The life of Walter Benjamin came to an end in late September 1940 in a small town called Portbou on the border between France and Spain. And it was Benjamin who decided to end it.

It is surely strange to think that one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century, and a man associated with two of the major capital cities of Europe, should find himself constrained to make such a choice, or rather to endure his destiny, in a place so marginal and remote.

When I write that he was one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century I am certainly not exaggerating, though I feel I should add another qualifying adjective to define him: European, because if there is a man who thought of himself as being so, in those years when Europe was only a geographical term, it was undoubtedly Benjamin; pushed to move from one nation to another, not only by events and because he was a Jew and therefore subject to persecution, but also on account of his interests and restless curiosity.

Born in Charlottenburg in Germany in 1892, Benjamin was forced to move to France after the Nazis came to power. Its capital city became a kind of second homeland for him, and the site of his intellectual passions – to the extent that one of his major works, the unfinished The Arcades Project, would be entirely devoted to 19th-century Paris.

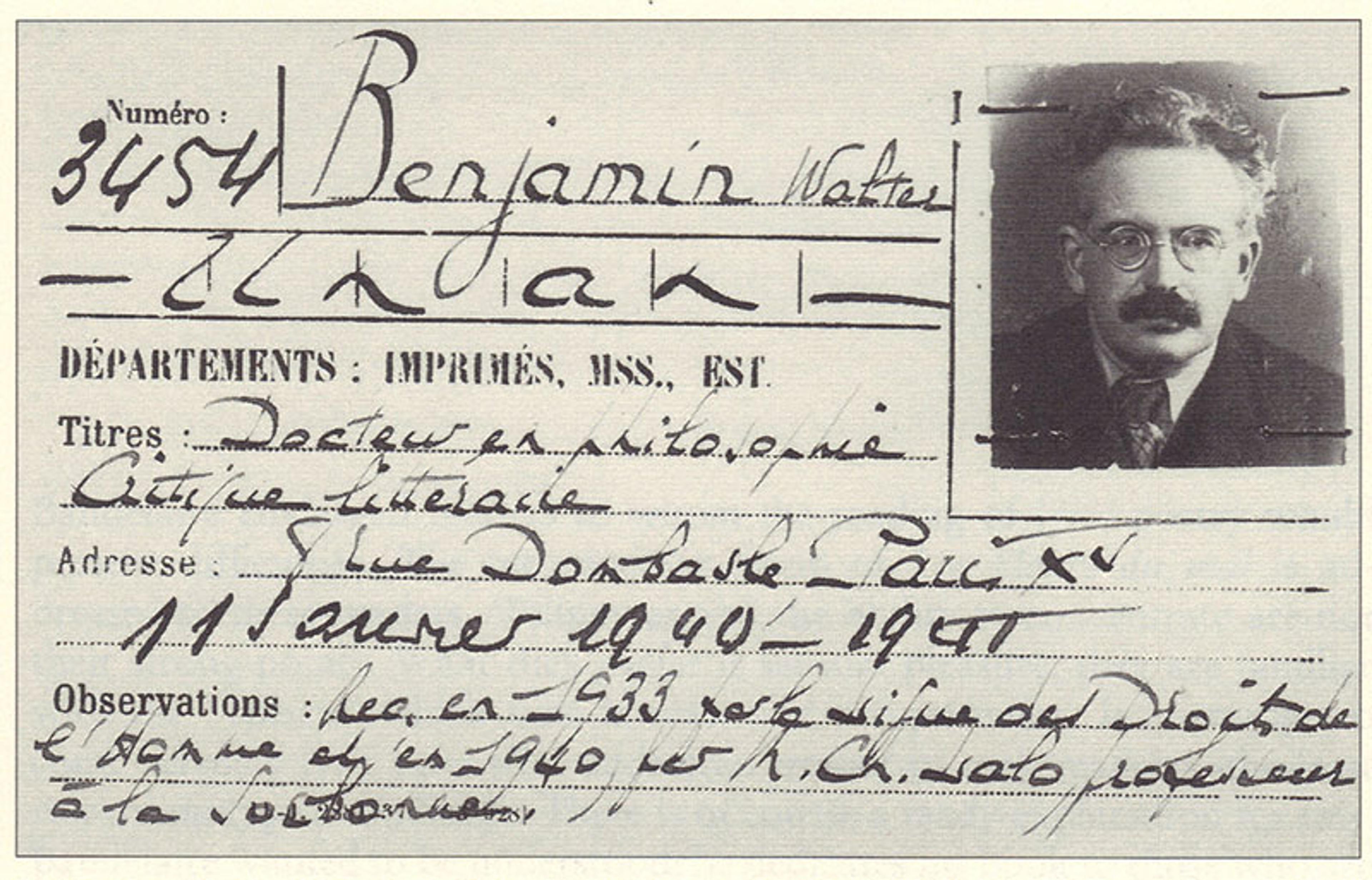

Benjamin’s library card from the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. in 1940. Courtesy Wikipedia.

I think Benjamin is a wholly exceptional figure. It is difficult to find anyone else who was able to combine encyclopaedic erudition and a real gusto for accumulating material and ideas with the sophistication that more frequently goes with being an epigone (one tasked with concluding itineraries rather than opening up new ones) – and with his capacity to innovate, to read the world in a new light, to capture the first signs and elements of the momentous epochal changes that were to come. Those who revolutionise are not typically overly concerned with style – but rather with the need for rupture, destruction and re-invention unhampered by linguistic preoccupations.

Yet Benjamin was a consummately refined revolutionary.

He was the one who first understood, for instance, that the possibility of making multiple copies of a work of art through mechanical reproduction, so that it could be viewed without having to be physically present in the place where it is preserved and displayed, would consequently divest this work of its aura – a combination of distance, singularity and wonder that signalled the superiority of the artist in relation to the world.

What was this sophisticated and creative intellectual, this deep-rooted denizen of capital cities, doing there in that small town on the border between Spain and France? And which book of his was lost? I have followed him to this point, to where the slopes of the Pyrenees descend into Catalonia, to discover what happened to the typescript he was carrying in a heavy black suitcase from which he never wanted to be separated.

