Recently, I found myself at London Stansted Airport, travelling back to the United States. I’m a frequent flyer, so I’m familiar with the airport ritual: shoes, laptop, body scanner. But for myself and many others, the final instalment of this liturgy tends to become a social test. As usual, I braced myself and stepped into the scanner.

‘Arms like this… Anything in your pockets? Stand still.’ As the security agent stepped back to the controller, she looked up. Gender panic rose in her face. Her eyes desperately tried to undress me: female or male? Pink or blue button? (Yes, pink or blue.) ‘Female,’ I sighed, but the Plexiglas muffled my voice. ‘Female!’ I yelled. ‘The pink button!’ Other travellers froze, expecting a scene, but the agent’s face lit up. ‘I thought you were a woman!’ she announced triumphantly. She jabbed the button featuring a pink stick figure: vagina; female; woman.

As someone who is gender nonbinary, I’ve gathered hundreds of these stories. Some are funny, others vicious. Despite a widespread assumption that everyone fits into neat gender categories, I’ve always been treated as a gender question mark. My social interactions since childhood have been filled with wildly vacillating gender expectations. These days, though, I identify as nonbinary not because I am androgynous. Rather, I do so because experiencing life as an androgynous person has made me acutely aware of how gendered expectations and assumptions saturate our lives.

Unreflective critics like to accuse people like me of being ‘obsessed’ with gender. But far from being obsessed, many of us are just plain tired of it. I am tired of living in a society where everyone forces each other into a blue or a pink box. The ferocity with which these gender boxes are maintained – and the Hail Mary attempts to justify them with science – is truly staggering. Anyone who dares to challenge these boxes is met with distortion and ridicule. I don’t want to put up with it any longer: my identity is a petition for an escape hatch.

Most people assume that gender is tied to biological sex. For the majority, this means that gender is identical to sex, where sex is taken to be determined by one’s reproductive features. Call this the ‘identity’ view of gender. For others, following Simone de Beauvoir, gender is the social meaning of sex. Call this the ‘social position’ view of gender.

On either the identity or the social-position view, your gender is constrained by whether your body is sexed as male or as female. According to the identity view, your gender just is your sexed body. And, according to the social view, your gender is unavoidably indexed to your sexed body, because society imposes social roles onto you on the basis of your biology. On either view, then, it would seem that nonbinary genders do not – cannot – exist. But this is mistaken.

Consider first those who hold to a strict identity relation between gender and sex. On this view, nonbinary gender cannot exist because – it is assumed – everyone has either a male or a female body. This view proliferates on countless blogs, forums and news sources, where one finds wildly distorted discussions of what it means to be nonbinary. Nearly all conclude that nonbinary gender is a biological impossibility. The more vitriolic commenters add to this that anyone who says they are nonbinary is deranged.

It seems, then, that when I say: ‘I am nonbinary’, a staggering number of people take this to mean: ‘I don’t have female or male reproductive features’, and so dismiss my claim as absurd. But this is a conversational failure. Maybe even a bald-faced lie. We are nowhere near the end of militant insistence that nonbinary genders are a ‘biological’ impossibility. But the insistence is a façade hiding a bad argument. Let’s take the reasoning at face value:

Premise 1: Someone’s gender is identical to their set of reproductive features.

Premise 2: There are only two possible sets of reproductive features.

Conclusion: So it is impossible for someone to have a nonbinary gender.

An initial thing to notice is that the second premise is demonstrably false. The science journalist Claire Ainsworth, writing for the journal Nature in 2015, points out that this ‘simple scenario’ is distant from reality:

According to the simple scenario, the presence or absence of a Y chromosome is what counts: with it, you are male, and without it, you are female. But doctors have long known that some people straddle the boundary – their sex chromosomes say one thing, but their gonads (ovaries or testes) or sexual anatomy say another … What’s more, new technologies in DNA sequencing and cell biology are revealing that almost everyone is, to varying degrees, a patchwork of genetically distinct cells, some with a sex that might not match that of the rest of their body.

In other words, it’s uncontroversial among doctors, biologists and geneticists that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find a line in nature that cleanly divides people into males and females. So, even granting the first premise, the argument fails: reproductive features do not neatly fall into binary categories. The biological world is far messier than XX and XY chromosomes.

Making this point and walking away would be hasty. True, intersex people – those whose biological features combine male- and female-coded reproductive features – exist. But it doesn’t further our understanding of nonbinary identities, because having an intersex condition is neither sufficient nor necessary for being nonbinary. The majority of nonbinary individuals do not have an intersex condition, nor do they take themselves to.

