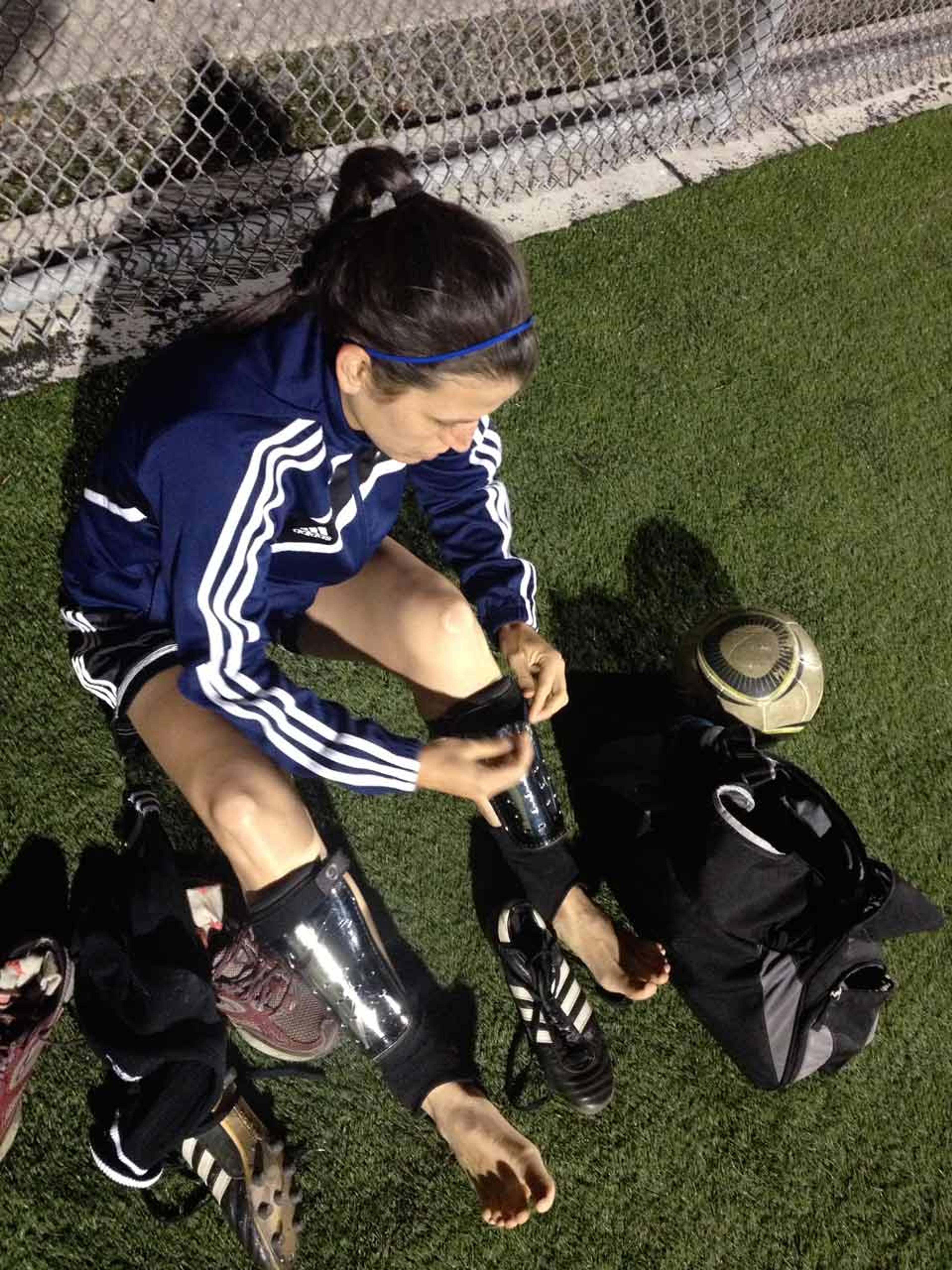

It’s a late summer day in 1998 during pre-season training for the women’s soccer team at Seattle University. I’m 17 years old, a freshman fullback on the up-and-coming National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) team. After a lackluster start, I’m working to prove myself. I’ve let nerves shake my confidence and I can see both my coach and fellow teammates look at me as if to ask why I’m here at all.

We’re doing a drill and I’m standing with my back to a lanky senior. Another player is poised to send me a pass from 10ft away. This exercise should be simple: don’t let the senior steal the damn ball from behind. She towers above my 5ft 5in frame and throws her bony elbows. I get low and try to cut off her angle. The ball comes sliding into my feet and suddenly she loses her balance and lurches forward into my back. I fall face-first toward the ground. My chin absorbs the impact of my body and hers.

