomplete. Writing in The New York Review of Books in 1996, William Gass, for instance, argues that ‘Musil polished not to achieve a finish or a shine, but (like every perfectionist) to accomplish the inconclusive …’ This novel of procrastination is one response to the blank book – a means of holding literature in abeyance; of preserving part of its potentiality.

A more expeditious response to the blank book considers the writing stage as superfluous

Another response is exemplified by Arthur Rimbaud, who renounced poetry altogether after writing his Illuminations (1886) in order to become a merchant and adventurer – a ‘bourgeois trafficker’ according to Albert Camus – as well as by the fictional Lord Chandos in Hugo von Hoffmanstahl’s The Lord Chandos Letter (1902), who gives up writing and even speaking because language cannot ‘penetrate the innermost core of things’. The object of fascination, in both cases (one real, one fictitious), is that writing seems to be a necessary prolegomenon to its own abandonment and possible transcendence. ‘Because I am not silent the poems are bad,’ wrote George Oppen, the American poet who famously (but temporarily) quit poetry in the 1930s in favour of political activism.

In The Hatred of Poetry (2016), Ben Lerner recalls that:

Their [Rimbaud’s and Oppen’s] silences as much as their works – or their silences as conceptual works – were what made them heroes to the aspiring poets I knew [as a student]. It was as if writing were a stage we would pass through, as if poems were important because they could be sacrificed on the altar of poetry in order to charge our silence with poetic virtuality.

Susan Sontag, in her essay ‘The Aesthetics of Silence’ (1967), observes that the ‘choice of permanent silence’ made by the likes of Rimbaud does not ‘negate’ their work:

On the contrary, it imparts retroactively an added power and authority to what was broken off; disavowal of the work becoming a new source of its validity, a certificate of unchallengeable seriousness. That seriousness consists in not regarding art (or philosophy practised as an art form: Wittgenstein) as something whose seriousness lasts forever, an ‘end’, a permanent vehicle for spiritual ambition. The truly serious attitude is one that regards art as a ‘means’ to something that can perhaps be achieved only by abandoning art; judged more impatiently, art is a false way or (the word of the Dada artist Jacques Vaché) a stupidity.

A third, more expeditious response to the blank book considers the writing stage as superfluous. Gibbs, the editor of the All or Nothing anthology, points out that going to the trouble of actually producing such blank books ‘testifies to a faith in the ineffable’. This very same faith prompts Jorge Luis Borges to claim that ‘for a book to exist, it is sufficient that it be possible’. Even Steiner sensed that a ‘book unwritten is more than a void’. For Blanchot, the moralist and essayist Joseph Joubert was one of the first truly modern writers precisely because he saw literature as the ‘locus of a secret that should perhaps be preferred to anything else, even to the glory of making books’:

Joubert had this gift. He never wrote a book. He only prepared himself to write one, resolutely seeking the right conditions that would allow him to write … He was thus one of the first entirely modern writers, preferring the centre over the sphere, sacrificing results for the discovery of their conditions, not writing in order to add one book to another, but to make himself master of the point whence all books seemed to come, which, once found, would exempt him from writing them.

Like Joubert, Roland Barthes was less motivated by literary productivity than by the urge to uncover the conditions of novel-writing. In 1978, at the outset of his lecture series The Preparation of the Novel, he announced his intention to proceed ‘as if’ he were going to write a novel: ‘It’s therefore possible that the Novel will remain at the level of – or be exhausted and accomplished by – its Preparation.’ ‘What good is it to carry out plans,’ Charles Baudelaire had already wondered, ‘since planning itself is a sufficient delight.’ In his foreword to The Garden of Forking Paths (1941), Borges advocated synopsising books instead of writing them:

It is a laborious madness and an impoverishing one, the madness of composing vast books – setting out in 500 pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes. The better way to go about it is to pretend that those books already exist, and offer a summary, a commentary on them.

Writing to Louise Colet in 1852, Gustave Flaubert announced his ambition to write ‘a book about nothing’. He meant a novel, but one whose subject matter was inconsequential and was instead ‘held together by the internal strength of its style, just as the Earth, suspended in the void, depends on nothing external for its support.’ Whether he achieved this with Madame Bovary (1856) is a moot point, all novels being more or less about something; but what we can say for sure is that the ultimate ‘book about nothing’ is the blank book – a book that is not about anything, but simply is.

In his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 1977, Barthes describes language as inherently fascistic because it compels us to think, view things and talk in a certain manner. The world being thus always already written over, the ultimate purpose of literature, in his eyes, is not to express the inexpressible but ‘to unexpress the expressible’, as he’d written elsewhere; to take the intransitivity of writing (one of his recurring phrases) to its logical conclusion: ‘For writing to be manifest in its truth (and not in its instrumentality) it must be illegible,’ as he put it in the essay ‘Masson’s Semiography’ (1973). Illegible writing held an ongoing fascination for Barthes, all those preverbal or postverbal squiggles and doodles found in the paintings of Henri Michaux, Cy Twombly or Bernard Réquichot, for example. For Barthes, André Masson’s gestural calligraphy achieved the ‘utopia of the Text’: a world exempt from meaning, a world that would resemble a blank book – if it were truly blank.

There is also a void at the heart of language itself, which Barthes alludes to. The Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé (known for his poetics of silence and liberal use of blank space) refers to it directly when he writes that the word ‘flower’ conjures up ‘the one absent from every bouquet’. This notion that language is murder, that it negates things in their singularity, replacing them with concepts, would be refined by the Russian-born philosopher Alexandre Kojève. His idiosyncratic lectures on Hegel influenced many writers and intellectuals in 1930s France, not least Blanchot, who declared: ‘The word is the absence of that being, its nothingness, what is left of it when it has lost being – the very fact that it does not exist.’

Simply put, words give us the world. They allow us to manipulate and act upon it by taking it away. For Blanchot, however, literature takes linguistic negation one step further, by negating both the real thing and its surrogate concept. As a result, words no longer refer primarily to ideas, but to other words: they become present, like the things they negated in the first place. Literature is our secret weapon against the void at the heart of language. As Blanchot says, ‘happily language is a thing: it is a written thing, a bit of bark, a sliver of rock, a fragment of clay in which the reality of the earth continues to exist.’