It might come as a surprise to learn that there was ‘any semblance of art’ in Nazi concentration camps, as Viktor E Frankl writes in Man’s Search For Meaning (1946). But there was. Frankl describes the improvised ‘cabaret’ that took place in his camp:

A hut was cleared temporarily, a few wooden benches were pushed or nailed together and a programme was drawn up. In the evening those who had fairly good positions in the camp – the Capos and the workers who did not have to leave camp on distant marches – assembled there. They came to have a few laughs or perhaps to cry a little; anyway, to forget. There were songs, poems, jokes, some with underlying satire regarding the camp. All were meant to help us forget, and they did help. The gatherings were so effective that a few ordinary prisoners went to see the cabaret in spite of their fatigue even though they missed their daily portion of food by going.

Perhaps more surprising still, Frankl highlights the importance of humour in the camps, explaining that it was ‘another of the soul’s weapons in the fight for self-preservation’.

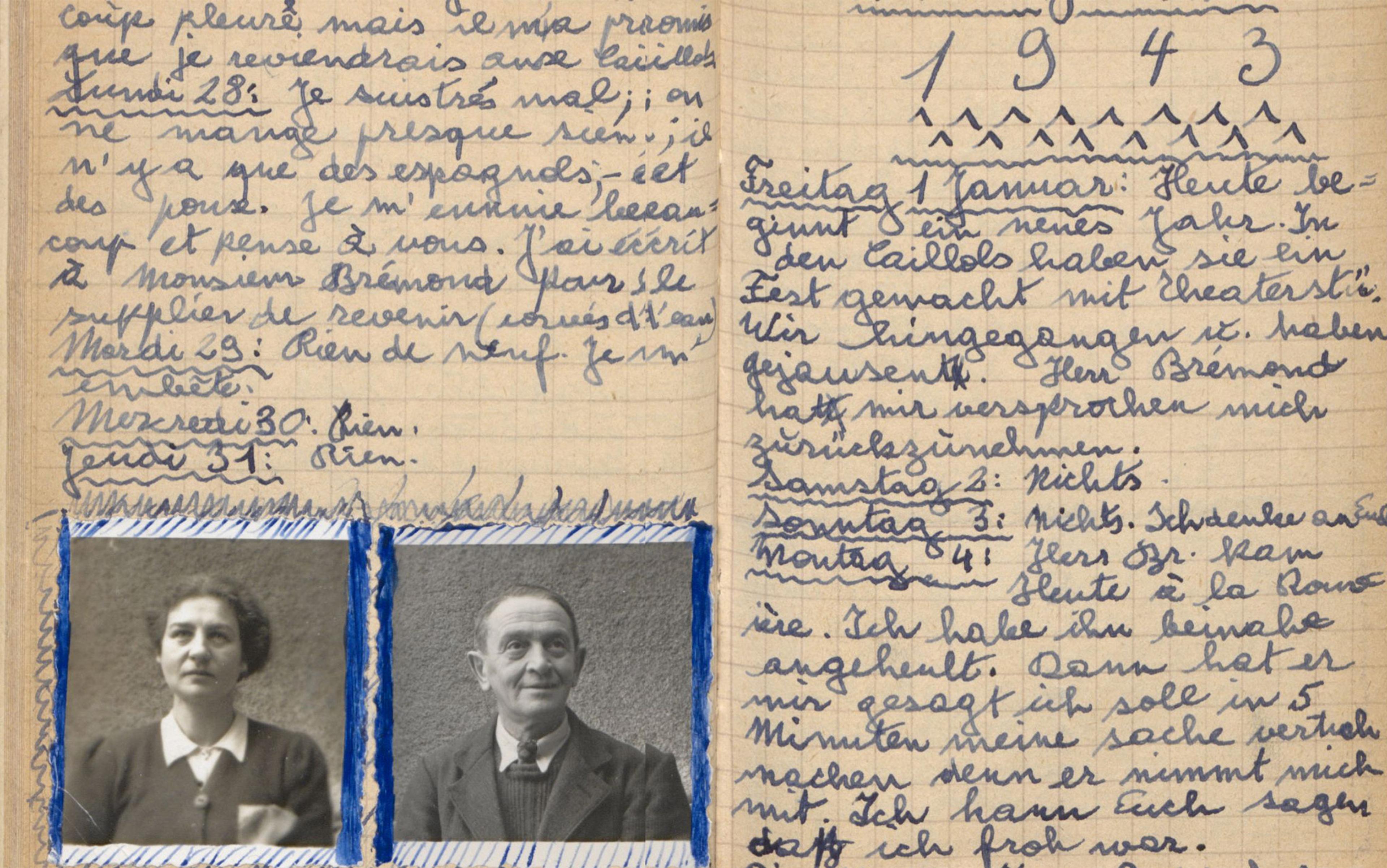

This year I have been reading a selection of autobiographical writings by Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. The six writers in question came from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and different countries across Europe. Three survived concentration camps. The significance of art, creativity and cultural life is a theme that emerges implicitly and explicitly across the various texts, and this prompted me to reflect on wider questions about the value of the arts and the humanities.

