It was a moonlit night in early summer, about a year on from the great tsunami. As waves broke gently on a beach half-obscured in fog, Fukuji could just about make out two people walking along: a woman and a man.

Fukuji frowned. The woman was definitely his wife.

He called out her name. She turned, and smiled. Fukuji now saw who the man was, too. He had been in love with Fukuji’s wife before Fukuji had married her. Both had died in the tsunami.

Fukuji’s wife called to him, over her shoulder: ‘I am married now, to this man.’

‘But don’t you love your children?’ Fukuji cried out in reply. His wife paused at that, and began to sob.

Fukuji looked sadly at his feet for a moment, not knowing what more to say. When he looked up, the woman and the man had drifted away.

From Tōno Monogatari or Legends of Tōno (1910) by Kunio Yanagita, author’s translation

This is a true story. Or so the man who wrote it down wanted his readers to believe. Kunio Yanagita was one of Japan’s first folklorists. He collected such tales from the village of Tōno in Japan’s northeastern Tōhoku region, publishing them as the Legends of Tōno in 1910. His hope was to rekindle in the inhabitants of big, modern cities such as Tokyo and Osaka the feel of nature’s mystery and magic – the unknowns of the world – which, Yanagita worried, these people had of late begun to lose, mislaying it amid the noise and smog and reassuring distractions of urban life.

One hundred and one years later, stories much like Fukuji’s were told across Japan. A massive earthquake on 11 March 2011 sent a towering wall of putrid water surging inland from the Tōhoku coast. Television footage filmed from helicopters revealed familiar points of reference suddenly replaced by vast muddy lakes, as the fabric of everyday life – homes, offices, bridges, vehicles – was broken up and sucked out to sea, or else scattered across a new, barely recognisable landscape. People struggled to reach loved ones, first by phone and later by searching through the debris left behind as the waters receded. Some went on looking for weeks, months, even years, as the toll of the dead and missing rose towards 20,000.

Survivors of the disaster soon began seeing and feeling ghostly presences. Men and women dressed in warm clothes at the height of summer, hailing taxis and then disappearing from the back seat. A toy truck, belonging to a young boy killed in the tsunami, pushing itself haltingly around the room. One woman answered her door to a sopping wet stranger, who asked for a change of clothes. She went off to find something. When she came back, a whole host of people were standing there, all of them soaked to the skin.

Here was a new Legends of Tōno in the making. But why would Japan, a country so often associated with a secular, high-tech modernity – the fulfilment of much of what Yanagita had feared – find itself home to all this? Where do Japan’s ghosts come from? And what message do they bring?

Japanese awareness of ghosts – yūrei – goes back centuries, rooted in ideas of justice and injustice, and in a fear of unfinished business. If a person’s spirit is looked after at death, by a family providing a proper funeral, praying for that person, and visiting the grave, then the deceased is able to pass peacefully into the next world. From there, the dead look out for their still-living relatives, providing help and protection. Every year, in summer, they return to this world, welcomed by their families at the festival of Obon with food and drink, fireworks and dancing.

