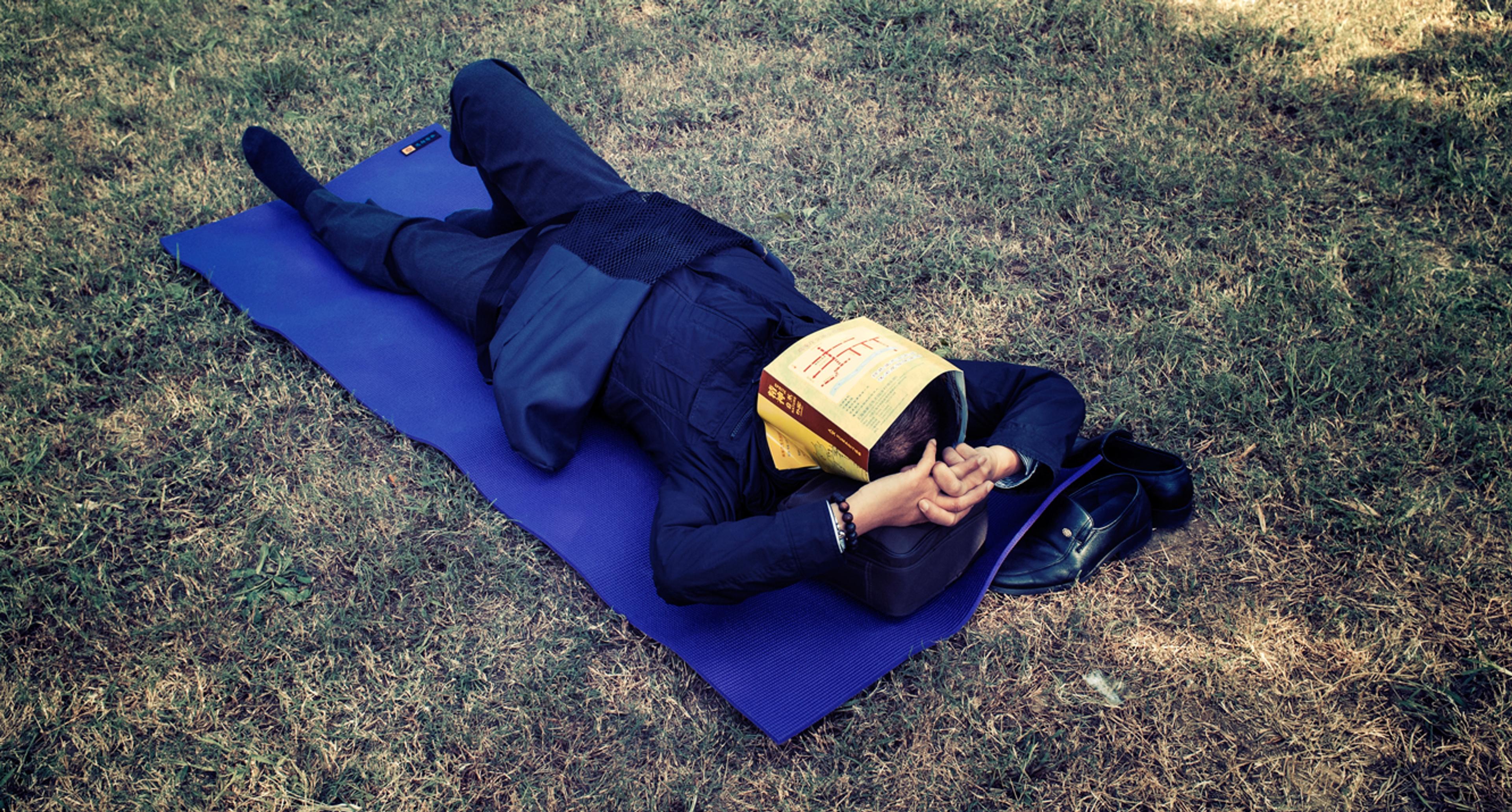

Whenever I travel abroad, I like to arrive with a few phrases in the local tongue. Fluency is another matter. The son of a language teacher, I learned French as a boy. I picked up Spanish during a ramble through Mexico in my 20s. Since then, I’ve been busy. Despite a lifelong yearning for Italian, I reached middle age without getting much beyond per favore and grazie. Recently, an invitation to a conference near Milan made me eager to venture further. But my days were crammed with work deadlines and family obligations; there was no room for an evening course or a regimen of home-instruction through an online app. Maybe, I conjectured, I could master la bella lingua by listening to recordings in my sleep.

