When I went home for the 2007 holidays, in my last year of college, my mom’s new favorite phrase was ‘mobile social networking’. It was a big thing in Asia and Africa, she told me, in the throes of writing a several-hundred-page market report.

What is it supposed to be? I asked, getting the milk out of the fridge and making myself some muesli.

Well, she said, you joined a social network on your phone, and then you could express opinions about things. You could send something to your friends, and they would say if they liked it or they didn’t like it — on their phones.

That sounds really stupid, I said.

But, as I don’t think I need to stress, the idea turned out to have legs. In my defence, the first iPhone was still six months away. And though I was one of the first few million users of Facebook, the ‘Like’ button wouldn’t come along for years.

The future arrived much earlier in our house than anywhere else because my mother is an emerging technologies consultant. Her career has included stints as a circus horse groom, a tropical agronomist in Mauritania, and a desktop publisher. But for most of my life she has lived by her unusual ability to see beyond the glitchy demos of new tech to the faint outlines of another reality, just over the horizon. She takes these trembling hatchlings of ideas by the elbow, murmurs reassurances, and runs as fast as she can into the unknown.

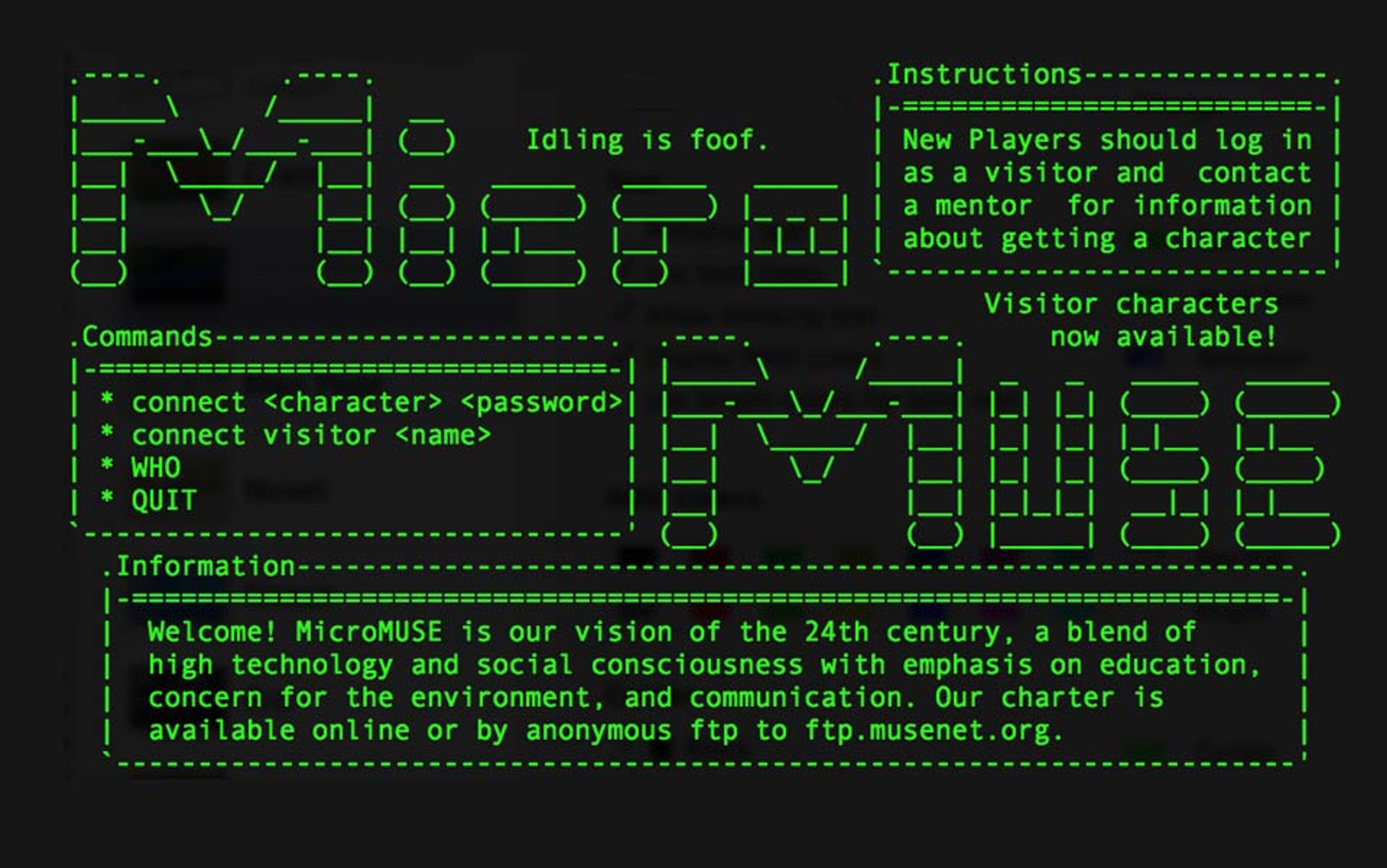

When the web and I were both young, in the mid-1990s (with 10,000 pages and a third-grade education to our respective names), video conferencing was my mom’s thing. We had our county’s first T1 fibre-optic line thanks to her, and I grew up in a house full of webcams, shuddering and starting with pictures of strangers in Hong Kong, New York and the Netherlands, to whom I’d have to wave when I got home from school. Later on, when I bought a webcam for the first time, I could not believe you had to pay for them — I thought of them as a readily available natural resource, spilling out from cardboard boxes under beds.

It’s not a particularly comfortable place to be, that knife’s edge between the next big thing and a truly embarrassing evolutionary dead-end