Like Frankl, Otto Dov Kulka writes of the ‘skits’ performed during his time at Auschwitz, and of the ‘special’ and ‘unique black humour’ that he developed there. Born in Czechoslovakia in 1933, as a child Kulka was sent to Theresienstadt and then to Auschwitz. In his Landscapes of the Metropolis of Death (2013), Kulka repeatedly mentions Herbert, a fellow inmate, who made a lifelong impression on him:

It was Herbert who gave me a copy of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Herbert who explained to me who Beethoven was, and Goethe, and Shakespeare, and about the culture they bequeathed us – that is, European humanism.

Kulka also recalls Fredy Hirsch, another camp inmate, who ‘devoted both himself and the team of madrichim [instructors] he chose to educating and looking after the youngsters’. Kulka remembers history lessons and artistic performances, including plays, concerts and a children’s opera. Hirsch’s barracks ‘became the centre of the spiritual and cultural life of the place’. For Kulka, the significance of these experiences was such that they ‘unquestionably form the moral basis for my approach to culture, to life, almost to everything, as it took shape within me during those few months, at the age of 10 and 11’.

Of course, as Kulka emphasises, there was a brutal limit to cultural and artistic escapism in ‘the Metropolis of Death’ – a place from which he and the other inmates expected never to return. The lessons and performances all took place ‘150 to 200 metres from the selection platform and 300 to 400 metres from the crematoria’. Similarly, Frankl underscores that ‘any pursuit of art in camp was somewhat grotesque’, set against the ‘background of desolate camp life’. Kulka puzzles over one ‘particularly bizarre’ artistic experience. He mentions Imre, who took on the role of children’s choir conductor in the camp. Kulka wonders how to interpret Imre’s choice to teach the children a song about ‘the brotherhood of man’, which Kulka later discovered was Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Another boy pointed out the ‘terrible absurdity’ and ‘terrible wonder’ of playing that song ‘opposite the crematoria of Auschwitz’. Was Imre expressing an undying commitment to those universal values, Kulka asks himself, or was this performance ‘an act of extreme sarcasm’?

Beethoven’s music also features poignantly in Elie Wiesel’s Night (1958). At 15 years old, Wiesel was transported from Sighet in Romania to Auschwitz. Wiesel’s is the most devastating of all the six accounts I studied, in part because he lost any sense of hope on his first day at Auschwitz. Having been separated from his mother and sisters, and then witnessing the unimaginable sight of small children ‘thrown into the flames’, he died a kind of death, too. His own soul was ‘invaded – and devoured – by a black flame’. Later, Wiesel was moved to Buna labour camp. As the Soviet army advanced on the Nazis, Wiesel describes how the SS ‘evacuated’ all prisoners from Buna and marched them further from the battlefront. They were forced to run for hours on end in the dark, through snow and ice. Those who couldn’t keep up were shot, trampled underfoot or froze to death.

On arrival in Gleiwitz camp, the prisoners were crowded into barracks where people were falling on top of one another and getting crushed. Wiesel recognised the voice of Juliek, a Jewish violinist from Warsaw who had played in the Buna orchestra. That night, ‘in a dark barrack where the dead were piled on top of the living’, Wiesel heard Juliek playing part of a Beethoven concerto on his violin. ‘Never before,’ writes Wiesel, ‘had I heard such a beautiful sound.’ This also represents a final act of rebellion, for earlier in the book we learned that Jewish musicians in Buna were not allowed to play German music:

The darkness enveloped us. All I could hear was the violin, and it was as if Juliek’s soul had become his bow. He was playing his life. His whole being was gliding over the strings. His unfulfilled hope. His charred past, his extinguished future. He played that which he would never play again.

Juliek died that night.

