A curious thing happened when my grandfather died, the sort of thing that seems more and more curious as the years pass, investing itself with significance. At the time I was living in New York, and since this was the middle of the last decade, I was always only a phone call away from my family in India. What we weren’t able to do, though, was text each other; I had been told by my mobile provider that the network systems in the two countries were misaligned in some key manner. This had sounded too vague — too 20th-century — to be truly credible, so my sister and I attempted a number of times to exchange texts, out of habit and idle hope, before admitting that we were wholly defeated.

Then in March 2007, when the old man passed on after a long illness, my sister took another crack at it. She couldn’t call right at that moment but she wanted to let me know, so she fired off a text, expecting it, as always, to sink into the void. On this occasion, however, the iron laws of telecommunications unbent themselves and the message made it through, into my phone, waking me up in the dead of night. Just this once. Even five seconds later, when I tried to reply, the channel had snapped shut, and it never opened up again.

A final flare of mystery from a mysterious man, I thought. He was 94 when he died, and he and my grandmother had stayed with us, whenever possible, for much of my life; my father was their eldest son. I should have known him far better than I do, I realised upon his death. I grew up around him, accustomed to his presence at home: to his shirtless torso, brown as a violin; to the angle at which he arced his leanness over the newspaper; to the ellipses of sunlight in which he liked to sit, in feline habit, next to the window; to the low bicker of his voice in prayer; to his twitchy handwriting; and, in his final years, to the degree of cloudiness in his fast-fading eyes. These were the precise aspects of a precise man.

He was, by no means, shy or retiring, and he involved himself with great energy in my early boyhood, such that my memories of those years can run together like a heavy-handed pastiche of grandfather-grandson montages. Here he is, dropping me off on his bicycle at the stop for my school bus. Here he is, sitting with me, watching the cricketer Patrick Patterson bowl on our black-and-white television. Here he is, telling me stories, spun mostly out of his capacious memory for Hindu myth and dramatised to eye-popping effect. Here he is, teaching me arithmetic, his mind as sharp as soda. He brooked no dullness, even from a boy in his very first throes of long division.

‘The answer is 12,’ I’d venture, for instance.

‘That’s the quotient,’ he’d snap. ‘You’ve forgotten about the remainder altogether.’ He didn’t rap me on my knuckles with a ruler, as he had done with his own children. But the rebuke of scorn was almost as stinging.