Since 1933, Benjamin had been living in Paris with his sister Dora. But in May 1940, after a period with no movement on the front between France and Germany, the German troops invaded neutral Belgium and Holland, proceeding rapidly and encountering little resistance as they did so, largely due to the surprise nature of attack from this direction. They would enter Paris on 14 June 1940. The day before – just the day before – Benjamin had decided to leave the city that he loved but that was rapidly turning into a trap for him.

Before leaving, he gave to Georges Bataille – a writer and intellectual as innovative and enquiring in his way as Benjamin himself – the photocopy of his unfinished work, The Arcades Project. Or perhaps we should say ur-photocopy, since it was the outcome of the first attempts to reproduce documents photographically. The existence of this copy is of significance here because, even if the aforementioned black suitcase had contained the original of this work, the fact that a reproduction of it had been left with Bataille would hardly justify the anxious attachment Benjamin evidently felt towards this item of luggage. When Benjamin left Paris, he had a plan: to reach Marseille, and in possession of the permit allowing him to emigrate to the United States, which his friends Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer had managed to obtain for him, to go from Marseille to Portugal, and embark from there for the US.

Benjamin was not an old man – he was only 48 years old – even if the years weighed more heavily at the time than they do now. But he was tired and unwell (his friends called him ‘Old Benj’); he suffered from asthma, had already had one heart attack, and had always been unsuited to much physical activity, accustomed as he was to spending his time either with his books or in erudite conversation. For him, every move, every physical undertaking represented a kind of trauma, yet his vicissitudes had over the years necessitated some 28 changes of address. And in addition he was bad at coping with the mundane aspects of life, the prosaic necessities of everyday living.

Hannah Arendt repeated with reference to Benjamin remarks made by Jacques Rivière about Proust:

He died of the same inexperience that permitted him to write his works. He died of ignorance of the world, because he did not know how to make a fire or open a window.

before adding to them a remark of her own:

With a precision suggesting a sleepwalker his clumsiness invariably guided him to the very centre of a misfortune.

Now this man seemingly inept in the everyday business of living found himself having to move in the midst of war, in a country on the verge of collapse, in hopeless confusion.