Having feet is correlated with walking, but I can walk on my hands if I want to

The argument is meant to conclude that nonbinary genders – not intersex conditions – are impossible. But if it indeed does, a vital error surfaces within the argument. The term ‘gender’, as it is used in the first premise, refers to sets of reproductive features. But the term ‘gender’, as it is used in the conclusion, must refer to social identifications and not biological classifications. In short, the argument equivocates, and so fails.

Many discussions about nonbinary identities suffer from a lack of basic terminological agreement. Without it, we are engaged in what philosophers call metalinguistic negotiation: an argument over what a word should mean, and not an argument about what the world is like. Suppose the US Vice President Mike Pence tells me, after the legal success of marriage equality in the United States, that: ‘I believe marriage is only between a man and a woman.’ I respond by brushing him off as delusional: ‘Just because you say something about the law doesn’t make it so!’ Anyone paying attention would identify my response as missing the mark. Clearly, whatever Pence means by the word ‘marriage’ – something based on certain Biblical precepts, no doubt – is not what I mean by it.

Similarly, even a brief glance inside the communities that developed and regularly use terms such as ‘nonbinary’, ‘agender’, ‘genderqueer’ and so on reveals that these terms certainly don’t mean something about one’s reproductive features. Consider just one example, borrowed from a 2017 qualitative study of transgender (increasingly known simply as ‘trans’) individuals:

‘My gender changes. Sometimes I am female, sometimes I am a boy, sometimes I am both, and sometimes I am neither.’

If we substitute ‘have a vagina’ for ‘am female’, and ‘have a penis’ for ‘am a boy’, the result is nonsensical. Yet for the doubters’ argument to be valid, it would need to be the case that ‘gender’ must refer to one’s set of reproductive features. The main problem with this suggestion – other than violating any plausible theory of semantics – is that no one believes it. For all the huffing about how gender is just body parts, no one in practice holds the identity view of gender. If gender is just reproductive features and nothing more, it makes no more sense to insist that people must look, love or act in particular ways on the basis of gender than it would to demand that people modify their behaviour on the basis of eye colour or height.

Even if reproductive traits are correlated to personality, physical capabilities or social interests, such correlations don’t equate to norms. As David Hume has taught us, is doesn’t make ought. Having feet is correlated with walking, but I can walk on my hands if I want to. Having a tongue is correlated with experiencing taste, but who cares if I decide to drink Soylent every day? Once we recognise that gender categories mark how one ought to be, and not only how one’s body is, the identity view unravels. To build in the ‘oughts’ is to admit that gender is more than just body parts.

The idea that gender is more than body parts is old news to feminists. A distinction between sex and gender, in which genders are the social positions forced upon certain sexed bodies, has long circulated among feminist theorists and activists. And, no doubt, this way of thinking about gender has helped to debunk ideas about how female persons ‘naturally’ should be and reveal widespread social discriminations against these persons.

But while the social-position view distinguishes between bodily features and gender, and takes gender to be a fundamentally social phenomenon, this view still welds gender to assigned sex. For example, on this theory, someone is a woman if they are (or were from birth) socially marked as female. And, since many nonbinary persons are (and were) marked as male or female, they are in fact men or women on the social-position view. They do not have a nonbinary gender.

Here we run again into linguistic mismatch: most nonbinary persons do not claim they are (or were) not marked with a binary sex, or socialised according to that assigned sex. Whatever these persons mean by claiming nonbinary identities, it is not a lack of gendered socialisation. So what does it mean to be nonbinary then?

To see gendered reality, be a Tiresias, throbbing between overlapping but radically segregated worlds