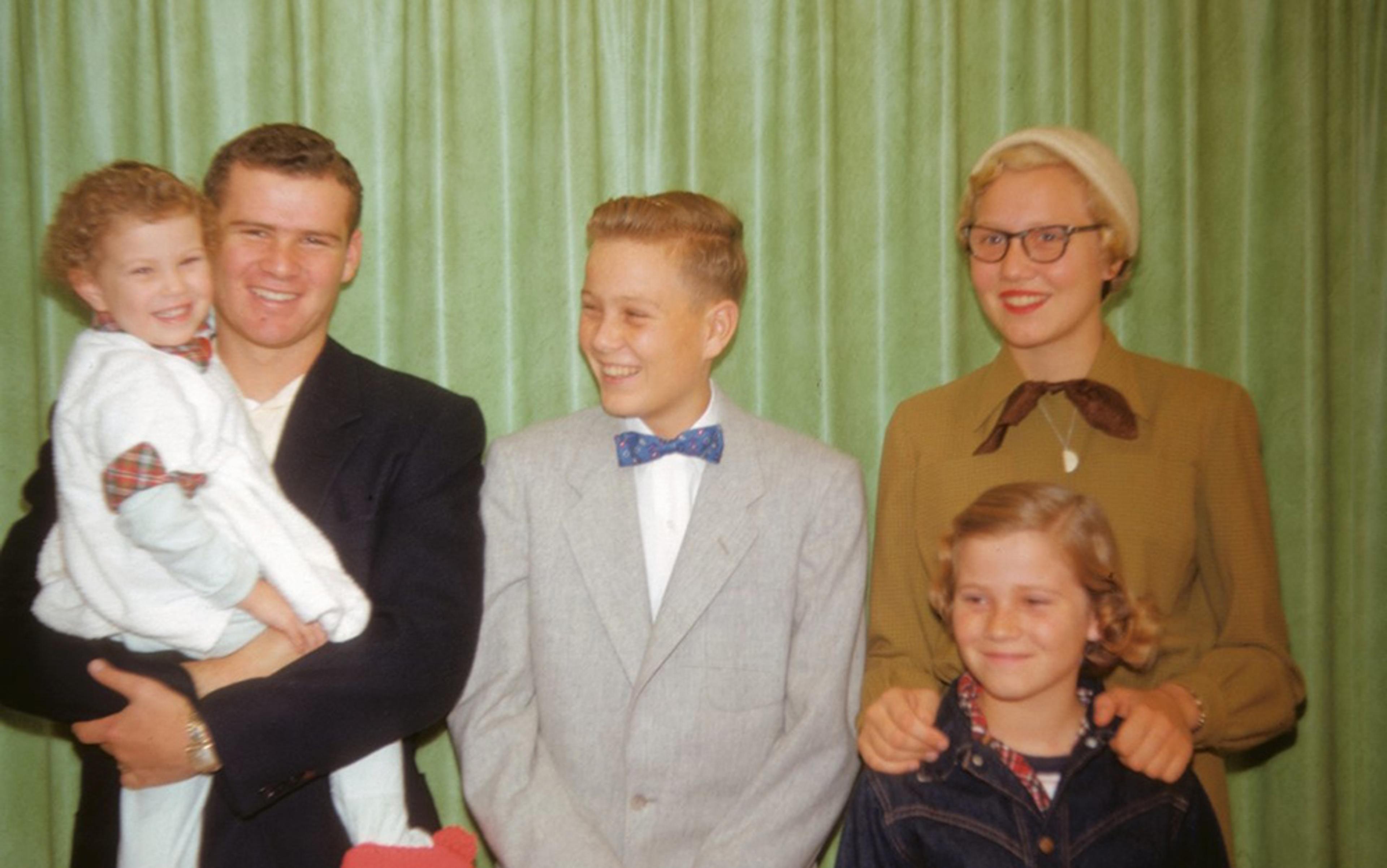

Once, when he had to call upon the president of India in connection with a temple trust that he ran, he took me with him. An eight-year-old boy, meeting the president — imagine the intoxication! I still have a photograph from that encounter, taken in President Ramaswamy Venkataraman’s study, the two old men standing long and solemn on either side of me. My grandfather looks the way I have always known him to look: the nimbus of white hair aglow with soft light, the nose hooked like the beak of a bird of prey, the skin on his hands wrinkled. I am wearing a cream-coloured T-shirt with brown stripes, and my face is occupied entirely by overlarge spectacles and a grin of delirious happiness.

I’ve grown up to be very similar to him, I’m sometimes told by my father’s sister, and every time she observes another trait that I’ve inherited from him, I add it silently to the running list in my head. I started the list myself when I was a boy, as soon as I turned old enough and sensible enough to observe both my grandfather and myself. Some of the items on this roster appear trivial: unhealthy skin, for instance, or being restless readers, or being particular about our meals, or being particular really about the way most things are done. But there were also deeper kinships: an impatience with fools; a meticulous industry; an unending love of language; a certain self-sufficiency that makes it difficult to feel lonely, but that renders a rare spell of loneliness all the more fearsome and crippling. My grandfather was all edges and sharp corners. I came to think — to worry — that we were cast from the same essential mould, and I have spent years filing myself down into a less severe version of him.

Given all this, I now wonder, why did I fail to learn more about him? It is true that, for all the diligence my family has expended on passing down the rituals of our religion, it has never been as attentive to personal histories; I know absolutely nothing about my eight great-grandparents except for the name of one of them. Even so, my grandfather always felt like a special case — less a real person than a character pulled out of a fable, his abilities and his flaws both immensely larger than life, and his past obscured as much by my own ignorance as by the half-truths and legends that swirl around him.

The human mind requires coherence, craves it. Out of the most motley assortment of disjointed facts and malformed rumours, we compulsively build ourselves a narrative, and we can cling to that narrative so obstinately that it begins to stand in for reality. I hold in my head a sketchy biography of my grandfather, populated by the stories I’ve been told, the conjectures I’ve made, and the resounding uncertainties that still hover over his life.