The grass and goals are spinning when I stand up. My vision is laced with black spots. It is alarming, but I make an athlete’s calculus, measuring these symptoms against the need to show some grit to this skeptical audience. After a brief break, I rejoin practice. Passes and players ricochet past me and I can’t get anywhere quick enough. I can’t read plays as they unfold. The black spots linger. I’ve slammed my brain hard against my skull.

About 250,000 young athletes are treated annually in an emergency room for a sports-related concussion. Those with the luck to avoid our fate fear that it is only a matter of time before an off-kilter tackle or mid-air collision comes for them, too. They know that a concussion can cause lasting damage, forcing them to choose between their brain and being a competitor who refuses to quit.

Back in 1998, I don’t yet grasp this agonising choice. After practice, I’m taken to a local hospital and a technician scans my brain. A doctor tells me it is bruised, a turn of phrase that’s now considered inaccurate; bruising literally means the organ is hemorrhaging, and mine apparently is not. At the time, however, it’s a powerful diagnosis, and I’m spooked.

In the coming days, the doctor says, I can expect dizziness, nausea, headaches, fatigue. I might find it difficult to concentrate or focus. I might consider having someone wake me through the night since some evidence – now disproved – indicates that concussion victims can lose consciousness or slip into a coma. I should rest and avoid taxing my body or brain.

I expected to be spun out by headaches or wobbly walking down the hallway. Instead, the sensation was one I could barely explain. My brain was strangely quiet. I cannot recall even a single headache, but my mind seemed like scraps of paper that had scattered in the breeze. I was not myself, a person buzzing with thought. I was drifting, but at least it was painless. Within a week of the injury, it seemed safe to step back on the field.

I was wrong.

Every sprint and fake and pass – these simple motions that usually pumped me full of adrenaline and pride – sent shockwaves to my brain. When I tried to move quickly, it felt as though I had just stepped off a Tilt-a-Whirl, the world rotating out of sync with real time. I was lost on the field, with no purpose to my body’s off-rhythm movements. I was useless for the first time in my life.

Cleats pressed into the grass, looking at the chalked lines, I knew it: I was broken, my brain was broken. And I could not stop what was coming. Even as I recovered, this concussion was about to worm its way through my life and steal the sport that I loved.

When talking about the end of my soccer career, I can barely spit those last two words out. They sound formal and flat and, like a photograph, can impart only the image, but not what it meant to be there. I wore the dark tan between my shorts and shin guards proudly. If a spontaneous pick-up game started and I didn’t have cleats, I played in sandals. As a teenager, I turned down alcohol and cigarettes so I wouldn’t risk sabotaging my fitness. I knew I would eventually be something else in life, but I was first and always a soccer player.

That meant more than can be conveyed by this two-syllable, hard consonant word. With the right teammates, soccer is an electric current and there is an art to how the game flows. Passes are elegantly strung together based on each person’s talent and intelligence. The game unfolds in time and space as the team searches for the right way to crack a defence or hold possession in the midfield. On the best days, the collective performance is equal parts grace, brilliance and determination.

A girl might shout directions such as switch it or drop or square, but the greatest plays are unspoken. Even if a fellow player is obnoxious or petty off the field, you know where she is and where she wants to go. You find her in your head and then at a diagonal pass or by lobbing the ball over the defender, and she does something beautiful in turn.

You must be technically gifted to feel this hum, but it grows stronger with practice. If the conditions are right and your teammates are also skilled, the game becomes meditation and the static of life’s uncertainties drops away. In that place you can command a power that exists nowhere else in daily life.

Sometimes it feels like a song. First the sound of cheering parents cuts out and you hear it clearly: that piece of music you played on the cassette player while warming up. As a teenager, I had Pearl Jam’s Breath and Porch and Corduroy in heavy rotation. It was always the bridge I’d hear, that 30 seconds or so of guitars whining and then wailing, the bass blowing out, the high hats and snare crashing, the solo ripping through it all.

I wanted to own myself, and there was nowhere else to do that but on the field. I was a badass bringing down an attacking forward in a one-on-one

And then suddenly I was the song in all its orchestrated fury. My body was an instrument and I could riff or harmonise or wail with every play on the field. My brain sent me hurtling into space because it knew what was about to happen. I could fall deep into this rhythm and count on at least one transcendent moment where every shred of hope and rage and brilliance I could muster was expressed in a single play.

