Westerners who see ancestor worship as something only other cultures do should look around: signs of its devout practice are everywhere. We have park benches in memory of those who once sat there, plaques to the famous inhabitants of buildings, statues of the great and good in every square.

Our greatest acts of devotion are pilgrimages to where venerated predecessors lived, worked or died: Graceland, Elvis Presley’s mansion; the site of James Dean’s fatal car crash in California; Robben Island where Nelson Mandela was incarcerated for 18 years. Whole towns and cities live off such disciples, from Jane Austen’s Bath to the French town of Descartes in the Loire valley, as La Haye en Touraine renamed itself in 1967 in honour of its famous son.

I’ve been on several such pilgrimages myself, usually to sites that are in themselves thoroughly underwhelming. When I first visited the place where Aristotle’s Lyceum once stood in Athens, it was just an excavation site behind wooden boards. Plato’s nearby Academy was not much better: an unloved municipal park with a few untended archaeological remains. Nothing of David Hume’s family home, Ninewells, remains in Chirnside on the Scottish borders.

Yet there is a pull to such places, one often rewarded with an emotional payoff. One of the most moving pilgrimages I’ve been on was a trip seven years ago to a craggy promontory in Norway on the small lake Eidsvatnet. This was the site of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s custom-built house near the town of Skjolden. It was difficult to find, hard to access, and all that remained were the foundations. But as I sat there and looked out across the water, I felt strangely moved.

On my return home, I learned of plans to rebuild the philosopher’s house – remarkably, it still existed. In 1958, it had been moved to the town and re-erected with modifications. The original windows were stored in a barn. At the time, reconstruction of the home in its original location seemed like a pipe dream. The Wittgenstein Foundation in Skjolden wasn’t even formally established until 2014. But in recent years the plan gathered momentum, helped by the owner’s threat to demolish it if it wasn’t bought from him. In March 2017, the county of Sogn og Fjordane and the local bank Luster Sparebank each gave a million Norwegian krona ($110,000) to the project. In May 2018, reconstruction began. Work was completed quickly. Jans, one of the project’s local builders, told me that, with these pre-cut timber homes, ‘it’s just like building Lego’.

The restored house.

I felt a strong desire to go to the inauguration this June. But I was also apprehensive and sceptical. How would it compare with my first visit? Would the reconstruction diminish the magic, making it feel more like a theme park? And why on Earth did I want to go at all? What is the point of secular pilgrimage?

Several factors conspired to make that first visit to Wittgenstein’s retreat magical. One was an element of serendipity. We hadn’t gone to Norway to visit Skjolden. But then neither had Wittgenstein. In October 1913, when he arrived at the Norwegian port of Bergen, he was looking for peace and isolation in which to work. It’s not clear where exactly he aimed to go, but the hotel he had in mind was closed for the winter. The Austrian-Hungarian consul then sent him to Skjolden, where he had business contacts. So it was by chance that Wittgenstein stumbled across the place that he would make a home away from home.

We were staying at a hostel in Solvorn, a short ferry crossing and a 22-mile drive from Skjolden. We knew that Wittgenstein had built his ‘hutte’ somewhere nearby and, when we discovered we could hire a car from the hostel owner, we decided to try to find it.

The good people of Skjolden did not make it easy. We were directed towards a campsite where a man pointed to a field, saying it was close by and easy to find. After several false trails and the help of two signs, one almost hidden behind vegetation, we finally found the unkempt, rocky path that ascended to the site. It emerged onto a clearing above the lake, the foundations clearly visible. We instantly knew why Wittgenstein had picked this spot. It was isolated and quiet, with a view across the lake to the mountains that were still dusted with snow in early June. It was the epitome of a place to retreat, think and write.

The view towards Skjolden.

The element of discovery helped to create the atmosphere. The path made it clear that this was not a place tourists flocked to en masse; it was ours alone for all the time we spent there. This gave it intimacy. We had, after all, made some effort, something Wittgenstein always approved of. ‘I should not like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking,’ he wrote in the preface to the Philosophical Investigations. ‘But, if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own.’

Even had the spot not been so wonderful, there would still be something powerful in the idea of standing where Wittgenstein once stood. That sense of connection is the constant in all secular pilgrimage. But where does it come from? Is it just romantic or mystical nonsense?