He was born a century ago in the small Tamil village of Kattalai, deep in the heart of south India — a village that, it dawns upon me even as I write this, I have been remiss in never visiting. For many years, I was under the impression that he ran away from home at the age of 14; as a boy on a subsistence diet of adventure novels, I used to regard this as the sole feat of derring-do in my family history. It turns out that he left only when he was 18, after he had completed a degree in mathematics. Still, he did then run away in the classically exciting sense of the term, severing all contact with his family, taking to the road as a Hindu mendicant, living on charity and his wits. ‘It must have been,’ my father once said to me, ‘the life of a vagabond.’

He also displayed a new-found ability to quote the Bard. Did he take three months off to plough through a copy of The Riverside Shakespeare?

He was speculating. These were my grandfather’s lost years, never recounted or explained, closed off to us until the day he died. Once, I believe, he let it slip that he had headed up India’s eastern coast, towards Calcutta, but this fine splinter of information apart, we have nothing. We don’t know how long he was away, or how he travelled, or where he stayed, or whom he met, or why he ended this spiritual walkabout. He never returned to live in Kattalai; after this prolonged silence, his family heard from him only when he came back south to live in the city of Madras, where he was acting with — and also serving as the cashier of — a musical theatre troupe. This was the first sign of a new man. In Kattalai, my grandfather had not trained in music, nor had he shown any keenness for the stage — and yet here he was, singing and declaiming in mythological dramas alongside the stalwarts of his time.

‘Did you never press him about what he did in that period when he was away?’ I asked my father recently.

‘He never encouraged such questions,’ my father replied. I sensed some regret lacing his voice. ‘And he never wanted to talk about it of his own accord.’

Reconstructing the details of my grandfather’s wanderings can feel like a thought experiment. That span of time changed him, but since we know only the man who emerged out of the other end, the most we can do is make forensic guesses about what happened during those years. He had acquired, for example, a profound familiarity with the Upanishads, a canon of Hindu philosophical texts, and he had also studied the first rudiments of a system of faith-healing that he practised throughout his life. Had he apprenticed under some teacher of philosophy, or under a Hindu shaman? He also displayed a new-found ability to quote the Bard, accurately and at length, the lines ringing with his nasal twang. Did he take three months off to plough through a copy of The Riverside Shakespeare? He had learnt to cook, too, with uncommon proficiency for a man of his time. Had he needed this skill during his perambulations?

Even after he returned, my grandfather continued to move in enigmatic ways. He shifted, on an inscrutable impulse, to Delhi, where he taught mathematics at a school for a while; his students apparently performed so well in their exams that they hoisted him on their shoulders and paraded him around the school. The father of one of his pupils, a civil servant, was impressed by my grandfather, securing for him a position in the coal ministry. He was nominally employed by the government for the rest of his working life, but as far as I can see, he really seems to have passed those days turning himself into a sort of polymath. My grandfather blazed with knowledge. His Sanskrit grew so fluent that he could compose lengthy verses of prayer. He gave public performances as a storyteller, in which he would first recite sing-song snatches of the Hindu epics and then, out of these, extrude a moral commentary. He soaked up the ancient architectural principles of temple design. One of the temples he had helped to plan lies a few kilometres west of where I now live in Delhi; every time I drive past this temple, I gaze up at it, sitting proud and solitary upon its hillock of rock.

Nobody in the family is even roughly aware of how my grandfather learnt all that he learnt, and a particular opacity surrounds the expertise for which he was best known. From somewhere — from many sources, probably — he had gathered up prayers and incantations that were supposed to relieve people of their illnesses. Sitting opposite his ‘patient’, he would mutter, for minutes on end, the prayer to purge that specific ailment. He bristled with concentration during these sessions, his papery lips aflutter.

On occasion, setting aside my scepticism, I submitted myself to these disconcerting consultations. A bubble of silence would drop around us, as if he had managed to shut the universe away for those 10 minutes. I’d bend my ears, trying to pick up some of the words that he was whispering under his breath, but invariably I would hear nothing. Then I’d look at him looking at me — or through me, into some hidden beyond. The air around him crackled; his aura was so strong that invariably, towards the end of each of these sessions, ripples of doubt would run through my mind. Maybe I was wrong, I would think, maybe these old prayers had a real potency to them. And then I would look with fresh interest at the man muttering the prayers, who believed so implicitly in their worth.