The power of the defender’s job is addictive. I’m not big enough to be a bruiser, but I can destroy forwards. I size them up and summon a will made of black magic and skill. I read the play in the midfield and short-circuit the girl I mark, stepping in front to steal the ball or clinging to her like a leech. I want to make my mark suffer. I want her teammates to stop passing to her. And if we battle and I recover the ball, I’ll sprint half the length of the field, overlapping the midfielders and positioning myself for a pass at the corner flag. I’ll wind up, rotate my hips, and let loose a perfect cross to the scrum of players in the goal box.

It’s easy to let these moments become a story to tell about who you are: I will slide-tackle to keep the ball in play; I will hurl my body against an opposing player who fouled my teammate; I will last four 90-minute tournament games in the 110-degree sun; I will send to our best forward the game-winning assist. There is no end to what I can do.

What I wanted from my sport was not a career, but an identity. I began playing at six, though I was no prodigy. It was just what our family did. My mother coached. My older brother and sister played. So I did, too.

I still remember the hot August practice at an elementary school field in a Sacramento suburb when, at 12, I first felt the high of soccer played well. I was wearing jean shorts and a tank top, like most of the girls on the field. It was so warm that we weren’t wearing socks over our shin guards. We were not the kind of athletes who had been groomed for club play. But as I stood in the midfield and became part of a simple string of passes that created a forward momentum, I wanted to hold that feeling forever.

The timing happened to be perfect. That year I began to brutally wish away the desire for things I could not have, like black velvet Vans sneakers and Guess jeans. I was tired of how our family lumbered from paycheck to paycheck. And I wanted an independence not easily given to young girls whose fathers are second-generation Mexican-Americans. Your dad might love you, but you do as he says, or you don’t do anything. I tried bargaining a new identity, offering a straight-A report card for permission to skip church. No deal. I was born into his culture and religion.

I wanted to own myself, and there was nowhere else to do that but on the field. I was a badass bringing down an attacking forward in a one-on-one. I became selfish, tearing up the flank in an overlapping run just to score. But I also relished my role as a defender. I wanted to be tested. I needed to lay myself out protecting the goal.

Then my brain broke.

I stopped playing to heal. Like a compass stripped of its magnet, I found that everything I knew about my sport and myself had changed.

It turns out that what I went through then was normal – but in the distant year of 1998, my coaches and doctors didn’t know enough about traumatic brain injury to explain what was happening, and neither did I.

