In recent years, psychology has come under attack as a racist tool of Western thought. No one can deny that it has been used to stigmatise, categorise, infantilise, manipulate and transform our ways of seeing ourselves, each other and even the very function of civilisation. But the study of the mind has simultaneously been a part of the story of anticolonialism and liberation, a potent tool for overcoming delusion and confusion in the face of oppression and assault.

When the Delphic oracle urged the supplicant to ‘Know thyself’, what exactly was to be gained by knowing? Presumably, he was to be liberated from delusion through the capacity to clearly understand his own motives, fears and aspirations. For Socrates, it was the method of dialogue with another person that allowed one to know oneself, while for Epictetus, an acknowledgement of the forces outside one’s control was crucial to knowing. Knowledge of thyself is always embedded in a context. A decolonial psychology becomes possible with awareness that subjectivity is embedded in history and hierarchy.

What happens when the context one lives under is colonial oppression? The modern form of knowing thyself that we call psychology has served as a source of resistance by allowing individuals to forge their own identities within their lived context. In the middle of the 20th century, psychoanalysis served as a language for structuring, theorising and articulating the inner landscape. After the Second World War, when colonial declensions of land and people in Africa and the Middle East bore the strange fruit of new nations, psychodynamic theory offered the potential of analysing the nature of personal and collective trauma through liberatory discourse.

This year, a report from the Holmes Commission on Racial Equality in American Psychoanalysis (APsA) indicates that ‘the “social”’ is deeply embedded in the psyche, and ‘an essential focus for psychoanalytic thought and practice’. The implication is that, in this world of displaced peoples, psychologists must tend to the consequences of history. What’s more, psychology provides a format for self-knowledge through which individuals can articulate their experiences and derive explanations for their sense of dislocation.

In the modern world, we use the language of psychology to manage and assess concepts of agency, mastery and power. Psychology can provide the capacity to critique power, and express suffering and frustration in the face of oppressive economic forces the individual must survive. In recent years, a powerful interest among psychologists in the ‘decolonisation of psychology’ itself aims to isolate and eradicate the epistemic violence caused when Western models of society eclipse and obfuscate local cultural notions of ethics and identity.

The development of an inner landscape through which an individual can know herself constitutes what I like to call the ‘liberatory potential’ of psychology – the potential of psychology to liberate us from oppression. From the proliferation of analysts in Buenos Aires to the work of remarkable individuals in Martinique, India, Egypt and Ghana, psychology has provided a language rich enough to alleviate suffering, buttress the sense of agency and provide tools for discourse. To know oneself in the postcolonial moment of the 20th century and beyond, to achieve true liberatory knowledge, is to conceive an intersubjective space in which one can forensically analyse the consequences of subjugation in our behaviours and thought patterns, and understand them in the context of the wider world.

The great American scholar W E B Du Bois was a student of the psychologist William James at Harvard from 1888-90. This foundation in psychology was subsequently extended during a research fellowship with social scientists in Germany and led to the development of the notion of double consciousness in Du Bois’s book The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

Double consciousness identifies the psychological splitting in perspective that Black Americans often engage in as a response to the misrecognition and alienation of racism. Du Bois remarked that Black Americans have a bifurcated sense of identity in which they simultaneously experience themselves not only as thinking subjects but also as stigmatised, Black bodies. As dramatised by Richard Wright in Native Son (1940) and Ralph Ellison in The Invisible Man (1952), double consciousness is the basis of the imposter syndrome. This self-doubt of intellect and capacities that high-achieving people report derives from the continuous sense of misrecognition they experience through the imposition of double consciousness. The constant siege on one’s dignity creates ruptures in the subjective sense of agency. For seminal thinkers in Africana philosophy, psychological concepts such as double consciousness and imposter syndrome provided a helpful language with which to consider how the emotional lacerations of unequal relations transform cognition and behaviour.

