Once there was a world without power. No power stations, power surges, or power suits. A world in which, okay, people ruined their eyesight sewing stuff in the dark, and had the occasional accident on the stairs. Indoor plumbing still had a way to go, too. But at least our genes and gonads weren’t permanently damaged by manmade radiation leaks, and nobody ever found themselves in a multi-vehicle pile-up. They were spared so much, our ancestors — mowing the lawn, struggling with the twin tub, driving children to piano lessons… They had it all — freedom, individuality, culture. They even had some spare time, in which to think. And then electricity was tapped, Henry Ford discovered the source of the vile, and Steve Jobs handed Eve her Apple.

Some shreds of civilisation survived into the 19th century. Recently I went to see an exhibition of Japanese silk embroideries at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. They were probably not the best embroideries ever. Instead, they seemed to represent an odd cul-de-sac in the history of decorative arts; painstakingly composed of millions of brightly coloured stitches against black backgrounds of silk or velvet, they were mostly made for immediate export, to please Victorians in England, America and elsewhere. Many of them were frightful, pictorially, using excesses of silk and gold thread to produce dead, touristy records of a hillside temple or a tiger. One triptych screen of a life-size embroidered peacock offered the closest approximation of peacock feathers that I’ve ever seen. But it’s still not a peacock, and it was hard to see the point.

Maybe you have to sew a hundred vulgar panels to come up with one good one: padded silk is an art form I’d never fully recognised before, and one folding screen showed tiny labourers, village characters and fancy ladies, meticulously rendered in relief, every detail of their garments made hyper-real. It was stupendous. But even when grotesque, these textile efforts have a dignity and verve that most printed images and photography lack. They exist, they co-exist with us, they age, they breathe. They were very cleverly, sometimes beautifully, put together by hand, many hands (mostly male hands, in this case) a century ago. Part of what’s compelling about such handicrafts is the thought of how much life had to be lived just to get the thing done. Time was invested in these peculiar products. It begins to seem quite tolerable, silk embroidery — and no electricity was involved.

With technology, industrialisation, and their bedmate, alienation, we’re not just losing sight of what art is, but of what the human hand can do. It’s capable of a lot more than just gliding a mouse around or struggling with Velcro. As James Joyce said about the hand that wrote Ulysses: ‘It did lots of other things too.’ Hands are great. We wouldn’t last a minute without them. Nobody would catch you when you’re born, or affix you to the nipple, or change your nappy. No matter how much we like computers, consumerism, and sitting motionless in front of the TV, the human hand is our biggest love. Not to see anything made by hand, on a human scale, is a kind of death — like the prospect of never being touched again.

I am tired of electricity, gas, petrol, and nuclear power. I’m just sick of any energy other than the kind plants and animals naturally expend going about their daily business. I’ve begun to search the world for anything that doesn’t require electricity: wrinkles in clothing for instance, because they imply an iron lying fallow; dust bunnies under beds — no Hoover about to hove into view. I’ve come to see electricity as a kind of ethereal rapist, that can’t stop interfering with everyone: gas and electricity insinuate themselves into the house, and the money drains out of the bank. It’s a form of abuse.

We’re not given any choice in the matter. Having no electricity has long been regarded as an embarrassment, a sign of poverty or incompetence, and the stigma has cajoled most of us into believing we must have it. Hydro-electric companies are always throwing people out of their homes to build dams, so as to provide the same uprooted people with electricity in houses they don’t like very much, but where they can now read their electricity bills by lamplight. And we seem convinced we must use up as much electricity as possible, before developing countries get their mitts on it.

Just thinking about anything unelectric fills me with a warm, private, low-tech, halogen-free glow

It’s grown on me gradually, like a tortoise shell, that I hate electricity. The more I see and hear of it, the less I like it. This only recently solidified into An Opinion. It’s not really a moral position, nor a political one, though there are ways of defending it with moral and political arguments. It’s not exactly melancholic either, derived from news on the state of the environment — though I am melancholy about the environment.

No, my aversion to electricity began, as far as I can trace it, in reaction to finding out, when I was 12, that Lake Erie was officially dead, flooded with toxins from factories on its shore, and that not a fish could live in it anymore. This was the late 1960s, so my solution took the form of a vague lifelong hippy notion of getting back to nature, manifested in a disdain for fashion, gadgets, new buildings, the space programme, men with short hair, pharmaceutical companies, witch-burning and the Industrial Revolution.

