For decades, went the story, books, candy and propane tanks had gone missing from a small community called Pine Tree on North Pond in central Maine. This was a place surrounded by wilderness; in the winter, it was a wilderness buried in snow. Its residents grew perplexed. Who among them would steal? The stories multiplied: it was a stranger, a phantom, a ghost… A hermit. He metamorphosed, over the years, into a legend. No one was sure if the hermit was real.

One night, while stealing food from a kitchen, he was caught out by a motion-detector linked to an alarm. There he was: the North Pond hermit. He was real. The police were called and, in April 2013, the hermit was arrested. Later, he was sent to jail.

This is where the outside world began to intrude, and the story’s borders began to blur. A few months after the arrest, GQ magazine sent the writer Michael Finkel to meet the hermit. A profile, titled ‘The Strange and Curious Tale of the Last True Hermit’, ensued. It seemed we were in for an adventure story, a real-life Hardy Boys: man rejects society, man is lured back into society and, in the end, we all learn a lesson about human nature and self-reliance.

But the story veered off-course. Despite heady preconceptions of Hemingway and Kipling and all the other great white male adventurers, the writer could see that the hermit’s tale was one of these man-conquers-wilderness stories only insofar as it included both a man and some woods. Instead, the Maine hermit’s story resembled something far older: a fairy tale. Young man walks into the woods, becomes spellbound, only to emerge years later, older, stranger and forever transformed.

This didn’t stop the writer from trying. Why did he do it? he asked the hermit. Surely, ‘There must have been some grand insight,’ something – enlightenment, tranquility, even a poem – ‘revealed to him in the wild.’ But what?

Nothing really, said the hermit. He simply wanted the freedom to be alone.

I thought about him often, the Maine hermit, after I read this profile, and I sat and wondered about the speed with which I was whirring through my own ordinary life. How, exactly, did he do it? The winters are cold in Maine, and his shelter was only a tent. Why did he do it? I too found it hard to take ‘no motivation’ for an answer. What, exactly, was it like, to be so alone?

I began to wonder if I had it in me. I lived in a city, after all; the whole endeavour seemed difficult, even suicidal. One night, I searched ‘woman alone in the woods’ online, just for kicks. The results were discouraging: a stock photo on the first page was named, tellingly: ‘Sad Lonely Woman Walking Alone Into the Woods’. A few other hits explained that women, if we’re sane, simply couldn’t go hiking alone; it wasn’t safe. We’re weak, and besides, there are bears – you don’t want to be mauled and eaten, do you?

I didn’t. But the results still bothered me. I was reminded of the medieval anchoress, of Virgil’s wandering sibyl; she who, ‘with raging mouth’, wrote Heraclitus, ‘utter[s] things solemn, rude, and unadorned’. I recognised in myself, too, a certain stirring that occurred whenever I was reminded of Henry David Thoreau’s axiom: ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately.’ But Thoreau was a part of the problem: Walden (1854), his journal of two years of solitude among nature, can’t even conceive of a woman alone.

Again and again, the most famous, the most celebrated, hermits and recluses are men: Thoreau, of course, but also Christopher McCandless who lived (and died) alone in Alaska, as portrayed in the film Into the Wild (2007); J D Salinger, a recluse after the success of The Catcher in the Rye (1951) until his death in 2010; the polar explorer Richard Byrd, author of the memoir Alone (1938); the American poet Thomas Merton who became a Trappist monk.

today, we don’t burn witches, we just shame them

Going back further: the ascetic Saint Jerome; Laozi, founder of Taoism; but also Muhammad, Jesus, Gautama Buddha. And Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Books on recluses are always quoting Rousseau: ‘Man is born pure, it is society that corrupts.’

And Rousseau’s plan for women? From Émile, or On Education (1762):

The women’s entire education should be planned in relation to men. To please men, to be useful to them, to win their love and respect, to raise them as children, care for them as adults… these are women’s duties in all ages and these are what they should be taught from childhood.