Wittgenstein placed his remote home where everyone could see it. He was an oddly ostentatious recluse

I don’t think so. Both the Universe and our existence are miraculous and bewildering in ways that we forget in everyday life. When you stand where others have stood years ago, the wonder of all this becomes much more apparent. Once there was a living, breathing, conscious Wittgenstein here, and that locus of experience has been extinguished forever. Today, I stand here but I too will go the way of all flesh. For millions of years, the world has been indifferent to this procession of conscious beings.

Yet this person who has long gone has left some kind of footprint. Not just the physical marks of the building he had constructed, but in the minds of millions. Words and ideas provide a very real and powerful link between the living and the dead. Through such links, we defy our cosmic insignificance.

However, it was only when I returned to the inauguration of the rebuilt house that I realised how much else of that sweet pleasure was constructed on fantasy. Take the romance of the site’s remoteness. We can imagine Wittgenstein crossing the lake by boat, winching up his supplies and water in splendid isolation. This plays to romantic stereotypes of the ascetic, monastic intellectual, cutting himself off from society to pursue his vocation. The local historian Harald Vatne concluded that the townspeople mostly found him cold and aloof.

But the reality is less straightforward. ‘If you want to be invisible, you hide on the other side of the mountain,’ says Harald Røstvik, a professor of urbanism at the University of Stavanger and a coordinator for the ‘One Life – Three Universities’ project linking Wittgenstein scholars in Berlin, Cambridge and Manchester. From the house’s balcony, he points across the lake to the town, saying: ‘If you really want to expose yourself to everybody, look at this. This is really visible.’ Wittgenstein placed his remote home where everyone in the village could see it. He was an oddly ostentatious recluse.

Nor was he really cut off. The lake is not large, and when it froze in winter, it could easily be walked across. When it got too cold, too wet or too lonely, Wittgenstein would often stay at Eide Gård, a farmhouse visible from his own abode. He never even lived in his own house for more than a few months at a time. Like Henry David Thoreau’s two years at Walden Pond in Massachusetts, Wittgenstein’s retreat from the world was more partial and dilettantish than legend would have it. Thoreau’s mother did most of his laundry and brought him food. His cabin was only a 20-minute walk from the family home, which he often visited.

Skjolden evokes an image of a philosopher of the wilderness, an iconoclast who rejects the herd. But very few philosophers were really like this. Many of the best were of the polis. Western philosophy has thrived in cosmopolitan Athens, Paris, Amsterdam and Edinburgh, places where the flow of people and ideas inspires creative energy. Hume liked to retreat to the family home at Ninewells but he also knew that Edinburgh was ‘the true scene for a man of letters’. Wittgenstein too would have been nothing were it not for his philosophical encounters in Vienna and Cambridge. Philosophy lives in the city. Isolation is just for restorative breaks.

Eidsvatnet lake, Skjolden, circa 1914.

By contemporary standards, early 20th-century Skjolden was not especially rural or remote. It was a hive of industry, a key port at the most inland point of the longest fjord in Norway. It was home both to a large ice storehouse and a lemonade factory. The grand Skjolden Hotel, where a feast dinner was held to celebrate the opening of the reconstructed house, was built in 1912 and held many of the large number of summer tourists. The sleepy, de-industrialised town of 300 residents today bears little resemblance to the busy place it was in Wittgenstein’s time. No wonder his peace would often be disturbed. One man who had the temerity to walk past his house was greeted by a furious philosopher yelling: ‘Now it’s going to take me a fortnight before I’ll manage to find back the thought I had before you disturbed me!’

Even the house itself is more romantic imagined than actually seen. English-speakers are tricked by the Norwegian word hutte, which has routinely led it to get called ‘Wittgenstein’s Hut’. When all we could see were its foundations, we could indulge our fantasies of simple, woodland living. But it is in fact a proper two-storey house that I could live in without any fear of discomfort.

The biggest illusion of Wittgenstein’s reclusion is that he was happy there. Sometimes, he felt too isolated, and there were a few months when he stayed at the nearby farmhouse as he was ‘frightened of the sadness that can overcome me’ in his own home. Alois Pichler, a professor of philosophy at the University of Bergen who has worked on the Wittgenstein archive, told me that he is convinced that Wittgenstein ‘was never really happy’. Granted, his last words were: ‘Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life,’ but, as Wittgenstein’s biographer Ray Monk points out ,‘wonderful’ is not the same as ‘happy’.