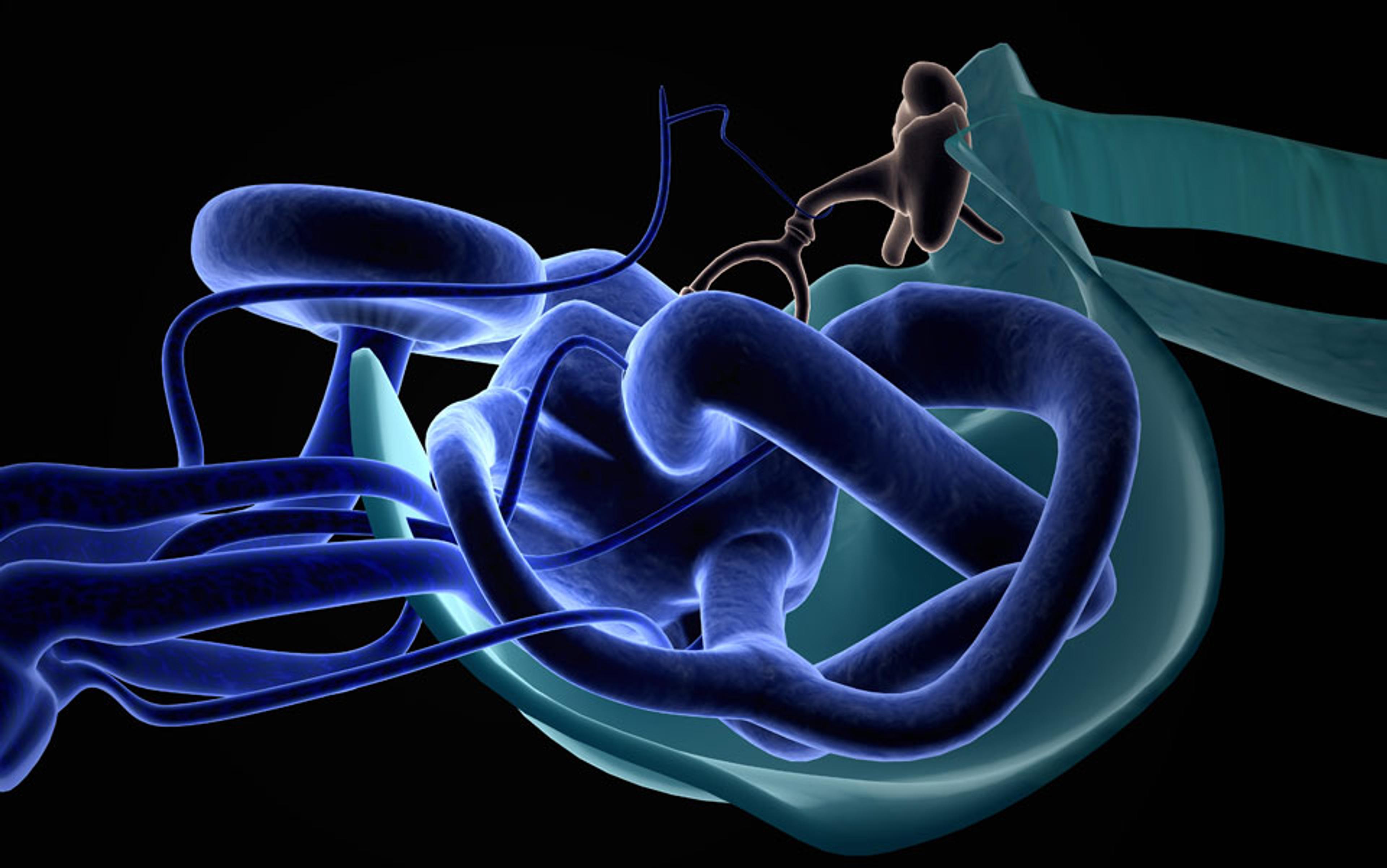

When a concussion shakes the brain, it triggers a cascade of cellular and molecular changes. Mayumi Prins, a neurobiologist with the Brain Injury Research Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, has spent much of her career concussing anesthetized rats and analysing the effect on their brains. While an animal model is no substitute for studying the human brain, her experiments show what happens when biomechanical force is applied to a mammal’s most vital organ: the fibres connecting neurons in the brain can be disrupted or damaged. Until the brain recovers, this short-circuiting dampens the brain’s connectivity, explaining the eerie silence I recall. At the same time, the glucose that fuels the brain is diverted into alternate chemical pathways, away from energy production. It’s as if the brain is managing a traffic jam, Prins says, and glucose is taking a detour as a result. The strategy appears to limit DNA damage from destructive free radicals released by injured cells – but it also slows brain metabolism, substantially disrupting function and thought.

This crisis explains in part why the concussed brain struggles at cognitive tasks such as memory and learning. But a concussion can also leave a person feeling unhinged by creating chaos in the body and spirit. Patients commonly report headaches, sensitivity to light or noise, and feeling sluggish, emotional and nervous. For some, slumber doesn’t bring reprieve; instead, they might sleep more or less than usual, or have trouble drifting off.

Those watching a concussed athlete might notice delayed motor skills that look like poor balance and clumsiness. Though scientists don’t know why, a concussion can hamper the vestibulo-ocular system, the part of the brain that makes sense of the surrounding environment and how the body interacts with place and time. Often, this symptom lurks quietly until exercise, when movement and metabolism tax the brain and everything laid out in front of you seems fragmented. This was the signature symptom of my concussion, and it was bittersweet to hear several scientists talk about new therapies that help athletes improve their balance and vision.

When I was concussed 15 years ago, basic science focused not on my kind of relatively mild injury, but on the violently concussed brain. In sports, that research went back to 1928, when Harrison Martland, a New Jersey pathologist, studied prizefighters who appeared ‘punch drunk’ after enduring ‘considerable head punishment’. These men often staggered back to the corner of the ring, and fans called them ‘slug nutty’ and ‘cuckoo’, Martland wrote in The Journal of the American Medical Association. Extreme cases presented with an oddly tilted head, a backward swaying of the body, and a face contorted in the manner of a Parkinson’s patient. The condition was progressive, Martland added, sometimes culminating in mental deterioration so severe it required ‘commitment to an asylum’.

It was a London neurologist, Macdonald Critchley, who, decades later, coined the term chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE – a disorder of the brain caused not by a tumour or infection, but by repeated bludgeoning. Critchley described a condition he called ‘groggy state’ that rendered boxers confused, and impaired their speed and accuracy. The suggestion ‘that an accumulation of groggy states leads to a permanent punch-drunken clinical picture is not to be considered far-fetched,’ Critchley wrote in the British Medical Journal in 1957.