My mother worked with companies who wanted to develop software and hardware for video conferencing, and she wrote reports about the state of the market, which, at that point, was a slender stream of early adopters. Internet connections were so slight, and the hardware so bulky and expensive, that it was slow going — tech start-ups launched with fanfare and sank within months, unable to stay afloat on the ethereal promise of everyone, everywhere, seeing each other talk. The promise, too, of never having to travel for business was not as appealing as the start-ups thought it would be.

But my mom is a futurist, that peculiar subclass of optimists who believe they can see the day after tomorrow coming. In the 1990s, she ordered pens customised with her consultancy name and the slogan: ‘Remember when we could only hear each other?’ Years later, when an unopened box of them surfaced in her office, she laughed and laughed. It would be another several years before Skype with video brought the rest of the world up to speed with her pens.

And by that point, she’d moved on.

It’s not always a particularly comfortable place to be, that knife’s edge between the next big thing and a truly embarrassing evolutionary dead-end. We were constantly wading through early models of doomed technology, and we dressed in, wrote with, and drank out of the detritus of wrecked start-ups. My dad’s favorite polo shirt memorialised a company that had not existed for at least a decade, and for toys we had stress balls and small plastic tops from telecom tradeshows. We had a massive TV-like device mounted with a swiveling webcam before which, at my mother’s behest, I played the clarinet for children gathered in a classroom thousands of miles away. I have not seen one of those in anyone’s living room lately.

In 2004, the year I went to college, one of Forbes’ top tech trends was that consumers were beginning to buy more laptops than desktops. I took a laptop with me, of course — we’d had one or two around the house for years, and I think we bought three more that summer — but I also took a video phone. It was a silvery chunk of plastic with a handset on a cord, a dialpad, and a four-inch screen on a hinge on which I could see my family every week or so. It was the way of the future, and my mom wrote an article about using it to keep up family ties across long distances. The next year, when my sister went away to college, she did not take one. That fateful Skype release had occurred in the intervening 12 months, and the days of dedicated hardware were through.