But I’ve recently started observing in myself a disgust with all things buzzing, humming and zapping, and a definite increase in my allegiance to simple stuff that doesn’t move without help, stuff that just sits there, stuff that doesn’t require the aid of power stations to validate its existence. It might have originated in factories, or through various uses of fossil fuel, but it has since rebelled against this parentage and claimed its own quiet, independent life. These things include: toilets, bicycles, butter, jam, keys, buttons (NB buttons and zips are actually a kind of key: they open and shut your clothes for you), belts, plasters, blankets, books, pens, pencils, paper, shoes, sheds, sleds, skis, skates, bells, wind-up clocks, musical instruments, typewriters, wooden tools and hand-powered gardening implements, cutlery, clothing, Kleenex, needles and cotton, corkscrews, cigarettes, doors, door knobs, candles, see-saws, tennis rackets, tulips in a glass of water, (non-electric) toothbrushes, Japanese padded silk panels, cupboards, tables and chairs. Just thinking about anything unelectric, ungaseous and non-nuclear fills me with a warm, private, low-tech, halogen-free glow.

The shutters in my bedroom, which keep out the light and the cold, were probably created without the use of power tools, and are now manually operated. A human being has to effect any change in their position. No other force, no artificial, doomed or dwindling power source, is involved. And they work! The duvet works too, without electricity, as do the cupboards, shelves, floorboards and rug. So too the pictures I love on the wall, and my husband, who runs on his own steam, especially when steamed about something. It’s a simple pleasure, but I like the fact that you can open and close our bedroom door without having to enlist the services of the National Grid.

But there are lamps in the room, too — though not as many as a friend of mine would advise (she always says I have too few lamps, while I think she has too many: she makes no allowance for my aversion to electricity). There’s also a laptop, and an electric heater. These things jar.

I haven’t yet reached so extreme an aversion that I have to retreat to the desert or up a tree. There are fluctuating levels of electricity-tolerance, I find. On a plane, for instance, you (resentfully) surrender to everything: the suck-you-uppo toilets, the microwaved meals, the little reading light, the fake fan that pretends to offer you a gust of actual air, the seven hours straight of staring at the screen in the seat in front of you in search of ‘inflight entertainment’. But at home I flee from these things towards the stable, non-buzzing, non-blasting, non-depleting properties of the unelectric: endearing entities like husband, table, scissors, paper, stone. I’d give anything not to have to hear an extractor fan ever again.

Why do we find shiny computer screens so compelling? We can’t help looking at them. I think they’re like windows. We instinctively keep an eye on them, as if by doing so we’ll be able to fend off marauders or make better weather predictions. Glittering glowing colours have always enchanted people, no doubt reminding us of fire — another ancient love. But computer screens aren’t actually all that warming. You can’t cook anything on them, they don’t keep enemies at bay, and they’re not even as much like stained glass as we might romantically hope. They’re prison bars. For each computer screen, its prisoner. There are now a billion personal computers worldwide; according to wiki-answers.com, in another two years there will be two billion.

I have fantasies of electricitylessness. To live in a steading somewhere, equipped with a reliable well, vegetable patch, fireplace, maybe a wood-fired Aga. Cold white wine would somehow emanate from its own spring just outside the door. Inside, it would be all porridge and patchwork quilts, padded silk hangings in progress, a chicken or two, and musical instruments, which we’d play to warm ourselves up. Yes, I would miss the ready supply of the finest music, now provided instantly by free music streaming. And washing clothes by hand would be a chore. And it’s easier to fill a hot water bottle if you’ve got an electric kettle. Many household machines, I admit, are useful — cookers, dishwashers, fridges, freezers, toasters. But they take up so much space! If only they could be merged into one do-it-all mechanical slave that charges around your house vacuuming, toasting, and broadcasting non-stop. Cooks up a stew too, once it gets hot enough. Dutifully obeying the modern principle of agglomeration, it would be called an iPlod.

The noise generated by these machines of ours! A typewriter isn’t silent, I know, but it sure beats a washing machine on spin cycle. Noise is a new fetish with us. Why rake leaves quietly, allowing neighbours to sleep late, when you can frazzle everybody’s nerves with a leaf-blower? Why sweep the streets manually with brooms when you can send out an ineffectual (but expensive) little mechanical pavement sweeper with a cutesy name, that offers not only the delightful sounds of twirling brushes and suds squirters, but a vexing electronic voice that repeats the command ‘Attention. Take care, pavement cleaning in progress’ all the way down the street? (Though from afar it sounds like ‘Buzz off buster, buzz off buster, buzz off buster…’)

I recognise that I’m fighting a losing battle, since everything is becoming more and more electric. Even I am: I started writing this on my typewriter, yes, that grand old invention that prints automatically, never needs updating, and costs almost nothing to run. Mine is second-generation. It belonged to my father, weighs about 40lbs, and has very small type, which I particularly like. But here I am now, like everybody else, tapping out a Word Document on a laptop, with Pieter Wispelwey playing Bach suites for solo cello to me on the same machine. What will happen when every good, plain manually operated mechanism is replaced with an electronic one? We’re already being offered electric toilets, and key cards are standard in hotels and universities. Maps have been outmoded by SatNav, books by Kindle, Nook and Kobo, while playing cards, Scrabble, crossword puzzles, shopping, and gambling are usurped and exploited by online enterprises.

