Britons have been on the move for centuries. In the 17th century, they began to cross the seas and people other continents, seeking both economic opportunities and religious independence. Nonconformist Protestants from East Anglia and the younger sons of the West Country departed to establish colonies in New England and Virginia. Later, following England’s union with Scotland in 1707, southern absentee landowners took control of land along the Anglo-Scottish border. Emigrants driven from the borderlands pushed deeper into the North American continent, including the Appalachian mountains, the American ‘back country’. En route, they often passed first through northern Irish cities.

Meanwhile, new peoples were coming from Europe to Britain. London, a polyglot city, was already home to traders and merchant bankers from across the continent. French Protestants, called Huguenots, fled religious persecution in their home country to settle in London as ‘Strangers’. Practising their trades, they disrupted the economic livelihoods of native, English-born artisans. In short, it was a time of movement of peoples, currents of them, coming and going from near and far.

Rising and contested English political power brought more tumult. The English government’s colonial occupation of Roman Catholic Ireland also continued apace. Through the 16th and 17th centuries, though royal and Parliamentary administrations might have opposed one another, they agreed on the imperative of Irish occupation. In the early 16th century, Henry VIII extended the English legal administration into Wales. There, an Anglicising Welsh gentry taught its children to speak and read English while also intermarrying with the English. Welsh survived, for the time being, in the churches and as spoken among the ‘vulgar’.

During the 1640s and 1650s, Parliamentary and Royalist forces marched up and down Britain and Ireland. Many of these soldiers had never travelled farther from home than their local market towns. When the parliamentary leader Oliver Cromwell triumphed, executed the King, and ensconced himself in London as Lord Protector, many Royalists fled (temporarily) to the continent.

The combination of movement, migration, warfare and flexing English power brought on an identity crisis. Who were the peoples on this great island and who were they becoming? In the modern sense of the term, they were not ‘Britons’. ‘Britons’ referred to the pre-Roman inhabitants of Britain and their latter-day descendants, the Welsh. This group might be expanded to include the Scottish and the Irish. The English counted the Britons among their ancestors, but did not themselves identify as British. Everyone – the English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish – saw their homeland as an independent kingdom. Beginning in 1603, James I and his son Charles I attempted to rule over England, Scotland and Ireland as one head over three bodies, only to see their union break down into civil war and rebellion.

An emerging empire offered the beginnings of a possible shared identity. When were the English, Scots, Welsh, Cornish and even some of the Irish most likely to recognise one another as fellow Britons? Never so much as when they together colonised other lands and peoples. Some Britons sought a deeper ‘Britishness’, something from within to transcend local and ethnic divisions and bind them, make them a people.

