I wake up, faintly groggy with sleep, and try to guess the time. Midnight is surprisingly noisy, with a steady stream of traffic bringing people home from the West End in London, while 3am carries a curiously muffled sound, and 4:10am is when the first aeroplane skims my house with its familiar whine of descent. As my ears strain into the darkness, I sense the soft silence of 3am. Once I would have groaned, cursed and plugged the (largely ineffectual) sound of gently lapping waves into my ears. But, tonight, I listen to the emptiness for a few pleasurable moments, then I reach for my notebook and a candle.

I’ve had insomnia for 25 years. Three years ago, after a series of bereavements, I stopped battling my sleeplessness. Instead, I decided to investigate my night brain, to explore the curious effects of darkness on my mind. I’d long felt slightly altered at night, but now I wondered whether darkness and sleeplessness might have gifts to give: instead of berating myself, perhaps I could make use of my subtly changed brain.

I’m not the first person to notice a shift in thoughts and emotions after dark. ‘Why does one feel so different at night?’ asks Katherine Mansfield in her short story ‘At the Bay’ (1921). Mansfield herself became more and more fearful after dark, often barricading herself into her apartment by pushing all the furniture against the front door. And yet, later in life, insomniac nights became one of her most creative times, as she confided to her journal:

It often happens to me now that when I lie down to sleep at night, instead of getting drowsy, I feel more wakeful and I … begin to live over either scenes from real life or imaginary scenes … they are marvellously vivid.

Mansfield referred to her nocturnal imagination as the ‘consolation prize’ for her insomnia.

Around the same time, Virginia Woolf was pondering her own feelings of ‘irresponsibility’ that struck when the lights went down. She too recognised that night rendered us ‘no longer quite ourselves’. After completing each of her books, Woolf was plagued by insomnia – which she made use of to plot out her next novel. ‘I make it up in bed at night,’ she explained of her most inventive novel, Orlando (1928). Night was also a time of epiphany: after protracted struggles with her novel The Years (1937), Woolf’s dramatic breakthrough came ‘owing to the sudden rush of two wakeful nights’ when she was finally able to ‘see the end’. A few years later, the writer Dorothy Richardson noted that, around midnight, ‘she grew steady and cool … it was herself, the nearest most intimate self she had known.’ In her fictionalised autobiography, Pilgrimage (1915-38), Richardson’s alter-ego Miriam finds her most authentic, radical and original self in the solitude of her wakeful nights. For Richardson, reading and writing when she should have been sleeping were acts of resistance, acts that revealed herself to herself, undistracted by the detritus of daylight.

My night-awakenings began during my first pregnancy. Ten years later – with four children and several years of working across time zones under my belt – a full night of sleep in a single stretch had become a rarity. Most nights, I woke between 2am and 4am, tossed and turned for an hour, then read until I drifted back for a (short) sleep before the alarm went off. I invested in sleep aids: melatonin, weighted blankets, eye masks, sleep-inducing supplements, oils, mattresses, pillows, sheets, pills, apps, bed socks. I experimented with various sleep hygiene routines proposed by ‘experts’. To no avail.

The latest statistics suggest that one in six of us cannot get to sleep, or stay asleep, a figure that is higher for women. At the last count, 8 per cent were taking sleep medication and 11 per cent were regularly splashing out on sleep aids. In 2019, the global market for sleep products was valued at $74.3 billion. Experts predict it will be worth $125 billion by 2031. Frightening, and sometimes misleading, stories appear regularly in the media linking poor sleep to obesity, heart disease, dementia and premature death.

A historical perspective offers us some help here. Sleep deprivation is nothing new: women have always been responsible for night-nursing multiple (often sick or dying) children, elderly relatives and animals; wash days often started at 3am; mattresses were thick with lice; winter nights were ice-cold. Like us, our ancestors suffered from many of the same physiological disruptions now linked to poor sleep, from menstrual and pregnancy cramping to the fluctuating progesterone and oestrogen of the menopause. Like us, they routinely experienced the stresses and anxieties now known to disrupt sleep.

I put away my sleep aids and let my grieving brain lean into the dark nights

Published and unpublished letters and journals show that, for centuries, many women embraced nocturne, finding within it a time of solitude and creativity. The literary critic Greg Johnson in 1990 noted that female writers seemed to have a peculiar talent for making ‘creative profit’ from their insomniac nights. He is right, and not just about writers. Over eight months of wakeful nights, the artist Louise Bourgeois produced her Insomnia Drawings (1994-95), a series of 220 sketches. The Insomnia Drawings were immediately snapped up by the Daros Collection in Switzerland, making instant ‘creative profit’ for Bourgeois, who also credited their production with easing 50 frustrating years of nocturnal tossing and turning. Lee Krasner’s ‘night journey’ paintings, made between 1959 and 1962 in the wake of two bereavements, are now among her most valuable and coveted. Meanwhile, Sylvia Plath wrote Ariel (1965), her most brilliant and acclaimed poetry collection, ‘in the blue dawns, all to myself, secret and quiet.’ Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Margaret Thatcher used the sleeping hours to increase the volume of their (arguably bold) output. Enheduanna watched the stars and produced the poetry that made her literature’s earliest known author. And Vera Rubin discovered dark matter, later saying of these wide-awake and alone nights at the telescope: ‘There was just nothing as interesting in my life as watching the stars every night.’