We also encounter Beethoven in Sarah Kofman’s memoir Rue Ordener, Rue Labat (1994). Kofman and her mother were taken into hiding in Paris by a French woman whom, at the lady’s request, Kofman called Mémé. Kofman remembers that she and Mémé would ‘listen to “great music” all the time’ and that Mémé introduced her to ‘Beethoven – her passion’. As well as enduring the trauma of being separated from the rest of her family – her father, a rabbi, was seized from his home in 1942 and Kofman never saw him again – she alludes to the guilt and confusion she felt as Mémé came to displace her own mother in her affections. She discusses the bitter custody battles fought between her mother and Mémé after the war. Kofman recalls the books that were her companions throughout this period, including Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a collection of Charles Dickens’s works, and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Roads to Freedom (1945-49). She also writes movingly about Madame Fagnard, a much-loved teacher from her life before going into hiding:

Whenever the siren sounded, we would go down into the cellar of the Lemire bookstore with her. She made us forget about the air raid and our fright by having us sing or play games or by telling us stories like the rather disturbing Pied Piper of Hamelin to distract our attention from the immediate danger. She gave piano lessons in her home. Knowing my family’s poverty, she didn’t make me pay for the lessons. She would come to the house bringing us toys, stories from the Bicot series, and other books. I remember getting a little doll from her … housed with its clothes in a small brown artificial snakeskin trunk. To my utter despair, I was never able to get it back after our apartment was sealed off by the police.

The title of Judith Kerr’s autobiographical novel, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (1971), also refers to a cherished childhood toy, from which the protagonist was separated when her family fled Berlin. In the novel, the children Anna and Max – refugees from Nazi Germany – crave the normality of going to school, making friends and playing with other children.

Those who were children in hiding highlight the importance of play

In Behind the Secret Window: A Memoir of a Hidden Childhood During World War Two (1993), Nelly S Toll recounts a (doomed) escape attempt, where she and her mother joined a group trying to cross the border from Poland into Hungary. After a long period of hiding in a barn in a forest, Toll and two friends were eventually permitted to go outside. They were ‘ecstatic’ at being able to play, to sing, to watch the clouds and the birds – to be children. During their precarious existence in the Lwόw ghetto, after her younger brother, aunt and cousin had been rounded up by the Gestapo and Ukrainian police, Toll notes that her parents, ‘like many other adults in the ghetto’, still tried to ‘provide educational and cultural experiences for their children’. When she and her mother went into hiding in a small room in an apartment, a neighbour in the block bought her some paints. Painting offered her a kind of sanctuary:

Once I started to paint, a new world opened up for me. It was as if the little box of watercolours made a bright path straight through the apartment walls to the outdoors … In my pictures there was no war, no danger, no police, and no tears.

The neighbour also brought Toll books from the library. Toll remembers reading Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Goethe and Dumas, among others, as well as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). She loved learning about Greek mythology and history with her mother.

In all these individual accounts of suffering and survival, we come across at least some mention of art, learning and cultural life. Most discuss music, literature, writing, education and creativity. Those who were children in hiding highlight the importance of play. I should add that Frankl was an academic, Kerr became a novelist and illustrator, Kofman a philosopher, Kulka a historian, Toll an artist and academic, and Wiesel a journalist and writer. In a sense, then, perhaps it seems less surprising that these subjects were salient for them – although, as Kulka points out, his history lessons in Auschwitz were themselves ‘formative’:

Sometimes I chuckle to myself when I consider the possibility that the encounter which perhaps destined me for the profession which as a young man, when I arrived at the university, I at first saw no point or purpose in pursuing – the study of history – had its roots in that formative experience. Possibly.

Nonetheless, that this theme emerges in all six of these diverse accounts is notable and worthy of exploration.

This phenomenon is also present in other contexts of dispossession and persecution. In a recent article about the movements of refugees, I mentioned a visit to ‘Call Me by My Name: Stories from Calais and Beyond’ (2017), at the Migration Museum in London. The exhibition focused on the experiences of refugees and other migrants in the Calais ‘Jungle’ camp. I emphasised the impression it conveyed that arts, creativity and cultural life were crucial features of the camp. The writer, journalist and academic Behrouz Boochani, who was incarcerated for years in Australia’s detention centre on Manus Island, has written about the importance of the arts for survival, expression, empowerment and protest in the Manus prison camp. Boochani quotes the detained musician Mostafa ‘Moz’ Azimitabar’s moving words about his art: ‘Music is a tool for preserving my sense of personhood, it is so I don’t forget that I am a human being.’