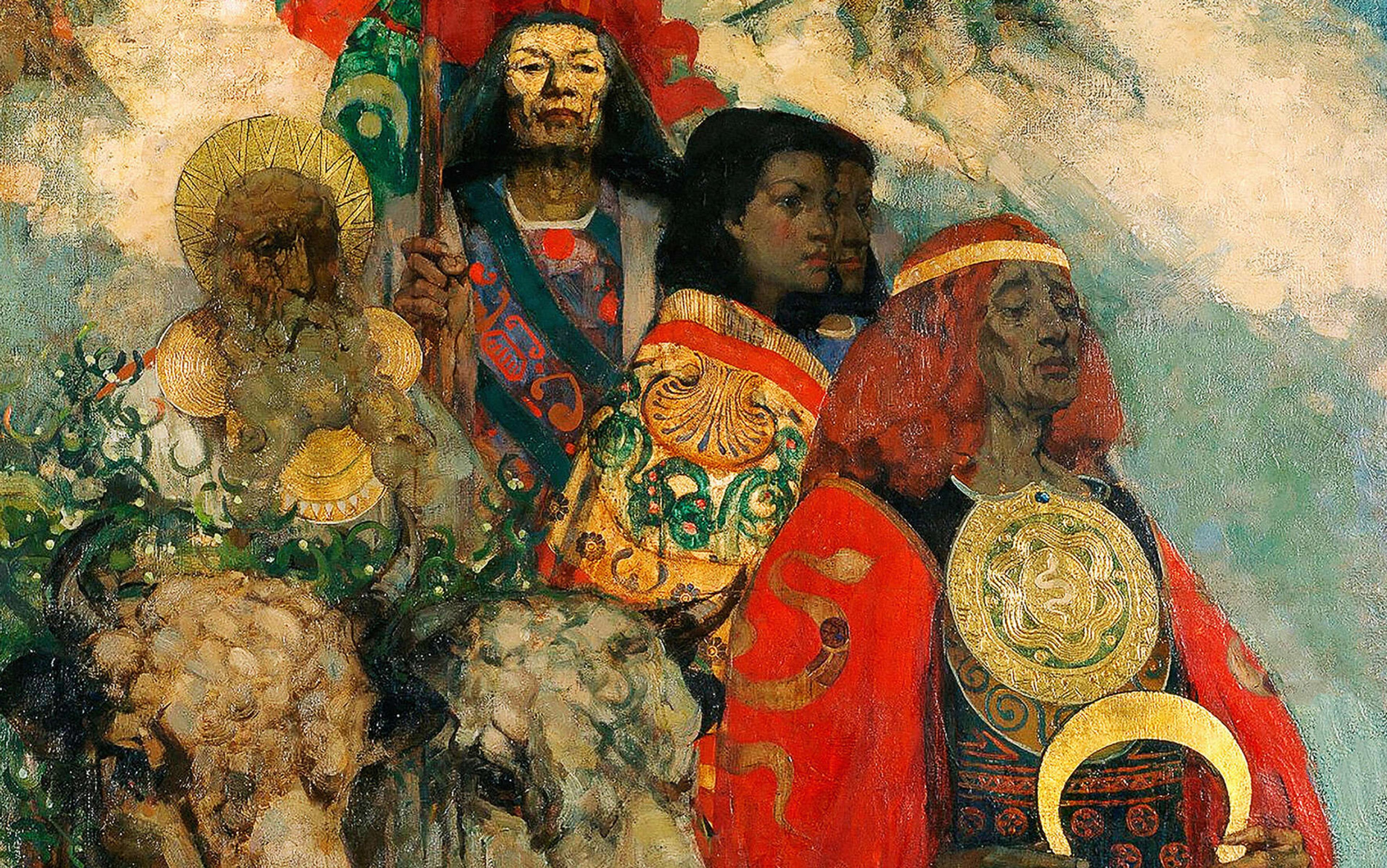

A loose cadre of gentlemen antiquaries and naturalists took the initiative. Seeking to re-ground Britain, and British identity, in a shared human and natural history, they fanned out across the land. By excavating, surveying and drawing relics, ruins and monasteries, these antiquaries helped to create a history of Britain. They recovered smaller artefacts, too. The coins, weapons, jewellery and household objects collected by the gentlemen antiquaries contributed to Britain’s growing material history.

These antiquaries paid special attention to the United Kingdom’s languages, which philologists organised geographically. With the goal of understanding the history of human settlement in the British Isles and Ireland, they mapped the distributions of placenames, regional vocabularies and pronunciations. Extending their researches into the natural world and deep history, naturalists collected and categorised plants, animals and fossils. They searched for a distinctively British natural landscape. Their pioneering systematic and comparative approach helped to build the foundation for modern archaeology and natural history. From architecture to sculpture, from language to plant and animal species, there was little that escaped their efforts to collect and classify a deep, shared history of Britain.

They explicitly understood their efforts as key to building a British political identity. When in 1660, Charles II was restored to the British throne, the virtuoso naturalist Joshua Childrey took the occasion to clarify the link between geography and people. In his Britannia Baconica, a natural history of England, Scotland and Wales, Childrey declared that the book was not a ‘Telescope, but a Mirror’. He was in other words not finding things, he was showing the people themselves. Or, in his exact words, Britannia Baconica was ‘not about to put a delightful cheat upon you with objects at a great distance’ but was simply a book that ‘shews you your selves’. Britons were the land; the land was Britons. Regional, ethnic, and religious differences faded in light of this underlying truth, or were meant to. The Restoration of Charles II, Childrey assured readers, promised that their deep shared history would triumph over their differences.

How was the gentlemen naturalists’ vision formed? Would it hold together?