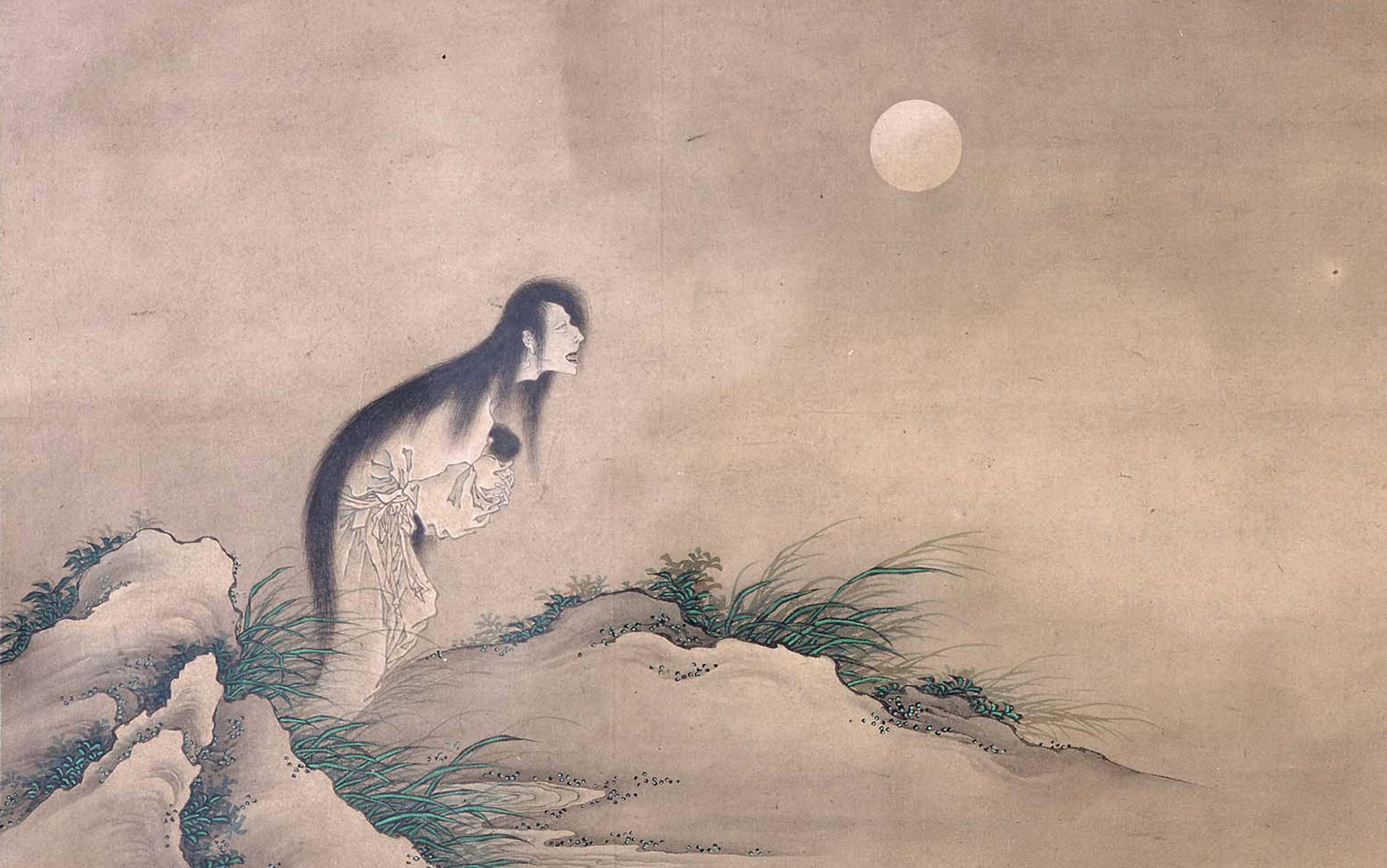

People who die suddenly, violently, wronged or alone are another matter. Their unpacified spirits might return to the world of the living in search of satisfaction. The spirits of women in particular have long been a prominent feature in Japanese stories, paintings, woodblock prints and kabuki plays: depicted with gaunt demeanours, empty eyes and long, tangled hair falling over their faces and down onto a white Buddhist burial shroud.

Some of the best-known of these ghosts are ubume: women who have died in childbirth. One classic tale has a woman wordlessly buying sweets in a shop, dropping a dried-up leaf into the payment jar. Perplexed, the shopkeeper follows her home – to a graveyard, where she disappears over a patch of earth. The sound of crying can be heard underneath. Digging up the soil, the body of the woman is found, clasping a living baby for whom she has been seeking out sustenance. And a famous work of Japanese literature, The Tale of Genji (c1000 CE), features another sort of ghost altogether: an ikiryō, a living or wandering spirit, propelled by anger and jealousy from the body of a living person to torment and wreak bloody vengeance on enemies.

The dead were being called upon to pacify the spirits of the living, rescuing them from life’s uncertainties

The message in sightings and stories alike was often a moral one. Vivid, compelling accounts of wrongdoing and its consequences served to circulate the essentials of Buddhist teaching among people lacking a formal philosophical education but who possessed a keen appreciation of human frailty along with an appetite for entertainment. But by the time that Fukuji’s tale was re-told by Yanagita for early 20th-century urbanites, this was starting to change: Japanese ghost stories had begun to reflect the disorientation that comes with rapid change.

Yanagita, for his part, was at pains to point out at the beginning of his Legends that he had recorded stories such as Fukuji’s exactly as he had ‘felt’ them. This, he hoped, would be a means of preserving and transmitting around Japan something of the way that the people of Tōno experienced life: as yet untouched, or untainted, by gakusha kusai koto, or things that ‘stink of the [modern] scholar’. By this he meant a recent and growing fascination with the problem-solving potential of technocratic objectivity – found most clearly in science and engineering – in the face of which other human ways of knowing and interacting with the world, from intuition to imagination to wonder, were in danger of withering away.

