One day in the early 1980s, I was flipping through the TV channels, when I stopped at a news report. The announcer was grey-haired. His tone was urgent. His pronouncement was dire: between the war in the Middle East, famine in Africa, AIDS in the cities, and communists in Afghanistan, it was clear that the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse were upon us. The end had come.

We were Methodists and I’d never heard this sort of prediction. But to my grade-school mind, the evidence seemed ironclad, the case closed. I looked out the window and could hear the drumming of hoof beats.

Life went on, however, and those particular horsemen went out to pasture. In time, others broke loose, only to slow their stride as well. Sometimes, the end seemed near. Others it would recede. But over the years, I began to see it wasn’t the end that was close. It was our dread of it. The apocalypse wasn’t coming: it was always with us. It arrived in a stampede of our fears, be they nuclear or biological, religious or technological.

In the years since, I watched this drama play out again and again, both in closed communities such as Waco and Heaven’s Gate, and in the larger world with our panics over SARS, swine flu, and Y2K. In the past, these fears made for some of our most popular fiction. The alien invasions in H G Wells’s War of the Worlds (1898); the nuclear winter in Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957); God’s wrath in the Left Behind series of books, films and games. In most versions, the world ended because of us, but these were horrors that could be stopped, problems that could be solved.

But today something is different. Something has changed. Judging from its modern incarnation in fiction, a new kind of apocalypse is upon us, one that is both more compelling and more terrifying. Today our fears are broader, deeper, woven more tightly into our daily lives, which makes it feel like the seeds of our destruction are all around us. We are more afraid, but less able to point to a single source for our fear. At the root is the realisation that we are part of something beyond our control.

I noticed this change recently when I found myself reading almost nothing but post-apocalyptic fiction, of which there has been an unprecedented outpouring. I couldn’t seem to get enough. I tore through one after another, from the tenderness and brutality of Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars (2013) to the lonely wandering of Emily St John Mandel’s survivors in Station Eleven (2014), to the magical horrors of Benjamin Percy’s The Dead Lands (2015). There were the remnants of humanity trapped in the giant silos of Hugh Howey’s Wool (2013), the bizarre biotech of Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl (2009), the desolate realism of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006).

I read these books like my life depended on it. It was impossible to look away from the ruins of our civilisation. There seemed to be no end to them, with nearly every possible depth being plumbed, from Tom Perrotta’s The Leftovers (2011), about the people not taken by the rapture, to Nick Holdstock’s The Casualties (2015), about people’s lives just before the apocalypse. The young-adult aisle was filled with similar books, such as Veronica Roth’s Divergent (2011), James Dashner’s The Maze Runner (2009) and Michael Perry’s The Scavengers (2014). Movie screens were alight with the apocalyptic visions of Snowpiercer (2013), Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), The Hunger Games (2012-15), Z for Zachariah (2015). There was also apocalyptic poetry in Sara Eliza Johnson’s Bone Map (2014), apocalyptic essays in Joni Tevis’s The World Is on Fire (2015), apocalyptic non-fiction in Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us (2007). Even the academy was on board with dense parsings, such as Eugene Thacker’s In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy (2010) and Samuel Scheffler’s Death and the Afterlife (2013).

I would stand on the overpass and watch the cars flow underneath. They never slowed. There was never a time when the road was empty

In the annals of eschatology, we are living in a golden age. The end of the world is on everyone’s mind. Why now? In the recent past we were arguably much closer to the end – just a few nuclear buttons had to be pushed.