We revel, we wallow, in our dependence on electricity. But what about power cuts? After the Halloween hurricane of 2012, people in New York couldn’t use the lifts, had no water supply, the food in the fridges rotted, and dialysis had to be rationed. We’re completely at the mercy of energy-providers. We (not those of us on dialysis naturally) have given up our freedom and any remnant of self-sufficiency to become mere consumer units that purchase electricity. We exist only to establish more and more outlets for electricity, and to make more requirements of it.

It would be wonderfully calm and quiet in our steading, and so private. Every time I use a computer I feel like the advertisers and the FBI are staring over my shoulder.

Electronics are high-anxiety, high-maintenance luxuries. The cost alone! Computer companies have had a bonanza on built-in obsolescence. We all have to invest thousands of pounds updating our IT equipment every few years, just to get our emails. Real enthusiasts exult in these updates, but letters barely exist anymore, edged out in favour of internet communication. Our entire culture is fly-by-night — all in the service of electricity. It doesn’t serve us, we serve it.

Everywhere, the physical and the manual are being obliterated in favour of the virtual, which is far less cherishable or charitable. Reading an ebook might be convenient, but you’re submitting to a kind of sensory deprivation: you don’t visually remember the page the same way with a Kindle, you don’t get the smell of the paper, and you don’t know by feel how much you’ve read (the machine has to inform you coldly that it’s three per cent).

We think of ourselves as bathed in light, artificial light. We worry vaguely about ‘light pollution’ from office blocks and street lamps, and whether it can be seen from space. But we’re really back in the Dark Ages. No trace will be left of our culture soon but climate change, Nigella Lawson mixing bowls, the Gutenberg project (which still doesn’t have any of the books I want), and radioactive waste. There’s still no sensible, responsible or bearable plan for dealing with the by-products of nuclear power stations, much less with nuclear disasters, or terrorist plots against power stations, and nearby earthquakes. I’d rather walk to London than take a train fuelled by nuclear energy, our government’s latest thrill-seeking plan. But we are like kids with their toys: we want cars and computers and every type of gadget that uses up power, and we want them now. It’s all a big game to us. Entranced by every form of unreality we can find, we’ve lost contact with the earth itself. We’re collectively, impetuously, unthinkingly, mesmerically, floating off into cyberspace. The insects will be pleased.

And just a few hundred years ago the world was so verdant! It was there to be loved. Before the Industrial Revolution, despite religion, war, despotism, colonisation, anaesthetic-free surgery and terrible pasties, there was still some humanity, even humility. Look at Tobias Smollett, writing in The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771):

Glasgow… is one of the prettiest towns in Europe; and… one of the most flourishing in Great Britain… From Glasgow we travelled along the Clyde, which is a delightful stream… Here is no want of groves, and meadows, and cornfields…

Things were still beautiful, before the hatred of anything natural took us over. Okay, so there was no whooping cough vaccine. But there was a lot more clarity, not just in the air and the water, but in people’s minds.

This world is too expensive, too ugly, too heartless, too handless. Where’s art, where’s humanity, where’s comfort?

Now we go to war over oil! Is it really worth killing for? People still regard car travel, if not as a pleasure, then as an unavoidable obligation. They only complain about fatal motorway crashes when they cause traffic jams. Driving seems like hell to me, and such a waste of time. The furious and anxious hours spent tediously negotiating your own individual vehicle round all the other ones, the honking, the servicing, the insuring, the parking, the taxing, the vandalism, car theft and car-jacking, calling the AA, getting petrol, buying the car in the first place, and reading about car makes. The noise of motorways has by now ruined almost every rural idyll. The zooming and blinking and the buzzing, the buzzing!

What’s wrong with skis, which are essentially a sort of self-powered train that comes with its own tracks? And there’s the bicycle. You don’t need the Olympic cyclist Bradley Wiggins to tell you that moving along, suspended on a little seat with the wind in your hair (or helmet), is a pleasant sensation. You can park it anywhere. It moves at a manageable, human pace. In Mike Leigh’s film Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), Poppy is totally contented on her bicycle — until it’s stolen. This leads to her learning to drive, a decision full of unforeseen hassles: not only are her high-heeled boots not really up to the job, but her driving instructor is insane. Trundling through London with him in her metal polluting box, she loses touch with the world.

Maybe we need to use all the remaining electricity to manufacture bikes, and then turn it off.

