Listen to this essay

23 minute listen

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

– from Profiles of the Future (1973) by Arthur C Clarke

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature.

– from ‘The Deepening Paradox’ (2011) by Karl Schroeder

In Indra’s Net of pearls and jewels, every gem reflects every other, a shimmering image of interdependence. This ancient Vedic metaphor for connection across the cosmos also illuminates what the environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht first proposed in 2014 as ‘the Symbiocene’: the era after the Anthropocene, in which human technologies take their cues from living systems and work in partnership rather than through dominance. The term ties technological curiosity to biophilia – our love of life – so that what we make is shaped by the living world we belong to, until the boundary between the built world and nature begins to soften. If the Anthropocene began when the Industrial Revolution set industry against the living world, the Symbiocene imagines what should follow: interspecies democracy, life within Earth’s limits, and ecological reciprocity. This is not a future where we engineer nature to fit human comfort and convenience. Instead, creation becomes a conversation: a turning away from our long habit of using technology against nature, toward listening, humility and the flourishing of life.

But how do we loosen modernity’s grip when we’re still dependent on its tools? The answer is solarpunk, the edgy but sincere cultural movement joining technology with nature – reimagining technologies based on conceptions of science that coax rather than torture. The ‘punk’ in solarpunk comes from its blended roots: not rejecting technology like a luddite, nor blindly embracing it like an ecomodernist, but instead yoking technological development to ecological and biological principles to serve the good of the whole. The ‘solar’ element connects the photosynthetic wonder of plants as light-eaters, with the free energy of the Sun harnessed by solar panels and other forces of nature in wind, water and geothermal energy.

Solarpunk’s point isn’t that a ‘solar future’ begins and ends with the devices we already know. It widens the meaning of technology to include Indigenous and place-based practices such as chinampas – raised garden beds woven from reeds, anchored in shallow lakes, and refreshed with nutrient-rich silt from canals. They don’t produce electricity, but they do produce abundance: food, soil and a stable local ecology. Solarpunk puts that kind of low-energy, high-yield ingenuity beside high ecotech like atmospheric water harvesters to pull drinking water out of the air, and regenerative microgrids to store power. In other words, it treats science and technology as plural: shaped by culture, landscape and values, not dictated by a single industrial blueprint. That’s why solarpunk often turns to biomimicry – learning from nature’s designs – to aim human ingenuity at repair: restoring ecosystems while also restoring the ways we live with one another.

A solarpunk values map, where eco-centric and human-centric aims overlap. Courtesy Day Sanchez/ Solarpunk Generation

Think: dirigibles drifting above rooftops, solar panels that repair themselves, permaculture and agroecology – growing food by designing farms and gardens to work like ecosystems, where soil is rebuilt, water is conserved, and ‘waste’ becomes nutrient – meals from what you and your friends helped grow, holograms that ease the glare of screens, and a life measured less by shiny throwaway objects than by shared experiences. The point is not ecology or technology, but the refusal of that split. In its queer and eco-anarchic streak, boundaries stay permeable, hierarchies stay suspect, and the world is understood as a set of overlapping relationships rather than sealed categories. From there come its cultural commitments: inclusivity; post-scarcity (the idea that society can meet everyone’s needs); and post-whiteness, meaning no single culture gets to define the default future. Against capitalism’s manufactured inequality, it sketches a more porous way of living, modelled on nature’s interdependence. In that wider frame, truth-telling becomes possible again, long-held wounds can start to heal, and humour returns – not as denial, but as the relief of not taking ourselves, or our tools, quite so seriously.

If oneness with nature is our evolutionary inheritance, and rising above nature our post-Enlightenment present, then solarpunk imagines a future back in balance. It keeps what technology makes possible, but redirects it toward meeting real needs while cooperating with the living world. The ‘solar’ in the name matters here. It suggests power that is abundant, gentle and shareable, and it carries a simple claim: the good life does not have to be complicated, wasteful or built on someone else’s loss.

To get an aesthetic sense of the technologies, watch this solarpunk-inspired commercial, retouched – in classic solarpunk fashion – to cut the dialogue and remove all branding

One way to see this more sharply is to set it beside steampunk, the retro-futurist movement that romanticises an age of steam, adventure and machines still simple enough to mend by hand. For solarpunk, that affection for repairable tools carries over, but the values shift. Here, landscape planning, architecture and infrastructure are treated as ecological questions, not just engineering ones. Progress is measured by peace and sufficiency, and by technologies that strengthen communities, protect the commons, and make everyday life more durable.