One of the reasons I admire Wittgenstein is that he models an ideal of the good life that is about much more than hedonic value. His was a serious life, lived with intensity, and so wonderful for him and others.

‘It’s the quiet and, perhaps, the wonderful scenery; I mean, its quiet seriousness’

The 1936-37 sojourn to Skjolden was a particularly serious one. Wittgenstein spent a lot of time reflecting on his ‘sins’, preparing confessions that he insisted close friends heard, often to their discomfort. Of these, the only ones we know are that he felt he allowed people to believe he was less Jewish than he was, and that, when he was a schoolmaster in Austria after the First World War, he hit a girl and then denied doing so. That these failings weighed so heavily on him says a lot about the moral seriousness with which he approached life.

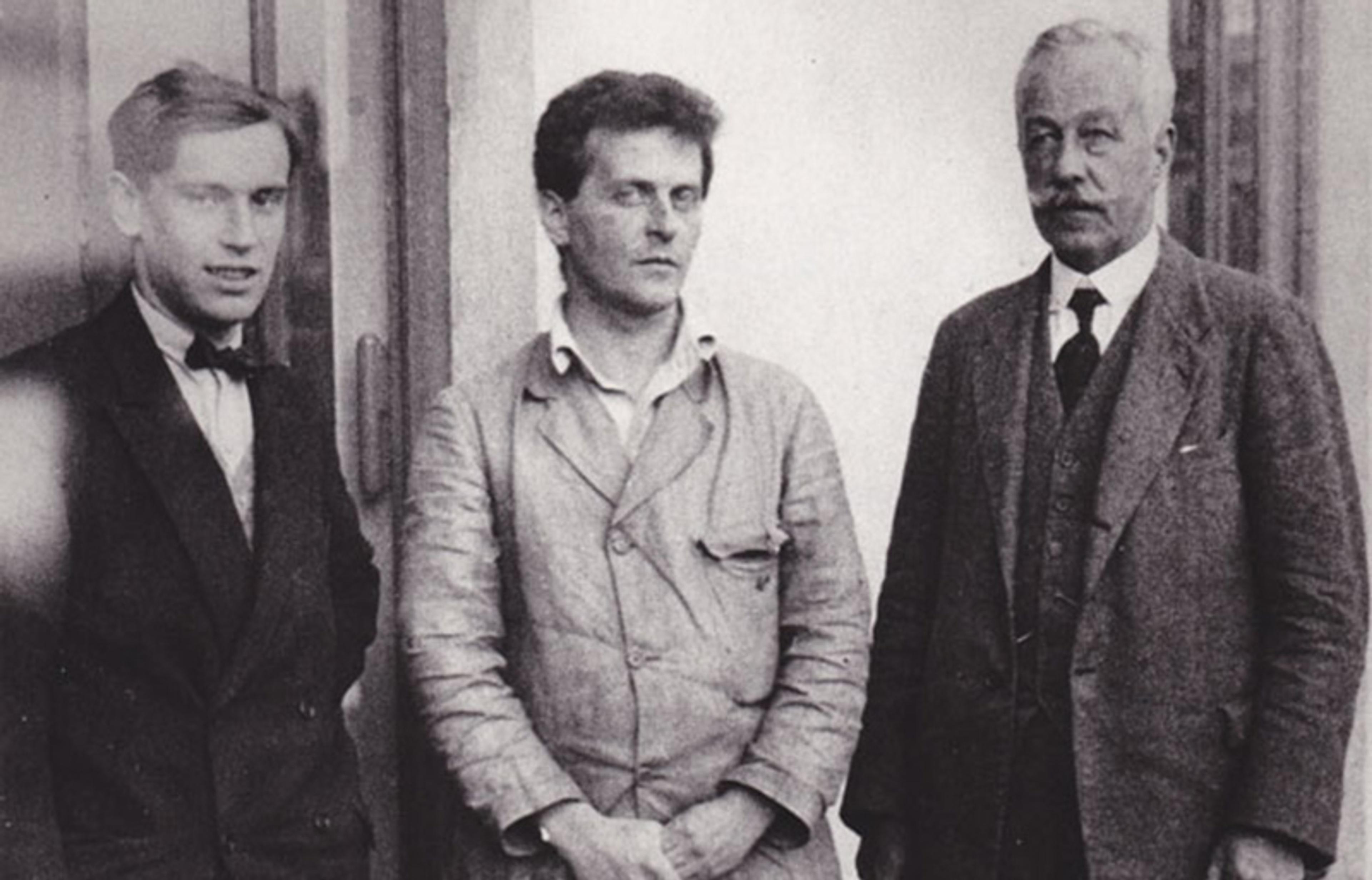

Wittgenstein with friends in Vienna, c1928. Photo copyright the Stonborough family

The blessing he got from Skjolden was not happiness but productivity. ‘I can’t imagine that I could have worked anywhere as I do here,’ he wrote in a letter to the English philosopher G E Moore in October 1936. ‘It’s the quiet and, perhaps, the wonderful scenery; I mean, its quiet seriousness.’ It’s a wonderful description of the Norwegian landscape, which has a beauty that’s never too gentle or easy, owing to the harsh winters and rugged geology.

Monk’s biography tells us that Wittgenstein had brought along some dictated notes, which came to be known as the Brown Book, with the intention of working them up into a book. By the beginning of November, he had given up, saying that ‘the whole attempt at a revision … is worthless’. So he started again from scratch and wrote what would become the first 188 paragraphs – around a quarter – of his late masterpiece, the Philosophical Investigations. According to Monk, it is ‘the only section of Wittgenstein’s later work with which he was fully satisfied – the only part he never later attempted to revise or rearrange’.

In the Brown Book, Wittgenstein criticised the view that words stand for objects, which meant he was also turning against the views he set out in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), in which words’ meanings were captured in mental pictures. Wittgenstein was sharpening up his new theory that the meaning of a word was given by how it is used. ‘Good’, for example, doesn’t refer to an abstract concept or nonphysical property of things. Rather, you know what good means when you know how the word is used in diverse ways and contexts.