I call these women my Night Spinners.

Several years ago, when I lost loved ones, my flimsy sleep disintegrated and I lost all appetite for battle. Inspired by aeons of Night Spinners, I put away my sleep aids and let my grieving brain lean into the dark nights. When I woke (which could be any time between midnight and 4am), I got up and wrote, drew, watched the stars. I slept outside (night after night), went for long walks, swam in lunar-light, and taught myself the constellations and the phases of the Moon. I tracked and surveyed glow worms and moths. I watched badgers, and followed the call of owls and nightingales. I discovered a mesmerising nocturnal world.

My nocturnal mind was different. Why did I feel both more fearful and more tranquil? Why was I more inclined to fret and fume? To behave with greater recklessness? Why did images, ideas, memories so often collide in a curious collage of colour and novelty? Writing problems I encountered during the day found solutions as I ambled round the darkened house, peering at the night sky from every passing window. In the middle of sleepless nights, my mind felt less logical, less methodical. My grip on assessing and prioritising less assured. But in return, my inner critic fell silent. Ideas and thoughts meandered, melded and merged. I refused to pass judgment, but in the morning, when I looked afresh at whatever I’d written in the night, I often liked it.

From the work of chronobiologists, we know that our bodies – our blood, breath, bones, saliva and skeletal muscle – change at night. Breast cancer cells divide more quickly. Muscles weaken. Our fat cells, kidneys and intestines become slow and sluggish. Blood pressure drops. Appetites fade. Our temperature falls. Many of these changes appear to be tied not to sleep but to darkness. Scientists are beginning to understand that our brains are also altered at night, most notably as they cycle through a series of sleep stages. As I researched the Night Spinners, a pioneering study called ‘The Mind After Midnight’ (2022) appeared in my email inbox.

According to its authors (a group of eminent sleep scientists in the US), as hormones rise and fall, so the brain shape-shifts. The researchers had noted a greater risk of suicide, self-harm and other ‘risky’ behaviours among depressed people awake at night. They weren’t sure why this happened but suggested a few possible explanations. Was it an evolutionary adaptation designed to keep us vigilant and ready for action at a time when we were once most at risk of predation? Was it a result of synaptic saturation, whereby the brain rests in readiness for another day and so can’t function with its usual deftness and clarity? Was it because of altered hormones – rising melatonin, falling cortisol, dawn-peaking dopamine? Or was it because of the quietening of a vital neural network responsible for executive function, for managing our thoughts, actions and emotions – and known collectively as the prefrontal cortex? The prefrontal cortex (sometimes called our command and control centre, and thought to be the most highly evolved brain region) is very sensitive to sleep and sleep deprivation. Researchers speculate that it takes a restorative break at night – leaving us fractionally less rational, less organised and a little more at the whim of our emotions.

A resting prefrontal cortex might also explain why studies indicate that we are more likely to feel enraged and fearful at night. Or why reformed gamblers, drinkers and smokers are more likely to succumb to old temptations. Or why the celebrated writer Jean Rhys – who frequently wrote at, and about, night – was described by her biographer as ‘a lap-dog’ by day and ‘a wolf’ by night. Rhys liked to rise at a ‘wolfish’ 3am and ‘smoke one cigarette after another’, describing this dark hour as ‘the best part of the day’, when her thoughts were subtly altered. At night, it seems, the filter between us and the outside world is fractionally thinner and frailer. It’s not that our emotions change, but that our ability to control changes. We experience the world more viscerally: the highs are higher and the lows are lower.

The pioneering 15th-century feminist Laura Cereta had subversive ideas as she wrote through the night

This nocturnal rawness and instability could be due to insufficient sleep: when Japanese researchers used MRI to investigate, they found that blood flow between the amygdala (sometimes called the brain’s emotional HQ and our threat-detection hub) and the prefrontal cortex slows down when we don’t get enough sleep. In other words, our night brain could be partly explained by insufficient delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the prefrontal cortex. The researcher Andrew Tubbs – co-author of ‘The Mind After Midnight’ study – thinks that sleep deprivation might act as fuel for the night imagination. Tubbs told me that sleeplessness ‘can increase connectivity between disparate brain regions … as some brain regions become exhausted, [neural] connectivity increases so that other brain parts can compensate.’ He speculates that, as the brain is nudged into processing information ‘in unusual ways, it throws up novel and unusual ideas.’