The solarpunk flag, with the half-gear representing technology compatible with nature and the sun representing the infinite potential of the open imagination – futurism guided by deep sustainability. Courtesy Wikipedia

Self-sufficient cities, fostering health through clean air, water and lush botanical features, have appeared in futuristic visions for decades. Visual representations harken back at least a century to futurists sick of black soot, utilitarian architecture and industrialisation’s pollution sapping the beauty from buildings and the people who lived in them. As housing and architecture itself became industrialised and mass-produced, local flavour evaporated, and the patience to evoke beauty was lost. In the postwar period, it wasn’t only the Soviet Union where ugly block buildings took over. As cement and pre-fab became the tools of the global trade, cities became designed for cars, not humans, and buildings reflected this loss of connection to beauty and nature. Urbanisation at the expense of liveability not only harms our health and dampens the idyllic rus in urbe (bringing the charms of the countryside to the city), it also kills the spirit.

Solarpunk shifts the aesthetic, challenging the austere utilitarianism of the factory and the modern built world. In their place, it ushers in a thriving but not grasping economy; decentralised direct democracies; and nested, loving communities. Nature is treated as a commons. Work is shared and playful, and play productive. Significant leisure time follows the rhythms of pleasure and rest, and doting on nature stewards our nervous system and habitat. The result: a-leave-no-trace ethic, where beauty, health and ecology form a golden braid, civic peace ignites merry prankster creativity, and the priority is a meaningful life.

Solarpunk is just one way of picturing the Symbiocene, where human invention takes its cues from living systems rather than working against them. But the solarpunk movement predated the idea of the Symbiocene itself. Long before Albrecht proposed his replacement for the Anthropocene, before ‘solarpunk’ was even a label, designers and writers were sketching ecologically grounded cities and asking what it would mean to make the built world hospitable again.

One early and unusually concrete voice was the urban designer Richard Register, who laid out, in words and drawings, what a solarpunk-like future could look like in his book Ecocity Berkeley: Building Cities for a Healthy Future (1987). His basic claim was that car-centred cities could be redesigned as ecocities. He challenged the defaults of modern planning while treating the city as an ecosystem of bodies and behaviours, not just roads and buildings. In that spirit, ecologically minded architects (sometimes calling themselves ‘ecotects’) and futurists rallied around the concept. Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia (1975), Christopher Alexander and colleagues’ A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (1977), and Starhawk’s novels The Fifth Sacred Thing (1993) and City of Refuge (2015) are among forerunner works by Global North visionaries. Many of their ideas ran into real-world gridlock in planning meetings and zoning hearings, and the energy increasingly shifted toward art and story: imagining the worlds that institutions would not yet permit, as in Ursula K Le Guin’s novel The Dispossessed (1974).