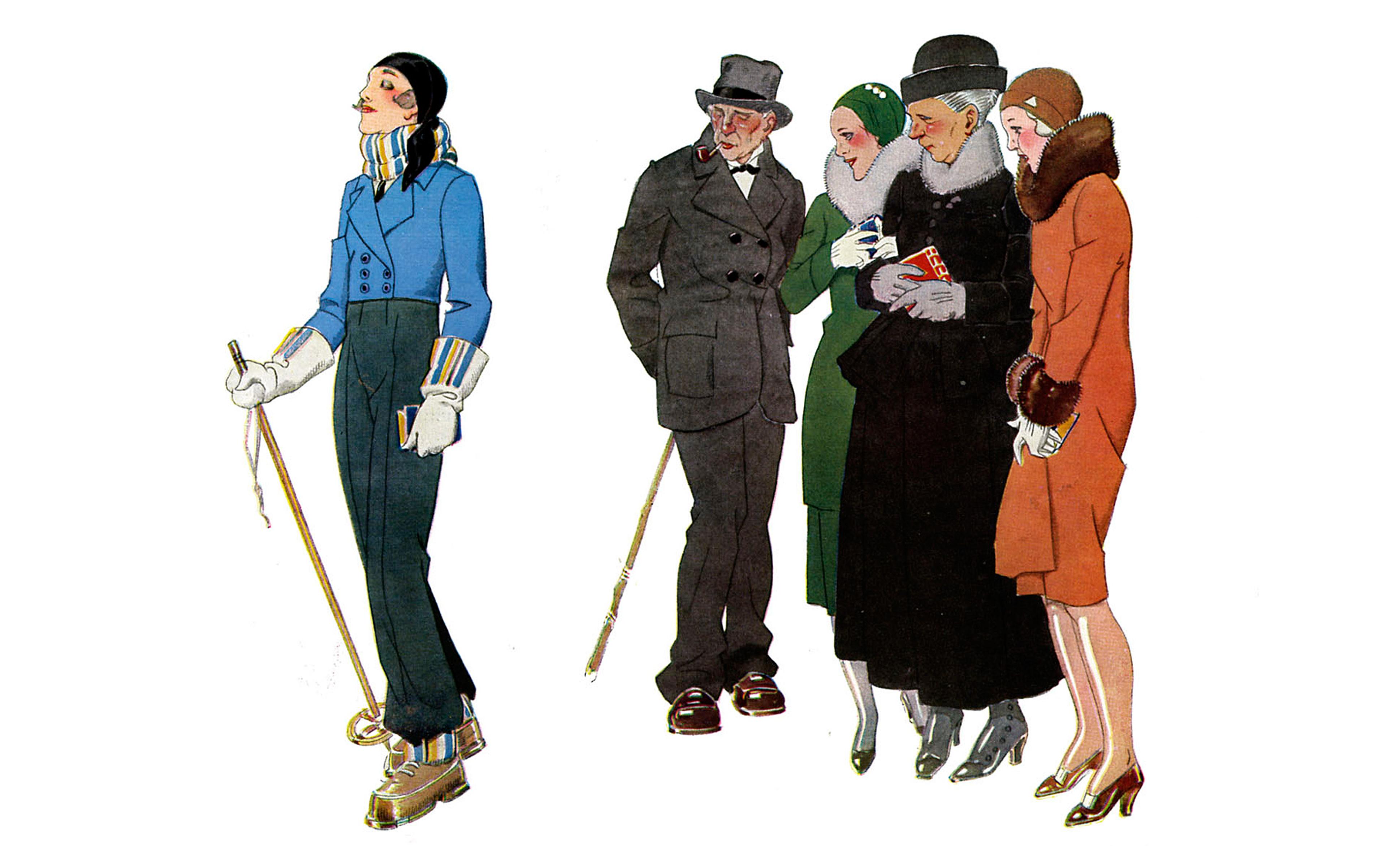

One popular idea is that being nonbinary simply means being gender-nonconforming, or being androgynous. Terms such as ‘androgynous’, ‘gender fluid’ and ‘nonbinary’ are often used interchangeably in marketing campaigns and social media. But this won’t do either: many nonbinary persons are not androgynous, and many androgynous persons would not claim nonbinary identities. True, nonbinary persons are often androgynous. But, in many cases, androgyny simply is the catalyst for realising how thoroughly arbitrary and suffocating gender is: it cannot remain invisible to someone whose ability to fit within its structures is perpetually scrutinised.

Take what happened to me a few months ago. I came out of a women’s restroom to find a very angry man and (I presume) his girlfriend. ‘What the fuck were you doing in the women’s bathroom?’ he yelled in my face. ‘I should beat the shit out of you.’ I’m not sure what I said, but I replied, with my female-coded voice. His demeanour shifted completely. He stammered: ‘I thought… You look…’ Then he ran away.

Such experiences have taught me – even if in a muted sense – how much our perceived gender constrains how we move through the world. In his poem The Waste Land (1922), T S Eliot was right to describe Tiresias, a mythological prophet who was transformed into a woman, as someone who ‘though blind … can see’. The best way to see gendered reality is to be a Tiresias, throbbing between overlapping but radically segregated worlds. Some prefer to live in those worlds: nonbinary persons seek an alternative.

I consider nonbinary identity to be an unabashedly political identity. It is for anyone who wishes to wield self-understanding in service of dismantling a mandatory, self-reproducing gender system that strictly controls what we can do and be. As the philosopher Kate Manne puts it in her book Down Girl (2017), this system rewards and valorises those who conform to binary gender expectations, and punishes and polices those who do not. To be nonbinary is to set one’s existence in opposition to this system at its conceptual core.

As a result, nonbinary identity cannot be based on having androgynous reproductive features or aesthetic expression. Androgyny itself is defined with reference to binary gender concepts. But gendered conformity – even conformity to nonconformity – cannot be a requirement of nonbinary identity. It cannot be defined in a way that upholds the very concepts it seeks to unravel. Unlike womanhood or manhood, nonbinary identity is open to anyone and forced upon no one. It is radically anti-essentialist. It is opt-in only.