I don’t recall being healed by him of anything, but many of his other cures were reputed to work at miraculous speed, and the sick streamed steadily through the doors of his house in Delhi. Within the city’s community of Tamil Hindus, his name can still draw quick recognition. ‘I knew him so well!’ I’ve heard people exclaim, upon learning that he was my grandfather. I’m not sure you did, I have always wanted to respond. We aren’t certain we knew him well at all.

I was born when my grandfather was 68, already in the late afternoon of his existence. We see our parents ageing before our eyes, but we regard our grandparents as such oaks, their mortality not once entering our thoughts because they have always, to us, been old. By the time I began to realise the urgency of learning about him, he was gone. I never had the chance — or, to be perfectly honest, I had the chance but never took it — of asking him straight out about his life. I should have asked him about what drove him, what angered him or misled him, how he handled his inner conflicts, what lessons he had derived from the mistakes he had made. If we were as similar in temperament as we were made out to be, I might have benefited from his hindsight and his advice. But I never put any of these questions to him.

Have there ever been generation gaps as yawning as the one between a grandfather born in the 1910s and a grandson born in the 1980s? We were separated by India’s most momentous decades. When he was a baby, the prospect of independence from the British was still only a glimmer on the horizon; by the time he first held me in his arms, he had already witnessed two world wars, the rousing energy of the Indian freedom movement, wars with China and Pakistan, and men on the moon. His life was longer than the Soviet Union’s. Until late in his youth, he had never seen a telephone or perhaps even a radio, but he lived long enough to speak on a cell phone. The human race created its most extreme horrors and wonders during these decades, and they unfolded before him in real time; I learnt about most of them out of history books.

As the country transformed, it contrived to leave him behind. This is often the case, of course. In the new India, there was progressively less space for a man from a priestly caste whose life revolved around his faith. A flair for the Upanishads will not get you very far now. People seek — quite rightly, I hurry to add — to be cured of their ailments by science instead of prayer. Nobody pays much attention to the astrological charts that my grandfather used to pore over, trying to siphon fates and fortunes out of the positions of the planets. None of these changes are calamitous in themselves, and yet a dim sadness tugs at me when I think about a man’s way of life made redundant during his own time.

Under my uncaring stewardship, a certain continuity has snapped, and a vast body of inherited knowledge has suddenly and irreversibly decayed

There is some complicated guilt here too, lurking in the corner but unavoidable. I have felt as if I am personally responsible for rupturing traditions that run back many generations and that are still alive, to some extent, in the person of my father. I cannot read or write Sanskrit, my stock of Hindu hymns is meagre, and I am unable to deliver the liturgy for even a single ceremony of worship. This can only partly be blamed on my education, which was styled so strongly after Western curricula that I can conjugate French verbs but not Sanskrit ones. Mostly, it is my own fault — my own deficit of interest, my own coolness towards faith and religion.

Thus, under my uncaring stewardship, a certain continuity has snapped, and a vast body of inherited knowledge has suddenly and irreversibly decayed. This was the price of progress and modernity, I reasoned at first. Only later did I come to think that the loss of cultural knowledge of any kind is always a tragedy. And yet, contained snugly within these same traditions were elements of blind superstition, of Hinduism’s invidious caste system, and of rigid and impractical ritual. These practices, born of less enlightened times, are unquestionably better off dead. So what, then, is the proper amount of remorse for me to feel here?

I struggle still with this slippery question, just as I struggled to grasp the details of my grandfather’s life. For all the mystery in which he cloaked himself, I think now that I also failed simply to be curious enough about him. Perhaps it suited me, the grandson, to consign him to oblivion: the world had changed so much since his time, I must have reckoned subconsciously in my boyhood, that there was no need to understand his era, and therefore no need to understand him. I was committing, of course, the arch sin of the historically ignorant. Only after I grew older, when my life had built its own slim back-story, did I begin to see how vitally the present is inflected by the past, and how much of my grandfather lived on in me. This is how we negotiate our past: we fumble with it, discard it, pick it up again, trying to see what new things it can tell us about ourselves, always hoping that it is never too late to learn.