Studies also suggest that, in women, the prefrontal cortex is larger and more active than in men. Might some women find it easier to free themselves, after dark, from the constraints of their diurnally active brains? Could this explain why Joan Mitchell’s paintings changed dramatically when she began night painting? Or why the pioneering 15th-century feminist Laura Cereta had such subversive ideas as she wrote through the night? Both women certainly thought so – Mitchell continued to paint at night for the rest of her life, while Cereta maintained that her ‘sweet night vigils’ were responsible for the ‘red-hot anger [that] lays bare a heart and mind long muzzled by silence.’

Nightly hormonal change may also affect our insomniac minds, colouring our emotions and perceptions. For instance, scientists now think that dopamine may be both a hormone of creativity and connected to light/dark cycles. When the anthropologist Polly Wiessner studied the Kalahari Bush people, she noticed that the way in which people communicated shifted after dark, becoming more imaginative, evocative and symbolic when gathered around a fire at night. We don’t know whether the speculated evening peaking of dopamine receptors contributed, but Wiessner noticed the way in which this linguistic shift contributed to greater empathy and more tolerance. I too noticed how, awake at night, I often felt more receptive, compassionate and open-minded. Things I might have brushed aside or considered unduly esoteric by day took on a new poignancy and possibility.

As I embraced sleeplessness, I became aware of the calming effects of scanning the night sky. In 2001, the psychologist William Kelly noticed that many of his students found great pleasure in star-gazing. It seemed to yield a subtly altered state of mind, and Kelly decided to investigate. Over the next decade, he ran a series of experiments, finding that people who enjoyed looking upwards into starry darkness also exhibited greater curiosity, were more open to new experiences, and more inclined to think fantastical thoughts. They were also more likely to wholeheartedly engage with whatever grabbed their interest, to mull over unusual ideas and fantastical possibilities, to seek out novel sensations. Kelly coined the term ‘noctcaelador’, a mash-up of the Latin nocturnus meaning ‘night-time’, caelum meaning ‘sky’, and adorare meaning ‘to adore’.

In 2016, together with his colleague Don Daughtry, Kelly carried out another study. He had an inkling that night sky-watching might also be connected to more lateral thought: his survey of 233 students suggested he was right. Did looking star-wards loosen the imagination, he wondered, or were creative people just more likely to gaze upwards at night? Kelly also wondered whether there might be a third variable influencing the relationship between star-gazing and creativity. Today, awe scientists think that looking at the night sky induces a sense of profound wonder, capable of lowering blood pressure, reducing inflammation, and increasing levels of oxytocin. These scientists might say that Kelly’s ‘third variable’ was a feeling of awe sparked by observing the constellations. But I think Kelly was on to something that goes beyond awe, that he had stumbled on the Night Self – the version of ourselves wired for nocturne.

I needed to retrain my fearful night brain via a steady process of habituation

I discovered another behavioural trait of my Night Self: the psychological effects of an absence of light. We know that women are more affected by darkness. Many of my friends cannot sleep alone in an empty house, let alone take a solitary walk, at night. Studies show that one in two women feels unsafe walking alone after dark, even in a busy public place. Being in darkness frightens many of us. With a less active prefrontal cortex to talk down our fears, wide-eyed nights can balloon into occasions of terror in which we douse ourselves in artificial light, to feel safer.

Fear impedes the workings of our more imaginative and reflective night brain, but several studies have already linked the rise in breast and prostate cancer with excessive night light. Other conditions are being linked to bright nocturnal illumination – depression, anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder. Some researchers point the finger at the blue-rich LED lights that have now largely replaced all the earlier incandescent (and less blue-rich) bulbs. I decided that if I was to benefit creatively from my sleepless nights with my health intact, I needed to retrain my fearful night brain via a steady process of habituation. On ever lengthier night walks, I paid close attention to my shifting senses and to my nocturnal amplified sense of sound and smell. Studies suggest that even our olfactory bulb is governed by circadian rhythms, growing more acute after dark.

I grew to love my wakeful nights. All that remained was to rid myself of the fear of an early death – as threatened by endless headlines. The Night Spinners reminded me that premature death wasn’t inevitable: lifelong insomniac Louise Bourgeois lived dementia-free until the age of 98; Proust’s night-working housekeeper, Céleste Albaret, lived until 92; and sleepless star-gazer Caroline Herschel was a healthy 97 when she died in 1848. It helped too that new research trickled out questioning the age-old assumptions. As one longitudinal study stated: ‘In women, mortality was not associated with insomnia and short sleep duration.’ I was not about to die from my broken nights – I was free to enjoy them! Men, however, may need to be a little more circumspect. More research is needed, but early studies indicate that women might be more metabolically resilient to short or broken nights.