In the summer of 1699, Edward Lhuyd stooped down low and crept into a barrow (an ancient burial site). An antiquary and natural historian, Lhuyd was just outside the Irish town of Drogheda, along the River Boyne, when he stopped to explore the barrow. He crawled across the carved stone lintel and entered a long, narrow passageway. He stood as the ceiling rose above him. His candle guttered, sending flickers of light into the shadow. The rude, uncarved stones that held up the cave were rougher, he thought, than those at Stonehenge. They called to mind the ancient standing stones at Avebury in England. Chambers branched out to his left and right. Peering into them, he saw broad, shallow stone basins, ready to catch holy water, or perhaps blood from a sacrifice. The flagstone across the entry to the cave, as well as the pillars around the basins, were carved with spiral figures, like snakes ‘without distinction of Head and Tail’. Loose stones and elk bones littered the earthen floor.

Lhuyd guessed at the barrow’s age. A gold coin bearing the head of the fourth-century Roman Emperor Valentinian had been found in the turf above. The coin suggested the barrow was ‘ancienter than any invasion of the Ostmans’ (Vikings) who occupied early medieval eastern Ireland. The resemblances between the stone carvings and monuments in England pushed the barrow’s origins into the pre-Roman era. ‘It was,’ Lhuyd wrote, ‘some Place of Sacrifice or Burial of the Ancient Irish.’

Lhuyd linked the barrow at Drogheda to stone circles at Stonehenge and Avebury. All three, he suggested, were products of an ancient common culture, one that preceded the Vikings and the Romans, and of course the Anglo-Saxons. Lhuyd’s judgment challenged his contemporaries, some of whom still called Stonehenge ‘the Giants’ Dance’. According to a popular myth, Irish giants and British wizards had whizzed the stones that made up Stonehenge from Africa to Ireland and then to Wiltshire. Modern observers – the architect Inigo Jones, for example – credited the monument to the Romans. Jones and most others believed that Ancient Britons were too primitive a people to have accomplished it. The physician Walter Charleton argued it was Viking-built.

each antiquary’s national allegiances shaped his version of Britain

In order to claim Stonehenge for the Britons, Lhuyd and his fellow antiquary John Aubrey surveyed and compared monuments across the British Isles. Aubrey made ‘the Stones give Evidence for themselves’. He taught himself the use of surveying instruments and showed that Jones, using shoddy measurements, had shoehorned Stonehenge into his concept of an ideal Roman temple. By drawing comparisons to Avebury, a stone circle so vast that it encompassed a village, Aubrey discovered a set of regularly spaced holes, now named ‘Aubrey holes’, in a circular perimeter around the monument. Aubrey established that these holes once held additional standing stones. Lhuyd and Aubrey disproved Charleton’s Viking theory, too. Stone circles existed in parts of Britain where the Vikings had never settled. Besides, wrote Aubrey and Lhuyd, pushing down the Vikings to help raise the Britons, the Danes were a band of ‘roving pirates’. They were not capable of any sophisticated architectural effort.

According to the antiquaries’ history of Britain, the national story was one of national union, conquest, colonisation and trade. Ironically, each antiquary’s national allegiances shaped his version of Britain. The publication in 1587 of William Camden’s Britannia, written in Latin, inaugurated efforts to unify England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland through geographical study. Camden was an Englishman. In the 1610 English translation of Britannia, dedicated to James I, the first British monarch to rule over Scotland and England together, he praised the Scots, respectfully apologising that his coverage of Scotland was not as thorough as his coverage of England. Camden was sanguine about Scotland, but he denigrated as barbaric the ‘wild Irish’. According to Camden, the Irish had never known Roman civilisation, and thus were fit only to be conquered by the English. (Never mind that the Romans stopped short of entering Scotland, too.)

Classical heritage – Britain’s Roman history – mattered because it conferred status and authority. Into the 16th century, national lore identified the Britons as descendants of Brutus, a hero of the Trojan War. Medieval historians, inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid, invented Trojan origins for many European countries. Britain got Brutus, Aeneas’s great-grandson. But in the 17th century, the sway of Brutus and Britons’ supposedly Trojan origins was on the decline, victim to early modern antiquaries’ preference for well-attested ancient history over medieval invention.

