Some places make people believe. For nearly a millennium, archaic Greek city-states and diverse cultures throughout the Mediterranean world sought truthful accounts of the future from the Oracle at Delphi. Rival prognostications were available from prophets elsewhere, but none carried the authority of Delphi: you had to climb to the base of Mount Parnassus for the preferred truth. Upon arrival at the sanctuary, supplicants would walk past lavish treasuries built by those who had come before them, in gratitude for accurate prophecies previously received. Those buildings themselves physically reinforced the idea that divinations received from the priestess at the Temple of Apollo were reliable guides to future events. Who builds monuments to failures?

Oracles such as Delphi have fallen out of favour as homes for legitimate understandings. These days, we build tailor-made places where diverse judgments about different kinds of realities get settled: churches and other sacred spaces for sustaining transcendental verities; laboratories for making scientific claims about the natural world; courthouses for deciding the facts of a case. Such specialised ‘truth-spots’ lend credibility to beliefs or claims that come from there. They are not merely settings where decisions about beliefs and propositions just happen to be made. Rather, through their outward materiality, their geographic location and the stories we share about them, these places contribute actively and vitally to the making of truth.

Ordinarily, truth-spots stay put over time, and those who seek believable knowledge must travel to them – not the other way around. Two millennia ago, the journey to the Oracle at Delphi was a long and tough slog through the mountains, and there were no short cuts. The Temple of Apollo stayed put and its enduring location on remote Parnassus contributed to the oracle’s mystique as the provenance of credible prophecy. In the same way, today’s religious buildings, laboratories and courthouses are stationary places. Once built, none is easily or cheaply moved around, even though copies might be cloned from a single fixed model and built in different places.

But is longevity in a particular location always needed in order for a place to make people believe? Some truth-spots travel: they inhabit a place only temporarily. Sometimes a portable assemblage of material objects might be enough to consecrate an otherwise mundane place as a source for legitimate understandings – but only for the time that the stuff is there, before it moves on. But if a church or lab or courtroom can be folded up like a tent and pitched someplace else, can it really sustain its persuasive powers as a source for truth? Here is how it works.

