Tiziano Gérard might be the greatest chef you’ve never heard of. He combines the skills and repertoire acquired in the kitchens of five-star hotels in Monte Carlo, Milan and Sardinia with the traditional cuisine of the Aosta Valley in northwest Italy, where he grew up and learned to cook. Alongside his version of regional classics, such as alpine cheese wrapped and baked with Speck, and rich minestra soup with spelt and barley, are original dishes such as zucchini with black rice ‘tabouleh’ and toasted risotto with muscatel wine, parmesan and rosemary. Hearty fare, but you will want to find your second stomach for his perfect tarte tatin or hazelnut parfait and flambéed strawberries with pistachio ice-cream. To cap it all, the menu is as varied as it is incredible, changing every day. You can eat at Gérard’s table every night of the week and never have the same dish twice.

You might suspect that I am suffering from a traveller’s romantic delusion – the sort of thing that leads one to take home a bottle of glorious local digestif only to find it mysteriously undrinkable in the familiar surrounds of home. The only secret ingredient in many far-flung meals is the strange alchemy of food, drink, time and place. Could Gérard’s cooking have been elevated by the fact that I tasted it in the alpine idyll of the Gran Paradiso National Park, after a hard day’s walking?

I don’t think so. It was my second trip to the region and, much as I loved the food I ate on my first trip, Gérard’s was clearly in a different league. What’s more, such delusions of greatness don’t generally persist when you’ve eaten at the same place six nights in a row.

The real reason why Gérard is a culinary unknown is that the only people who eat his food are the half-board lodgers who stay at Hotel Petit Dahu, a small place he runs in an unfashionable alpine village with Valentina, the mother of his two young children. As talented as he is, Gérard’s one-man operation will never be a Michelin-starred destination restaurant. That kind of excellence requires a staff-to-customer ratio approaching 1:1. Intensely refined and extraordinary it might be, but Gérard’s cooking occupies a gastronomic no-man’s land between the resource-heavy, prestige avant-garde and the solidly traditional rustic table of the good local cook.