Some comments in the preface to the Investigations suggest that what Wittgenstein brought to Skjolden was an unsettledness that was central to both his productivity and his new way of understanding language. He wrote that he had to give up his hope that his ‘thoughts should proceed from one subject to another in a natural order and without breaks’ and embraced a more fragmented reality:

This compels us to travel over a wide field of thought criss-cross in every direction.— The philosophical remarks in this book are, as it were, a number of sketches of landscapes which were made in the course of these long and involved journeyings.

Stepping into Wittgenstein’s actual home still leaves plenty of room for imagination to trick us into a bogus sense of intimacy. A few objects are said to be from the original house, including the bed. Standing in the small bedroom, it is too easy to believe that you can experience being there as he did. Time and context changes everything. How can a visitor just passing through today have any sense of how this room felt to a man who lived there a century ago?

To gain any real understanding from such physical remains, you have to study and pay attention. Røstvik points out the metal corner brackets that hold the window frame together. Traditionally, these would have been ornate but Wittgenstein’s were plain, ‘very minimalistic’. That’s just one of the ways in which he sees Wittgenstein’s ‘fingerprints’ on the building. Interestingly, Wittgenstein made the building Austrian rather than Norwegian in character. The shutters flap out rather than open inwards. The roof slopes down to the front rather than to the side of the house. (When it was moved in 1958, the new owner actually rotated the roof 90 degrees to correct this Austrian aberration.) This is more evidence that Wittgenstein was no retiring recluse but someone who deliberately made his mark on this corner of Norway.

The experience of visiting the house is certainly enhanced by the knowledge that what you see is identical to what Wittgenstein saw: 90 per cent of the hutte is from the original. It is more authentic than most cathedrals, which have been renovated and adapted over the centuries.

The contrast with Thoreau’s cabin is striking. That is a reconstruction, faithful to every detail. In gives you a better sense of exactly how it was when Thoreau stayed there than Wittgenstein’s house does. But knowing it is a reconstruction changes the experience. The physical link creates a thread through time that connects us directly to the people of the past. It seems that authenticity of substance matters more than authenticity of form. Better the original ruins of the Pantheon in Athens than a more complete simulacra.