In the years that followed, scientists proved that repeated injury to the head could drive boxers into a neurodegenerative state resembling dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. But the boxers’ plight, while evocative of those disorders, appeared to be distinct. Indeed, in 1996, just two years before my own brain broke, physicians at the Royal London Hospital conducted an autopsy of a 23-year-old boxer, finding his brain was awash in neurofibrillary tangles – the twisted threads of protein that cluster around neurons, dulling the brain’s ability to send and receive electric signals. As the protein accumulated, it created plaque, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Yet unlike the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, the boxer’s brain was not shrivelled and the large anatomical structures were intact. The doctors suggested that the mechanism for tangle formation here was repetitive head injury, and that the condition represented something brand new.

A concussion can also leave a person feeling unhinged by creating chaos in the body and spirit

Yet boxing, in which brutal hits upside the head are standard, was deemed a sport unto itself – each concussion inflicted on the boxer came from a powerful new blow. Mild concussions such as mine, on the other hand, were seen as largely inconsequential. Imaging technology of the day seemed to back that view. MRI and CT scans did not reveal any malicious effects of a so-called minor brain injury, and the condition was considered benign. Physicians simply couldn’t come up with a neurological or biological reason to explain our symptoms, and we were often treated and advised inconsistently as a result.

I vaguely recall answering a series of questions about my symptoms, and a physician warning to stay alert to muscle weakness or repeated vomiting as ominous signs. But the doctor did not mention the possibility that I might fall into an unfortunate group of patients – about 10 to 20 per cent of the mildly concussed – who experience nagging but non-life threatening symptoms for weeks to months. No one told me not to worry, and the school’s trainer actually urged me against playing until my symptoms were gone. Yet the overwhelming unspoken message in 1998 was that I should have gotten better much sooner than I did.

Four years later, during a Saturday morning autopsy by a medical examiner in Pittsburgh, things would start to change for the concussed. Lying on the table was 50-year-old Mike Webster – the famous ‘Iron Mike’ who had played in the NFL (the professional American football league) for 17 years, most of them as center for the Pittsburgh Steelers. A heart attack killed Webster in September 2002, but his death certificate listed post-concussion syndrome as a contributing factor. This athlete, a member of the US Pro Football Hall of Fame, had been concussed multiple times during his career on the field, and spent the decade before his death in physical and psychological agony. He was severely depressed, became addicted to drugs, and sometimes couldn’t find his way home.

Bennet Omalu was the neuropathologist on the case. A native of Nigeria, he knew little about American football, but nonetheless suspected that the sport had played a pivotal role in Webster’s mental deterioration – much like it did for boxers. Upon opening up Webster’s skull, Omalu told the PBS TV programme Frontline last year, he expected to see a shrivelled brain with features of Alzheimer’s disease. Instead, Webster’s brain looked normal. Omalu felt certain that something was amiss. After all, how could a 50-year-old act demented but not have the signs of such a disease etched into his brain?

To solve the mystery, he stained sections of Webster’s brain tissue and affixed them to slides. Upon examination, Omalu found that, like the boxers, this American football player’s brain was marked by neurofibrillary tangles. Now not just boxers but also football players were said to have the new, progressive brain disorder, and in 2005, in the journal Neurosurgery, Omalu was the first to document the danger of repetitive brain injury in American football, and brand this form of CTE a devastating neurodegenerative disease.

Omalu had powerful adversaries. The Steelers and the NFL challenged his findings. And the league’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee called for a retraction of his paper, which broadly contradicted their own conclusions. Indeed, while Omalu was proposing a previously unrecognised neurodegenerative disease that could worsen with each subsequent brain injury, the Committee was reporting evidence that concussed players could be sent back to the field within the course of a single game at no increased risk.

Most brains can compensate for the suspected long-term effects of one or two concussions, leveraging neurons and ‘cognitive reserve’ to execute daily tasks

Though unpopular on the playing field, Omalu’s results were finding support in the lab. At the Boston University School of Medicine, researchers began documenting CTE in similar cases using the post-mortem brains of male soldiers, football players and hockey players who had sustained mild repetitive concussions. As part of the newly formed Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, the team called a press conference in Florida days before the 2009 Super Bowl to announce that it had found evidence of CTE in the former Tampa Bay Buccaneer Tom McHale. He died of a drug overdose the year before, at just 45 years of age; he was the sixth NFL player whose brain showed CTE.