Almost a century ago, a fad for sleep-learning swept the industrialised world, ending only after neuroscientists determined it was physiologically impossible. Yet today, a growing body of research suggests they were wrong. Sleep-learning appears to be heading for a revival, on a far more solid scientific basis than its earlier incarnation. By subjecting sleep to a few engineering fixes, we could minimise the time our brains are offline each night, gaining precious hours for absorbing information. Over many nights, we could vastly expand our stock of knowledge and skills, or even treat stubborn addictions and psychological traumas. All of which raises an unsettling question: should the prospect be welcomed or dreaded? If we harness sleep for self-improvement, will we lose something essential about ourselves?

The idea that humans can learn during slumber dates back at least to biblical times, when God gave Jacob a glimpse of his destiny in a dream of angels climbing a ladder to heaven. But the first person to make money from the concept was Alois Benjamin Saliger, a Czech-born New York-based businessman and inventor – ‘tall, spare, thin-lipped’, according to a contemporary account, ‘with piercing eyes and a wide forehead’ – who in 1932 patented the Psycho-Phone. A phonograph fitted with a repeating mechanism and a tiny acoustic horn, the device was meant to sit by a sleeper’s bed and replay spoken-word recordings at the volume of a whisper. It was marketed with disks whose titles included Prosperity, Inspiration, Normal Weight, and Mating. ‘I desire an ideal mate,’ Saliger intoned on the latter record. ‘I radiate love. I have a fascinating and attractive personality. I have a strong sex appeal.’ If the machine functioned as advertised, the user would awaken filled with irresistible confidence, ready to stride off and conquer his chosen territory.

The Psycho-Phone operated on the premise that people are as suggestible while asleep as they are under hypnosis, an unproven theory picked up by Aldous Huxley in his dystopian novel, Brave New World (1932). There, recorded messages are used to train sleeping children in the values of a soulless future society. A proud official in the book calls the new method, dubbed ‘hypnopaedia’ by Huxley, the ‘greatest moralising and socialising force of all time’.

Although hypnopaedia was never employed for mass indoctrination in the real world, it came to be widely used as a tool for teaching new skills or changing unwanted behaviour. Scientific studies seemed to show it worked. In one study, a group of sleeping men heard a recorded list of Chinese words and their English translations; the next day, they scored significantly better on a comprehension test than a control group. In another study, 20 boys with a nail-biting habit were played the phrase ‘my fingernails taste terribly bitter’ 300 times a night for 54 nights; by the end of the trial, 40 per cent had reportedly overcome their vice. The technique grew particularly popular in the Soviet Union, where whole villages were said to learn foreign languages while dozing.

The backlash came in the 1950s, when scientists began using electroencephalography (EEG), in which electrodes are used to measure the brain’s electrical activity. With this technique, they could finally determine whether subjects were, in fact, asleep rather than drifting near sleep or just resting. When the Rand Corporation researchers William Emmons and Charles Simon repeatedly played a list of 10 words to men whose EEGs showed an absence of alpha waves (a reliable gauge of sleep), their performance on a memory test upon awakening was no better than chance. Other EEG-monitored trials drew similar results. Scientific consensus soon concluded that the sleeping brain was incapable of absorbing outside information, and hypnopaedia was consigned to the realm of quackery.

Now the pendulum is swinging again. Although no practical method yet exists (despite the claims of online hucksters), recent studies suggest that hypnopaedia might be possible in principle. And, if certain technical challenges can be overcome, it could truly usher in a brave new world.

The new interest in sleep-learning comes from a deeper understanding of what our brains do as we lie inert and drooling. Experiments have long shown that people who get a good night’s sleep are better able to recall what they learned the day before than those who don’t. But why?

One theory held that the brain rehearsed the day’s new information during dreams, characterized by rapid eye movement (REM). Lab research eventually dispensed with that idea, however. By the mid-1990s, the data was pointing another way: memories are rehearsed mainly during the deep, dreamless stage known as slow-wave sleep (SWS), so-called because the brain cycles leisurely between peaks and valleys of electrical activity. Researchers found that during SWS, specialised ‘place cells’ in a rat’s hippocampus replay the route of a maze that the animal learned to run during the day. Later studies indicated that humans rehearse new memories in much the same way. The hippocampus functions as a temporary storehouse for memories until slower-growing but more permanent connections for those same memories form in the cerebral cortex, where language, sensory perception and thought reside.