During the mid-20th century, the Martinican psychologist Frantz Fanon (1925-61) drew concepts like double consciousness and stigma from psychology to articulate the neuroses created by the prevalent racist equation of evil and threat with Black skin. He resisted the obfuscations and dehumanisation that came with colonisation and, seeking clarity, paired psychological modes of analysis with the imperatives of humanism and existentialism.

The sense of inferiority for subjugated peoples led to feelings of psychic oppression and alienation

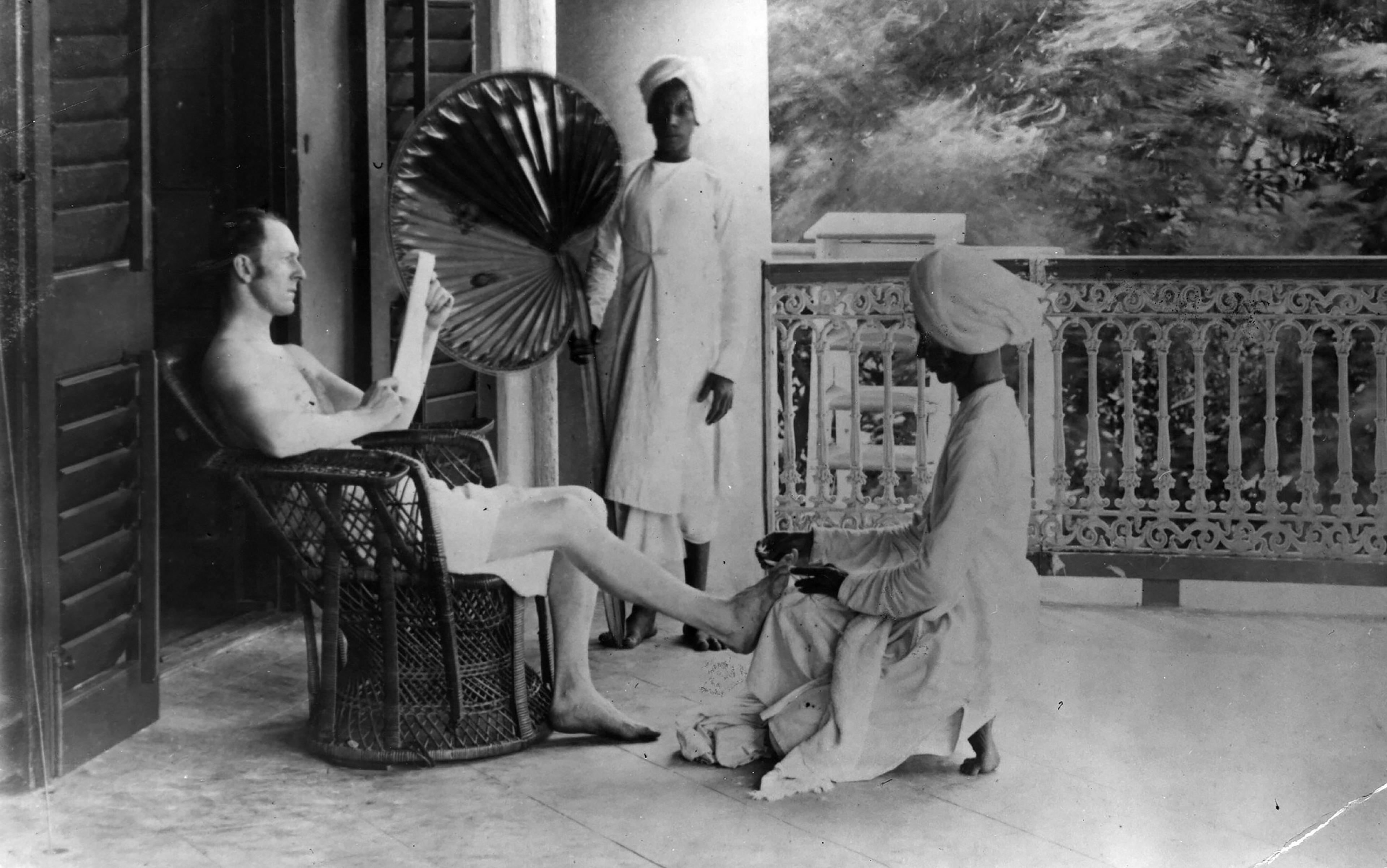

In French-colonised Algeria, Fanon observed the racist practices and beliefs that separated natives from their colonisers through sets of rules, proscriptions and duties. Those lines ultimately had the psychological effect of denying personhood to individuals, causing so much stigma that people came to demonstrate symptoms of alienation and dislocation.