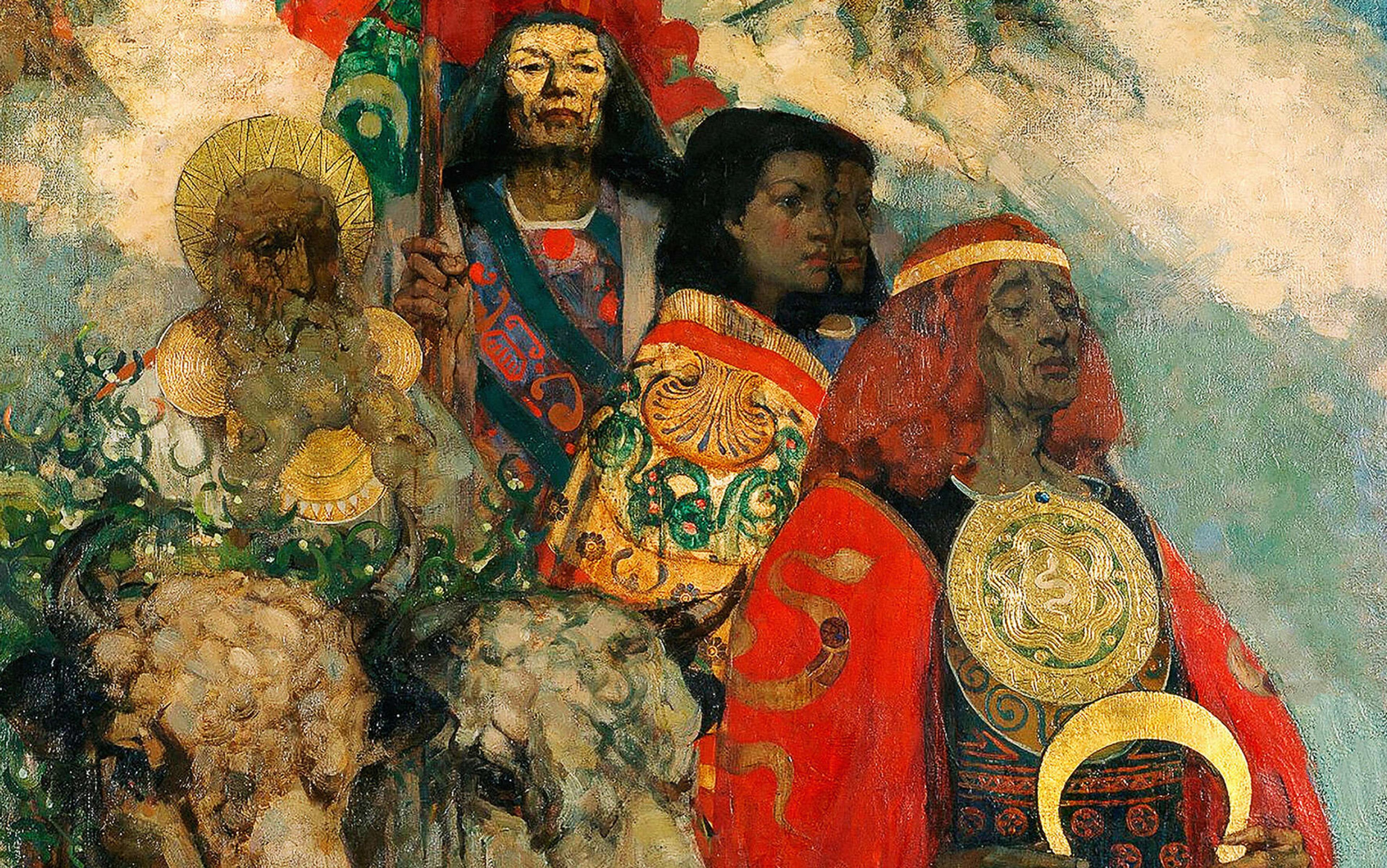

Robert Woods Bliss made a lucky find at a flea market in Madrid in 1961. His acquisitions of pre-Columbian art now form much of the collection at the Dumbarton Oaks Museum, part of Harvard University, in Washington, DC. Back in 1961, he bought what turned out to be a rare and important artifact that begins to suggest how religious beliefs and practices could spread via sanctified sites that are themselves moving from location to location. It is a thin slab of black obsidian set in a wooden frame, measuring about 12 inches by 11 inches, and one inch thick. The exposed surface of the stone is polished to the point where it reflects the faces of those who move in for a very close look. The surrounding frame is gilded, and carved with tendrils and flower rosettes. The obverse is wood, not stone, and carved with the emblem commonly used by Franciscan monks who travelled to New Spain (Mexico) in the early 16th century – looking for converts to Catholicism.