‘Sad Lonely Woman Walking Alone Into the Woods’: if the hermit is always a man, if there’s nobility in his solitude, then what’s left for women? Old maid. Hag. There must be something wrong with her. Don’t pretend that these aren’t still true; today, we don’t burn witches, we just shame them.

But for those of us who want to be alone, who still crave it even after all the abuse and skepticism, there are few guides and even fewer celebrations of female solitude. Who is the female hermit? Does she exist? Who is the woman who can look out at the world and in all seriousness say: ‘I want to be alone’?

To be alone, after all, is to admit to that rare quality: a contentment with one’s self.

The word ‘hermit’ comes from the Latin translation of the Greek word for ‘of the desert’, and the hermit’s history is almost as garbled as its linguistic origins. While ascetics crop up rather frequently in antiquity – the Greeks, through Alexander, were aware of the forest hermits of what is now Pakistan, and had their own Cynics, besides – ‘hermit’ as a term is used most often to denote the desert dwellers of the early Christian church and the religious orders that followed. Paul of Thebes, the first of these so-called ‘Desert Fathers’, fled to the Egyptian desert in the mid third century C.E. His only companion, supposedly, was a raven that visited him daily, clutching half a loaf of bread in its claws.

What would compel a person to do this, to run into the desert and wander, unabashed, until either her soul was scrubbed clean or she died? To love, sometimes, is to peel back the skin, and watch the bone bleach white beneath the sun.

‘I was like a fire of public debauch,’ Mary of Egypt told Zosimas of Palestine, the priest who found her wandering the desert 47 years after she first escaped. After Paul of Thebes, Saint Anthony popularised the hermit practice; scholars speculate that hermitdom, with its code of self-denial, spread as a replacement for martyrdom, no longer an option in the newly Christian Roman Empire. Christianity is built on sacrifice, and in this Mary of Egypt, the first female hermit, excelled.

Like Mary Magdalene before her, Mary entered her religious awakening a dissolute woman and emerged from it a saint. ‘And how can I tell you about the thoughts which urged me to fornication, how can I express them to you, Abba?’ she asked Zosimas. ‘A fire was kindled in my miserable heart… As soon as this craving came to me, I flung myself on the earth and watered it with my tears.’

At 17, the story goes, Mary began giving her body to passing pilgrims, not out of economic necessity but as a method of self-immolation. This is familiar territory; one of the many, now cliché, ways in which women are supposed to act out our pain: we hurt ourselves, while men hurt others. One-night stands, self-harm, our tenuous relationship with food: the question it most often comes down to is: how can we best escape our bodies? At 29, Mary attempted to enter a church, and found that she couldn’t cross its threshold. Something, be it God or some other mystery, barred her; she understood, in this moment, that she needed to get out. She needed to run. She needed to be free.

She went to the desert with only three loaves of bread, and this is where, 47 years later, Zosimas found her, transformed. Now she was an old woman of 76. In the desert, Mary told Zosimas, she battled wild animals and tore at wild herbs for food and baked beneath the endless sun. She would not admit to inner peace. ‘Why do you wish, Abba Zosimas,’ she asked him, ‘to see a sinful woman? What do you wish to hear or learn from me, you who have not shrunk from such struggles?’