Strangely enough, after the video revolution came, it no longer seemed to interest my mom. I had not fully grasped it until that point, but her interest was in premature things — full of potential, hampered by bizarre deformities, in need of her talents. Unlike almost every consumer of technology, for her, and for a few others like her, the sleek final product held much less interest, except as a sign that their instincts had been correct.

The bugs, in other words, were more than just bugs. They were opportunities. And without people who have this affinity for the half-formed, we might not get anywhere much at all.

Some years later, as an intern at Popular Science magazine, I was doing research for a retrospective that highlighted the products that had stood the test of time and Googling a quarter century’s worth of inventions featured in the Best of What’s New awards. In an image search for one of the products — I cannot now remember which, and don’t have a record of it, but it must have been a monitor-mounted webcam — I found a small photograph of my mother, in her office in a house we’d long since moved out of. The photo showed her head and shoulders off-center, against a white wall. She was wearing a peach turtleneck and a loose bun, and she stared into the lens of this now-forgotten device with an attentive expression, as though looking for a sign of things to come.

I’ve never thought of my profession as being at all connected to my mother’s. It’s easy to forget that they might seem to be related. Which makes these spooky moments, when I stumble across her signal in the noise, all the more eerie.

My career as a writer about science, and sometimes technology, arose from a particular moment in a college class in cell biology. Late in the semester, we watched a silent movie of a cell dividing. The frenetic activity within the cell paused, and the twinned chromosomes assembled into a straight line. Then they began to pull apart gently, tugged by invisible threads into halves, identical, but destined for existences in separate spheres. I wanted to get closer to that ethereal beauty, to help people understand more about what was happening there — a process still so mysterious, even after decades of research, that our professor was forever coming into class with updates to the textbook. Together, my career and my upbringing have given me something important: a taste for the beautiful and the patience to wait it out, if not the desire to midwife it myself.

These days, the devices strewn around my parents’ apartment are augmented-reality glasses and headsets. The dinner table talk has been about waypoints and layers and standards for content. Mom’s latest projects include turning a city’s publicly available data into an app that lets people see the transit system or sewer pipes projected over the reality before them. She’s been talking to hang-gliders and hot-air-balloonists about whether they would like to see the wind unfurling across the sky ahead. And years before Google Glass was even on the horizon, my mom had me try out a pair of glasses that were to provide an immersive movie theatre experience. (The earbuds mounted on the frames, I regret to say, had not been designed with young women in mind.)

Sometimes I think I could sell my services to these people with the tagline: ‘I come from the future’

But while there have been some industry successes — mainly in the form of games, and the Yelp app, a big standout — augmented reality is going through an awkward adolescent phase. It’s good for PR stunts, like the billboard that went up in Stockholm a couple of years ago and let passersby win McDonald’s food by playing ping-pong with their smartphones. Or the display in Korean subway stations that lets people ‘shop’ for groceries by snapping pictures of QR codes. But will there ever be, as my mom thinks, a secret digital world underlying the real one? A Metaverse visible through your phone, and soon, she hopes, through glasses? Several months ago I went to a release party for a phone loaded with augmented reality features, and the demo was a groan-inducing animation. We’re not there yet.

Sometimes I think I could sell my services to these people with the tagline: ‘I come from the future.’ I don’t have all the hallmarks of a standard techie: my cell phone lives peacefully unconnected to the internet, and I belong to relatively few social networks, but I am from a bubble in time, a place where these things have always existed. I can tell you what users are going to want, because I have seen, over the course of my short life, so many things fail, and so many unlikely things succeed.

That said, I would never want to be too far away from those who live and work perpetually in the vanguard, who have chosen that risky, Schrödinger’s Cat-like existence. Even after growing up with my mother and the remains of a hundred half-baked ideas, such people’s willingness to ride the wave, their foolhardiness and their bravery, still provokes awe in me. It’s not a thing I can profess to understand beyond a basic respect for their guts and their kind of crazy hope that the future will be weird. But that’s something I can get behind.