Leaving Brutus behind, antiquaries sought scientific evidence linking modern Britain to classical civilisation. The English, in establishing what they felt to be their rightful dominance over Britain, placed themselves in a lineage with the Romans, whose territory had been roughly co‑extensive with modern England. Hence Jones’s identification of Stonehenge as a Roman temple, and Camden’s easy denigration of the Irish on the grounds that they had no connection with the Romans.

Other antiquaries sought out comparable classical lineages for the ancient British – and, by extension, their latter-day descendants. Aylett Sammes suggested that the Phoenicians, a sea-going Syrian people, colonised Britain. Sammes believed that a Phoenician colonisation would explain perceived similarities between Welsh, Hebrew and Greek. In this scenario, Phoenician and Hebrew were sisters, while Greek and Welsh were descendants of Phoenician. Lhuyd focused on what he saw as the great and suggestive relationship between Welsh and ancient Greek. He cast the ancient Greeks as the original ‘planters’, or colonisers of the British Isles.

Lhuyd’s vision emphasised solidarity between the peoples that the English marginalised

From 1697 to 1701, Lhuyd, with the company of two to three assistants, walked across Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and Brittany. As he travelled, he collected and copied medieval manuscripts, sketched ruins, plants, inscriptions, geological formations and fossils. He dove into coal mines and barrows. He planned a series of volumes outlining comparative Celtic natural history, antiquities and languages. His expeditions into the high and remote places of Britain took him out of touch with colleagues for months at a time. In Wales and Cornwall, people suspected he was a spy or tax collector. In Brittany, officials imprisoned and then expelled him. They imagined that his notebooks contained coded intelligence rather than lists of words in Welsh, Scots and Irish Gaelic, Cornish and Breton. In Scotland, he copied a set of useful Gaelic phrases into his notebook: ‘Did you see Parry today?’ His teenage assistant, David Parry, had a habit of wandering off.

Lhuyd, a Welshman, focused his research on relationships between the Celtic languages. He wanted to establish a linguistic foundation for a common history of the Celtic peoples. Though he wasn’t hostile to the English, he sought to raise the status of the British. Lhuyd’s vision subsumed England into the common Britain and emphasised solidarity between the peoples that the English marginalised. He culled language from living speech, as well as centuries-old manuscripts. Using a student dictionary compiled by his mentor, the botanist John Ray, he prepared a ‘core’ vocabulary list. ‘Core’ word lists are still an important tool in modern historical linguistics. They are words that, due to near-constant use by speakers, change more slowly than specialised vocabulary. Lhuyd transcribed these core words as they were spoken across the Celtic countries. Again, the point was to foreground the affinity of Britons.

Lhuyd moulded the Welsh spelling system into a standardised Celtic phonetic alphabet. His was one of several precursors to the standard International Phonetic Alphabet that linguists use today. He used this system to capture the sounds of native speakers of Welsh, Scots and Irish Gaelic, Cornish and Breton as they spoke the ‘core’ words. It was a way, before audio recording technologies, of studying how spoken language across a wide geographical area actually sounds. Given variations between the languages’ traditional spelling systems, Lhuyd’s standardised spelling made visible linguistic similarities and differences that previously had only been audible. Using his standardised phonetic alphabet, Lhuyd discovered systematic differences between the members of the Celtic language family and separated them into subgroups that are still recognised today. Historical linguists use such regular correspondences to establish the directionality of language change and historical relationships between languages and the people who spoke them. Lhuyd was one of the first to discover such relationships.

Travel, and the postal system, made possible the gentlemen antiquaries’ nation-building research projects. Natural historical and antiquarian research required an ‘active and large correspondence’ that spread across Britain. Through their correspondence, scholars compiled information and compared findings. The process of correspondence also strengthened the ties binding naturalists. Their own books offered their community as a model to the nation: making visible through citation their fraternal enterprise. They were slowly building a case for a broader, common British culture, rooted in history and the land.

In some cases, naturalists and antiquaries funded their work through their correspondents. Their highly illustrated books were expensive to produce. Booksellers, concerned with making a living, were reluctant to take such work on spec.