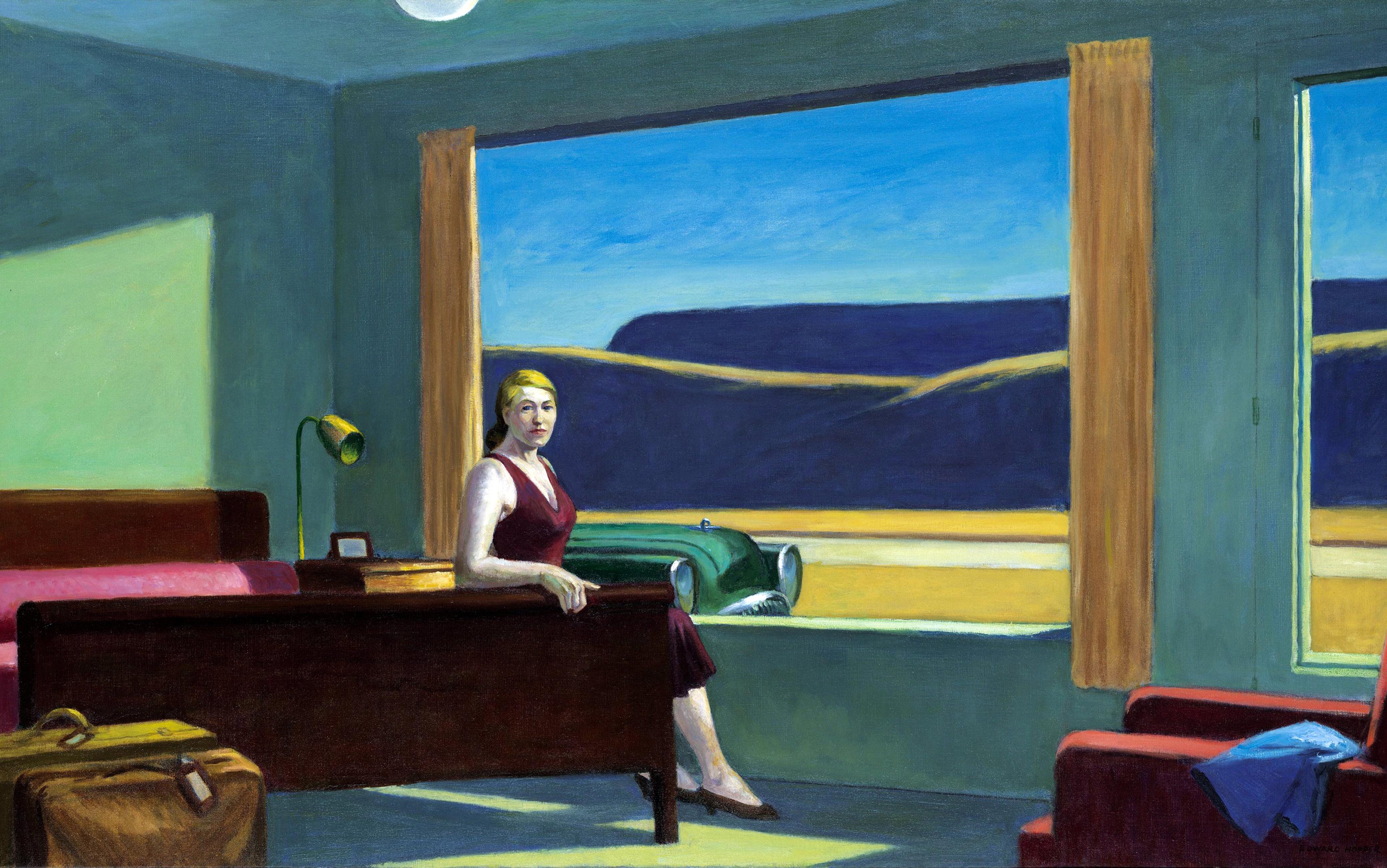

I bring up Mary not because I am trying to convert anyone, but because in her public struggle, I see an aspect of myself. Hers were the problems and self-hatreds that we women are still taught to torture ourselves with today: sex as a bartering chip, sex as a method of validation, of proving one’s credentials – credentials that, more often than not, men get to define. ‘Men look at women,’ the art historian John Berger wrote in his survey of European art, Ways of Seeing (1972). ‘Women watch themselves being looked at. …The surveyor of women in herself is male: the surveyed female.’ What did Mary see when she looked at her own reflection? Herself? Or someone else’s vision?

We’re lying to ourselves if we think that this is what freedom looks like.

To be alone, though, is not the same thing as loneliness. Is there anything lonelier, after all, than lying next to a person who doesn’t love you, and knowing that they never will? Sometimes, it’s healthy to tell the outside world to go to hell. Sometimes, for the sake of one’s integrity, one’s sanity, you need to say no. I will not, I am not, I won’t – but what won’t you do? Where is the line? To be alone, you need to know who exactly you are.