A few years later, in 2012, the researchers published a powerful analysis documenting CTE in nearly 70 brains that had been mildly concussed multiple times. The authors were careful to stress that their findings could not be used to guess at the prevalence of CTE in living athletes and veterans. Family members who noticed drastic behavioural changes were more likely to donate a loved one’s brain to the study. Moreover, the symptoms that show up in CTE can overlap with those related to drug and alcohol abuse, confounding scientists’ efforts to pinpoint cause and effect.

But the Center’s most germane research, as far as I am concerned, came out just this year. The neurologist and pathologist Ann McKee and her colleagues examined the brain of Patrick Grange, a former semi-pro soccer player who died in April 2012, at just 29. Grange was five when he learned how to head the ball, and went on to compete in high school, college and in the Major Soccer League. He did this, his parents told The New York Times last month, despite sustaining at least two significant concussions: one collision in college left him with more than a dozen stitches in his head. At 27, Grange suddenly developed fatigue and weakness in his limbs, and was diagnosed with the neurodegenerative condition amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). When McKee looked at Grange’s brain, she saw CTE and extensive damage to the frontal lobe. Grange is the first named soccer player to have been posthumously diagnosed with CTE.

Despite the new findings, the study of CTE is still in its infancy. The neuropathologist Eric J. Huang, who specialises in neurodegenerative diseases at the University of California, San Francisco, says that the relationship between abnormal protein aggregation and changed behaviour in patients with CTE is like a ‘black box’. In some cases, the clusters appear in sections of the brain that regulate emotion –other times, they don’t. Scientists aren’t entirely sure why the plaque builds up in the first place. One hypothesis is that multiple concussions damage nerve fibres, provoking a biochemical cascade that generates abnormal protein buildup at the end.

Huang adds that we might not even have a clear definition of CTE. After all, what we know about neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s comes from decades of research involving many patients. ‘From a pathology standpoint,’ Huang says, ‘we like to see a large number of cases before we reach a conclusion about the diagnostic features.’ By that count, scientists need to diagnose CTE in hundreds more patients and observe the same features over and over again before the contours of the disease – its signs and symptoms and various outcomes – are truly understood.

Yet insight into mild concussions – and what could be a less deadly form of CTE – has begun to emerge. Important finds come from the neuropsychologist Dave Ellemberg and his team at the University of Montreal. The researchers recruited about 40 former university athletes in their 50s and 60s, splitting them up evenly into a healthy group and another that had sustained concussions decades earlier. The injured showed significant reductions on neuropsychological measures for memory, attention and decision-making.

Those cognitive deficits can look like everyday lapses – for example, difficulty in organising one’s schedule or grocery list, or struggling to improvise when plans suddenly change. For these people, the mind can become rigid, explains Ellemberg, co-author of a 2009 Brain study on his team’s research. He says that most brains can compensate for the suspected long-term effects of one or two concussions, leveraging neurons and ‘cognitive reserve’ to execute daily tasks. These resources are akin to extra credits that run out as we age. ‘Every time we have a concussion when we’re young,’ he says, ‘we’ve wasted these credits.’

Women are even more sensitive to concussion than men. Cindy Parlow Cone played striker for the US Women’s National Team. At 5ft 11in, she was a monster in the air: 158 appearances and 75 goals between 1996 and 2004 make her the USWNT’s sixth leading all-time scorer. For that record, she trails the game’s most accomplished women – Mia Hamm, Abby Wambach, Michelle Akers – all of whom competed for more than 10 years.

One day in 2001, while playing in a televised game for the now-defunct Women’s United Soccer Association, she went in for an easy header just outside the goal box. Her feet barely came off the ground. A teammate unwittingly did the same thing. The two collided midair and fell like ragdolls.

In the footage, which is featured in the documentary film Head Games (2012) about repeated concussions, Cone lays on the ground stunned. It wasn’t her first concussion, but it did briefly knock her out. After the game, headaches dogged her for a few weeks. Then she was back at it.

Except then, Cone tells me, every time her head connected with the ball on a long goal kick or strong cross, she saw flashes of light that looked like stars. By her count, this happened more than 100 times over a three-year period. And during that time, she was beset by recurrent headaches, fatigue and lockjaw.

A decade ago, a concussion – or two or three – was not career-ending, at least publicly. Akers, a USWNT legend, suffered numerous concussions, like Cone, most famously during the 1995 Women’s World Cup versus China, but she never sat out for long.