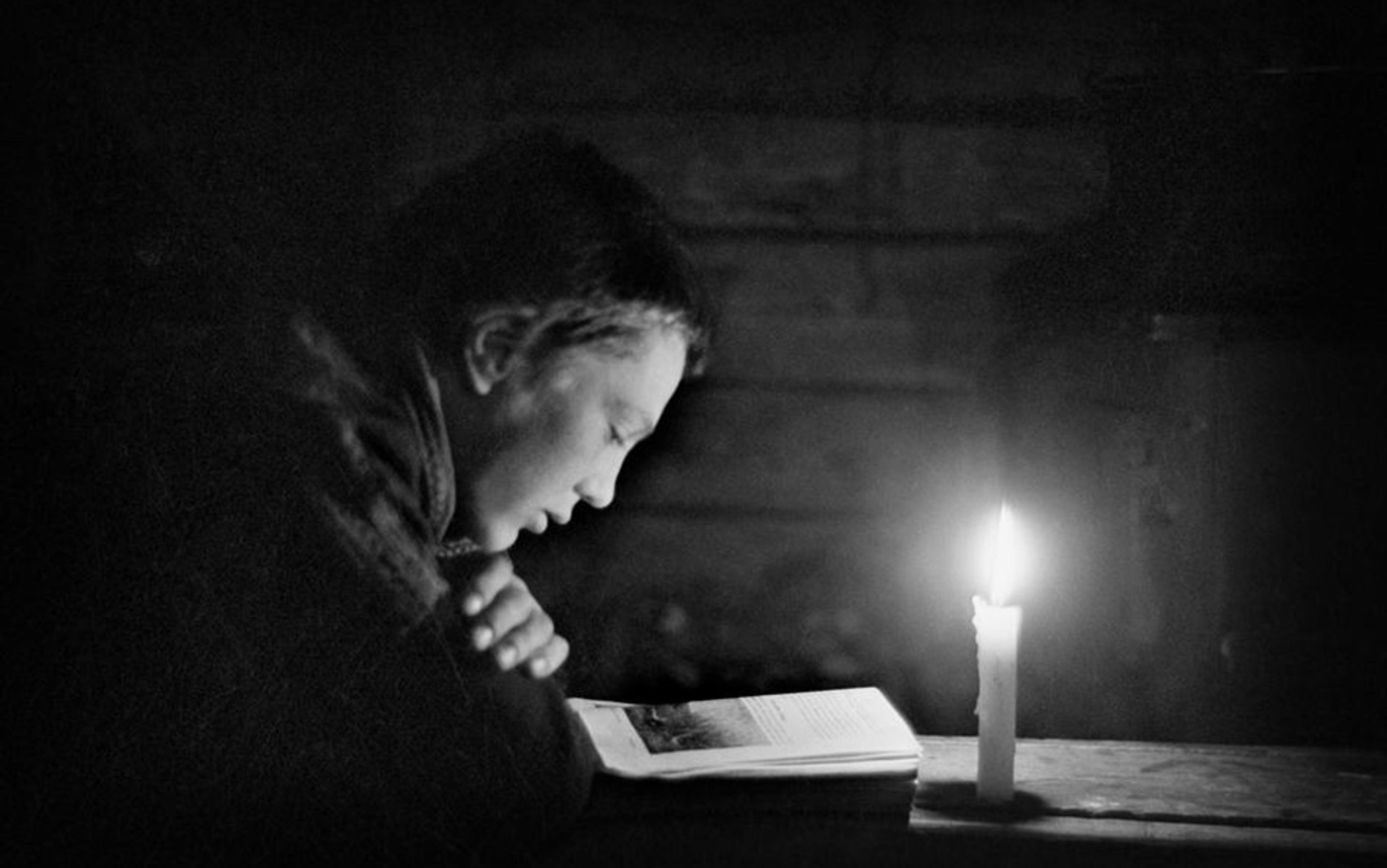

The current wave of anxiety might be obvious on the surface, but it runs much deeper. It’s a feeling I’ve had for a long time, and one that has been building over the years. The first time I remember it was when I lived in a house next to a 12-lane freeway. Sometimes I would stand on the overpass and watch the cars flow underneath. They never slowed. They never stopped. There was never a time when the road was empty, when there were no cars driving on it.

When I tried to wrap my mind around this endlessness, it filled me with a kind of panic. It felt like something was careening out of control. But they were just cars. I drove one myself every day. It made no sense. It was like there was something my mind was trying reach around, but couldn’t.

This same ungraspable feeling has hit me at odd times since: on a train across Hong Kong’s New Territories through the endless apartment towers. In an airplane rising over the Midwest, watching the millions of small houses and yards merge into a city, a state, a country. Seeing dumpster after dumpster being carried off from a construction site to a pile growing somewhere.