Japan’s sense of the supernatural seemed to be shifting: from the living working to pacify the spirits of the dead, to the dead being called upon to pacify the spirits of the living, rescuing them from the uncertainties – and misplaced certainties – of modern life, and recalling them to older, more natural and fulfilling ways of perceiving and living in the world.

Fast-forward a century, and in the shadow of the disasters of 2011 – earthquake and tsunami, followed by a nuclear meltdown – the ghosts of Japan seemed once again to be up to something new.

A narrow road winds around and around, steadily upward through lush forest. The greenery gradually thins out, giving way to a lake set in a lunar landscape of blasted white rock, under an enormous slate-grey sky. The occasional thin spurt of steam escapes from gaps in the rock, while elsewhere pieces are piled upon one another – into mounds about a metre high by several metres wide. At first sight, these look like deposits of rubble. In fact, they are cairns, in memory of people who have led the shortest of lives. Young couples pace around them, not saying very much. Poked into the tops of the cairns, alongside statuettes of Jizō, protector of children and voyagers, are plastic toy windmills, in cheerful shades of pink, blue and yellow. Something for babies and children to play with, on the other side.

A Jizō statuette with a warm hat and baby’s bib, Okunoin cemetery, Koyasan. Photo by Scott Flockhart

This is a place caught between the living and the dead: the summit of a volcanic mountain known as Osorezan (Mount Fear), situated at the northern tip of Japan’s main island, and long regarded as an entrance to the underworld. Warm vapours waft from the rough, rocky terrain, through the fine-gravelled courtyard and cavernous wooden buildings of a Buddhist temple complex, Bodai-ji, run by the Sōtō Zen sect. Sulphur and incense mix in the air, while a trickle of hot, yellow-tinged water runs beneath a pathway into the temple, built upon wooden stilts.

The effect is one of human endeavour eking out a precarious compromise with something utterly alien and overpowering. Bodai-ji has been here, in one form or another, for most of the past 1,200 years. And yet it feels temporary, like it is just visiting.