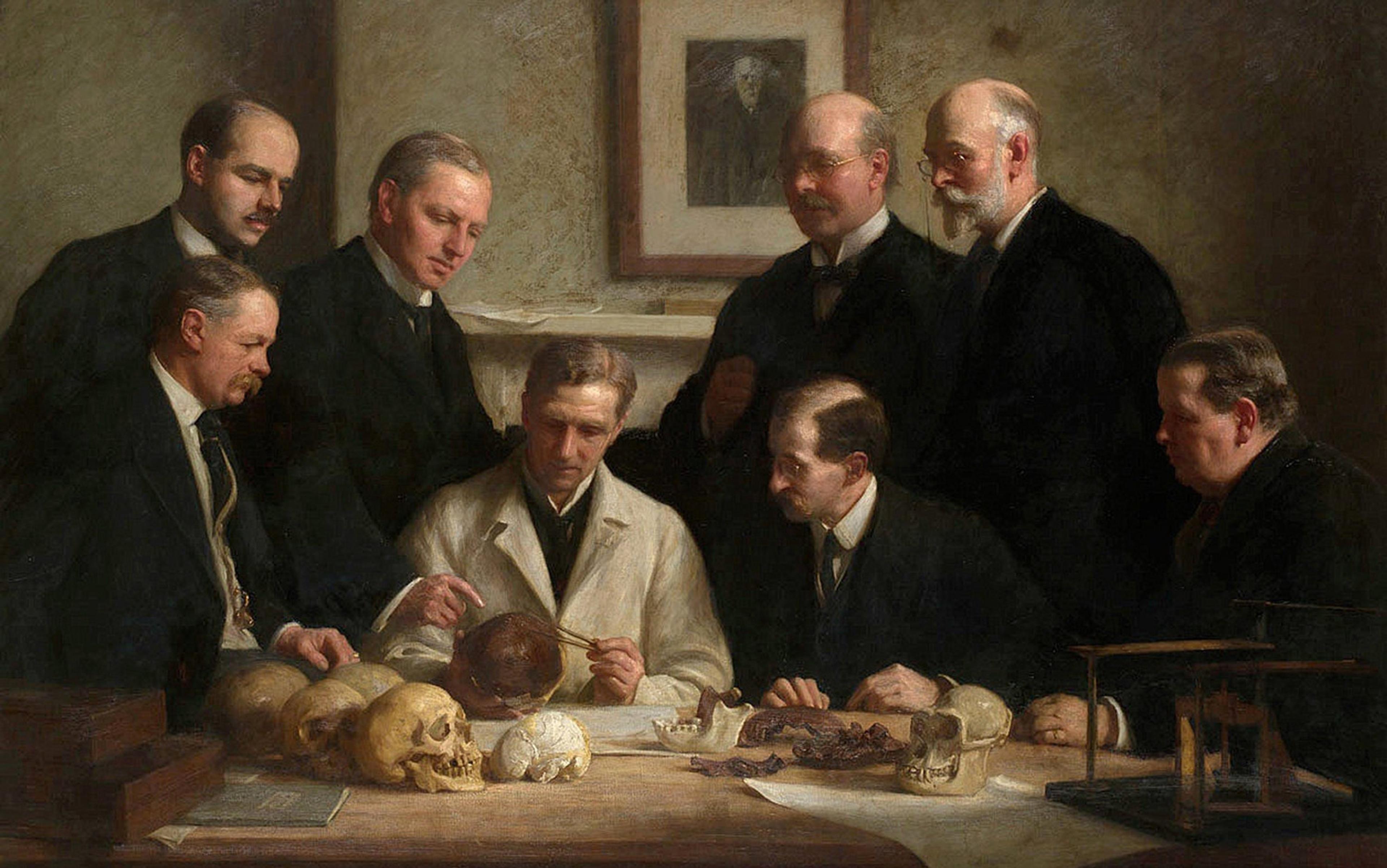

Obsidian Mirror or Portable Altar, Aztec, 1524-1600. Obsidian and gilded wood. Courtesy Dumbarton Oaks, Pre-Columbian Collection, Washington DC

Most archaeologists agree that the piece probably served as a portable altar. Mendicant friars first came to Mexico soon after the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés’s own arrival in 1519. With the Inquisition going on back in Europe, Spaniards in the New World sought not only conquest and gold, but the conversion of indigenous peoples to Christianity. Franciscans faced an enormous challenge: mere hundreds found themselves among more than 1 million Aztecs (Mexican people) living in villages throughout the central valley surrounding their capital city of Tenochtitlan. The monks came upon monumental temples built by the Aztecs as sacred places where gods could be worshipped and appeased with human sacrificial offerings, decorated with the trappings of native cosmic beliefs. ‘Conversion’ of indigenous people to Catholicism would not be easy, but colonial ambitions in the New World depended upon rendering the local population docile, a project that was simultaneously military, political and spiritual. Although armed resistance to the invasion and conquest continued in scattered pockets for decades after European arrival, it declined rather quickly – even before a pandemic wasted perhaps as much as 90 per cent of the Aztec population in New Spain.