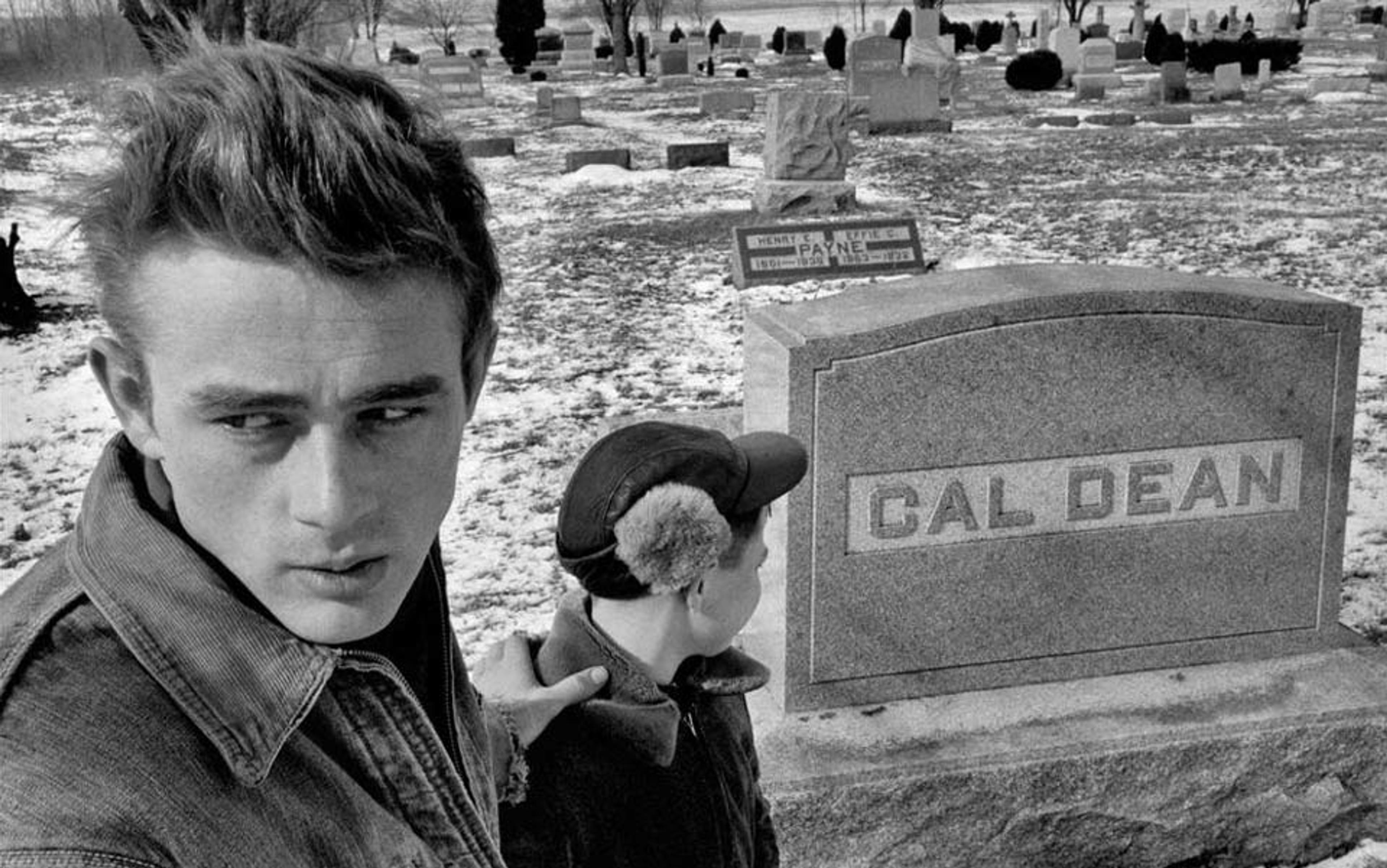

Tiziano Gérard. Photo courtesy the author

It is tempting to see Gérard’s obscurity as a kind of tragedy, or at least an injustice. But that would be a mistake. To my mind, Gérard embodies a very distinctive kind of success and ambition. To understand what that is, we need to enquire into the nature of recognition and fame in a world where those two things appear to be prized above all else.

In 2003, Joyce Meng, then a 16-year-old girl from Virginia, competed in the final of a national competition known as the ‘Kids Philosophy Slam’. For once, philosophy was not far removed from the interests and concerns of ordinary people but a perfect reflection of them. ‘Fame is a necessary component of self-fulfilment,’ she argued, ‘a pathway to the meaning of life.’ Given that history never remembers who comes second, I can only imagine how she felt when she was announced as the runner-up.

Perhaps she was just being provocative, but I remember feeling saddened that the brightest of youth could take philosophy and use it to derive such a wrong-headed conclusion. Yet it often takes a child to state plainly and unapologetically what the adult world implicitly believes. No right-thinking person would endorse what Meng said, but our behaviour suggests many of us agree with her in practice, if not in principle. An academic friend told me recently about a talk he gave, which was chaired by Richard Dawkins. The room was packed, but they were not there to hear my friend’s arguments. As soon as his talk ended, the hordes descended on Dawkins, ignoring the ostensible main attraction. Stardust is as potent a force in academe as it is anywhere else, whatever haughty dismissal of TV talent and reality shows you might hear around the coffee machine.

Fame is relative, of course. Most of us can honestly say we have no desire to be on the cover of Hello! magazine, yet almost all of us crave recognition, believing that it validates our endeavours. A myth of our age is that talent, dedication and ambition bring such recognition – and its associated rewards – in gastronomy as in everything else. Gérard is living proof that this just isn’t true. And, of course, he is not alone. The chefs we hear about are almost all of two kinds: either they run top-ranked, cutting-edge restaurants, or they serve the very best examples of traditional regional cuisines in simpler tavernas, osterias and brasseries. But there must be hundreds of truly excellent cooks who choose to work in other settings where you can’t even book a table, places that will never feature in restaurant guides.

The great philosophers would not have lamented this. The Stoics were entirely dismissive of the pursuit of fame, which they thought involved an excessive desire to please others. By example, Epictetus asks why we should feel annoyed when we ‘were not invited to some one’s entertainment’ – for our purposes, let’s call it an invitation to be a keynote speaker at a conference or to appear as a guest on a chat show. Everything has a price, says Epictetus, and the price of such invitations is that you must lavish praise and attention on those who can help you get one. Now it’s true that some individuals achieve fame without ever having sought it. But it’s far more likely that the desire for acclaim has driven them to ingratiate themselves with influential people in their field. In the restaurant world, for example, many of the most ambitious chefs are obsessed with winning Michelin stars and do all they can to satisfy the guide’s inspectors, even though they usually do not entirely agree with these judge’s verdicts. ‘Who are these people, by whom you wish to be admired?’ asks Epictetus. ‘Are they not the very people whom you have been in the habit of describing as mad?’

There is a fine line between the admirably self-contained and modest shokunin who doesn’t seek the approval of others, and the deluded egotist

Aurelius does, however, concede one benefit to recognition. ‘What use is praise,’ he wrote, ‘except to make your lifestyle a little more comfortable?’ Clearly he did not think this a significant gain, given the concomitant losses. Aristotle’s view was more moderate. He believed it was good to be able to accept an appropriate degree of recognition with good grace for deeds that merit it. But he insisted that honour could not be the highest good because it ‘is felt to depend more on those who confer than on him who receives it’. Our focus should be on cultivating virtue and excellence, not the good reputation that often comes with it.

The message is clear: you should do what you do to the best of your ability, and whether you gain recognition for it or not is secondary. This is the ethic of the Japanese shokunin, the true craftsman. These masters are completely dedicated to perfecting their craft, whether it is cookery or calligraphy, woodwork or weaving. Honour comes simply from the work, not from the recognition others give you for your doing it. Often this does indeed result in recognition. Japanese chefs who work as shokunin have become world-famous for the quality of their cooking, and Tokyo is home to more Michelin-starred restaurants than any other city in the world. But it would be wrong to conclude that focusing on your craft is just an indirect means to pursue the goal of fame. Perfecting one’s craft is all that matters: any recognition that comes along is a mere side effect.