As it became clear how much activity the sleeping brain devoted to digesting the day’s learning, the notion of learning while asleep came to seem less far-fetched.

In 1996, Japanese researchers put a rudimentary form of sleep-learning to the test by eliciting what psychologists call a conditioned response – linking two stimuli so that repeating the second one triggers a response ordinarily associated with the first. They delivered mild electric shocks to the legs of five sleepers while playing a tone; after awakening, the subjects experienced increased heart rates when they heard the tone alone. The study proved that the sleeping subjects recalled the tone, at least subconsciously.

A much more ambitious conditioning trial came in 2007, when a team, led by the medical psychologist Jan Born at the University of Lübeck, Germany, used olfactory cues to trigger fully conscious, or declarative, memories. They began by piping the odour of roses into subjects’ nostrils while they memorised the position of objects on a computer screen. Then, some of the subjects were exposed to the fragrance again during SWS. When they awoke, they recalled the locations of the objects 15 per cent more accurately than a control group not exposed to the smell during sleep.

In subsequent experiments, the neuroscientist Ken Paller at Northwestern University in Chicago taught subjects to play a short melody on a keyboard; later, as the subjects napped, the tune was played repeatedly to half of them. After waking up, that group played it with fewer mistakes than the cohort who had slept in silence. Another study was directly relevant to my linguistic quest: at the Swiss National Science Foundation, subjects who were taught Dutch words during the day proved better able to recall and translate them after those words were replayed during SWS at night. These music and language trials show that auditory cues trigger memory rehearsal for certain tasks directly – no need for conditioned association at all.

Anyone seeking to master a musical instrument or explore the intricacies of particle physics could do so with almost magical ease

Together, these studies offered something close to a proof of concept. But one element was missing: all the experiments involved skills or information that had first been learned during waking. To demonstrate hypnopaedia in action, scientists would have to teach a sleeping subject something new.

In March 2015, researchers reported in the journal Nature Neuroscience that they had done just that. The team, led by the neurobiologist Karim Benchenane of the National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris, began by implanting electrodes in the brains of mice, and recording the firing of place cells as the animals navigated a metre-wide circular platform. The researchers chose one cell for each mouse, then waited until it reactivated during sleep. At that moment, they zapped the brain’s reward centre with a low-voltage electric current, creating a sensation of intense pleasure. When the mice awoke, they rushed to the location associated with the place cell, lingering there in apparent expectation of another reward. The scientists had created a false memory, changing the animals’ behaviour in ways that did not result from prior waking experience.

Benchenane’s study used positive reinforcement to train its subjects. Meanwhile, neuroscientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel took the opposite approach with human nicotine addicts, exposing them during SWS to the odours of cigarettes and rotten eggs or fish. Thanks to that aversive conditioning, participants smoked 30 per cent less the following week.

And at Northwestern University, the neurology post-doc Katherina Hauner devised a way to erase negative associations during SWS. First, she showed volunteers images of faces while delivering an unpleasant electrical shock; at the same time, she exposed them to odours of mint, lemon or pine. The subjects soon learned to associate the faces with pain. Then, while they slept, Hauner exposed them to the odours alone. Initially, they responded with fear (as measured by tiny amounts of sweat on the skin), but the reaction diminished with repetition. When the subjects awakened, their anxiety at seeing the faces was reduced as well.

It’s easy to see how transformative such techniques could be. ‘We’re at the cutting edge of trying to figure out what the sleeping brain is capable of doing,’ Paller said when I called him in Chicago. In the near term, ‘we might improve learning by taking advantage of the processing that already happens during sleep’. An updated Psycho-Phone, designed to deliver cues during SWS, might help a student master a subject faster, though daytime study would still be necessary. The device might be paired with a headband delivering transcranial electric stimulation, which has been shown to deepen SWS at certain frequencies. A deluxe package could include an aroma-generating machine to boost the overall effect.