There is a reason why humans prefer groups of two or more: it’s easier. It’s easier to delegate tasks, to point to one person and say: You will find our food; to tell another: You will lead us along the way. In fairy tales, kings and hermits are always finding each other. An Italian fairy tale features a holy hermit (male, of course) who, after helping a youth win both a princess and a kingdom’s worth of gold, demands half of everything, princess included. When the youth draws his sword, moving to cut the princess apart, the hermit relents, happy to see that the young man ‘held his honour dearer than his wife’.

The princess is the prize. But Mary of Egypt was no princess. Alone, only one person makes the decisions. Food, shelter, water – they’re all one person’s responsibility. This is what true freedom looks like: if you fuck up, you’re dead. If you don’t, you survive. If you survive, congratulations: no one owns you.

To create anything, we need to have the freedom to lead, unimpeded, into the murkiness of our own minds

Mary survived. A medieval icon depicts the moment Zosimas found her: clothed, he offers her a robe, a cloak, anything to protect her from the cruelty of the elements, the cruelty of our eager eyes. Her arm is outstretched. She’ll take the robe, sure – but not quite yet. This is a pictorial representation of our bated breaths. In this moment, the halfway point between yes and no, Mary’s back is bent forward; like an animal, there’s power in the spine. Also like an animal: the gold fur that covers her body, the same gold as the halo that crowns her head. One corner of her mouth turns upward, approaching something that can’t exactly be called a smile. From something wild comes beauty; from solitude, contentment.

Mary did it. You could do it. Why haven’t you?

Because not all women can be alone.

Often, our supposed weaknesses are used against us. It’s too dangerous, we’re told if we want to travel. You’re not strong enough, we’re told if we express any desire to hike, to build, to boat, to dream. We’ll die if we go outside. Even the men who say that they like smart women, independent women, mean something different from how women define the words: when those men say smart, they mean: I have strong opinions and she agrees with them. Independent as in: she’ll choose to follow where I lead.

But to work, we need to be alone. To create anything, we need to have the freedom to lead, unimpeded, into the murkiness of our own minds. ‘To be female and to demand such things as a retreat from life and from loved ones,’ writes the poet Leslie A Miller in her essay ‘Alone in the Temple’ (1992), ‘is difficult and different. To assert the need for retreat when one is young, a wife… seems selfish, stubborn, even crazy.’

To voice this need is difficult. A thousand years after Mary of Egypt and half a world away, a woman named Ji Xian wanted to be a nun. This was the late Ming dynasty, and there was a precedent: early Buddhist nuns, writes Susan Murcott in First Buddhist Women (1991), were ‘a radical experiment’, consisting, in their earliest phase, of ‘“female wanderers” who could live in the forest alone’. The scholar Grace S Fong, writing in the journal Early Modern Women in 2007, elaborates: for a woman such as Ji Xian, a daughter of the elite, there were, ‘except for Buddhist or Daoist nuns’, a ‘distinct lack of models and contexts for female reclusion’. Noblemen had options: recluse-poets, who gave up their court lives in favour of a life spent composing stanzas, were a viable tradition. Ji Xian was a poet, too, but her work portrays poignantly the full extent in which her art was limited by her sex. ‘I desire to imitate the recluse at Deer Gate,’ she writes. ‘But being a wife, what can I do?’

What could she do? What can any of us do? It’s difficult to navigate the boundaries of one’s own life. ‘You tell people what you’re doing, and they say, “You’re crazy,”’ the Swiss hiker Sarah Marquis told the New York Times in 2014, after walking 10,000 miles across the world by herself. ‘It’s never: “Cool project, Sarah! Go for it.”’ The potential for catastrophe is implicit: what if we’re lost? The means of production. Even for those women who, unlike Ji Xian, were able to become recluses, their womanhood becomes a disadvantage. Orgyen Chökyi, a 17th century Tibetan Buddhist nun known in the West as the ‘Himalayan Hermitess’, wrote: ‘May I not be born again in a female body. …I could do without the misery of this female life. / How I lament this broken chest, this female body.’ Femininity, as it turns out, can be a barrier to enlightenment.