When I began my apocalyptic binge, I could channel that same feeling and let it run all the way through. It echoed through those stories, through the dead landscapes. And now after reading so many, I believe I am starting to understand the nature of this new fear.

Humans have always been an organised species. We have always functioned as a group, as something larger than ourselves. But in the recent past, the scale of that organisation has grown so much, the pace of that growth is so fast, the connective tissue between us so dense, that there has been a shift of some kind. Namely, we have become so powerful that some scientists argue we have entered a new era, the Anthropocene, in which humans are a geological force. That feeling, that panic, comes from those moments when this fact is unavoidable. It comes from being unable to not see what we’ve become – a planet-changing superorganism. It is from the realisation that I am part of it.

apocalyptic fictions of the current wave feed off precisely this fear: the feeling that we are part of something over which we have no control

Most days, I don’t feel like I’m part of anything with much power to create and destroy. Day to day, my own life feels chaotic and hard, trying to collect money I’m owed, or get my car fixed, or pay for health insurance, or feed my kids. Most of the time, making it through the day feels like a victory, not like I’m playing any part in a larger drama, or that the errands I’m running, the things I’m buying, the electricity I’m wasting could be bringing about our doom.

Yet apocalyptic fictions of the current wave feed off precisely this fear: the feeling that we are part of something over which we have no control, of which we have no real choice but to keep being part. The bigger it grows, the more we rely on it, the deeper the anxiety becomes. It is the curse of being a self-aware piece of a larger puzzle, of an emergent consciousness in a larger emergent system. It is as hard to fathom as the colony is to the ant.

Emergence, or the way that complex systems come from simple parts, is a well-known phenomenon in science and nature. It is how everything from slime moulds to cities to our sense of self arises. It is how bees become a hive, how cells become an organism, how a brain becomes a mind. And it is how humans become humanity.

But what’s less well-known is that there are two ways of interpreting emergence. The first is known as weak emergence, which is more intuitive. In this view you should be able to trace the lines of causation from the bottom of a system all the way to the top. In looking at an ant, you should detect the making of the colony. In examining brain cells, you should find the self. In this view, the neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga explains in his book Who’s In Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain (2011), ‘the emergent property is reducible to its individual components’.

But another view is called strong emergence, in which the new system takes on qualities the parts don’t have. In strong emergence, the new system undergoes what Gazzaniga called a ‘phase shift’, not unlike the way that water changes to ice. They are made of the same stuff, but behave according to different rules. The emergent system might not be more than the sum of its parts, but it is different from them.

Strong emergence has been grudgingly accepted in physics, a field where quantum mechanics and general relativity have never been reconciled, and where they might never do so because of a phase shift: physics at our level emerges from below, but changes once it does. Quantum mechanics and general relativity operate at different levels of organisation. They work according to different rules.

Whenever I think about reconciling my own life with that of my species, I have a similar feeling. My life depends on technologies I don’t understand, signals I can’t see, systems I can’t perceive. I don’t understand how any of it works, how I could change it, or how it can last. Its feels like peering across some chasm, like I am part of something I cannot quite grasp, like there has been a phase shift from humans struggling to survive to humanity struggling to survive our success.

The problems we face will not be fixed at the level of the individual life. We all know this because none of us have changed our own lives anywhere near enough to make a difference. Where would we start? With our commute? With candles? Life is already hard. Solutions will need to be implemented at a higher level of organisation. We fear this. We know it, but we have no idea what those solutions might look like. Hence the creeping sense of doom.

‘It doesn’t make sense,’ says a character in Mandel’s Station Eleven. ‘Are we supposed to believe that civilisation has just come to an end?’

Another responds: ‘Well, it was always a little fragile, wouldn’t you say?’

This is what our fiction is telling us. This is what makes it so mesmerising, so satisfying. In our stories of the post-apocalypse, the dilemma is resolved, the fragility laid bare. In these, humans are both villain and hero, disease and cure. Our doom is our salvation. In our books at least, humanity’s destruction is also its redemption.

Standing on that bridge now, I see even more cars than ever before. Beneath the roar of engines is the sound of hoof beats. As they draw closer, the old feeling rises up, but I know now that it comes not just from a fear of the end itself, but from the fear of knowing that the rider is me.