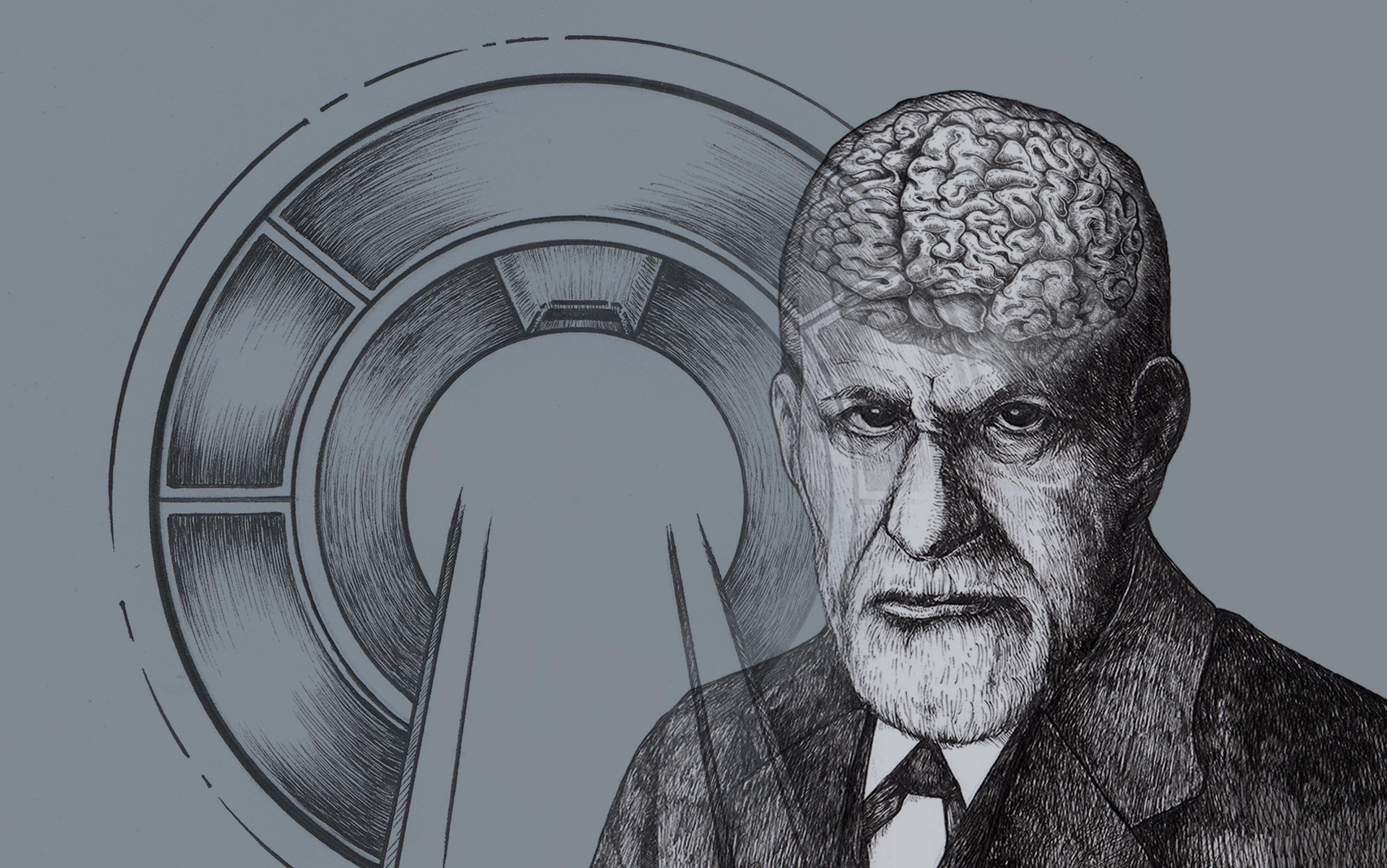

Fanon drew from Sigmund Freud’s notions of repression and mourning and melancholy to understand and analyse the consequences of colonial imposition of racial hierarchy. Similarly, he drew from Alfred Adler’s concept of the inferiority complex to analyse how the sense of inferiority for subjugated peoples led to feelings of psychic oppression and alienation. Fanon aimed to delineate the psychic trauma of racism towards the goal of replacing inferiority with pride. Infusing an archaeology of the toxic socialisation of negroes in the colonies and the metropole into these psychological concepts, intellectuals like Fanon were able to articulate strategies for dissolving oppressive socialisation. Many overlook the fact that Freud himself developed psychoanalysis in the context of his own drive to attain self-knowledge as a minority Moravian Jew in the Catholic Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Psychology can pinpoint the cause, or source, of pathology in the individual, or out in the social environment. This flexibility is one of the reasons it is such an effective form of resistance and liberation. Fanon’s use of psychoanalysis merged with the politicisation of psychology in Algeria during the overthrow of the French colonial administration, starting in 1954. In his position at the psychiatric hospital at Blida-Joinville, he developed techniques to give patients back a sense of agency and remove subtle forms of stigma by modifying the relationship between doctor and patient. He used psychology as a tool for revolutionary critique by tracing the causes of suffering to the structures of colonialism. This approach, which emphasised that pathology arises from the internalisation of relations between people and groups, was effectively an affective politics of resistance. The articulation of pain, alienation and fury were cathartic rejections of oppressive power relations, which were determined by the historical situation – knowledge of thyself is indeed always embedded in a context.

The use of psychology in Fanon’s political analysis and practice was a means to strengthen the sense of agency as knowledge of the inner psychic landscape. Fanon took principles of psychoanalysis like the inferiority complex beyond the psychiatric ward to address how the colonised mind suffers from continuous oppression that estranges the individual from her identity and cultural values. Fanon clarified the intimate psychological causality of this harsh reality to make the connection between