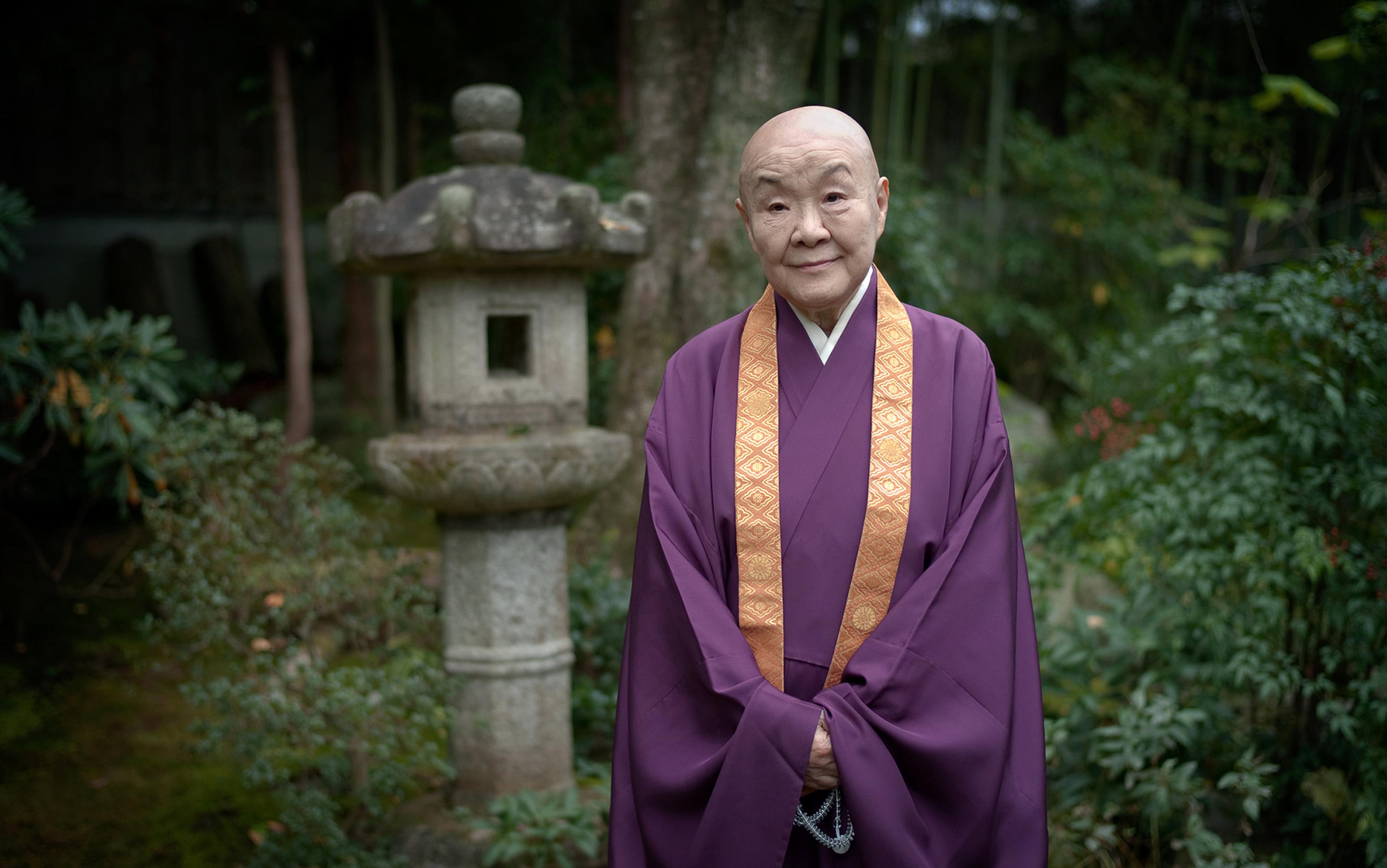

This place has had a powerful effect on the temple’s acting chief priest, Jikisai Minami. He had thought about death since he was young, wondering how such a thing could possibly exist in the world, and obsessed by the idea that though he hadn’t ‘started’ himself, he nevertheless had to live with himself. He discovered the dead as what he calls ‘a very real presence’. ‘They really exist,’ he tells me, as we speak inside one of the temple buildings. ‘Just as powerfully as this table – sometimes even more so. It’s completely different from them existing in memories.’

In the wake of March 2011, the dead played all sorts of roles in bringing comfort to the living. In some quarters, sightings of loved ones who had passed away were understood in terms of secular psychological theories of bereavement and grief. ‘Post-bereavement hallucinations’, as they are known, involve a person seeing, hearing or feeling the presence of someone who has passed away. It is considered a natural and often perfectly healthy means of psychological self-repair – for anyone, anywhere, but especially in such places as Tōhoku where an ageing population is often more at home with spirits than with psychologists or psychiatrists.

Elsewhere in Tōhoku, an indigenous female shamanic tradition well over 1,000 years old offered help of another kind. Whereas the festival of Obon is a celebration of business successfully concluded – the living and the dead doing right by one another, in a reasonably settled relationship – the 2011 tsunami created sudden ruptures that were very hard to heal. There had rarely been time for goodbyes. In these circumstances, a shaman was able to help supply that missing piece of a relationship by calling up the spirit of a client’s relative and speaking with his or her voice: reassuring them that the deceased is contentedly at rest, and is watching over their families from the other world.

Minami’s take on the ‘reality’ of the dead is different again. He gives the example of a woman who died in the 2011 tsunami, leaving behind her husband and her nursery-age daughter. It was difficult at first for Minami to offer them any help in their grief because neither father nor daughter were able to talk about the mother:

The daughter thought that if she talked about her mummy, her father would be sad, so she held it in and kept quiet. The father, too, kept quiet about his wife, so as not to upset his daughter. So neither of them spoke about the person who had meant the most to them. It wasn’t getting them anywhere.

The mother was still too real a presence, says Minami. And though this might sound like simply an exceptionally vivid recollection, Minami insists that it isn’t just that. Nor is he interested in the possibility of spirits being recalled in the more literal sense of the shamanic tradition. Talk of ‘spirits’ or ‘souls’ is often too trite, too easy, he says. Instead, he makes a distinction between the real and the virtual. The virtual can be switched on and off. You remember someone by ‘conjuring them up in your mind, on demand’. The real is very different: a person is there whether you like it or not – ‘regardless of your actions, intentions, or feelings’.

‘In North Korea, there’s nothing more real than the deceased first and second dictators’

This question of whether a person is ‘real’ or not seems, for Minami, to supersede that of whether or not they have bodily life. A person who is alive but totally unknown to you is not, he suggests, real in any meaningful way. And yet someone who is dead can exert enormous power – and this applies not just to loved ones. He gives the example of North Korea, whose missiles have passed overhead not far from Osorezan in recent years. ‘In that country,’ he says, ‘there’s nothing more real than the deceased first and second dictators.’