Gérard confines his talent to a small stage because it enables him to pursue what matters most to him: his own ideal of culinary excellence. His ideal way of working is just himself, hands-on in the kitchen. He has tried other things. He once ran the restaurant next to the hotel, but he was too vexed by employees who did not share his ideals and were, as he told me, ‘afraid of hard work’. As for trying to create a high-end, Michelin star-seeking restaurant, Gérard would need to cook the kind of tiny, expensive dishes that he doesn’t like making, and it would entail leading a team, not doing all the cooking himself. He is a man so committed to his kitchen that he will almost certainly never achieve recognition outside it.

That’s really the key. A top chef plays a role that is entirely different from being a talented cook. A chef in a large restaurant is a creative director who has other people do most things. Gérard does everything himself. So if you want to enjoy the kind of personalised meal that comes from the hands of one cook, you will never find it in a restaurant with more than a dozen tables, or one that produces the kind of highly complicated food that needs a team of sous-chefs, chefs de partie, commis chefs et al to be prepared.

Peiti Dahu Hotel. Photo courtesy the author

Ideally, Gérard would have a small restaurant of five or six tables, and that is, in effect, what their homely dining room turns into each night. For a while, he and Valentina ran it as a restaurant, open to the public as well as the hotel guests, and they established something of a reputation, including the approval of the Slow Food movement’s prestigious Osterie & Locande D’Italia guide. But it wasn’t practical, as it created too much noise for the hotel guests and left little time to spend with his young family. So Gérard continues to produce his wonderful four-course menus each night for the few lucky guests who stay at his hotel.

Gérard’s lack of acclaim compared with his conventionally ambitious peers is not due to a lack of ambition: indeed the opposite is true. It is precisely his uncompromising ambition to be as good a cook as he can, and his success in fulfilling it, that prevents him from chasing wider recognition. In a deep sense, such quiet, modest men and women of the kitchen as him are the most ambitious of all, for their only concern is to cook the best meal possible each and every day. Isn’t that, rather than award and accolades, what a great cook should strive for?

Isn’t it what we should all strive for? It sounds simple: the only ambition worth holding is to do whatever it is that you want to do as best you can; the only true measure of success is whether you manage to do that. But the austerity and purity of this vision of the good life comes up against a problem. It seems impossible to judge our own success without some external measure. And this is not entirely mistaken. There is a fine line between the admirably self-contained and modest shokunin who doesn’t seek the approval of others and the deluded egotist who believes they have achieved excellence without any evidence that they have.

That’s why ultimately I side with Aristotle against the Stoics. Success does not require recognition, but it is better on the whole that people hear your music, read your words, taste your food, than not. Moreover, though we should not place too much emphasis on the opinions of others, to have no regard for them whatsoever is supremely arrogant. Recognition is a kind of success, even though it is not the ultimate measure of it.

The problem is that we often look for praise from the wrong people. The TV sitcom Father Ted (1995-98) captured this perfectly. The eponymous Irish priest yearns to be famous, because then people listen to what you have to say. His colleague Dougal points out that every Sunday his parishioners listen to his sermons. ‘No, Dougal,’ Ted replies. ‘I mean people I respect.’ For Ted, validation counts only when it comes from the wider world.

But as recognition widens, it can also become very shallow. What should matter is the deeper appreciation that comes from people who know you and your work more intimately. For the chef, the greatest satisfaction should come from seeing the delight of diners at your table, not the accolades from inspectors passing through or television audiences that have never even eaten your food. When recognition steps over the threshold into fame, it often becomes so thin because it ultimately ends up being sustained by itself. Recognition breeds recognition so, in the end, even those who are initially recognised for real achievements end up being famous mainly for being famous.

How fêted we are is a shallow measure of success that skips over the quality of our achievements and goes directly to the noise they create

Surveys repeatedly show children aspiring to be famous more than anything else, and many feel worried by this. But perhaps we should have more faith that, as they mature, they will be just as capable of recognising the emptiness of celebrity as the rest of us. The precocious Joyce Meng is case in point. Now nearly 30, she works in international trade and development and has founded Givology, ‘a 100 per cent volunteer-run social enterprise’ that connects donors to grassroots education projects and student scholarships around the world.

Meng learned that ambition and success need to be carefully separated from fame and recognition, which she and many others mistakenly lump together. It is more ambitious to pursue excellence, originality or the purity of your own vision than it is to chase sales, money or recognition. How fêted or popular we are is a shallow measure of success that skips over the quality of our achievements and goes directly to the noise they create.

We don’t need to repudiate fame or recognition altogether. On the contrary, it is good to enjoy praise when it is earned, as long as we do not make it the measure of value. If Meng’s work brings her recognition or perhaps even a kind of fame, it will be all the sweeter for having sprung from work that really matters to her. The trick is to know what you really want to do well, and make sure you are not being drawn away from it by the allure of the warm glow of praise. The validation of others is worth nothing if not conferred for that which we truly value ourselves.