the tools of oppression of subjectivity – including dehumanisation through consistent subjugation of will, economic opportunity and territorial segregation – and the Algerian revolutionary struggle for recognition and liberty under French colonial rule. Modern psychiatry affirms that people displaced through exile or civil unrest tend to experience hypervigilance and anxiety as the relational consequences of losing their homes.

Part of the process of colonialism is the importation of narratives that legitimise hierarchies imposed through military and economic force. In India, the Bengali psychoanalyst Girindrasekhar Bose (1887-1953) resisted this epistemic violence by creating a unique amalgam of Advaita Vedanta and psychoanalysis. His leadership of the first and longest-running department of psychology in India at the University of Calcutta and as president of the Indian Psychoanalytical Association underline the significance of his accomplishment. The late Alfred Hiltebeitel, Columbian professor of religion at George Washington University, described how Bose’s interpolations of psychodynamic theory into ancient Vedic texts, like the Upanishads, delivered rich psychological formats to consider ethics and order. Bose’s accomplishment was to maintain local cultural conceptions of the self, the mind and salvation, while incorporating the modern, technical language of psychoanalysis.

In contrast to Freud’s atheism, Bose was a Bihari Vedantist who considered religion a useful palliative. The devotional needs embodied in Vedanta and Mimamsa dogma and practice served as the motivating condition for Bose’s liberatory use of psychology. Ultimately, he discovered profound alignments between the introspective methodology of psychoanalysis and the tenets of Hindu philosophy, including ancient Vedic rituals. As a result, he responded to the imposition of colonial narratives of progress, value and hierarchy, in which Hindu philosophical systems were backward and outdated, by integrating psychodynamic theory into Vedic metaphysics in a way that maintained and strengthened local knowledge practices. In particular, Bose was able to demonstrate that psychoanalysis itself could be framed in the older and more accomplished palliative technologies of Vedanta and yogic practices. Bose deftly navigated differences between Western materialist metaphysics and Hindu notions of nondualism, karma and kāma (desire or wish), and provides us with an example of how psychology inspires synthetic revolutionary possibilities for the postcolonial subject.