Now we know that female athletes in particular should be watched closely after a concussion. A handful of recent studies have shown that they are more prone to brain injuries than male athletes and can take longer to recover. In 2007, for the first study of its kind, Ellemberg and his team compared 10 female university soccer players who had sustained a single concussion with a dozen who were healthy. Ellemberg found evidence of cognitive impairment six to eight months after the first concussion, well after the players’ conscious symptoms had subsided. While they did well on verbal learning and memory tasks, they were slower than the control group at switching between activities, and needed more time to make a rapid decision on a complex matter.

At just 26, she retired from the sport. It might be decades before Cone knows whether she quit early enough

Women might report more severe concussion symptoms compared with men as a matter of culture – they’re more likely to discuss vulnerability or weakness. But, Ellemberg says, the disparity could come from differences in the male and female body. A woman’s weaker neck and torso muscles might mean she can’t absorb a blow to the head as efficiently as a man can. It’s also possible that the hormone oestrogen actually has a detrimental effect on concussion recovery.

Scientists still don’t know just why females face greater risk, but in 2012 researchers discovered that female high-school soccer players have a concussion rate lower only than that of male players of American football, ice hockey and lacrosse. A JAMA Pediatrics study published this January found that concussion rates among middle-school female soccer players were actually higher than those reported in older age groups. Their symptoms included memory loss, nausea and difficulty concentrating.

This is the science I wish I had in 1998; before this ground-breaking research, you never opened the newspaper to read about the latest professional athlete whose life unravelled, a history of concussions stalking in the shadows. Contrast with today, when trainers and physicians use several detailed scales and checklists to make an accurate diagnosis. Players are even assessed pre-season so that their baseline scores on balance and cognition can be compared with post-concussion performance. These measures are an attempt to get objective data from a patient instead of relying on her description of symptoms, which she might sanitise if it means getting back onto the field. I was rightly cautious so many years ago, but how I wish I’d had studies to vindicate me at the time.

But then maybe science isn’t that empowering. A recent report on youth concussions from the Institute of Medicine in Washington DC found that a culture of ‘play through it’ still permeates organised sports. The panel, which included Huang and Prins, wrote in October 2013 that despite increased awareness about the risks of head injuries, athletes still resist reporting concussions and don’t always comply with orders to rest. The JAMA Pediatrics study found that more than half of the injured young girls continued to play.

Even Cone, plagued by symptoms and unaware of long-term risks, played until she couldn’t. The end, she says, probably should have come after the 2003 World Cup, where she suffered another debilitating concussion. At the 2004 Olympics, she played with daily headaches and constant fatigue. Then a neurologist laid it out: ‘I’m not going to say you can’t play,’ she recalls him advising, ‘but I can’t tell you if you suffer another concussion how bad it’s going to be.’

After getting the ominous news, Cone was ‘a little bull-headed’ at first, training even when the headaches wouldn’t stop. But then, at just 26, she retired from the sport. It might be decades before Cone knows whether she quit early enough.

In the years since her retirement, Cone’s symptoms have improved. The headaches and fatigue come less frequently. She plays pick-up games occasionally, but never heads the ball. She tries not to think about the tragic stories of football and hockey players whose lives became so tattered that they eventually broke apart. Research is important to her, though, so she became the first female athlete to donate her brain to Boston University’s post-mortem study of CTE.

For Cone, the long-delayed choice to quit didn’t culminate in a struggle to understand who she was without soccer. Though she poured every bit of her will into being a world-class athlete, it did not swallow her whole. ‘I wasn’t losing everything that I was,’ she says.

It wasn’t like that for me. I waited three long months for my symptoms to subside. During that period I became, for the first time in my sport, an interloper, a red-shirt with a lame excuse for warming the bench. I watched a junior midfielder I’d heard had been concussed continue to play even after a new blow to the head left her noticeably disoriented. I wondered what stopped me from doing the same. I doubted myself, wondering if I was being too sensitive to the dizziness and imbalance, or if the concussion was still lodged somewhere in my brain.

This invisible injury frays the bond between teammates. I felt some of mine looked at me as less of an equal. A few asked me to retrieve balls during practice, a bald-faced insult for a player with a sprained ankle or a hamstring pull.

I describe this experience to Jill Brooks, a clinical neuropsychologist with a private practice in Gladstone, New Jersey. When athletes walk through her door, it’s usually because they have seen several other doctors, but have gotten no reprieve from their concussion symptoms. Instead, I need her to help me understand why I couldn’t keep playing even after I’d recovered.

I recount the first week of morning practice in January 1999. My symptoms had vanished and I was cleared to play. We scrimmaged indoors in teams of three or four. I connected passes, made plays and defended with rote technical precision. I should have been exhilarated. Even a few of my teammates seemed to register surprise; I was suddenly the player I was supposed to have been. My brain was finally free and it was safe to play, yet I felt no surge of relief or satisfaction.