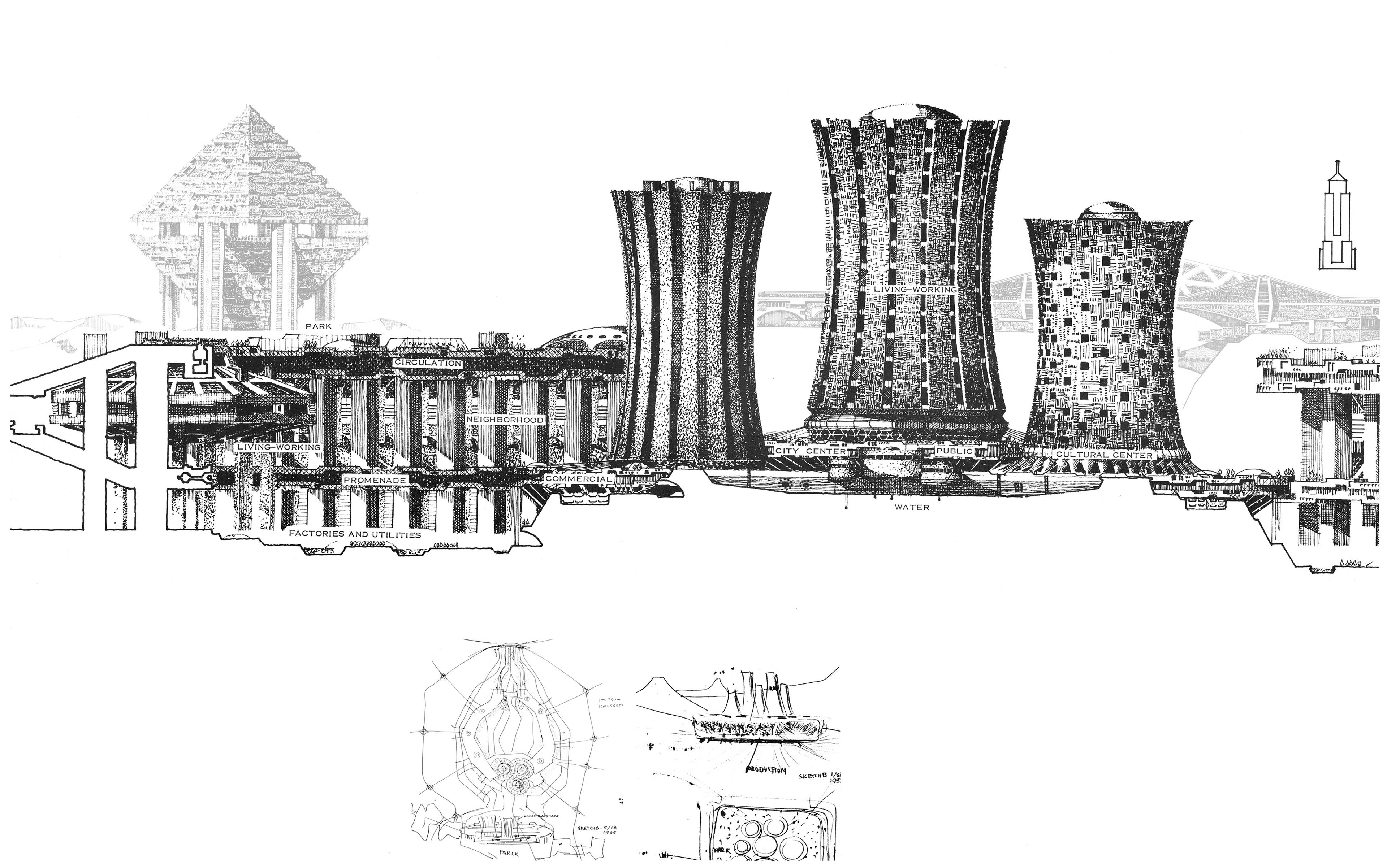

Then there is the Italian American architect Paolo Soleri, who proposed ‘arcologies’, a blend of architecture and ecology. He pictured towering, self-contained cities meant to behave like ecosystems rather than factories. The aim was not power concentrated in glass-and-steel monuments, but land conserved through density so that large areas could be rewilded. When the video game SimCity 2000 in the mid-1990s introduced a secret level based on arcologies, the concept briefly stepped out of architectural theory and into popular imagination.

While cottagecore looks back, solarpunk looks ahead, presenting us with a blueprint for the future

By the 2010s, solarpunk had emerged as a green reimagining of steampunk. It also arrived in dialogue with cyberpunk, the high-tech/low-life genre of neon dystopias where corporate power, surveillance and alienation dominate. Solarpunk retains the freedom-loving DIY elegance of both genres but, rather than capitulating, it synthesises them with a green brand of anarchism. Movies like Black Panther (2018) and its solarpunk city Wakanda have since brought this futuristic eco-integrated technological vision to the masses. Japan’s Future Design movement, depicted in Roman Krznaric’s book The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World (2020), has also fed the solarpunk stream. And Amsterdam’s new solarpunk architectural projects include a designated speaker for the rights of the more-than-human world on its decision-making board, straight out of Starhawk’s Fifth Sacred Thing (we’re getting there, people!)

DALL-E imagines a solarpunk Barcelona. Courtesy prlz77/X

On a more metaphysical level, the Potawatomi conservation biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (2013) brought to the world stage the question of what ‘becoming indigenous to a place’ means, and linked activism with a grounded vision of the future. Solarpunk provides one vision fulfilling that promise by moving from an extractive disposable economy to a bioeconomy of composting, where materials are designed to return safely to soil instead of needing fire to melt, smelt or incinerate them back into use. One pop-culture glimpse of this appears in the film Transcendence (2014), where Johnny Depp’s character designs technologies that draw molecules from the environment to regenerate and self-repair after he is uploaded to the internet.

Solarpunk also has something in common with the cottagecore movement, which imagines an idealised collective pastoralism. Both cottagecore and solarpunk are committed to the beauty and at-homeness of living in a healthy, alive and playful ecology; such a society places care where it matters most. But while cottagecore looks back, solarpunk – today solidly under the umbrella of ecofuturism – looks ahead, presenting us with a constellation for the future with which we can experiment.