Sleep-learning could be used in therapy to replace traumatic memories with less charged recollections of the same events. That might require drugs to pry open the neural gates, allowing a Super-Psycho-Phone to funnel content directly into the hippocampus. Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley recently devised a method for recording a subject’s neural patterns as she watches a video, translating them into computer code, and generating a fuzzy approximation of the original imagery. Some day, perhaps, the process will be refined and reverse-engineered, producing neuro-downloadable multimedia courses in Italian for beginners.

The potential is obvious, and not only for over-scheduled language geeks such as me. Students in every field might achieve proficiency twice as fast as they do now, and go on to learn twice as much. Anyone seeking to acquire new job skills, master a musical instrument or explore the intricacies of particle physics could do so with almost magical ease.

But the risks seem palpable, too. Hypnopaedia could undermine the restorative functions that normally occur during sleep – for example, the pruning of excess neural connections to make room for memories to come. After a night of unconscious exam-cramming, it might be harder to learn anything new the next day. Learning while sleeping could also make less brain energy available for consolidating long-term memories, perhaps leading to the erasure of last year’s trip to Istanbul. It might disrupt the nocturnal cleansing of the brain’s metabolic wastes by glial cells, increasing the learner’s vulnerability to neurodegenerative ailments such as Alzheimer’s disease.

During sleep, the brain rebalances both the immune and endocrine systems; that’s why sleep disorders are associated with ills including depression, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Tinkering with the controls might have nasty consequences.

Less tangible costs must also be factored in. I am old enough to remember life before smartphones, when being disconnected at certain times of day, or even for days at a time, was perfectly acceptable. That state of tranquil unreachability is a lost Eden. Now, if my editor emails an urgent query, I have no excuse not to respond during waking hours. Sleeping hours, at least, remain off-limits. But in the hypnopaedic future, that boundary, too, could fall away.

Imagine your boss asking you to download data for tomorrow morning’s presentation into your brain after lights-out. Imagine your coworkers discussing the TV shows they binge-watched in the arms of Morpheus. Picture your Facebook friends posting updates on their nightly absorption of Mandarin. What will we sacrifice by succumbing to the demands of 24-hour accessibility, availability, productivity?

In his book Healing Night (2006), the sleep psychologist Rubin Naiman tells of a game he played with his mother as a child. She would ask: ‘What is the best thing in the world?’ Little Rubin would shout out guesses (Toys! Cartoons! Ice‑cream!) until she revealed the correct answer: ‘Night.’ Naiman’s mother had spent four years in a Nazi concentration camp; during that hellish sojourn, she had learned to cherish the hours of darkness as a promised land. ‘Night brought sleep,’ he writes, ‘a vital daily measure of peace. Sleep, in turn, served as a natural bridge to dreams. And dreaming opened a mysterious portal to a more malleable and compassionate reality.’

‘We talk about falling in love and falling asleep. Both require a kind of surrender’

Such reverence is common in traditional societies, Naiman observes, but has been largely discarded in the over-illuminated West. Most of us see night as an inconvenience and sleep as nothing more than a means of recharging for the following day. We get by on as little sleep as possible, and take pills to knock ourselves out when it doesn’t arrive on schedule. Then we fuel ourselves with stimulants to compensate for the deficit in genuine rest. Naiman argues that our ‘wake-centric’ worldview is undermining our spiritual as well as our physical and psychological health. We could benefit, he suggests, by ‘restoring a sense of sacredness to our nights and night consciousness’.

When I asked Naiman his opinion of hypnopaedia, he likened it to using lovemaking to burn calories, or eating while using the toilet. Sleep is a time for digesting data, not ingesting it, he told me. It’s also a time for abandoning our diurnal strivings, for wandering among the inner mysteries. ‘We talk about falling in love and falling asleep,’ Naiman said. ‘Both require a kind of surrender.’ One of the chief pleasures of sleep – as of love – is that it pulls us out of time, into a realm where every moment is its own reward.

Hypnopaedia, by contrast, is about refusing to fall. It represents wake-centrism’s ultimate aim: to conquer night entirely, reducing it to a fully exploitable colony. In such a territory, going to bed without your headphones might become as unthinkable as leaving the house without your phone. Somewhere, surely, a latter-day Saliger is plotting to profit from such a scenario.

I hereby post my ‘Do not disturb’ sign. Please, Alois: just let me sleep.