In No Friend but the Mountains (2018), Boochani describes some of his own experiences as a refugee fleeing Iran, and then as a prisoner in immigration detention. When he left Tehran, he carried nothing with him but the clothes he was wearing, some cigarettes and ‘a book of poetry’. Of his time in Manus, he explains that he had ‘reached a good understanding of this situation: the only people who can overcome and survive all the suffering inflicted by the prison are those who exercise creativity’. He mentions ‘the quiet singing of folk ballads’ that transported him back to Kurdistan, as well as the lively dance performances in the camp which represented, among other things, a ‘form of resistance’.

One reason why this particular theme stood out for me here and now, as we undergo a deep and destabilising global crisis, is that it appears to offer us a lesson about the fundamental importance of the arts, humanities and space for creativity in our lives. The lesson is drawn from the worst of contexts and experiences, but has wider resonance.

Yet in many places this message is ignored, and we are witnessing a failure to support these crucial subjects, practices and industries. They’re treated as expendable, as low down on the list of priorities. Indeed, in some cases we’re seeing active attempts to divert students and funds away from research and teaching in the arts and humanities in universities and schools. For example, the Australian government has announced plans to more than double the fees for humanities degrees. In the United Kingdom, the government has set up a ‘Higher Education Restructuring Regime in Response to COVID-19’. It states that ‘those providers’ needing support from the ‘Restructuring Regime’ will be required to ‘make changes that will enable them to make a strong contribution to the nation’s future’, for example:

[they] should ensure courses … focus more heavily upon subjects which deliver strong graduate employment outcomes in areas of economic and societal importance, such as STEM, nursing and teaching. Public funding for courses that do not deliver for students will be reassessed.

University research and education is seen as a means to the end of creating ‘job-ready graduates’, and as a ‘vital component’ of the economy.

Beyond education, the arts and cultural sector is facing its own emergency, with event cancellations, lack of revenue, mass job losses and venue closures. Although the UK government eventually promised a support package for the arts, the announcement came late (in July, when venues had already been closed for months, and with many practitioners out of work). In general, we get the impression that those in charge of national curricula and funding and ‘restructuring regimes’ don’t appreciate the value of the arts, humanities and creativity.

These pursuits matter to people as expressions of their humanity, tenacity, love and defiance

Practitioners, scholars and institutions in the arts and humanities are accustomed to this lack of government appreciation for the value of their work. We have also become familiar with a variety of attempts to defend these pursuits. Some operate within the terms of the dominant ‘economic value’ framework. They seek to show, for example, that universities are already ‘an engine of growth’, that the arts and humanities train students in useful ‘transferable’ skills, which make them highly employable, and that the creative industries make a significant contribution to the economy. We also hear that the arts and humanities are instrumental in fostering a robust democratic culture, as well as for the population’s mental and physical wellbeing. Some defences focus primarily on the noninstrumental value of pursuits in the arts and humanities – not (or not only) as a means to some other worthwhile end, but as ends in themselves.

However, another simple but powerful way of thinking about the value of these pursuits is to recognise and acknowledge that they are, in fact, valued. As we have seen, they matter to people, as sources of meaning and beauty, of hope and solace, of escape and liberation. They matter to people as expressions of their humanity, tenacity, love and defiance. In short, people actually do value them, and want them in their lives.

What’s more, they’re valued at moments of crisis, and they’re valued by people who have so much to teach us about what matters. Their experiences have afforded them a special kind of knowledge about humanity and inhumanity. As Boochani puts it, the refugees in Manus prison have changed their ‘understanding of life’ and this ‘needs to be considered in terms of epistemology’. The writers discussed here were persecuted, forced from their homes, separated from their loved ones, stripped of their possessions, their dignity, and in some cases their sense that they would live to see another day. Even in the most desperate of these accounts – Night – and in the darkest of places, Wiesel describes the dying Juliek’s rendition of Beethoven on the violin as the most beautiful sound he had ever heard. These insights from people who felt compelled to record their experiences – who, in the words of the French writer and concentration camp survivor Robert Antelme, ‘wished to speak, to be heard at last’ – carry a special kind of weight. ‘Only those who experienced Auschwitz know what it was,’ writes Wiesel. ‘Others will never know.’ The rest of us will never know, but we can and must listen.

Recall Frankl’s observation that some people were willing to forego their meagre ration of food and forget their fatigue to attend the artistic performances in the concentration camp. For me this is a potent reminder to challenge crude approaches to ranking basic human needs and the components of a decent human life. Of course, we need food and shelter in order to survive but, as Frankl points out, we also need reasons to live. Laughter, stories, play, dance, music: we learn that these, too, are basic needs and fundamental components of decent human lives.