That Minami is talking about more than memory, bidden or unbidden, or about legacy, within a family or within a nation, becomes clear when he applies his analysis not just to talk of the dead but to the living too. Grief or ‘survivor’s guilt’ – especially after a tragedy on the scale of the 2011 tsunami – contains, he argues, an important reflexive element, which can be easy to miss. Sufferers encounter afresh, or perhaps for the first time, the problem of their own existence. They face the question not just of why someone else died, whereas they are still alive, but why they are alive in the first place: ‘They don’t know why they’re here; they don’t know why they were born; they don’t know why they will die. It’s directly linked to basic existential angst.’

This is partly where our appetite for ghost stories comes from, says Minami. Bad ones are ‘so conventional; you lose that vivid sense of reality’. Good ones point us towards a well-founded anxiety about the stability of our own existence. These do not necessarily induce a fear of being close to death or of our existence coming imminently to an end, but rather indicate something suspiciously thin or fragile or insubstantial about that existence to begin with, like that of Osorezan among the rocks:

The living aren’t that real a presence … You being yourself is an extremely fragile proposition. Meaning that you can’t say that the living are real and the dead are virtual. They’re the same. There’s no real basis for either. They’re not particularly real and not particularly virtual. From my point of view, they’re the same.

For film fans outside Japan, talk of the country’s ghostly tradition might well call to mind a single, terrifying sequence: Sadako Yamamura in the film Ringu (1998), climbing sodden and malevolent from a well, dressed in her white burial shroud, dark hair matted against her face. Once again, a subtle unease at 20th-century technology was helping to power ghost stories along. Decades earlier, it had been the telephone. In Ringu, it’s a videotape that must never be viewed.

The J-horror genre, populated by terrorising, grudge-holding ghosts, and drawing heavily on Japan’s kabuki tradition, is celebrated – and much imitated – around the world. But are the ghosts of Japan now firmly embarked on a one-way journey out of the land of the living – banished not to some other world, but into an oblivion of consumption, irony and eventual indifference?

If so, then in one respect Yanagita might have been right to fear for the people of Tokyo and Osaka, back at the beginning of the 20th century. For all that his country was beginning to achieve in that era, by importing and developing for itself new technologies and ideologies of human mastery in the world, this process risked the steady fading from memory of perhaps the most important question that Japan’s ghosts have been capable of inspiring: not so much ‘Are they real?’ as ‘How real are we?’

It is a question still asked at the summit of Osorezan. But it dissolves quickly as you descend, returning to the reassurance of tarmacked roads, streetlamps and Japan’s ubiquitous 24-hour convenience stores. A world built by human hands, on a human scale, and with human purposes in mind naturally serves to strengthen the myth of mastery to which Yanagita worried that Japan would succumb – reinforcing a version of ‘me’ like the one that, back up at the top of the mountain, had briefly been cast into doubt. No wonder remote mountaintops are powerfully associated, in so many cultures, with epiphanies and purity: everyday life down below rarely reveals itself as conjured, as ‘virtual’. It, and I, feel real enough.

Taxi drivers respond to ghost passengers not with the fear of earlier eras but by taking them where they need to go

And yet perhaps Yanagita underestimated our need to balance mastery with mystery. We seem to be made for both. J-horror would not get very far without the fuel provided by people’s unquenchable curiosities, doubts and worries about the world: about the darker sides to human life. About the pain that we inflict on others – generating grudges we cannot outrun forever. Even about a hidden world more fundamental than the one we deal with on a daily basis, in which there might be more shade than light.

In Japan, some wonder whether an eventual effect of the traumas of 2011 might be a slight recalibration of that balance; the kind of deep cultural shift that becomes visible only in retrospect. They note a broader context in which a secular, baby-boomer generation has, against all expectations, been giving way to a younger one more interested in ‘spiritual’ ideas and practices. And they point to taxi drivers in Tōhoku, responding to their ghostly passengers not with the fearful placation of earlier eras but by engaging with them almost as they would with the living: listening to what they have to say, taking them where they need to go. These ghosts appear less like the spectral nightmares of kabuki or J-horror, and closer to the kinder, more complex and uncertain spirits that feature in the country’s minimalist Nō theatre (an artform historically patronised by samurai, who had put enough people to the sword that they didn’t much care for tales of the vengeful dead).

Whether or not such a shift will happen, when, and what it will look like if it does, is a mystery in its own right. For all that people not so long ago expected human societies to follow similar trajectories and eventually end up at the same place, in terms of their politics, standards and beliefs, recent years suggest something else: national stories, no less than individual ones, feature unpredictable twists, turns and reversals. Had Fukuji really seen what he thought he had on the seashore? If so what might happen next? Herein lay some of the truth and value of Fukuji’s ghost story: an experience of life’s deep indeterminacy and lack of resolution, which we would be all the poorer for trying to live without.