Miraculously, after long forced delays, in stages completed only with extreme difficulty, Benjamin nevertheless managed, at the end of August, to reach Marseille – a city that had become the crossroads for thousands of refugees and desperate people attempting to flee the fate pursuing them. In order to survive, to leave the city, it was necessary to have document after document: in the first place a residence permit for France, then a permit to leave the country, then another to travel through Spain and Portugal, and finally one allowing entrance to the US. Benjamin felt overwhelmed.

In addition, to return to Arendt’s phrase about misfortune, he had always been convinced that it had pursued him – like the ‘little hunchback’ of German folklore, a harbinger of bad luck, a jinx causing his victims to bungle and to fail. He had already experienced many instances of such misfortune: from his failure to get onto the first rung of the academic ladder with his work The Origin of German Tragic Drama (1928), a work nobody had understood, to the fact that, in order to escape the bombing of Paris he so feared, he had moved to the outlying districts of the city and unwittingly ended up in a small village that was one of the first to be destroyed. Benjamin had not realised this apparently insignificant place was at the centre of an important rail network, and therefore liable to be targeted.

In Marseille, he managed to sort out a few things. He gave Arendt the typescript of his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ so she could deliver it to his friends Horkheimer and Adorno (so this work could not have been in the black suitcase either), and collected his visa for the US. But he lacked one crucial document: the exit visa from France, which he was unable to request from the authorities without marking himself out as a refugee from Germany, and thus being immediately referred to the Gestapo.

Only one option remained: to cross over into Spain via the Lister route, named after the commander of the Spanish republican troops who had used it, albeit in the opposite direction, to lead part of his brigade to safety at the end of the Spanish Civil War.

This was suggested to Benjamin by his old friend Hans Fittko, whom he had encountered by chance in Marseille. Fittko’s wife Lisa, then in Port-Vendres near the border with Spain, was helping others who found themselves in the same situation to get across. So Benjamin set out, along with a photographer called Henny Gurland and her 16-year-old son Joseph. They formed a haphazard and totally unprepared group.

They arrived at Port-Vendres on 24 September 1940. And on that same day, guided by Lisa Fittko, they covered the first section of the route in a trial run.

It was more important that the manuscript inside reach America than that he should

But when the time came to turn back, Benjamin decided not to go with the others. He would wait there until the next morning, when they would resume their onward journey together, since he was very tired and would in this way save himself the extra exertion required to go back and return. ‘There’ consisted of a small pine copse. Physically exhausted and disheartened, Benjamin remained there alone, and it is difficult to imagine how he must have spent that night: whether prey to his anxieties or calmed by the nocturnal silence beneath the star-studded Mediterranean sky, so distant from the chill of a German autumn.

The next morning he was joined soon after daybreak by his travelling companions. The path they took climbed ever higher, and at times it was almost impossible to follow amid rocks and gorges. Benjamin began to feel increasingly fatigued, and he adopted a strategy to make the most of his energy: walking for 10 minutes and then resting for one, timing these intervals precisely with his pocket-watch. Ten minutes of walking and one of rest. As the path became progressively steeper, the two women and the boy were obliged to help him, since he could not manage by himself to carry the black suitcase he refused to abandon, insisting that it was more important that the manuscript inside it should reach America than that he should.

A tremendous physical effort was required, and though the group found themselves frequently on the point of giving up, they eventually reached a ridge from which vantage point the sea appeared, illuminated by the sun. Not much further off was the town of Portbou: against all odds they had made it.

Lisa Fittko bade farewell to Benjamin, Gurland and her son, and headed back. The three of them continued towards the village and reached the police station, confident that like everyone else who had gone this way before them they would be given the permits they required to proceed by the Spanish officials. But the regulations had been altered just the day before: anyone arriving ‘illegally’ would be sent back to France. For Benjamin this meant being handed over to the Germans. The only concession they obtained, on account of their exhaustion and the lateness of the hour, was to spend the night in Portbou: they would be allowed to stay in the Hotel Franca. Benjamin was given room number 3. They would be expelled the next day.

For Benjamin that day never came. He killed himself by swallowing the 15 morphine tablets he had carried with him in case his cardiac problems recurred.