The building’s return to the site had evidently added something. But does it also take something away? In its abandoned state, this was a place of genuine pilgrimage. Now it threatens to become a tourist destination. For devotees of Wittgenstein, this is a terrible irony. He never had anything good to say about tourists. They were not welcome at his talks. The American philosopher Norman Malcolm’s memoir recalls Wittgenstein saying: ‘My lectures are not for tourists.’ Even his visits to Skjolden were timed to avoid the summer tourist season.

Wittgenstein would have also surely disapproved of how restoring the house clings to the past rather than lets it go. At the end of the Tractatus, he wrote:

My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognises them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)

Wittgenstein was talking about the process of learning and the function of philosophy. But these words express a broader ethic. We should always be looking forward, leaving behind the things that have got us thus far, in order to make room for whatever we need to take us on the next steps. His hutte served its purpose. Why bring it back from the dead? If we really admire Wittgenstein, why be so concerned with the past when he wasn’t?

Freud’s house in Vienna has become a tidy museum that has lost the feel of a working building

The question deserves an answer because the heritage industry is not done with Wittgenstein yet. The Wittgenstein Institute in Vienna wants to open up Haus Wittgenstein, built for his sister, Margaret. It is often said that Wittgenstein designed the modernist building. Although many of the details are his, according to Røstvik he only made modifications to the architect Paul Engelmann’s plans. It’s currently the cultural department of the Bulgarian embassy and not usually open to the public. Glimpsing parts of it over the high walls surrounding it left me wanting to see more, but perhaps some desires should not be indulged.

There is little doubt that the prospect of tourism is what finally got the Skjolden project funded. Appeals to the Austrian embassy and to Trinity, Wittgenstein’s old wealthy college at Cambridge, were fruitless. In the end, the lead funding came from local authorities. Ivar Kvalen, the mayor of Luster (Skjolden’s municipality) was enthusiastic about the house’s potential to draw visitors. ‘This is going to be big for tourism, and for Wittgenstein scholars,’ he told me. ‘For the last 20 years, you see the increased interest in Wittgenstein in Luster. People come from all over the world to visit this site.’

While the project is locally driven, it’s not because of tremendous local interest. ‘It’s almost more international than local,’ says Jan, one of the builders. ‘Local people don’t understand how big he is in the wider world. Here they don’t call it the Wittgenstein hutte but Østerrike,’ Norwegian for ‘Austria’.

The complaint that tourism ruins precisely what attracts people in the first place is of course old and familiar. But it is especially true of pilgrimage sites. The feeling of some strange intimacy over time is central to the experience, and this is lost whenever crowds or excessive ordering impose themselves. I felt this at Sigmund Freud’s house in Vienna. Knowing that this was the room where he saw his patients and developed his theories certainly had an effect. But the place has become a tidy museum that has entirely lost the feel of a working building. The display panels and other visitors made forging the imaginative link between what is there now and what was there then impossible.

In contrast, a few brief minutes alone at the foot of the stairwell in the Turin apartment block where Primo Levi fell to his death felt poignant, despite my unease over morbid voyeurism. With no ticket, no souvenirs, no parade of people off cruise ships, it felt like a genuine moment of paying respect, and an opportunity for silent meditation on the horrors Levi endured, and the beauty and wisdom wrought from them.

When the English writer Lesley Chamberlain visited ‘Østerrike’ in 2011, she mused:

tourism doesn’t easily wrap itself around artists and intellectuals without smothering their strangeness. What is needed is of a different order: a stunningly fresh idea to link difficult philosophy, intransigent genius and one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

Whether the reconstructed house can deliver on this remains to be seen. The ‘One Life – Three Universities’ project offers some hope that this might yet come to pass. ‘I’m uncertain if Wittgenstein would have loved us standing here,’ says Røstvik. ‘It’s a relic. Does he want that kind of attention? We don’t know. But what I’m pretty sure he would have found interesting is that students and teachers from three universities he was at are here meeting and discussing.’

If the house on the lake can become a new iteration of a philosophical retreat, that would pay homage to its first owner much more than any number of selfie-snapping visitors could.