‘I don’t want to be a girl wearing boy’s clothes, nor do I want to be a girl who presents as a boy,’ said the nonbinary teenager Kelsey Beckham in an interview with The Washington Post in 2014. ‘I’m just a person wearing people clothes (my emphasis).’ Beckham’s claim gets at the heart of nonbinary identity. Beckham does not deny that they have female- or male-coded sex characteristics. They do not deny having a gendered social position. They do not insist that they have an androgynous aesthetic. In my view, Beckham’s claim is best interpreted as a challenge: Why do you insist on perceiving me through binary gender concepts? Their statement illuminates, if only for a moment, our constant and unthinking habit of using binary gender categories as a lens through which to view and evaluate nearly everything about a person – their relationships, occupation, clothes, heights, athletic ability, intelligence, personality, and on and on, ad nauseum.

What justifies this habit? Why do we continue to do it? Nonbinary individuals, by refusing to comply with binary categories, raise these questions and – with their very existence – refuse to put them down. While other feminisms question the unequal value placed on femininity and masculinity, highlighting the resulting gender inequalities, the nonbinary movement questions why we insist on these categories at all.

Some prefer to make these categories gooey on the inside; I prefer to torch them

To reduce the world to pink and blue buttons, we’ve relied on an ability to designate and maintain rigid groupings of physical features, aesthetic expressions, sexualities, personalities and social dispositions. These groupings are maintained by normed conformity: anyone who fails to conform should conform on pain of being ‘gender trash’, to borrow a term from the activist Riki Wilchins. A slew of terms existed to denigrate those who are gender trash: ‘dyke’, ‘fairy’, ‘tranny’, ‘sissy’, ‘queer’. In reclaiming these and other terms, people have started to embrace being gender trash. Nonbinary individuals go a step further: they challenge the categories that allow persons to be marked as gender trash in the first place.

Policing masculinity and femininity requires that there be men and women. Challenging these categories, in part by revealing the false but pervasive assumption that everyone fits within them, threatens those who wish to preserve social control over sexed bodies – especially control that systematically favours males who conform to dominant masculine norms. If people embrace an ontological space outside the gender binary, it undermines this ideology. Its perpetuation relies on the myth that gender – understood as sets of reproductive features that make us apt for certain social roles – is binary, universal and natural. Claims to nonbinary gender, unlike the social-position view of gender, open up a fissure between reproductive features and social possibility. They question the ontological basis of gender as well as its political justification.

None of this is to deny the many means of gender resistance within the binary. It is powerful to insist that women and men should be able to look, act and simply be any way they want. Countless people identify as men or women while simultaneously bucking gender norms. For many of them, being understood as a man or a woman is important for describing how they were socialised as children, how others interpret their bodies, or how they feel about their own bodies. This is wonderful: the more sledgehammers we take to gender categories, the better. Some prefer to make these categories gooey on the inside; I prefer to torch them. There’s enough room for all at the barbecue.

Rather than insist that men and women can be and can do anything, I and other nonbinary persons question why we categorise people as women and men at all. Questions about what categories should guide our social lives cannot be answered by simply describing the world, because they ask how we should describe the world. They are inherently normative questions. Philosophers have long discussed reasons why some categories are better to use than others. In the sciences, for example, it seems clear that considerations of simplicity and explanatory power are significant when determining how best to categorise reality. Nonbinary identities force us to place binary gender categories under similar scrutiny, but with greater attention to moral and political considerations. We must ask not only what these categories are, but also why and whether we should continue to use them.

Are we nearing the end of gender as we know it? As it has been imposed upon us since birth? On more optimistic days, especially after interacting with my students, I feel hopeful. At other times, I read that the US Department of Justice is dismantling trans rights by ordering that workplace discrimination laws do not apply to discrimination based on gender identity. Or that the Trump administration is attempting to legally erase trans persons’ existence by defining gender based on a person’s genitalia at birth. Or that Ciara Minaj Frazier, a 31-year-old black trans woman, has become the 22nd trans person known to have been murdered in the US in 2018 alone. On these days, I’m not as sure.

What I do know is that our gender systems are not only broken, but that they never worked. For binary and nonbinary folks alike, they damage mental and physical health, promote economic inequality, and fuel sexual and other gendered violence. For my gender trash kin, and especially persons of colour, they make life into a tightrope where one misstep or just bad luck ends in unemployment, harassment, rape, beatings or even death. We must continue to question a culture that mandates infants’ genitals be coded according to a binary that determines much of their lives. ‘Gender obsessed’ indeed.