During that night, perhaps he thought about the hunchback that had always seemed to have pursued him, arriving now to take him in one last fateful grasp. Had they arrived just one day before, nobody would have raised any objections to their continuing their journey to Portugal – one day later, and they would have been aware that the regulations had changed. They would have been able to seek alternatives, and would certainly not have presented themselves to the Spanish police. There was only one brief interval in which they would meet the worst of all possible outcomes. And this was precisely the one they had chosen. Misfortune had triumphed, and Benjamin had conceded.

For many years, nothing more was known: it seemed as if all trace of his attempted flight had vanished. In the 1970s, at a time when the importance of Benjamin’s work was finally being recognised, many students of his writing set off to Portbou inspired by the memoirs of Lisa Fittko, in which she had revealed to the world her part in getting him there. But they found nothing. No black suitcase, and no gravestone. Benjamin seemed to have disappeared into thin air.

Even today, among the welter of information available on the internet, some of it false, like much else one finds there, there are those who repeat only this version of events. Who maintain that nothing can be known about the suitcase and its contents.

Fortunately, in addition to the internet, I have friends. One of them, Bruno Arpaia, wrote a wonderful novel about Benjamin called The Angel of History (2001). And he is the one who has told me about what actually happened. Because, while it is true that for many years no one managed to find any trace of Benjamin in Portbou, the mystery was later clarified. The Spanish authorities had assumed that Benjamin was his first name (an easy enough mistake to make, since though pronounced differently it is used as one in Spain) and that his surname was Walter. And so they had registered him in the public archives, and then placed all documents relating to him in the court building at Figueres under the letter W.

It was then revealed that he had been buried in the Catholic cemetery, and at some later date moved to a communal grave – and that all of his belongings had been recorded in a ledger, providing an apparently complete and accurate inventory. A leather suitcase (of no specified colour); a gold watch; a passport issued by the US authorities in Marseille; six passport photographs; a pair of glasses; a few magazines or periodicals; some letters; a few papers; a little money. No mention is made of typescripts or manuscripts. But those ‘papers’ – what did that refer to?

What was Benjamin carrying that was so precious to him? Which text, if it wasn’t The Arcades Project, which he had given to Bataille, or the ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, which he had entrusted to Arendt?

Would Benjamin have dragged that suitcase with him if it held only a few personal effects?

To this question, not even Arpaia has an answer. In his novel, with fictional licence, he has Benjamin hand over the typescript to a young Spanish partisan to carry to safety. Someone who during a night in the mountains, prey to extreme cold and desperation, uses it to light a fire with which to save his life.

And fire is a recurrent motif with regard to lost books. As is well-known, paper burns easily. But in reality, in a small town just over the border between France and Spain, in room number 3 in a small provincial hotel, it appears that no fires were lit.

There are those who doubt that the suitcase ever contained a manuscript. But what possible reason would Benjamin have had to lie to his companions in misfortune, and to drag that suitcase with him if it contained only a few personal effects? I’m convinced that there was something of real importance inside. Perhaps notes with which to continue his work on Arcades, perhaps a revised version of his work on Charles Baudelaire. Or perhaps another work altogether, one that is entirely missing, that we do not even know existed.

No, Arpaia does not have the answer, but at the end of our conversation he gives me another story, since Portbou has been the site of many more stories about lost papers.

Less than a year before Benjamin reached Portbou, among the half a million or so people fleeing bombardment from German and Italian planes, and seeking to cross in the opposite direction to Benjamin, there was one Antonio Machado: the great and at the time, unlike Benjamin, genuinely elderly Spanish poet. Machado also had with him a suitcase, containing many poems, that he was forced to abandon there in order to reach exile in France, in Collioure, where he would die just a few days later.

Where are those poems, so compromising at the time because they were written by an enemy of the Franco regime? Where are the pages Benjamin guarded so jealously? Were they really all destroyed? All lost?

Who knows. There might still be some forgotten, yellowing papers in a wardrobe or an old chest in the attic of a house in Portbou: the poems of the old defeated poet and the notes of the prematurely aged European intellectual, conserved together, unknown even to the owner of the wardrobe or chest.

Is it too much to hope that sooner or later – by chance, scholarship or passion – someone will rediscover those pages and enable us to read them at last?

This is an edited extract from ‘In Search of Lost Books’ by Giorgio van Straten, translated from the Italian by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell, published by Pushkin Press.