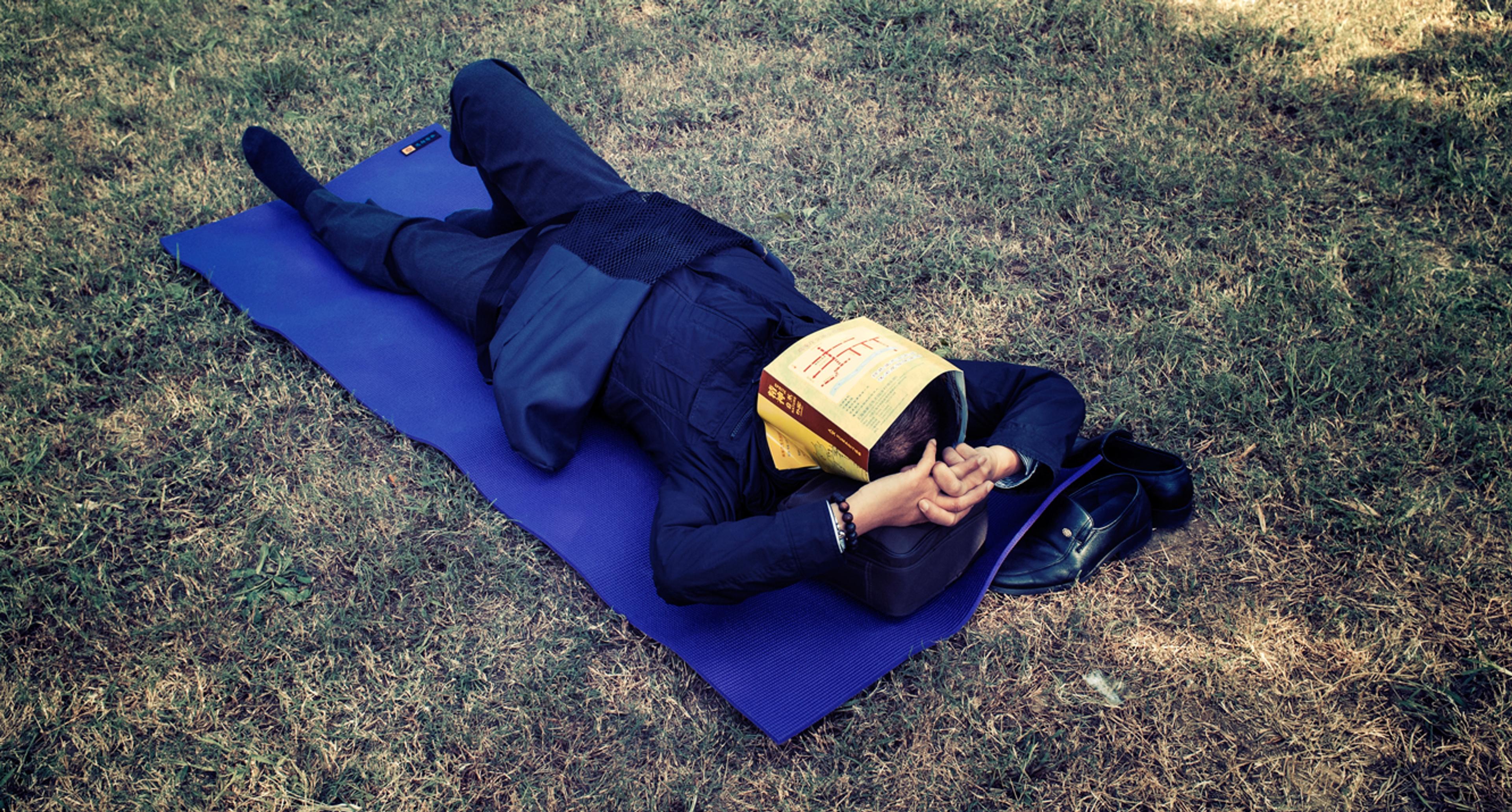

To be clear, like any sleep-deprived person, I longed for a luxurious night of uninterrupted slumber. But, as I became acquainted with the gifts of darkness, so my sleep slowly returned. Leaning into my Night Self, being in a darkness that few of us experience in our light-saturated world, provided an antidote to today’s stress-inducing sleep zealotry as well as to my own fear of the dark. I still have runs of splintered sleep, but I no longer let them disturb me. I’ve learnt that a 20-minute power walk reboots my weary brain as well as a nap, that yoga nidra is almost as restful as sleep, and that reflecting when I should be sleeping might be good for my brain. Best of all, I have a fat notebook of night-ish lyrics and poems, the sorts of writings my sensible Day Self would never countenance. One day I might use them for my own ‘creative profit’.