A woman needs money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction – but what could Ji Xian have produced if she could have just been given the opportunity to be alone? How many women are there, before and after Ji Xian, named and nameless, elite or otherwise, who couldn’t be alone? ‘My deep appreciation is for high mountains,’ goes another of Ji Xian’s poems. ‘Lofty feelings – in vain there are dreams. / I always lodge them amongst the white clouds.’

Don’t you dare forget her name.

But why would anyone want to be alone? Try it for a moment. Lock yourself in another room, one entirely without the presence of other people, other voices. Disconnect your internet, turn off your phone. Allow yourself, for just a few minutes, to let the poses fall away. The angles. Let your public persona, so exhausting to maintain, disappear.

Breathe. There is your throat. There is the fly, buzzing in the ceiling corner. There is, also, something else: the silence. A silent room has its own timbre, its own weight. Breathe again; keep breathing. Allow life, with its heaviness, its dust, to slip away, unimpeded.

This is the feeling, sadly rare, of no longer being watched. The psychotherapist Carl Jung, after seeing a photo of the Arctic explorer Augustine Courtauld, remarked that Courtauld’s was the face of a man ‘stripped of his persona, his public self stolen, leaving his true self naked before the world’. For women, this is doubly true: a woman’s life is one lived under surveillance, a system of inner and outer regulations even more restrictive than a man’s. Even a simple stroll down the sidewalk becomes an exercise in self-loathing. Suck in your stomach. Straighten your hem. (What if it rides up, exposing you?) Every shop window offers a glimpse of your own reflection. Adjust, adjust, adjust.

It’s enough to drive a woman crazy (and isn’t this what we’re always being accused of?). It’s enough to drive any woman to the woods. It was this, a life lived under the eyes of men, their needs and their demands, that led Sarah Bishop, the hermit of Connecticut’s West Mountain, to the cave she called home. The writer Samuel Goodrich wrote a poem about her in 1823; in 1856, he recalled her story:

Male hermits have been frequently heard of, but a woman hermit is a rare occurrence. Nevertheless, Ridgefield could boast one of these among its curiosities. Sarah Bishop was, at the period of my boyhood, a thin, ghostly old woman, bent and wrinkled, but still possessing a good deal of activity. She lived in a cave, formed by nature, in a mass of projecting rocks that overhung a deep valley or gorge in West Mountain.

Bishop’s hermitdom, he goes on to observe, could be traced back to the Revolutionary War, when she was a young woman. During the war, the story goes, her father’s house was burnt down by the passing British troops and she, as has happened to women since time immemorial, was raped by a soldier.

All we know of Bishop comes from Goodrich, the last in a long line of men who defined the course of her life for her. For his muse, Goodrich allots a few pretty stanzas, some paragraphs in the memoir devoted to his own long life; he calls her the ‘nun of the mountain’, a nice term for a woman whose body was violated in the name of her country’s freedom. If Bishop kept a diary, perhaps it would have gone like this: Don’t tread on me.

‘I felt that the creation of a rustic cabin would be the solution to my homelessness’

And perhaps Thoreau was thinking of Bishop, and the precedent she set, when he built his cabin in the woods of Walden Pond. Probably not. Walden is a work central to national self-mythologising; Americans’ image of ourselves as a nation of individuals. There are precious few equivalents for America’s women, and little evidence in our ability to survive alone. But Anne LaBastille’s Woodswoman series of memoirs, which recount the cabin that the late American author and ecologist built on the shores of a remote Adirondack lake in the 1960s, could be one of them.

Woodswoman (1976), published during the height of the feminist Second Wave, begins with a divorce. LaBastille, who married young and, worse yet, married her employer, is given a month to find a new home for herself; ‘I had no place to go,’ she writes. ‘My own family was either dead or scattered, leaving me with no relatives to turn to. …Intuitively now, I made my decision. I would build a log cabin in the Adirondack wilderness. I hoped that a withdrawal to the peace of nature might remedy my despair.’ Most importantly: ‘I felt that the creation of a rustic cabin would be the solution to my homelessness.’