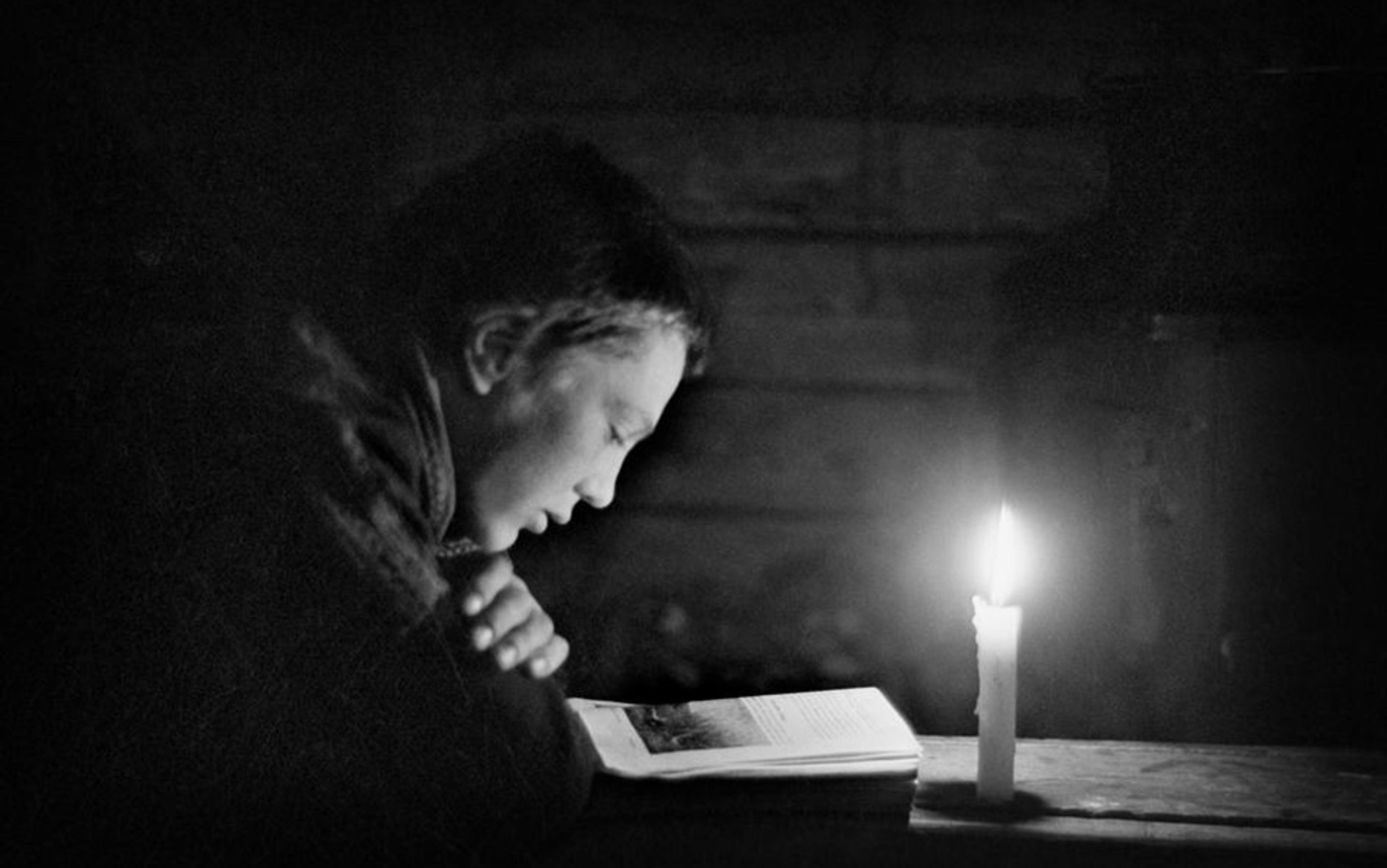

You know what works without electricity? Nighttime. We survive hours and hours of electricitylessness at night (unless you’re dependent on an electric blanket or iron lung). You can sleep right through these low-tech periods of darkness, or go for a walk. You might fall occasionally, but with any luck you’ll see some stars. And other people. They’re not electric yet either — but they’ll probably soon be replaced with robots out on ethnic cleansing missions, so enjoy real people while you can.

This world is too expensive, too ugly, too heartless, too handless. Where’s art, where’s humanity, where’s comfort? Where are the simple, amiable, graspable products of our labour? All I’m saying is that when the primordial shit hits the electric fan and all current sources of energy are kaput, I will still have my books, pencils, paper, needles and thread, socks, slippers, long johns, a loo, a toothbrush, a typewriter, some candles, and a wind-up torch. I hope. What about you?