Solarpunk art by Imperial Boy

Ablution by Thomas Chamberlain-Keen. This solarpunk concept art was created for the Cubebrush Worlds 3D environmental art competition, focusing on realistic design elements for a sustainable, futuristic floating city built within engineered megaflora that purifies water. Courtesy Thomas Chamberlain-Keen

Imagine a society where the goal is to develop our ecological intelligence, which feeds our emotional intelligence and vice versa in a virtuous loop. A society that ignites regeneration, where work and play become one, where we live close to the land (even if it’s in a sky-touching arcology), because we have rewilded everywhere skin-in and -out with the analytic intelligence of permaculture, agroecology and integrated pest management so that we find curated lushness wherever we live. As the researcher Adam Flynn put it in ‘Solarpunk: Notes Towards a Manifesto’ (2014): ‘Solarpunk is a future with a human face and dirt behind its ears.’

One of the most provocative ideas I’ve been exposed to through solarpunk is the YouTuber Andrewism’s notion that liberated forms of genetic engineering and genetically modified organisms (GMOs) could be used to create ‘bioluminescent trees to light our streets’ or ‘bamboos as strong as steel’, potentially working with, rather than against, the organisms we modify. (Getting consent from those organisms is another question that remains to be answered.) However, as Andrewism urges in the video ‘How We Can Make Solarpunk a Reality’ (2021): ‘GMOs can only be solarpunk if they work to empower people and the environment, not corporations.’

I admit I felt triggered when I first heard Andrewism (aka Andrew Sage) suggest that solarpunk could include GMOs. As a plant philosopher, I’ve researched their origin in support of pesticide sales and the billions spent by agribusiness to manufacture what I felt was a fake consensus around their safety. Nonetheless, I believe that, if we truly got to a solarpunk future with our technologies so integrated with nature, what it would mean to genetically modify an organism would itself change completely – maybe no genetic modification from our part would even be necessary if we just let the new ecologies we curate do the work of creation instead.

A lush vertical neighbourhood where cables, roofs and balconies double as gardens – an improvised, nature-threaded cityscape. Note this rendering of solarpunk comes with a dinosaur in the streets (de-extinction) and a flying, steam-powered insect vehicle; digital illustration by the Chinese artist Trylea (aka Zhichao Cai). Courtesy Zhichao Cai

Solarpunk is about imagining what the world could look like if we used technology and labour to improve all lives, instead of concentrating wealth for the few. The aesthetic, which in some instances might feel lower tech than current technologies due to our mechanistic conditioning of what technology should look like, is about finding the local equilibrium of funky sustainability; and that requires freedom from the profit motive. In solarpunk, technology is yoked to the good life across interspecies contact, based on mutual aid, community flourishing and trust.

Recently, a number of ecofuturist proposals have been put forth – but all seem to miss the solarpunk ideal. For instance, in 2017, Sidewalk Labs, Alphabet/Google’s urban-innovation arm, explored a smart-tech approach for the Quayside waterfront project in Toronto, but it ran aground amid public backlash and political resistance. Rejecting the high-tech, sterile, sensor-filled Googlelandia, Toronto locals argued for a city shaped by democratic control and lived-in place, not corporate data-collection and optimisation. Many wanted a more organic urban experience that evoked a stronger sense of place, or terroir.

People want to live in cities for the vibrancy, at times the chaos, not to be drones under a sterile but efficient dome

Another vision for the future is Saudi Arabia’s planned new city Neom (from ‘neo’ + the Arabic mustaqbal, meaning ‘new future’). In its imagery, Neom comes closer to solarpunk than to Toronto’s Quayside, but it still shies away. Envisioned as a 1 trillion Saudi riyals ($270 billion) linear megacity in the desert – with twin mirrored walls rising 500 metres (1,600 feet) and stretching along some 170 km (105 miles) – Neom would have capacity for 9 million people. It promises zero emissions, vertical farms, no cars and no pollution – notwithstanding the enormous material and ecological costs of constructing such a project. Backed by a sovereign wealth fund and driven from above, it borrows solarpunk’s look more than its values. The difference isn’t aesthetic; it’s moral and political. In a project like Neom, scale comes first, and whatever stands in the way can be treated as collateral. In solarpunk, it’s the non-negotiables that come first: consent, shared ownership, and a built world that can be maintained by the people who live in it. Solarpunk is based on composting and no waste: things are meant to last, be repaired, and return safely to the world when they’re done. Building self-repair into tools undercuts planned obsolescence and the churn of replacement. Solarpunk’s ingenuity assumes a steady-state economy that cools the fever dream of endless growth; Neom doubles down on it.