The obsidian altar in its decorated wooden frame likely played a role. Franciscans did what they could to destroy the symbolic displays of indigenous religion and, over time, they constructed fixed and lasting churches and missions – often on top of Aztec sacred spaces, reworking the stones for Catholic designs. But conversion efforts could not wait for permanent churches to be built throughout Mesoamerica, and so itinerant monks began to conduct Catholic mass in makeshift open-air ‘chapels’ as they moved from settlement to settlement. Proper Catholic mass – and especially the baptisms that were reported to involve hundreds of converts – did not require a church building per se, but only a space sanctified by symbolic objects: an altar (ideally made of stone), a cross, a chalice for the Eucharist. One can easily imagine a Franciscan friar, upon the conclusion of mass, putting this obsidian altar in his satchel and carrying it to the next village – to perform the sacred rites again.

The portable Catholic altar helped to gain a measure of Aztec acquiescence

We might never know exactly how Meso-American peoples understood these Christian rites, as they gathered around a priest with his portable altar, typically set up near to their own sacred places. It seems unlikely that there was a complete and instant swapping of one belief system for another. More likely, Aztecs watched the performance of Catholic liturgy through the interpretive lens of their own pre-Columbian rituals – and here is where the details of the carved obsidian altar become important. Visible features of this particular altar might have evoked a receptive enthusiasm among the native congregants that could reasonably have been read by the priest as divine compliance.

Obsidian possessed a special significance in Aztec cosmologies. The stone was associated with the god Tezcatlipoca, Lord of the Smoking Mirror, and his priests could peer into the shiny black surface and see not just their own reflections but prophetic visions of the past and future. Obsidian was also flaked to make sharp knives that were used in human sacrifices, and the bloodletting might have been performed on sacrificial altars also made of obsidian. Pre-Columbian obsidian was made into round or oval disks with an extended handle that had a hole in it, to hang around the neck of the priests serving Tezcatlipoca. But sometimes it was cut into thin rectangles and polished, just like the one that was eventually put in a gilded wooden frame. In other words, the Franciscans brought to the native people familiar things – not only obsidian but also the carvings on the back of the altar.

The Franciscan emblem in New Spain showed the five stigmata of Christ’s wounds, perhaps understood as the quincunx of the Aztec cosmos. The abundant blood flowing from each hole would surely have been noticed – as would the position of one of the wounds at the centre of the other four, which could have been interpreted as the symbolic altar where human sacrifices were performed. The indigenous ‘converts’ made sense of mass, not necessarily in the Catholic sense, by seeing its material artifacts as ‘like’ those with power and meaning in their own symbolic universe – here adapted to make the new fit into the old. The portable altar thus helped to gain a measure of acquiescence, even if the details of Christian beliefs and practices were not understood by native peoples in a way that the missionaries had hoped.

Clair Patterson (1922-1995) was a geochemist responsible for getting the lead out of the gasoline we pump into our cars. How he managed to accomplish that – up against prevailing scientific theories about the sources of lead in the natural environment, and also up against corporate powers who once had a significant financial stake in the manufacture of tetraethyl lead (an additive that reduces engine knock) – is the story of a special laboratory at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena that migrated to Antarctica for the collection of ice samples.

In the 1950s, Patterson began to suspect that amounts of lead in the air, water, soil and even human bones had been increasing during the Anthropocene period, spewing out from the tailpipes of gasoline engines everywhere. Aware that lead is toxic to humans, Patterson worried that a potentially massive public health crisis was in the making. But how can a scientist ascertain the proportion of lead that is of recent vehicular origin, as opposed to lead that has been around since the formation of the Earth?

You need a very clean laboratory – an ‘ultra clean’ one – capable of eliminating all lead except those tiny bits that get analysed in controlled geochemical experiments. The isotopic signature of primordial lead differs from the signature detectable in lead created recently. By studying the ratio between these two isotopic patterns in natural samples taken from different geo-historical moments, Patterson could discover whether or not quantities of lead are increasing over time. Initially, while working in a conventional chemistry lab at Kent Hall in 1948, one of the oldest buildings on the Caltech campus, Patterson found that his analyses were contaminated by the lead that was simply ubiquitous. He designed and built an innovative clean lab, controlling all incoming air and water to the highest standards of filtration. His experimental equipment was bathed in acid to rid it of lead contaminants, all reagents were super-purified, and researchers entering the lab donned moon suits (lead accumulates in our hair) – even the floors and walls were routinely scrubbed with hyper-distilled water.