Lhuyd went one step further, funding his research – his five-year Celtic walking tour – via his correspondents. It was the 17th-century version of crowdfunding. He asked friends, friends of friends and relatives-of-friends to support his project by pledging annual amounts over five years. He shuttled stacks of printed proposals to his contacts, who distributed them further among their acquaintance. His correspondents assisted him in sealing the deal with written commitments, collecting signatures confirming donors’ annual pledge amounts. He applied social pressure, informing potential contributors how their most generous neighbours had pledged. Thus the funded research trip was born, in service of British nation-building.

Again working through his correspondents, Lhuyd distributed some 4,000 copies of a standardised natural historical and antiquarian questionnaire. It asked subscribers to help him to identify significant archaeological remains, manuscripts, fossils, coins, and plants and animals across Britain. Around 150 replies survive. One Pembrokeshire respondent noted that there had once been ‘a large British Manuscript History’ in the neighbourhood. Some 50 years earlier, however, Cromwellian ‘Round-Heads’ – religious independents – had destroyed it. Convinced that any piece of writing they did not understand must be ‘Popery’, these Protestants ‘adjudged all to the fire’. To Lhuyd, it was such ‘mistaken zeal’ that, mid-century, drove Britons to war with each other.

the antiquaries and naturalists also elevated folk culture, and folk knowledge

Naturalists and antiquaries also grounded Britain, and Britishness, in economic union. Though he didn’t necessarily agree with Sammes that the Phoenicians colonised Britain, Robert Sibbald, a Scottish antiquary, suggested that Britain’s very name came from the Phoenician word for ‘tin’, a commodity for which Britain was known since pre-Christian days. As he travelled the Celtic countries, Lhuyd alerted his correspondents to products and technologies that might find buyers or investors in England. He promoted, for example, a new machine for rolling sheet iron. It produced thin, strong sheets suitable for ‘Furnaces, Pots, Kettles, Sauce-Pans’, and other iron goods, and at a saving.

In Britannia Baconica, Childrey added another layer to the argument that a shared consumer economy wove together Britons’ lives. Gloucestershire was a centre for the manufacture of scarlet cloth, for example, because Gloucestershire’s water was particularly suited to the chemistry of dying. Leicestershire produced the highest-quality limestone. Suffolk produced butter and cheese in great quantities, but Cheshire produced the best cheese.

Importantly, the antiquaries and naturalists also elevated folk culture, and folk knowledge. Some scholars might have despised them as superstition, but others gave the ways of the people standing within their visions of Britain. The one book Aubrey published, for example, was a collection of British folk beliefs. Lhuyd asked his correspondents to read his research questionnaire out loud to illiterate Welsh-speakers, especially miners and shepherds. He trusted that their knowledge of the landscape, of the mountains and the mines, was superior to that of most gentlemen.

Many nation-building antiquaries and naturalists looked to nature, economics and archaeology in order to lead Britons away from political and religious conflict. Of course, none of them was impartial. Lhuyd, the son of a Welsh gentleman, campaigned fiercely for a Britishness that honoured the Celtic, and especially the Welsh, element. The English Camden praised the Scots while despising the Irish. Childrey skimped on coverage of the former while ignoring the latter.

Even insofar as the gentlemen antiquaries could deal impartially across England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, they could accomplish only so much. When Lhuyd crawled back out of the barrow, blinking his eyes in the drizzly Irish daylight, he walked on through a landscape scarred by battle, overlaid with movements and migrations, ancient and recent, forced and peaceable. Just 10 years earlier, the armies of the Roman Catholic King James II and the Protestant William III faced off across the Boyne River, not far from Drogheda. English elites, unwilling to risk Britain’s return to Roman Catholicism, had invited William, a Dutch military leader, into their country to help them chase out James. William won the Battle of the Boyne, but James’s heirs regularly invaded Britain via Scotland through the mid-18th century, seeking to reclaim their throne.

Forty years before James II and William III’s armies faced off along the Boyne, the Protestant revolutionary Oliver Cromwell brought his army to Ireland. They besieged the Royalist garrison at Drogheda, breaking through its six-foot-thick walls in a day. No quarter was given. Many of the dead were English soldiers, but reports circulated that Cromwell’s army indiscriminately murdered men, women and children. To this day, Drogheda is an Irish Catholic byword for English atrocities. Lhuyd walked on bloody ground. As much as he might have wished it, religious and political zeal were not things of the past.