Bose and Fanon both resisted the racist narratives of their British and French colonisers by using psychology to develop and maintain more familiar cultural narratives lacking those racist preconceptions of value and legitimacy.

The emergence of modern Egypt provides yet one more example of psychology’s powerful potential to bridge gaps. In mid-century Cairo, popular and academic psychology occupied a position between biological traditions like medicine on the one hand, and prescriptive traditions such as the law on the other. Psychology thus could be applied in institutions within the modernising state. Indeed, the Free Officers who backed Gamal Abdel Nasser attended lectures on psychoanalysis and integrated this information into their organisational plans for the state.

Meanwhile, a circle of intellectuals in Cairo crafted a radical synthesis of Freudian theory and mystical Islam that resisted burgeoning religious fundamentalism on the one hand and blind devotion to Western modernity on the other. Yusuf Mourad’s circle of intellectuals admired the humanist values of the Enlightenment but were also invested in a radical rejection of European colonialism. They developed concepts that perpetuated the collectivist core of Egyptian society by asserting how the self is socialised by family, community and the state. To bridge the gap between the old way and the new, psychology was aligned with the native resources embedded in mystical Islam; used that way, it was a handy tool.

The ethical programme of Islam was fused with modern psychological texts addressing mental health

For instance, psychoanalysis provided a way to analyse psychosexual development in scientific language that was not ethically forbidden. It was similarly used to adapt the 12th-century Persian philosopher Al-Ghazali’s notion of instinct (ghariza) into a Darwinian context. This space of liberal subjectivity was often otherwise censored by religious elites.

In The Arabic Freud (2017), the historian Omnia El Shakry describes how Cairene intellectuals like Mourad used psychology as a systematic liberatory language with which to unite introspection, positivism and phenomenology with Islam. These intellectuals synthesised psychoanalysis and the notion of intuition developed by the French philosopher Henri Bergson with prior traditions of spiritual insight and gnosis in Sufist Islam by emphasising continuities. Proto-psychologists like Ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240) provided Sufi concepts that thinkers like Abu al-Wafa al-Ghunaymi al-Taftazani (1930-94) used to integrate the notion of the unconscious as a reclusive element of the mind with the Sufi concept of batin (the hidden). The ethical programme of Islam, which emphasised the tareeq (way, road) of the Sufi traveller as a battle between the development of understanding and the base instincts of man, was fused with modern psychological texts addressing mental health.

This kind of psychodynamic framing provided people with the discursive tools not only to understand their own motivations, but also to craft frameworks by which to navigate ethical matters. The use of psychology in both India and Egypt demonstrates that psychology is a flexible language that allowed intellectuals to creatively devise a sense of subjectivity that synthesises native and imported knowledge practices so as to adaptively cope in the postcolonial condition.

The anthropologist M J Field pursued a similar line in employing ethnopsychiatry to study local culture in Ghana during the midcentury. Field’s thorough analysis of widespread belief in magic and animistic religion as a form of psychology cast local beliefs on the same plane as ideas being imported from the West. In short, the language of psychology could mediate between alternative systems of belief in a way that did not deny or delegitimise local knowledge practices. If the colonial project is to replace and, eventually, to erase, then psychology can prohibit the dehumanisation of native cultures by rendering commonalities in the human condition. For better or worse, that is why its pronouncements carry moral consequences.