Courtesy Neom

The contrast clarifies what many people are reaching for instead: a city that feels alive, not merely optimised. One emblem of that desire is the Toronto Tree Tower, a proposed low-tech high-rise wrapped in vegetation and natural materials, designed to bring nature back into the everyday fabric of the city. As its architects put it: ‘We have enough steel, concrete and glass-towers in our cities.’ They add that their tower ‘tries to establish a direct connection to nature with plants and its natural materiality’.

Rendering of the Toronto Tree Tower by Studio Precht

People want to live in cities for the vibrancy, the rambunctiousness, at times the chaos, not to be drones under a sterile but efficient dome. The vision includes not more cameras, but automated irrigation systems, fruit-picking from public fruit trees, mobile planter boxes and public areas so people can interact.

Surveying the competing versions of the future on offer, it is easy to get dizzy. After all, part of the allure of solarpunk and other ecofuturist visions is that they offer an entwinement of humans and nature, and humans with humans, in partnership rather than domination. This sense of coming home, where the pain of separation is resolved, and where the excesses of the human psyche fall away in the loving embrace of nature’s wonder or the smile of a neighbour, and a rock-solid feeling of ‘enough’ encapsulates the sense of sufficiency that solarpunk provides.

In the marshlands of Iraq, entire villages are made from qasab reeds, and life rises and falls with the water

In its technological jiu-jitsu, solarpunk tries to flip the logic of industrialisation. It imagines a way of making things that work with living systems, instead of overriding them, turning production toward biophilic, cradle-to-cradle creation in sync with the rest of life. To do that, it embraces many technological traditions, in line with the thinking of the Hong Kong philosopher Yuk Hui’s cosmotechnics: the idea that every culture’s technical activity (technē) is grounded in a particular cosmology, its way of understanding and relating to the cosmos, nature and existence. As Western mechanical and digital technologies were globalised, they often eclipsed other ways of making and knowing; cosmotechnics pushes back against the idea of a single universal template, insisting that our technologies have always been multiple and diverse.

Such plurality is evident in the biomimicry Julia Watson documents around the world in her book Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism (2019). In Meghalaya, India, she describes the Khasi living root bridges, which are grown rather than built. In the marshlands of Iraq, she points to Ma’dan reed architecture, where entire villages are made from qasab reeds, and life rises and falls with the water level – an everyday symbiosis with flood and drought that adapts, and eventually decomposes, like the marsh itself. While solarpunk futures often stress the ‘gee-whiz’ factor of high tech integrated with nature, it is worth noticing that some of the most important technologies are the ones Western eyes failed to recognise as technologies precisely because they blend seamlessly into ecosystems. They may be exactly what we need to pass through the narrow neck of our current metacrisis.

HSBC Rain Vortex at Jewel Changi Airport, Singapore. Photo by Matteo Morando/Wikipedia

Honouring our emergence from and embeddedness in complex ecosystems removes the burden of coming up with all the technical solutions ourselves. Surrendering into what Buddhists call Pratītyasamutpāda, or interdependent co-arising, means cultivating our habitats by finding cultural practices that fit the situation; it also means that our technologies must hum to the tune of the ecologies around them, coming from renewable resources, and composting back into them. Making the best of our current tools is part of this great transition: taking a note from nature, we can morph them into longer-lasting, more robust, commons-oriented systems and, eventually, into biotechnics, or technologies that work with the organic order rather than against it.

If it takes smart contracts to decentralise governance, blockchains to support public accountability, and reinventing the materials our physical environment is made from, so that people get what they actually want without overshooting planetary limits, so be it. Solarpunk welcomes an integrated view of nature and technology, treating them as intertwined rather than opposed. It imagines a cosmotechnics that acknowledges culturally and environmentally bespoke ways of making, and a biotechnics that treats design as symbiosis rather than domination. It redefines the territory of technology and nature, asking how we can use our tools to serve the living world, rather than the other way around. It promises a world based on mutual aid and solidarity, smilingly acknowledging the self-sabotage of gratuitous competition and scarcity.

This attractive future of thriving in global peace and abundance prompts the question: who is tuning into the solarpunk frequency to advance its timeline? Some might resist, but solarpunk doesn’t ask us to deny what we’re losing. It asks us to notice what is already germinating in the cracks.