I had crawled deep inside my head to find an imposter: I didn’t have the heart of an elite competitor anymore

At some point in those months spent as a red-shirt, I chose to protect my brain and no longer yearned to sacrifice it for soccer. I became cynical about belonging to an athletic sisterhood that had no use for its injured. I tired of proving myself. I didn’t want to devote every week to practice, games and travel.

‘This is about grieving a loss in many ways,’ Brooks says of concussion recovery. An athlete’s life is made up of dependable rhythms and endorphins from which you derive purpose and happiness. When this vanishes for too long, dark thoughts can overwhelm the mind. This was different from the quiet I experienced directly following the concussion. It felt more like the tentacles of depression tightening around my brain.

For years I’d thought of this as a failure of mental fortitude, but research now shows that concussed athletes often feel depressed. The causal relationship, though, is hard to disentangle. It’s possible that a head injury affects parts of the brain that help regulate mood. But sadness and anxiety might also be a natural response to the shock of a hobbled brain. A 2012 study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation evaluated 75 concussed athletes in the two weeks following their injury and found increased levels of depression. This dissipated for high-school students after 14 days, but persisted for college athletes, perhaps because of scholarships, elite competition and other high stakes.

For me, the concussion and the depression it ushered into my life crushed my love for the sport. I had crawled deep inside my head to find an imposter: I didn’t have the heart of an elite competitor anymore. Always, there was a voice asking: ‘How badly do you want this?’ Always, there was silence. I once judged others who skipped practice or wilted under pressure as undeserving of the sport, but now I was drawn into that same outwardly apathetic pose. Like falling inexplicably out of love, no explanation made sense.

The visceral sensations that once electrified me turned dull, and I was but a shadow. I hated this hollow place so much that there was no choice but to abandon it. After that week of practice in January, I walked into my coach’s office and quit the team.

Yet Brooks says this psychological drama is common for athletes who are suddenly plucked from a lifelong routine. While I endured this transformation alone, there are now experts such as Brooks who are trained to help athletes heal, not only from the physical damage of a concussion, but also from the psychological scarring.

In the years after quitting, I played recreationally. I’d watch World Cup or Olympic matches and become a soccer player for 90 minutes again. But whenever I got too close to the sport, I felt the loss of this thing that I’d known like nothing else and it haunted me. For a decade, I wondered if I’d made the right choice. I began to imagine an alternate reality in which I returned to play, escaping long-term consequences.

‘Magical thinking,’ Brooks says. ‘Every time I buy a lottery ticket – why can’t I be that one person that wins Power Ball? We’re hoping against hope that we would be the one.’

Last spring, I called my former Seattle University coach Julie Woodward to talk about the past. In 1998, she was starting her second year at SU and, as I recall, had ambitions to compete in the NCAA one day. She had seemed disinterested each time I’d told her I still couldn’t play.

All those years ago, I’d feared what Woodward thought of me as an athlete. When I hear her familiar sunny voice now, I’m ready to ask why I didn’t matter more. But as she listens to my strange journey of regret, my resolve deflates. ‘I can think back and feel a little bit of your pain,’ she says. ‘It was sort of an invisible injury,’ she says. ‘Now, anytime anyone has remotely hit their head, they’re seeing our trainers. I always hear if it’s a concussion.’ Injured SU players are benched until they’re healed.

We talk about what the game means to both of us and I tell her I’m still obsessed: I’ll watch a thrilling match such as the 2012 Olympics women’s semi-final between Canada and the US, and then I’ll go to the local field to dribble, juggle and shoot. I explain how I’ve wondered for years if I was right to sit out for so long.

‘You probably don’t want to hear this,’ she says, ‘but I think for your long-term future, you probably made a good decision. Say it was my daughter, I would have probably encouraged her to do the same thing.’

Her empathy is generous, but regret doesn’t care how many games you’ve played since or that you still dream in soccer. I busted my brain and it broke my heart. The cruelty of my concussion was that it ended the athlete I’d always been. I will never be her again and she will never be me. But we are finally easing into each other, suspicious yet willing to accept that we cannot live apart. We share our secrets, and that impulse to want something so badly you are both vulnerable and unyielding. We know about the feverish devotion to this thing called soccer. We know how it turned a young girl without a lot of power into a wild force. And that what she could never feel in church – the pulse of infinite and divine connection – she discovered on a stretch of grass with a ball at her feet.