He reproduced the immaculate conditions of his California lab on the ice shelf in Antarctica

But Patterson had to leave his immaculate cocoon in order to collect samples from a very dirty world. He reasoned that by drilling down and extracting a deep vertical core from glacial ice in Antarctica, one in principle should be able to detect changing isotopic ratios of lead in the layers of snow laid down successively over long periods of time and frozen in place. He hypothesised that the ratio of new lead to old lead would increase as one experimentally moved up toward the surface, toward the era of automobility. Those isotopic measurements would be performed back in the ultra-clean lab in Pasadena – but how could Patterson prevent contamination of ice from way down below by modern lead that was all around him as he dug?

Patterson devised a mobile truth-spot – in effect, reproducing the immaculate conditions of his California lab on the ice shelf in Antarctica. He created a temporary and portable ultra-clean lab out in the field where specimens of nature could be gathered under more-or-less the same controlled circumstances. The risk of contamination was everywhere – lead was on the electric chainsaws that Patterson used to slice into the walls of an inclined ice tunnel and in the winches used to haul up the chiselled ice blocks. It was also present in the polyethylene bags and 10-gallon drums used for shipping the samples of melted ice back to Caltech. The US Army engineers at Byrd Station who ran the collection site in western Antarctica had the nasty habit of spitting and urinating just about anywhere in that cold empty wilderness – and, of course, their mucus and excrement was full of lead. All equipment had to be dipped in acid, and the samples tightly sealed up before shipping out.

Patterson’s hard-won data supported his hypothesis: looking back in time through several centuries of ice, the proportion of lead from industrial sources increased as one approached the present day. In the 1960s, he took those findings (and more) to the US Congress, where he persuaded senators that lead measurements done anywhere other than in an ultra-clean lab – ie, his immobile one at Caltech or the mobile lab in Antarctica – were contaminated and unreliable. The laboratory itself turned out to be the lynchpin of Patterson’s persuasive efforts. In the US, the use of tetraethyl lead as a gasoline additive was finally banned by law in the 1980s.

Just outside the imposing modern courthouse in the city of Yibin in Gong County, in China’s south-west, four official-looking people – two men and two women, wearing dark-blue suits, white shirts and black ties – load folding tables and plastic stools into the back of a white microvan. Each wears a lapel pin showing the emblem of the People’s Court, which also appears above the main entrance to the court building. The Yibin courthouse was opened several years earlier, in 2003, as part of a nationwide effort to advance the rule of law in China by building new courtrooms in which to conduct public trials.

The van is loaded up. Three judges, a clerk, their portable furniture and placards displaying the Chinese characters for ‘plaintiff’ and ‘defendant’, leave Yibin and drive for an hour into the countryside, arriving at the village of Longjia. The UK filmmakers Maggie Still and Bruno Sorrentino recorded these events as part of a five-segment TV series about changes in China’s judicial system, which aired in the US in 2009 on the PBS programme Wide Angle.

All was not well in Longjia. Mr Li Yaoquan, a farmer who has lived in the village his entire life, has an ongoing disagreement with his neighbour, Ms Li Caiqun (no relation). Her new house shades Mr Li’s property. Their dispute escalated when Mr Li discovered one day that a number of his bamboo, banana and tea trees had been destroyed or damaged by fire – and he suspected that Ms Li was responsible. Efforts to resolve the matter locally through traditional mediation by the village head, Zhang Chengyu, had failed: ‘They really don’t like each other,’ Mr Zhang said.