LaBastille’s writing lacks the lyricism of Thoreau, but it has its own considerable charms. Her books – Woodswoman, Woodswoman II (1987), Woodswoman III (1997), and Woodswoman IIII (2004) – are practical guides in homesteading, giving the impression that, if she could do it, so could anyone. LaBastille grew up outside New York City; though a keen interest in the outdoors was a major part of her childhood, the occasional camping trip does not make a wilderness expert. She made mistakes and, during one winter described in the first volume, almost died. But she survived.

In her second volume, LaBastille builds another cabin, explicitly taking her inspiration from Walden for what she calls ‘Thoreau II’. Like Thoreau the first, she provides a list of expenses: the total spent on building the cabin and obtaining the necessary permits is $578.05 in today’s money. Thoreau, on the other hand, spent $742.64. For less than $1,000 today, and for less than one of history’s most revered recluses, LaBastille builds herself a private oasis, an escape route, a home.

LaBastille is not the only woman to do so. There are more: the English modern-day hermit Rachel Denton, profiled in The Guardian in 2009. The 13th century Mugai Nyodai, the first female Zen master in the world. Martha Frock, who lived in the 1940s in a shack in the middle of the Florida Everglades. Anastasia the Patrician, a sixth century lady-in-waiting to a Byzantine empress who founded a monastery in Egypt. Margaret Kirkby, a second-generation hermit in 14th century England. Suchitra Sen, the Greta Garbo of Indian cinema. Despina Achladioti, the Greek patriot known as the Lady of Ro, after the deserted island where she took refuge during the Second World War. The Christian mystic Julian of Norwich. Robyn Davidson who trekked across the deserts of west Australia by camels. Even the poet Dorothy Wordsworth, to an extent.

All women who wanted to be alone.

Single: The Art of Being Satisfied, Fulfilled, and Independent (2004). Choosing Me Before We (2009). Living Alone and Loving It: A Guide to Relishing the Solo Life (2002). Falling for Me: How I Hung Curtains, Learned to Cook, Traveled to Seville, and Fell in Love (2011). Singled Out: How Singles Are Stereotyped, Stigmatized, and Ignored, and Still Live Happily Ever After (2006). Today, single women can support a cottage industry of self-help books. But the single woman, unlike the hermit, isn’t really alone – she’s simply, momentarily or forever, without a man.

So why aren’t there more women really alone, women hermits? A hermit, of course, is not just single, not just alone, but alone in a particular way: free from the dizzying pressures and possibilities of public life. The hermit is truly free from acting as lord or master, proprietor or minister, soldier or citizen, serf or king. The hermit is free even from the simple expectations of being a neighbour.

For women, for most of history, it’s been mother or maiden, daughter or wife. The roles shuffle, their names and details changing, but all share one feature: which man does she care for, which man does she take care of? Woman as defined by man; woman as seen by man. How unappealing. With so few choices, it’s clear why we know of so few women hermits, and why solitude is viewed as male.

This was the hierarchy that Mary of Egypt scorched herself of in the desert; the hierarchy that Ji Xian wandered away from in the corners of her mind; the hierarchy that Anne LaBastille wrote a guide against. By some miracle, these women were, in one way or another, hermits. But their escape was rare.

A woman alone, unwatched, unchaperoned and without children is impossible for us to process. What does she do with her time? Burn the witch. She doesn’t exist. But what of those women who, against all odds, refuse these rules? We don’t remember them. So here, instead, a commemoration to those few who did: ‘I want to be alone.’ That famous phrase. Think of it as another option, one so recognisable that, in a single breath, it created an enigma. Garbo made it seem so easy. Years later, she would claim: ‘I only said, “I want to be let alone.” There is all the difference.’ But too late. The words were spoken. The myth was made.

We imagine her clearly: glamorous, intelligent, those eyebrows, that face. ‘Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side, and don’t be stingy, baby.’ An actress is defined by her audience; after a decade in Hollywood, she must have been tired of watching herself being watched. Instead, a refusal: no one got to look at her, and she disappeared, transformed into a modern fairy tale. A woman alone is either a mystery or an object of pity; you tell me which was Garbo.