The unique form of West African colonialism that Field analysed included Methodist and Presbyterian cosmologies, tribal identity and local practices. The main traditional religion of Ghana is Akan, which centres around a supreme deity, though there are many variations and subgroups, such as Fanti, Ashanti and Akuapem. These subgroups serve as the basis of communitarian, collectivist identities that persist throughout the country through marriage bonds, economic collectives and social hierarchies across the various power centres of respective groups. Akan religion has been combined with Christianity since the earlier waves of European colonialists starting in the 15th and 16th centuries, though it also remains a distinct set of cultural practices in certain communities.

In her classic text Search for Security (1960), Field describes how traditional psychology based on individualist Judeo-Christian traditions was altered in the context of Akan cosmology. As in many Biblical narratives, rural Ghanaians insist on the prevalence of spirit possessions wherein the possessed individual emits prophesy. Here, magic and medicinal rituals are enacted through the mediation of the suman (a talisman or charm). The ritual she studied is the psychological practice by which individuals act out their guilt. Field writes:

[W]itchcraft meets … the depressive’s need to steep herself in irrational self-reproach and to denounce herself as unspeakably wicked.

Field describes how a belief system that relies upon witchcraft and employs concepts like kra (soul) and sunsum (mind, spirit) to explain psychiatric disturbances constituted a form of psychology whose function was to shape an individual’s inner landscape as well as to provide a language with which one may testify to their community.

Psychology provides an intersubjective mirror for social interaction across cultures and value systems

Witchcraft seeks goals similar to those of psychology: to alleviate suffering and manage the trauma and stigma an individual experiences in their local context. Yet, the presumed universalism of colonial enterprises often serves to obfuscate the historical and experiential fact that local traditions create drastically distinct inhabited worlds. Akan practice can be portrayed as witchcraft for the purposes of psychological purging, but it has other uses for identity, emotional coping and metaphysical practices that involve mystical states of mind in distinct cosmological systems. It is the historical crafting of identity in the context of metaphysical concepts such as the complicated strands of Akan, Christian and animist practices that make up an individual’s way of life. That is to say, psychology as a way to know oneself cannot be extricated from the complex living cultures of the day.

This brings up the motivation behind decolonial psychology: that the human sciences are necessarily a colonial imposition because they were created by Western intellectual society. This is a powerful interpretation, yet psychology is flexible and can be adapted to the opposite end. Psychology might be used to colonise the way we think of our minds and bodies, but it can equally be employed as a language to decolonise from these impositions.

By addressing the colonial nature of the human sciences, the psychologists Paul Parin, Goldy Parin-Matthèy and Fritz Morgenthaler combined ethnographic methods and psychoanalysis to explore transcultural relations between self and society. Their extensive interviews and consultations in Mali in the 1950s led to ethnopsychoanalysis, a new way of assessing how social practices, especially concerning sexual mores and the anxieties they produce, shape ego identity. For example, they theorised how so-called sexual perversions of adolescent polygamy served as creative solutions to psychological difficulties arising in early development. Morgenthaler was led by this work to consider how the deeply intersubjective nature of the mind required mutual knowing, or complementarity, to engender emotional healing. This suggests a model for healing through a sophisticated, shared language with which to understand, analyse and communicate our shared culture and inner lives.

Psychology provides an intersubjective mirror for social interaction across cultures and value systems. Such intersubjectivities allow for the development of morality, ethics and understanding. In their application, these mirrors create space for consideration of the irreducibility of the human experience.

As a set of therapeutic practices, psychology can restructure subjectivity in a political context because its practices align individuals through shared values. We observed this in the work of Frantz Fanon, Girindrasekhar Bose, M J Field and Yusuf Mourad. For them, psychology shapes the potential of agency for the political subject; this is the wellspring of the current movement to decolonise psychology.

During the tumult of the 20th century, individuals were scattered across the globe. Employing shared symbols and methods, psychology was used to minister to the travails of dislocated peoples. In this regard, it helped satisfy the human drive for sense and purpose by providing techniques to promote agency and mastery. Indeed, the unique human capacity for reflection means that knowledge is a form of power. What psychology provides is the language for exercising that power and then liberating the oppressed by uncovering for individuals the context within which they exist.