Mr Li, like most residents of the village, had never been in a brick-and-mortar courtroom. But on that day, the court would come to him, with the white microvan (with ‘court’ in big blue characters on its door) pulling into the village. The judicial officials from Yibin unload their furniture and signs, and set up a mobile courtroom outside in an open but muddy spot that has a clear view of the damaged trees. Ducks and geese waddle through at their pleasure. Great care is taken to set up the tables and stools in a way that mimics their arrangement in a permanent courtroom. The judges and clerk sit in a row on blue plastic stools behind two tables, and hanging from the front of the tables is a big sign with the official red emblem of the People’s Republic of China, reading: ‘Mobile Tribunal of the Gong County People’s Court’.

Mr Li sits to the right of the judges, and Ms Li to their left, with her legal aide. In front of the litigants, on low blue plastic stools, are folded cardboard signs spelling out the specific legal role of each party: ‘plaintiff’ and ‘defendant’. Opposite from the judges’ table is space for the audience, and indeed it seems as though everybody in Longjia has turned out to watch the proceedings – including children and three women busy at their knitting. Mr Zhang, the village head, sits with a few others on a rude wooden bench moved here to the ‘gallery’ from elsewhere in the village.

With the makeshift courtroom now in place, Mr Li pleads his case. He points to the nearby slope where visibly burned trees become (for him, at least) compelling evidence of Ms Li’s guilt. He requests that the court ask the defendant to give him the equivalent of $520 to cover property damages, later dropping his request to $130. The judges are not convinced, or at least feign doubt, that Ms Li set fire with the intent to destroy Mr Li’s trees. During a break in the formal proceedings, the judges have sidebar conversations with each litigant in hopes of reaching a settlement, and one judge is heard telling Ms Li: ‘Just you be more careful next time you burn your weeds!’

The courtroom is broken down, ready to visit another remote village for a chance at justice

The court reconvenes, and all parties take their designated seats. The judges award Mr Li only $52 in compensation for his loss, and Ms Li immediately pulls the cash from her pocket and sets it on the judges’ table. Mr Li laboriously writes out a receipt, confessing that: ‘This is the first time I’ve had to write anything in 50 years.’ The chief judge announces that ‘good neighbours are more important than distant relatives’, and with that, the case is closed. The courtroom is broken down. Tables and stools are loaded back into the white van, ready for visiting another remote village where a chance for justice awaits.

The muddy temporary truth-spot assembled in Longjia, patrolled by ducks and geese, has restored community peace. Both parties seem content with the outcome, and accept the legitimacy of the process. Mr Li says that the judges ‘seemed really concerned and took really good care of the case’. Perhaps more consequential than either the verdict or the amount awarded is the villagers’ experience with an emerging Chinese legal system. Thirty years before, coming out of the Cultural Revolution, Chinese courts were just beginning to rouse from a two-decade slumber. Now, even in a remote village where no permanent court facilities exist, residents come to see that state law can be an effective tool for them to pursue remediation and justice before impartial – and sometimes itinerant – judges.

Portable altar, temporary lab-in-the-field, mobile court – each travelling truth-spot did its job to make people believe. Certain shared understandings acquired legitimacy as they emerged from ordinary places provisionally made special by the momentary unpacking of transformative stuff – Aztecs get aligned with the tenets of Catholic missionaries; scientific data from Antarctic ice convince US Congress to ban lead from gasoline; disputatious neighbours in a remote Chinese village reach an agreeable legal settlement. But lasting churches still get built, and so do brick-and-mortar laboratories and courthouses – often at great expense, and in locations strategically chosen to accentuate their persuasive powers.

We ought not to forget possibly the most important lesson from the Oracle at Delphi. After a thousand years as the mythic centre of the universe, a spot where mortals once connected with the gods and received credible prophecies about the future, the sanctuary at Delphi vanished from the side of Mt Parnassus. Starting after the fourth century AD, stones previously used to hold up sacred temples and treasuries were refashioned by local residents to build mundane houses and shops in a place they called Kastri – largely oblivious to the oracular history of the site. Only in the 19th century did archaeologists rediscover the location where the legendary activities of Delphi had taken place. No truth-spot is forever (but some are more fleeting than others).